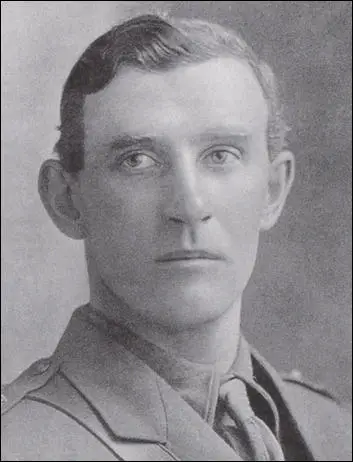

Raymond Asquith

Raymond Asquith, the eldest of the five children of H. H. Asquith and his first wife, Helen Melland, was born in Hampstead on 6th November 1878. His father was a lawyer but In the 1886 General Election he was elected as the Liberal MP for East Fife. (1)

Helen also gave birth to Herbert (1881), Arthur (1883), Violet (1887) and Cyril (1890). The couple were devoted to their children. Herbert pointed out that both his parents "allowed their children a full measure of liberty; they used the snaffle rather than the curb and their control was very elastic in nature." (2)

In the summer of 1891 the Asquiths had a holiday on the Isle of Arran. On 20th August, their son, Herbert, became feverish and his mother moved in to his room to nurse him. The following day she was taken ill. A doctor was called and he diagnosed typhoid and she died on 11th September. Herbert Henry Asquith wrote that night: "She died at nine this morning. So end twenty years of love and fourteen of unclouded union. I was not worthy of it, and God has taken her. Pray for me." (3)

In the 1892 General Election held in July, Gladstone's Liberal Party won the most seats (272) but he did not have an overall majority and the opposition was divided into three groups: Conservatives (268), Irish Nationalists (85) and Liberal Unionists (77). Robert Cecil, 3rd Marquis of Salisbury, refused to resign on hearing the election results and waited to be defeated in a vote of no confidence on 11th August. Gladstone, now 84 years old, formed a minority government dependent on Irish Nationalist support. H. H. Asquith was appointed as Gladstone's Home Secretary. (4)

H. H. Asquith married Margot Tennant on 10th May 1894. She wrote to Raymond about her new role as stepmother: "You must not think that I could imagine even a possibility of filling your mother's (and my friend's) place. I only ask you to let me be your companion - and if needs be your help-mate. There is room for everyone in life if they have the power to love. I shall count upon your help in making my way with Violet and your brothers... I should like you to let me gradually and without effort take my place among you, and if I cannot - as indeed I would not - take your mother's place among you, you must at least allow me to share with you her beautiful memory." (5)

Education of Raymond Asquith

Academically gifted, he was educated at at Winchester College (1892–7) and at Balliol College (1897–1902), winning scholarships at both institutions. As well as being president of the Oxford Union (1900), he won the chief university prizes, including the Ireland, Craven, and Derby scholarships, and took first-class honours in classics and law. (6)

It has been argued: "He (Raymond) was intellectually one of the most distinguished young men of his day and beautiful to look at, added to which he was light in hand, brilliant in answer and interested in affairs. When he went to Balliol he cultivated a kind of cynicism which was an endless source of delight to the young people around him; in a good-humoured way he made a butt of God and smiled at man. If he had been really keen about any one thing - law or literature - he would have made the world ring with his name, but he lacked temperament and a certain sort of imagination and was without ambition of any kind. In spite of this record, a more modest fellow about his own achievements never lived." (7)

According to one of his fellow students, John Buchan, Asquith was one of those men "whose brilliance in boyhood and early manhood dazzles their contemporaries and becomes a legend". (8) Winston Churchill wrote: "He was a character of singular charm and distinction - so gifted and yet so devoid of personal ambition, so critically detached from ordinary affairs yet capable of the utmost willing sacrifice". (9) The idea that he was cynical was rejected by his friend, Hugh Godley: "There never was a more absurd idea than that Raymond was cynical or unfeeling, he was most tenderhearted and affectionate. But no one was ever more shy about his enthusiasms." (10)

In 1904 Asquith was called to the bar at the Inner Temple. It has been pointed out that like his father "he had a low tolerance for the dull work required of juniors and little professional ambition". Asquith married Katharine Frances Horner (1885–1976) on 25th July, 1907. John Jolliffe has pointed out: "Asquith's outstandingly happy marriage brought to light his capacity for deep feeling and personal commitment, always present in his character but which he concealed in youth, giving rise at times to a mistaken impression of cynicism." (11)

Henry Campbell-Bannerman suffered a severe stroke in November, 1907. He returned to work following two months rest but it soon became clear that the 71 year-old prime minister was unable to continue. On 27th March, 1908, he asked to see Asquith. According to Margot Asquith: "Henry came into my room at 7.30 p.m. and told me that Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman had sent for him that day to tell him that he was dying... He began by telling him the text he had chosen out of the Psalms to put on his grave, and the manner of his funeral... Henry was deeply moved when he went on to tell me that Campbell-Bannerman had thanked him for being a wonderful colleague." (12)

Campbell-Bannerman suggested to Edward VII that Asquith should replace him as Prime Minister. However, the King with characteristic selfishness was reluctant to break his holiday in Biarritz and ordered him to continue. On 1st April, the dying Campbell-Bannerman, sent a letter to the King seeking his permission to give up office. He agreed as long as Asquith was willing to travel to France to "kiss hands". Colin Clifford has argued that "Campbell-Bannerman... for all his defects, was probably the most decent man ever to hold the office of Prime Minister. Childless and a widower since the death of his beloved wife the year before, he was now facing death bravely, with no family to comfort him." Campbell-Bannerman died later that month. (13)

Raymond agreed with his father's political philosophy and in 1913 he was adopted as Liberal Party candidate for Derby, where the sitting member was retiring. John Buchan thought he would be a great success as a politician: "He had every advantage in the business - voice, language, manner, orderly thought, perfect nerve and coolness... Though he might scoff at most dogmas, he had a great reverence for the problems behind them, and to these problems he brought a fresh mind and a sincere goodwill." His brother, Herbert Asquith, commented "he was a brilliant speaker, and if he had entered the House, there is little doubt that he would have made his presence felt." (14)

First World War

On 7th August, 1914, the House of Commons was told that Britain needed an army of 500,000 men. The same day Lord Kitchener, the new Secretary of State for War,issued his first appeal for 100,000 volunteers. He got an immediate response with 175,000 men volunteering in a single week. With the help of a war poster that featured Kitchener, and the words: "Join Your Country's Army".

Raymond's three brothers, Cyril (24), Arthur (31) and Herbert (33) immediately joined the armed forces. Herbert pointed out "England expects every man to do his duty" and if they did not offer their services "Father will be asked why he doesn't begin his recruiting at home". Arthur agreed and was the first to join: "I have two older brothers, both married, and one younger brother with an ailing colon... It is obviously fitting that one of my father's four sons ought to be prepared to fight". (15)

Raymond Asquith, was nearly 36 and was married with two young children, Helen and Perdita. A third child, Julian would be born soon afterwards. He was less enthusiastic about the war than his younger brothers. Raymond was on the left of the Liberal Party and had doubts about the wisdom of declaring war on Germany. He had no confidence in Lord Kitchener, who he described as the "King of Chaos" and expected the war to last at least three years and predicted that "sooner or later they (his brothers) would all be under the turf". (16)

Arthur Asquith was the first to see action in the 2nd Royal Naval Division, a collection of naval reservists that became known as the Anson Battalion that had been formed by Winston Churchill. A fellow officer was his friend Rupert Brooke. On 8th October, 1914, the battalion attempted to take the port of Antwerp, from the German Army. This ended in failure and they were forced to escape back to England.

Asquith later wrote to Venetia Stanley about what happened: "I can't tell you what I feel of the wicked folly of it all. The Marines of course are splendid troops and can go anywhere and do anything: but nothing excuses Winston Churchill (who knew all the facts)... I was assured that all the recruits were being left behind, and that the main body at any rate consisted of seasoned Naval Reserve men. As a matter of fact only about a quarter were Reservists, and the rest were a callow crowd of the rawest tiros, most of whom had never fired off a rifle, while none of them had ever handled an entrenching tool." (17)

Herbert Asquith was also sent to Belgium and saw action at Nieuwpoort. He later recalled: "The ground was scattered with large numbers of the dead, French and German, lying on that powdered and shell-pitted soil, on their faces or their backs, tangled on the barbs of the rusted wire, or tossed over the brink of a shell-hole, and here and there a rigid arm stretched upwards aimlessly to the sky." (18)

The Western Front

Despite his doubts about the war, Raymond Asquith joined the Queen's Westminster Rifles in January 1915. "As the months went by with no sign of the regiment being sent abroad, Raymond... became increasingly frustrated with such futile tasks as stopping suspicious vehicles approaching London from the North-West." His wife, afraid that he would seek to serve abroad, tried to convince him to stand as a Liberal Party candidate in a by-election, but he rejected the idea as he saw it as an act of cowardice. (19)

His friend, Hugh Godley, later wrote: "Raymond was so absolutely unmilitary and when the war came, he went into it not with any burning enthusiasm, but just as a sort of matter of course, and he went on with his soldiering just as he went on with his own profession before, in the conscientious methodical way which was so characteristic of him... fully realizing what the end might be, but never to all appearances in the least conscious of it." (19a)

Aware that he would not see active service in this regiment he transferred as a lieutenant into the 3rd battalion of the Grenadier Guards and went out to the Western Front in October, 1915. Margot Asquith wrote: "Raymond left this morning... I was almost surprised at how sad I felt at parting with him - there was something so pathetic and incongruous in seeing so perfect and highly finished a being going off into that raw brutal primitive hurly-burly." (20)

H. H. Asquith was furious with his son and refused to write to him while he was on the Western Front. However, he was posted to one of the comparatively quiet sections of the front line, where shelling was sporadic. He wrote to his friend, Diana Manners, that he was more concerned by the discomfort than the danger, complaining about "being up to his neck in dense, sticky blue clay; at the same time he was puzzled that while the sound of rifle fire seemed no more far off than the next gun in a partridge drive". (21)

In an early letter to his wife from the front he complained about the lack of dry trenches and the failures of the authorities in making no adequate preparations for winter, claiming that half of his men did not have trench boots. He also noted the contempt felt for staff officers behind the lines by those in the trenches, and felt that she would think he was right not to become one, "though of course one may find in the end that there are more uncomfortable things than general abuse". (22)

Asquith was very unimpressed with the training for creeping barrage that took place before the attack on the German front-line trenches. Colin Clifford has commented: "He had been up since five o'clock participating in an exercise designed to simulate an attack on enemy trenches behind a creeping barrage, the recently devised tactic of laying down a steadily moving curtain of shell fire some fifty yards in front of the infantry as they advanced. In the exercise the barrage was simulated by drummers, allowing him to give full rein to his sense of the ridiculous. To him the sight of four battalions walking in lines at a funeral pace across cornfields preceded by a row of drummers was more like some ridiculous religious ritual ceremony performed by a Maori tribe, than a brigade of Guards training for battle." (22a)

On the Western Front in December 1914 there was a spontaneous outburst of hostility towards the killing. On 24th December, arrangements were made between the two sides to go into No Mans Land to collect the dead. Negotiations also began to arrange a cease-fire for Christmas Day. On other parts of the front-line, German soldiers initiated a cease-fire through song. On Christmas Day the guns were silent and there were several examples of soldiers leaving their trenches and exchanging gifts. The men even played a game of football. (23)

In January 1916, Asquith was asked to work as defence counsel to Ian Colquhoun who was being court-martialled for "allowing his men to fraternise with the Germans on Christmas Day". Raymond was impressed by Colquhoun "for the vigour and nerve with which he faced his accusers" and in his "insolence, aplomb, courage and elegant virility". Despite his efforts, Colquhoun was convicted but escaped with a reprimand. (24)

Raymond Asquith resisted attempts by his father to use his influence to transfer him onto the General Staff but against his wishes he did serve for four months (January to May 1916) at general headquarters of the British Expeditionary Force, at Saint-Omer, where he "served unenthusiastically in intelligence work". (25)

During this period he became greatly concerned about the influence of Lord Northcliffe and his newspapers, The Times and The Daily Mail. There were constant criticism of Asquith, especially over the reluctance of accepting the need of conscription (compulsory enrollment). "Raymond was an indignant as anyone, telling Katherine Asquith that he had reached the stage when he would rather defeat Northcliffe than defeat the Germans. The press lord seemed to him just as belligerently crass and crassly belligerent as the enemy were, but far less courageous and capable". (26)

Death at Lesboeufs

Raymond Asquith returned to the Western Front on 16th May 1916. He became increasingly critical of the way the war was being fought. He told his wife that "almost every night there were raids on the German lines accompanied by the usual ridiculous artillery barrage" and he "considered the whole business to be a charade, usually causing far more British than German casualties". (27)

On 7th September, 1916, H. H. Asquith visited the front-line and managed to obtain a meeting with his son. He wrote to Margot Asquith that evening: "He was very well and in good spirits. Our guns were firing all round and just as we were walking to the top of the little hill to visit the wonderful dug-out, a German shell came whizzing over our heads and fell a little way beyond... We went in all haste to the dug-out - 3 storeys underground with ventilating pipes electric light and all sorts of conveniences, made by the Germans. Here we found Generals Horne and Walls (who have done the lion's share of all the fighting): also Bongie's brother who is on Walls's staff. They were rather disturbed about the shell, as the Germans rarely pay them such attention, and told us to stay with them underground for a time. One or two more shells came, but no harm was done. The two generals are splendid fellows and we had a very interesting time with them." (28)

On 15th September, Raymond Asquith led his men on a attack on the German trenches at Lesboeufs. According to one of his men "such coolness under shell fire as he displayed would be difficult to equal". Soon after leaving the trench he was hit in the chest by a bullet. Raymond knew straightaway that his wound was fatal, but in order to reassure his men, he casually lit a cigarette as he was carried on a stretcher to the dressing station. A medical orderly wrote to his father to say he was not given morphia "as he was quite free from pain and just dying." (29)

Raymond Asquith died on the way to the dressing station. According to a soldier quoted by John Jolliffe: "There is not one of us who would not have changed places with him if we had thought that he would have lived, for he was one of the finest men who ever wore the King's uniform, and he did not know what fear was." Only five of the twenty-two officers in Asquith's battalion survived the battle unscathed. (30)

When his father was informed of his death "he put his head on his arms on the table and sobbed passionately". He told Margot Asquith: "The awful waste of a man like Raymond - the best brain of his age in our time - any career he liked lying in front of him. I always felt it would happen." Two days later he wrote to Sylvia Henley: "I can honestly say, that in my own life he was the thing of which I was truly proud, and in him and his future I had invested all my stock of hope." (31)

On 22nd September, 1916, Raymond's sister, Violet Bonham Carter, wrote: "He was shot through the chest and carried back to a shell-hole where there was an improvised dressing station. There they gave him morphia and he died an hour later. God bless him. How he has vindicated himself - before all those who thought him merely a scoffer - by the modest heroism with which he chose the simplest and most dangerous form of service - and having so much to keep for England gave it all to her with his life." (32)

Winston Churchill added: "It seemed quite easy for Raymond Asquith, when the time came, to face death and to die.... The War which found the measure of so many, never got to the bottom of him, and when the Grenadiers strode into the crash and thunder of the Somme, he went to his fate cool, poised, resolute, matter of fact, debonair. And well we know that his father, then bearing the supreme burden of the State, would proudly have marched at his side." (33)

Primary Sources

(1) Margot Asquith, letter to Raymond Asquith (14th February, 1894)

You must not think that I could imagine even a possibility of filling your mother's (and my friend's) place. I only ask you to let me be your companion - and if needs be your help-mate. There is room for everyone in life if they have the power to love. I shall count upon your help in making my way with Violet and your brothers... I should like you to let me gradually and without effort take my place among you, and if I cannot - as indeed I would not - take your mother's place among you, you must at least allow me to share with you her beautiful memory.

(2) Colin Clifford, The Asquiths (2002)

The truth was that Raymond never much liked London society. He confessed to Aubrey Herbert that there were half a dozen women and perhaps a dozen men whose company he enjoyed, but he found intolerable the myriad of insincere conventions and pompous restrictions with which one had to contend, to say nothing of twittering women and vacuous men. He was no more enamoured of the Bar. Writing from his dingy chambers whose windows were encrusted with pigeon droppings, he described his fellow lawyers as hundreds of tedious men, as like real men as a pianola was to a piano, reading dust-covered books reeking of decay, which were as like real books as a beetle was to a butterfly.

(3) Margot Asquith, Autobiography (1920)

He (Raymond) was intellectually one of the most distinguished young men of his day and beautiful to look at, added to which he was light in hand, brilliant in answer and interested in affairs. When he went to Balliol he cultivated a kind of cynicism which was an endless source of delight to the young people around him; in a good-humoured way he made a butt of God and smiled at man. If he had been really keen about any one thing - law or literature - he would have made the world ring with his name, but he lacked temperament and a certain sort of imagination and was without ambition of any kind. In spite of this record, a more modest fellow about his own achievements never lived.

(4) Colin Clifford, The Asquiths (2002)

He (Raymond Asquith) had been up since five o'clock participating in an exercise designed to simulate an attack on enemy trenches behind a creeping barrage, the recently devised tactic of laying down a steadily moving curtain of shell fire some fifty yards in front of the infantry as they advanced. In the exercise the barrage was simulated by drummers, allowing him to give full rein to his sense of the ridiculous. To him the sight of four battalions walking in lines at a funeral pace across cornfields preceded by a row of drummers was more like some ridiculous religious ritual ceremony performed by a Maori tribe, than a brigade of Guards training for battle.

(5) Herbert Henry Asquith, letter to Margot Asquith (7th September, 1916)

He was very well and in good spirits. Our guns were firing all round and just as we were walking to the top of the little hill to visit the wonderful dug-out, a German shell came whizzing over our heads and fell a little way beyond ... We went in all haste to the dug-out - 3 storeys underground with ventilating pipes electric light and all sorts of conveniences, made by the Germans. Here we found Generals Horne and Walls (who have done the lion's share of all the fighting): also Bongie's brother who is on Walls's staff. They were rather disturbed about the shell, as the Germans rarely pay them such attention, and told us to stay with them underground for a time. One or two more shells came, but no harm was done. The two generals are splendid fellows and we had a very interesting time with them.

(6) Violet Bonham Carter, letter to Hugh Godley (22nd September, 1916)

He was shot through the chest and carried back to a shell-hole where there was an improvised dressing station. There they gave him morphia and he died an hour later. God bless him. How he has vindicated himself - before all those who thought him merely a scoffer - by the modest heroism with which he chose the simplest and most dangerous form of service - and having so much to keep for England gave it all to her with his life.

(7) Margot Asquith, Autobiography (1920)

On Sunday, September the 17th, we were entertaining a weekend party, which included General and Florry Bridges, Lady Tree, Nan Tennant, Bogie Harris, Arnold Ward, and Sir John Cowans. While we were playing tennis in the afternoon my husband went for a drive with my cousin, Nan Tennant. He looked well, and had been delighted with his visit to the front and all he saw of the improvement in our organization there: the tanks and the troops as well as the guns. Our Offensive for the time being was going amazingly well. The French were fighting magnificently, the House of Commons was shut, the Cabinet more united, and from what we heard on good authority the Germans more discouraged. Henry told us about Raymond, whom he had seen as recently as the 6th at Fricourt.

As it was my little son's last Sunday before going back to Winchester I told him he might run across from the Barn in his pyjamas after dinner and sit with us while the men were in the dining-room.

While we were playing games Clouder, our servant - of whom Elizabeth said, "He makes perfect ladies of us all" - came in to say that I was wanted.

I left the room, and the moment I took up the telephone I said to myself, "Raymond is killed".

With the receiver in my hand, I asked what it was, and if the news was bad.

Our secretary, Davies, answered, "Terrible, terrible news. Raymond was shot dead on the 15th. Haig writes full of sympathy, but no details. The Guards were in and he was shot leading his men the moment he had gone over the parapet."

I put back the receiver and sat down. I heard Elizabeth's delicious laugh, and a hum of talk and smell of cigars came down the passage from the dining-room.

I went back into the sitting-room.

"Raymond is dead," I said, "he was shot leading his men over the top on Friday."

Puffin got up from his game and hanging his head took my hand; Elizabeth burst into tears, for though she had not seen Raymond since her return from Munich she was devoted to him. Maud Tree and Florry Bridges suggested I should put off telling Henry the terrible news as he was happy.

I walked away with the two children and rang the bell:

"Tell the Prime Minister to come and speak to me", I said to the servant.

Leaving the children, I paused at the end of the dining-room passage; Henry opened the door and we stood facing each other.

He saw my thin, wet face, and while he put his arm round me I said: "Terrible, terrible news."

At this he stopped me and said: "I know... I've known it.... Raymond is dead."

He put his hands over his face and we walked into an empty room and sat down in silence.

(8) Winston Churchill, Nash's Magazine (August, 1928)

It seemed quite easy for Raymond Asquith, when the time came, to face death and to die. When I saw him at the Front he seemed to move through the cold, squalor and peril of the winter trenches as if he were above and immune from the common ills of the flesh, a being clad in polished armour, entirely undisturbed, presumably invulnerable. The War which found the measure of so many, never got to the bottom of him, and when the Grenadiers strode into the crash and thunder of the Somme, he went to his fate cool, poised, resolute, matter of fact, debonair. And well we know that his father, then bearing the supreme burden of the State, would proudly have marched at his side.

Student Activities

1832 Reform Act and the House of Lords (Answer Commentary)

The Chartists (Answer Commentary)

Women and the Chartist Movement (Answer Commentary)

Benjamin Disraeli and the 1867 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

William Gladstone and the 1884 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Canal Mania (Answer Commentary)

Early Development of the Railways (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)

The Luddites: 1775-1825 (Answer Commentary)

The Plight of the Handloom Weavers (Answer Commentary)

Health Problems in Industrial Towns (Answer Commentary)

Public Health Reform in the 19th century (Answer Commentary)

Walter Tull: Britain's First Black Officer (Answer Commentary)

Football and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

Football on the Western Front (Answer Commentary)

Käthe Kollwitz: German Artist in the First World War (Answer Commentary)

American Artists and the First World War (Answer Commentary)