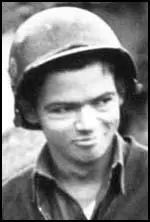

Bill Mauldin

Bill Mauldin was born in Mountain Park, New Mexico on 29th October, 1921. While in his early teens Mauldin decided he wanted to become a professional cartoonist and after school attended the Academy of Fine Art in Chicago.

He joined the United States Army in 1940 and began producing cartoons for the 45th Division News. In 1943 he took part in the invasions of Sicily and Italy. The following year he became a full-time cartoonist for the Stars and Stripes. His cartoons often featured two infantrymen called Willie and Joe.

After Ernie Pyle, America's most popular journalist in the Second World War, wrote an article about the work of Mauldin, he was picked up by United Feature Syndicate in 1944 and his cartoons began appearing in newspapers all over the United States. He later recalled that: "I drew pictures for and about the soldiers because I knew what their life was like and understood their gripes. I wanted to make something out of the humorous situations which come up even when you don't think life could be any more miserable."

In his autobiography, Up Front (1945) Mauldin argued: "The surest way to become a pacifist is to join the infantry. I don't make the infantryman look noble, because he couldn't look noble even if he tried. Still there is a certain nobility and dignity in combat soldiers and medical aid men with dirt in their ears. They are rough and their language gets coarse because they live a life stripped of convention and niceties. Their nobility and dignity come from the way they live unselfishly and risk their lives to help each other. They are normal people who have been put where they are, and whose actions and feelings have been molded by their circumstances. There are gentlemen and boors; intelligent ones and stupid ones; talented ones and inefficient ones."

Bill Mauldin, Stars and Stripes (1944)

During the war Mauldin developed the characters, Willie and Joe. He later told Studs Terkel: "Willie and Joe were really drawn on guys I knew in this infantry company. It was a rifle company from McAlester, Oklahoma. There were Indians in it and a lot of laconic good ol' boys. These two guys were based on these Oklahomans I knew. People like that really make ideal infantry soldiers. Laconic, they don't take anything too seriously. They're not happy doing what they're doing, but they're not totally fish out of water, either. They know how to walk in the mud and how to shoot. It's a southwestern sort of trait, really. Don't take any crap off anybody."

Mike Anton has argued: "His darkly funny and irreverent cartoons captured the mood of a changing military made up of citizen soldiers who questioned the leadership skills of their officers even as they battled the enemy. Mauldin went on to become one of the best-known and best-loved newspaper cartoonists in America. Mauldin's Willie and Joe were dirty and unshaven, slogging through mud and snow and sleeping in foxholes filled with water. They dodged the enemy's bullets as well as the poor morale brought on by incompetent officers."

Mauldin's cartoons often reflected his anti-authoritarian views and this got him in trouble with some of the senior officers. In 1945 General George Patton wrote a letter to the Stars and Stripes and threatened to ban the newspaper from his Third Army if it did not stop carrying "Mauldin's scurrilous attempts to undermine military discipline." General Dwight D. Eisenhower did not agree and feared that any attempt at censorship would undermine army morale. He therefore arranged a meeting between Mauldin and Patton. Mauldin went to see Patton in March 1945 where he had to endure a long lecture on the dangers of producing "anti-officer cartoons". Mauldin responded by arguing that the soldiers had legitimate grievances that needed to be addressed.

Will Lang, a reporter with Time, heard about the meeting and questioned Mauldin about what happened. Mauldin replied, "I came out with my hide on. We parted friends, but I don't think we changed each other's mind." When the comment appeared in the magazine George Patton was furious and commented that if he came to see him again he would throw him in jail. Mauldin later recalled: "I always admired Patton. Oh, sure, the stupid bastard was crazy. He was insane. He thought he was living in the Dark Ages. Soldiers were peasants to him. I didn't like that attitude, but I certainly respected his theories and the techniques he used to get his men out of their foxholes."

In 1945, Mauldin's cartoons on the Second World War won the Pulitzer Prize. The citation read: "for distinguished service as a cartoonist, as exemplified by the series entitled "Up Front With Mauldin". Mauldin, the youngest person to be awarded the prize, was now one of the best-known cartoonists in the United States.

Bill Mauldin took advantage of his popularity by publishing a series of books including Up Front (1945), Willie & Joe: Stars and Stripes (1945), Willie and Joe: Back Home (1947), A Sort of a Saga (1949), Bill Mauldin's Army (1951), Bill Mauldin in Korea (1952) and Up High (1956).

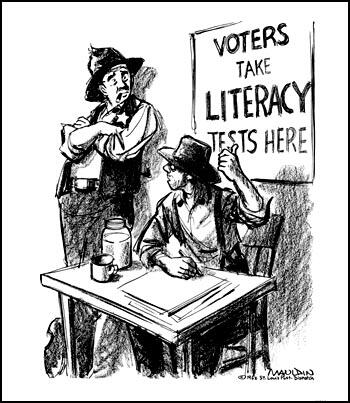

As a member of the United Feature Syndicate Bill Mauldin's cartoons attacking racism, the Ku Klux Klan and McCarthyism appeared in newspapers all over the United States. Mauldin's cartoons were unpopular with the newspapers in small towns and he had difficulty getting them published. Disillusioned, Mauldin gave up cartooning for a period.

Mauldin, a member of the Democratic Party ran unsuccessfully for the United States Congress in New York's 28th Congressional District. He later recalled: "I jumped in with both feet and campaigned for seven or eight months.... I was a very sincere candidate, but when they would ask me questions that had to do with foreign policy or national policy, obviously I was pretty far to the left of the mainstream up there. Again, I'm an old Truman Democrat, I'm not that far left, but by their lives I was pretty far left."

In 1958 Mauldin replaced the retiring Daniel Fitzpatrick at the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. This newspaper was willing to publish his strong political views. In 1959 he won another Pulitzer Prize for his cartoon, I won the Nobel Prize for Literature. What was your crime?

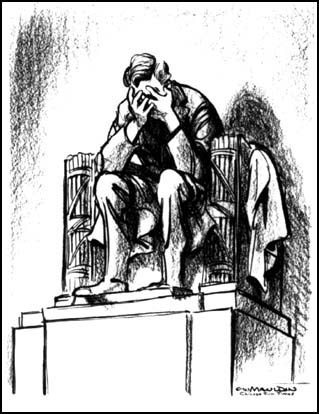

In 1962 Mauldin moved to the Chicago Sun-Times where he worked with another radical cartoonist, Jacob Burck. His drawing of a crying Abraham Lincoln on the death of John F. Kennedy, became one of the most famous cartoons in American history.

Bill Mauldin, St. Louis Post-Dispatch (15th May 1962)

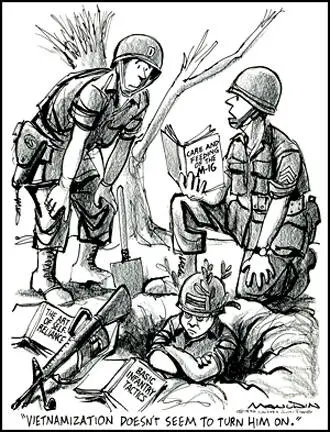

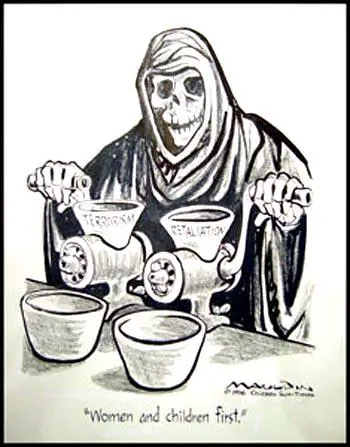

Bill Mauldin, Women and Children First (c. 1980)

Other books by Mauldin included What's Got Your Back Up? (1961), I've Decided I Want My Seat Back (1965), The Brass Ring (1971), Mud and Guts (1978), Hurray for B.C. (1979) and Let's Declare Ourselves Winners and Get the Hell Out (1985).

Bill Maudlin died of respiratory failure at a nursing home in Newport Beach, California, on 22nd January, 2003.

Primary Sources

(1) Bill Maudlin, Up Front (1945)

The surest way to become a pacifist is to join the infantry. I don't make the infantryman look noble, because he couldn't look noble even if he tried. Still there is a certain nobility and dignity in combat soldiers and medical aid men with dirt in their ears. They are rough and their language gets coarse because they live a life stripped of convention and niceties.

Their nobility and dignity come from the way they live unselfishly and risk their lives to help each other. They are normal people who have been put where they are, and whose actions and feelings have been molded by their circumstances. There are gentlemen and boors; intelligent ones and stupid ones; talented ones and inefficient ones.

But when they are all together and they are fighting, despite their bitching and griping and goldbricking and mortal fear, they are facing cold steel and screaming lead and hard enemies, and they are advancing and beating the hell out of the opposition.

They wish to hell they were someplace else, and they wish to hell they would get relief. They wish to hell the mud was dry and they wish to hell their coffee was hot. They want to go home. But they stay in their wet holes and fight, and then they climb out and crawl through minefields and fight some more.

(2) Bill Maudlin wrote about his meeting with General George Patton in his book, The Brass Ring (1971)

There he sat, big as life even at that distance. His hair was silver, his face was pink, his collar and shoulders glittered with more stars than I could count, his fingers sparkled with rings, and an incredible mass of ribbons started around desktop level and spread upward in a flood over his chest to the very top of his shoulder, as if preparing to march down his back too. His face was rugged, with an odd, strangely shapeless outline; his eyes were pale, almost colorless, with a choleric bulge. His small, compressed mouth was sharply downturned at the comers, with a lower lip which suggested a pouting child as much as a no-nonsense martinet. It was a welcome, rather human touch. Beside him, lying in a big chair, was Willie, the bull terrier. If ever dog was suited to master this one was. Willie had his beloved boss's expression and lacked only the ribbons and stars. I stood in that door staring into the four meanest eyes I'd ever seen.

Patton demanded: "What are you trying to do, incite a goddamn mutiny?" Patton then launched into a lengthy dissertation about armies and leaders of the past, of rank and its importance. Patton was a master of his subject felt truly privileged, as if I were hearing Michelangelo on painting. I had been too long enchanted by the army myself to be anything but impressed by this magnificent old performer's monologue. Just as when I had first saluted him, I felt whatever martial spirit was left in me being lifted out and fanned into flame.

If you're a leader, you don't push wet spaghetti, you pull it. The U.S. Army still has to learn that. The British understand it. Patton understood it. I always admired Patton. Oh, sure, the stupid bastard was crazy. He was insane. He thought he was living in the Dark Ages. Soldiers were peasants to him. I didn't like that attitude, but I certainly respected his theories and the techniques he used to get his men out of their foxholes.

(3) Frederick S. Voss wrote about the meeting between Bill Maudlin and George Patton in his book, Reporting the War (1994)

Pulling from a drawer some clipped samples of Mauldin's work, he asked their creator to justify their anti-officer tone. In doing so, Mauldin thought he acquitted himself fairly well. By making soldiers laugh at their grievances and letting them know that someone else understood them, he said in effect, he was helping them to let off steam in a relatively harmless way and thereby preventing the mutiny that Patton was so sure he was causing. Patton was clearly unconvinced. "You can't run an army like a mob," he declared when Mauldin was done, and after a handshake and a smart parting salute from Mauldin, the interview was over.

(4) Studs Terkel interviewed Bill Mauldin about his experiences during the Second World War for his book, The Good War (1985)

Willie and Joe were really drawn on guys I knew in this infantry company. It was a rifle company from McAlester, Oklahoma. There were Indians in it and a lot of laconic good ol' boys. These two guys were based on these Oklahomans I knew. People like that really make ideal infantry soldiers. Laconic, they don't take anything too seriously. They're not happy doing what they're doing, but they're not totally fish out of water, either. They know how to walk in the mud and how to shoot. It's a southwestern sort of trait, really. Don't take any crap off anybody.

I think Willie and Joe would have voted for Roosevelt cynically, sardonically, with a lot of reservations. He really wasn't their cup of tea. They would have considered Roosevelt too much of a bleeding heart. They couldn't bring themselves to be Republicans. Someone like Harry Truman would be more their cup of tea. I'm really expressing my own feelings. I dug Truman. I still do. It really shows you what my limitations are.

Willie and Joe are my creatures. Or am I their creature? They are not social reformers. They're much more reactive. They're not social scientists and I'm not a social scientist. We're moral people who do not belong to the moral majority. One of my principles is, Thou shall not bully. The only answer is to muscle the bully. I'm very combative that way.

I was twenty-two when I got home to two hundred papers printing my stuff. The Stars & Stripes released my stuff for syndication. I'd done a book during the last year of the war and the Book-of-the-Month Club picked it up. Up Front was number one on the bestseller list for about eighteen months. I came home, and here all my friends were on 52-20. My book sold something like three million in hardcover. Elsenhower and I made the same amount of money on our books. Congress rammed through a special law letting him claim capital gains on it. He kept what I paid, I paid what he kept. He paid capital gains, I paid through the nose. My income tax was in the hundreds of thousands. I remember signing one check for $600,000. Here I was twenty-three, twenty-four years old, fresh out of the war. I felt like a war profiteer, and here were all my friends on 52-20. I might have gone in as an average citizen but I came out as something else.

(5) Mike Anton, Los Angeles Times (23rd January, 2003)

Bill Mauldin, the Pulitzer Prize-winning cartoonist whose characters, the downtrodden GIs Willie and Joe, spoke to a generation of soldiers who fought in World War II, died early yesterday. He was 81.

Mauldin died at a nursing home in Newport Beach, Calif., where he had lived since mid-2001 while battling Alzheimer's disease. More recently, he had contracted pneumonia. The cause of death was respiratory failure.

A self-described "hillbilly from New Mexico," Mauldin rose from small-town obscurity to cult hero as a baby-faced Army sergeant working in Europe for the armed forces newspaper Stars & Stripes.

His darkly funny and irreverent cartoons captured the mood of a changing military made up of citizen soldiers who questioned the leadership skills of their officers even as they battled the enemy. Mauldin went on to become one of the best-known and best-loved newspaper cartoonists in America.

Mauldin's Willie and Joe were dirty and unshaven, slogging through mud and snow and sleeping in foxholes filled with water. They dodged the enemy's bullets as well as the poor morale brought on by incompetent officers.

Student Activities

Economic Prosperity in the United States: 1919-1929 (Answer Commentary)

Women in the United States in the 1920s (Answer Commentary)

Volstead Act and Prohibition (Answer Commentary)

The Ku Klux Klan (Answer Commentary)

Classroom Activities by Subject