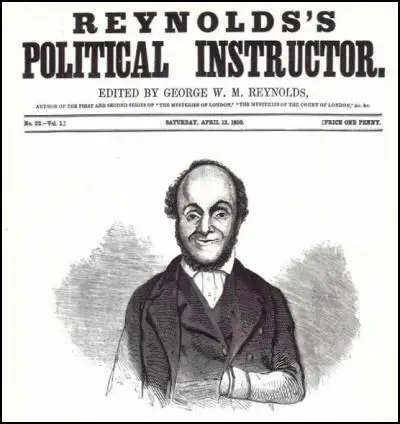

William Cuffay

William Cuffay was born in Chatham, Kent, in 1788. William's father was a naval cook and former slave. When William was old enough he found work as an apprentice tailor.

At first Cuffay held conservative views and as late as 1833 he was arguing against the formation of trade unions. Cuffay was the last member of his lodge to join the new tailors' union. However, when the tailors' union came out on strike in April 1834, Cuffay joined them and as a result lost his job. Angry about the way he had been treated and now convinced that workers needed to be represented in parliament, Cuffay became involved in the struggle for universal suffrage.

In 1839 Cuffay joined the Metropolitan Tailors' Charter Association. He became an important figure in the Chartist movement in London and in 1842 was elected to the five man national executive of the National Charter Association. Later that year he was chosen to become president of the London Chartists. Cuffay argued strongly for the Chartists to remain independent from the Anti-Corn Law League and was portrayed by newspapers as one of the leaders of the militants. The Times described the militants in London as "the black man and his party".

After 1845 Cuffay became associated with Fergus O'Connor. He supported O'Connor's Land Plan and in 1846 he was made auditor to the Land Company, a position he held for the next two years. He was now seen as the leading figure in the Physical Force Chartists in London. He was one of the three London delegates at the National Convention and was considered to be one of the most militant members. At the 1848 Kennington Common meeting he was urged by some Chartists to lead an armed uprising in London.

In the summer of 1848 a government spy called Powell provided information on a group of London Chartists. Based on the evidence acquired by Powell, Cuffay was arrested and brought before the courts. The Illustrated London News reported: "Cuffay spoke in strong language against the dispersal of the meeting and contended that it would be time enough to evince their fear of the military when they met them face to face! He believed the whole Convention were a set of cowardly humbugs, and he would have nothing more to do with them. He then left the van, and got among the crowd, where he said that O'Connor must have known all this before, and that he ought to have informed them of it, so that they might have conveyed the petition at once to the House of Commons without crossing the bridges. They had been completely caught in a trap."

Cuffay was given support by The Northern Star. On 8th October, 1848 it claimed: "The conduct of Cuffay throughout his trial was that of a man. A somewhat singular appearance, certain eccentricities of manner, and a habit of unregulated speech, afforded an opportunity to the 'suckmug' reporters, unprincipled editors, and buffoons of the press to make him the subject of their ridicule. The fast men of the press ... did their best to smother their victim beneath the weight of their heavy wit. In a great measure, Cuffay owes his destruction to the Press gang. But his manly and admirable conduct on his trial affords his enemies no opportunity either to sneer at or abuse him. His protest from first to last against the mockery of being tried a by a jury animated by class-resentments and party-hatred showed him to be a much better respecter of' the constitution than either the Attorney General or the Judges on the bench."

Cuffay was convicted and sentenced to be transported to Tasmania for 21 years. Cuffay issued a statement after his conviction: "The present Government is now supported by a regular organized system of espionage which is a disgrace to this great and boasted free country.... I say you have no right to sentence me. Although the trial has lasted a long time, it has not been a fair trial, and my request to have a fair trial - to be tried by my equals - has not been complied with. Everything has been done to raise a prejudice against me, and the press of this country - and I believe of other countries too - has done all in its power to smother me with ridicule. I ask no pity. I ask no mercy. I expected to be convicted, and I did not think anything else. No, I pity the Government, and I pity the Attorney General for convicting me by means of such base characters. The Attorney General ought to be called the Spy General. I am not anxious for martyrdom, but after what I have endured this week, I feel that I could bear any punishment proudly, even to the scaffold."

Cuffay's wife worked for Richard Cobden until she raised enough money to join her husband in 1853. Three years later all political prisoners in Tasmania were pardoned. Cuffay decided not to return to England and instead became a tailor in Tasmania. He became involved in radical politics and trade union issues and played an important role in persuading the authorities to amend the Master and Servant Law in the colony.

William Cuffay died in poverty in Tasmania's workhouse in July 1870.

Primary Sources

(1) R. G. Gammage, History of the Chartist Movement (1894)

In September, the London Chartists were brought to trial and were indicted for conspiring to levy war against Her Majesty. A number of witnesses were called, the principal being the spy and informer, Powell. Cuffay objected to being tried by a middle-class jury, and demanded, according to the provisions of Magna Charta, to be tried by the jury of his peers.

On the evidence of these villainous spies of a more villainous Government, Dowling, Cuffay, Fay and Lacey, were found guilty. On being brought up for judgment, Fay said, "It must be evident to everybody that Powell was committing perjury in all he stated. It is useless to say more." Lacey declared that he never had the slightest intention to carrying out the Charter by violence."

(2) Extract from a report Powell sent to the Police Commissioners in 1848.

I encouraged and stimulated these men, in order to inform on them. I gave the men some bullets. I gave balls to Gurney. I gave him half-a-pound of powder. I also cast some bullets and gave them to him.

(3) Illustrated London News (15th April, 1848)

Cuffay spoke in strong language against the dispersal of the meeting and contended that it would be time enough to evince their fear of the military when they met them face to face! He believed the whole Convention were a set of cowardly humbugs, and he would have nothing more to do with them. He then left the van, and got among the crowd, where he said that O'Connor must have known all this before, and that he ought to have informed them of it, so that they might have conveyed the petition at once to the House of Commons without crossing the bridges. They had been completely caught in a trap.

(4) William Cuffay, statement in court after being found guilty of conspiracy.

The present Government is now supported by a regular organized system of espionage which is a disgrace to this great and boasted free country. The locality to which I belong never approved of any violence of this sort and never sent any delegates to any such meetings, and that you will find proved in the trials of my fellow prisoners who have not yet been tried. They sent no delegates, and consequently there were no luminaries nor firebrands sent to Orange Street from that locality. That is another reason why I should not be sentenced; that will be hereafter proved. Then I have to complain of the Whig manoeuvres of keeping the spy Davis back to the last moment after he had had an opportunity of reading the evidence in the newspaper and seeing what was deposed to, and then coming here with a statement written out by the inspectors of police against me and filling up all the discrepancies in the evidence of the principal spy, that miscreant with so many aliases, Powell being his proper name, it seems.

I say you have no right to sentence me. Although the trial has lasted a long time, it has not been a fair trial, and my request to have a fair trial - to be tried by my equals - has not been complied with. Everything has been done to raise a prejudice against me, and the press of this country - and I believe of other countries too - has done all in its power to smother me with ridicule. I ask no pity. I ask no mercy. I expected to be convicted, and I did not think anything else. No, I pity the Government, and I pity the Attorney General for convicting me by means of such base characters. The Attorney General ought to be called the Spy General. I am not anxious for martyrdom, but after what I have endured this week, I feel that I could bear any punishment proudly, even to the scaffold.

(5) The Northern Star (7th October, 1848)

The conduct of Cuffay throughout his trial was that of a man. A somewhat singular appearance, certain eccentricities of manner, and a habit of unregulated speech, afforded an opportunity to the 'suckmug' reporters, unprincipled editors, and buffoons of the press to make him the subject of their ridicule. The 'fast men' of the press ... did their best to smother their victim beneath the weight of their heavy wit. In a great measure, Cuffay owes his destruction to the Press gang. But his manly and admirable conduct on his trial affords his enemies no opportunity either to sneer at or abuse him. His protest from first to last against the mockery of being tried a by a jury animated by class-resentments and party-hatred showed him to be a much better respecter of' the constitution than either the Attorney General or the Judges on the bench. Cuffay's last words should be treasured up by the people.

(6) The Reasoner (1849)

When hundreds of working men elected this man to audit the accounts of their benefit society, they did so in the full belief of his trustworthiness, and he never gave them reason to repent of their choice.

Cuffey's sobriety and ever active spirit marked him for a very useful man; he cheerfully fulfilled the arduous duties which devolved upon him.