Kennington Common Mass Meeting

In the spring of 1848, Feargus O'Connor decided on a new strategy that would combine several different tactics: a large public meeting, a procession and the presentation of a petition to the House of Commons. O'Connor organised the meeting to take place at Kennington Common on Monday, 10th April, 1848.

Feargus O'Connor warned the prime minister, Lord John Russell, that after the speeches he intended to lead the large crowd to Parliament where he would present a petition to the government. Russell was in a awkward position because all his political life he had campaigned for freedom of speech and universal suffrage. However, since he became prime minister in 1846, he had been unable to persuade the majority of MPs in the House of Commons to agree to parliamentary reform. Afraid that the meeting would result in a riot, Russell decided to make sure that there would be 8,000 soldiers and 150,000 special constables on duty in London that day. In return for allowing the meeting to take place, Russell asked Feargus O'Connor not to take the crowd and the petition to Parliament.

The meeting took place without violence. Feargus O'Connor claimed that over 300,000 assembled at Kennington Common, but others argued that this figure was a vast exaggeration. The government said it was only 15,000 and The Times reporter estimated that it was probably about 20,000. The Sunday Observer, a newspaper fairly sympathetic to parliamentary reform, suggested that the true figure was around 50,000.

Feargus O'Connor also told the crowd that the petition contained 5,706,000 signatures. However, when examined by MPs it was only 1,975,496, and many of these were clear forgeries. O'Connor's many enemies in the parliamentary reform movement accused him of destroying the credibility of Chartism. His behaviour at Kennington Common did not help the reform movement and Chartism went into rapid decline after April 1848.

Primary Sources

(1) The Sunday Observer (16th April, 1848)

The metropolis presented on Monday a scene of unusual excitement and alarm. The determination announced by the members of the Chartist National Convention to hold their meeting and procession in defiance of the law and the constituted authorities - the military preparations, almost unparalleled for extent and completeness to put down any insurrectionary attempts.

The weather was exceedingly favourable for the demonstration; no obstruction was offered by the police to the processions which left the Middlesex side of London for Kennington Common; a free thoroughfare was permitted to all who wished to take part in the public meeting; and yet, instead of the 300,000 persons who, we were told would assemble on Kennington Common does not reach 50,000

(2) The Illustrated London News (14th April, 1848)

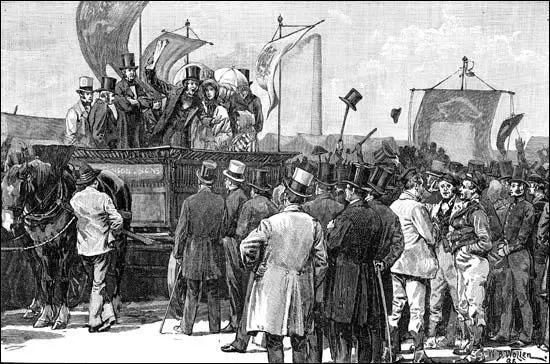

The van (a horse-drawn cart) waiting for the delegates was inscribed on the right side with the motto, 'The Charter. No surrender. Liberty is worth living for and worth dying for'; on the left, "The voice of the people is the voice of God'; while on the back of the car was inscribed, 'Who would be a slave that could be free? Onward, we conquer; backward we fall.'

(3) Feargus O'Connor, speech at Kennington Common (10th April, 1848)

My children, have now for a quarter of a century been mixed up with the democratic movement - in Ireland since 1822, and in England from the year 1833. I have always, in and out of Parliament, contended for your rights, and I have received more than 100 letters, telling me not to come here today, or my life would be sacrificed. My answer was, that I would rather be stabbed in the heart than abstain from being in my place. And my children, for you are my children, and I am only your father and bailiff; but I am your fond father and your unpaid bailiff.

My breath is nearly gone, and I will only say, when I desert you may desert me. You have by your conduct today more than repaid me for all I have done for you, and I will go on conquering until you have the land and the People's Charter becomes the law of the land.

(4) Lord John Russell, letter to Queen Victoria (11th April, 1848)

The Kennington Common Meeting has proved a complete failure. About 12,000 or 15,000 persons met in good order. Feargus O'Connor was told that the meeting would not be prevented, but that no procession would be allowed to pass the bridges. He then addressed the crowd, advising them to disperse, and went off in a cab to the Home Office (where he handed over the petition).

(5) Charles Greville, government official working in London, diary entry (13th April, 1848)

Monday passed off with surprising quiet. Enormous preparations were made, and a host of military, police, and special constables were ready if wanted. The Chartist movement was contemptible. Everybody was on the alert. Our office was fortified and all our guns were taken down to be used in defence of the building.

(6) George Sims, My Life (1917)

My grandfather, John Dinmore Stevenson, was one of the leaders of the Chartist movement. In 1848 the Chartists made the strategic mistake of threatening to use force in order to obtain their demands. My grandfather went off to join the Chartists in the great demonstration on Kennington Common, and to act as one of the leaders in the threatened advance upon Westminster, and my father was at the same time sworn in as a special constable, and armed with his staff of office went forth to protect London from my grandfather.

The Kennington Common affair was a terrible fiasco. The heavens, I believe, wept over it so profusely that the ardour of the rebels was damped in the deluge. My grandfather came back to our house soaked to the skin, changed his clothes, and sat down to tea with the special constable. And there was peace between them.

Student Activities

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

The Chartists (Answer Commentary)

Women and the Chartist Movement (Answer Commentary)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)