Otto Dix

Otto Dix, the eldest son of Franz Dix (1862-1942), an iron foundry worker, and Louise Amann (1864-1953), a seamstress, was born in Unternhaus, Germany, on 2nd December, 1891. He spent a lot of time with his cousin, Fritz Amann, who was attempting to make a living as an artist. (1)

After attending elementary school he worked locally. In 1906 he started an apprenticeship with painter Carl Senff, and began painting his first landscapes. In 1910 he became a student at the Dresden School of Arts and Crafts. To help fund his education, he accepted commissions and painted portraits of local people. (2)

On the outbreak of the First World War in 1914 Dix volunteered for the German Army and was assigned to a field artillery regiment in Dresden. He later recalled why he joined the army: "I had to experience how someone beside me suddenly falls over and is dead and the bullet has hit him squarely. I had to experience that quite directly. I wanted it. I'm therefore not a pacifist at all - or am I? - perhaps I was an inquisitive person. I had to see all that for myself. I'm such a realist, you know, that I have to see everything with my own eyes in order to confirm that it's like that. I have to experience all the ghastly, bottomless depths for life for myself; it's for that reason that I went to war, and for that reason I volunteered." (3)

In the autumn of 1915 Dix was sent to the Western Front where he served as a non-commissioned officer with a machine-gun unit. He was at the Somme during the major allied offensive during the summer of 1916. Dix was wounded several times during the war. On one occasion he nearly died when a shrapnel splinter hit him in the neck. His experiences on the front line had a dramatic impact on his art: "War is so bestial: hunger, lice, mud, those insane noises... I had the feeling, on looking at the pictures from my early years, that I had completely missed one side of reality so far, namely the ugly aspect." (4)

In November 1917 his unit was transferred to the Eastern Front and after Russia negotiated a peace with Germany, Dix returned to France where he took part in the German Spring Offensive. In August of that year he was wounded in the neck. By the end of the war in 1918, Dix had won the Iron Cross (second class) and reached the rank of vice-sergeant-major. He was discharged from service on 22nd December 1918. (5)

Otto Dix and the First World War

After the war Dix developed left-wing views and his paintings and drawings became increasingly political. Like other German artists such as John Heartfield and George Grosz, Dix became what they called "revolutionary pacifists". As Jonathan Jones has pointed out: "It was not at all obvious that a man such as Dix would create some of the defining pacifist images of the 20th century. In 1914 he was a fierce German patriot who joined up enthusiastically. He became a machine gunner and fought at the Battle of the Somme, efficiently mowing down British troops. He won the Iron Cross (second class) and began training to be a pilot. How did this courageous soldier turn into an anti-war artist? To understand that, we need to comprehend that, during the first world war, a radical minority of Germans turned to artistic and political revolution, rather than nationalism. Like the British war poets, Germany's young artists came to hate the war, but unlike the poets, they organised to resist it." (6)

Otto Dix told Maria Wetzel: "As a young man you don't notice at all that you were, after all, badly affected. For years afterwards, at least ten years, I kept getting these dreams, in which I had to crawl through ruined houses, along passages I could hardly get through. Not that painting would have been a release. The reason for doing it is the desire to create. I've got to do it! I've seen that, I can still remember it, I've got to paint it." (7)

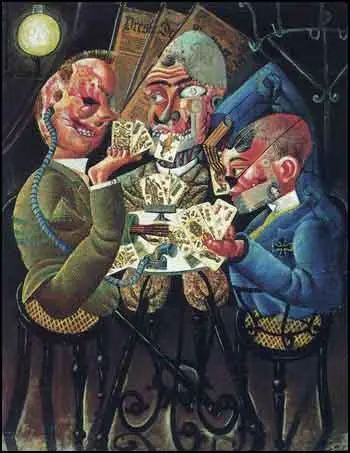

It has been argued by Uwe M. Schneede that Otto Dix was one of the founders of modern Verism (the artistic preference of contemporary everyday subject matter instead of the heroic or legendary in art): "From the garish over-emphasised effects of his Dadaist beginnings he came via the study of the art of previous centuries - especially of old German masters and their technique - to his ponderously constructed pictures, precise in every detail, in which the object is kept balanced between an almost aggressive here-and-now and a removal from reality." (8)

One of his most powerful paintings was The Skat Players (1920). Influenced by the work of John Heartfield, it shows "card-playing cripples... a nightmarish vision of people so mutilated that the scarred remains are scarcely human. Arms, legs, jaws, ears and noses shot away, these men function only as a series of spare parts cobbled together, and their construction is paralleled in the way the picture has been made: it is an elaborate collage, the painted parts combined with glued-on playing-cards, newspapers and bits of wood." (9)

In 1920 George Grosz, John Heartfield and Raoul Hausmann organised the Erste Internationale Dada-Messe in the Berlin gallery owned by Otto Burchard. It was a comprehensive manifestation of Dada (a movement consisted of artists who rejected the logic, reason, and aestheticism of modern capitalist society, instead expressing nonsense, irrationality, and anti-bourgeois protest in their works). Among the 174 works in the exhibition were pictures by Dix, Grosz, Heartfield, Hausmann, Max Ernst, Hannah Höch and Rudolf Schlichter. "The text on the panels accompanying each exhibit was partly Dadaist-polemical, partly political." (10)

Dix was angry about the way that the wounded and crippled ex-soldiers were treated in Germany. This was reflected in paintings such as War Cripples (1920), Butcher's Shop (1920) and War Wounded (1922). In October, 1923 Dix's large painting, The Trench, was purchased by the Wallraf-Richartz Museum. The museum's director, Hans F. Secker, assured him that it had been acquired "not without blood and sweat". He added that when the new collection was to be opened to the public in December "your painting will most likely be the greatest sensation." (11)

Walter Schmits, writing in The Kölnische Zeitung, commented: "In the cold, sallow, ghostly light of dawn…a trench appears into which a devastating bombardment has just descended. A poisonous sulphur yellow pool glistens in the depths like a smirk from hell. Otherwise the trench is filled up with hideously mutilated bodies and human fragments. From open skulls brains gush like thick red groats; torn-up limbs, intestines, shreds of uniforms, artillery shells form a vile heap... Half-decayed remains of the fallen, which were probably buried in the walls of the trench out of necessity and were exposed by the exploding shells, mix with the fresh, blood covered corpses. One soldier has been hurled out of the trench and lies above it, impaled on stakes." (12)

When the painting was exhibited in 1924 its depiction of decomposed corpses in a German trench created such a public outcry that the museum's director hid the painting behind a curtain. The local newspaper demanded that the painting should be returned to the artist. Whereas a journalist claimed that the painting had received so much publicity that it had increased the number of people who had seen it. Another critic described it as "perhaps the most powerful as well as well as the most anti-war statements in modern art". In 1925 the then-mayor of Cologne, Konrad Adenauer, cancelled the purchase of the painting and forced Secker to resign. (13)

During the First World War, Dix had limited opportunities to paint pictures. However, he did make a large number of sketches. In 1924 Dix joined with other artists who had fought in the First World War to put on a travelling exhibition of paintings called No More War! Dix also produced a book of etchings, The War (1924). Tom Lubbock described the book as "a series of astonished snapshots, each of which might have the motto: I can't believe that I saw this, but I did." (14)

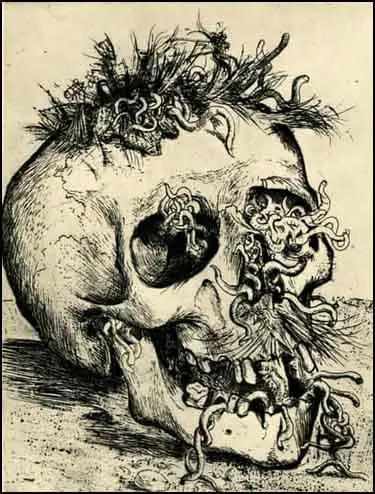

Hilton Kramer, argued that the people who visited the exhibition would have found it a difficult experience: "The total effect of these images of violence, suffering and death is so grim and so powerful that it’s likely to leave more tender-hearted visitors to the exhibition reeling from the experience. Even though we read about similar horrors in the newspapers every day... such graphic depictions of violent death remain far more disturbing than the printed word." (15)

Another critic commented: "A German soldier sits in a trench, resting against its muddy wall. He is smiling, but the grin is empty and hollow-eyed – for his face is a bare skull. He has been dead a while. No one bothered to bury him. His helmet is still on his skull, and his boots reveal a rotting ankle. In another print, a severed skull lies on the earth. Grass has grown on its crown. More grass resembles a moustache under its nose. Out of the eyes, vegetation bursts. Worms crawl sickeningly out of a gaping mouth." (16)

The New Realism

Frank Whitford has argued that the work of artists such as Otto Dix, developed what became known as the New Realism. "They had grown weary of the years of hectic experimentation that had preceded the war and that they were tired of all kinds of art that were highly subjective, metaphysical, esoteric and accessible only to an elite. They wanted to return to subjects that were familiar to everyone, painted in a way which everyone could understand. Some of them were content simply to mirror common experience of mundane things. Others, more politically inspired, preferred to angle the mirror so that the dark side of society was revealed. All of these artists cultivated a painstakingly realistic style which emulated the smooth, anonymous surface of the photograph." (17)

Dix's artist friends such as George Grosz and John Heartfield joined with Paul Levi, Willie Munzenberg, Clara Zetkin, Ernst Toller, Walther Ulbricht, Heinrich Blücher, Julian Marchlewski, Ernst Thälmann, Hermann Duncker, Hugo Eberlein, Paul Frölich, Wilhelm Pieck, Franz Mehring, and Ernest Meyer. to form the German Communist Party (KPD). Over the next few years Grosz and Heartfield produced designs and posters for the organization. (18) Dix had original agreed with them about politics but refused to join the KPD. When a friend asked him to join he replied: "I don't want to hear about your stupid politics - I'd rather spend the 5 marks' membership fee on a whore." (19)

Metropolis (1928)

Dix worked for six years on what is considered to be one of his two great masterpieces, Metropolis (1928). It is a triptych (a painting on three panels side by side). With "dazzling colour and great richness of invention, he embodied his vision of Berlin at the height of its frenzied decadence of the 1920s." In the left-hand panel, Dix shows himself as a war cripple entering Berlin and being greeted by a row of beckoning prostitutes. "Bleating saxophones coax customers on to the dance floor. The whores outside tell beggars to get lost and a man with a prosthetic jaw, give a mock salute top passing transvestites." (20)

Dix's experiences in the First World War served to make him particularly sensitive to the hypocrisy of post-war bourgeois society, a hypocrisy which he recognized as the product of mental suppression. "People did not want to see the innumerable war cripples lining the streets, not wishing to be reminded of the disastrous years. People dressed up, donned masks, did anything to avoid being themselves, and lost themselves in the temples of pleasure. Dix created a monument to this society in his Metropolis Triptych, one pushed to extremes through its employment of the sacred form of the triptych." (21)

Otto Dix became preoccupied with the violent excesses of city life in the Weimar Republic. "He came to believe that everyday crime was the reflex to and continuation of the lunacy of war: The catastrophe had began. I drew drunks, people throwing up, men shaking their fists at the moon as they cursed it, the murderers of women, playing at cards while sitting on a create in which the murder victims could be seen... I drew a man looking around him fearfully, washing his hands, which had blood on them." (22)

In 1927 Otto Dix was given a professorship at the Dresden School of Arts and Crafts. His interest during this period was focused solely upon people. Only in extremely rare instances were his portraits commissioned works. Instead he embarked on a constant search for personalities who could provide information about their time. He sought models in cafe, in the street, and within his circle of friends who would reflect the changes taking place in society. (23)

Sylvia von Harden, the journalist, recalls how Dix met her in the street: "I must paint you! I simply must! You are representative of an entire epoch! So, you want to paint my lack-luster eyes, my ornate ears, my long nose, my thin lips; you want to paint my long hands, my short legs, my big feet - things which can only scare people off and delight no-one? You have brilliantly characterized yourself, and all that will lead to a portrait representative of an epoch concerned not with the outward beauty of a woman but rather with her psychological condition." (24) The portrait shows von Harden with bobbed hair and monocle, seated at a cafe table with a cigarette in her hand and a cocktail in front of her. (25)

Trench Warfare (1932)

Ernst Friedrich, published his book of photographs of German soldiers who had been badly disfigured by warfare. Dix made extensive use of these photographs when he returned to the subject of war. In 1928 he said: "People were already beginning to forget what horrible suffering the war had brought them." He completed the second of his masterpieces, Trench Warfare in 1932. It was a painting that attempted to drain war of any heroism or nobility. (26)

Trench Warfare, like his other masterpiece, Metropolis (1928) is a triptych. Very popular in medieval times, this form was usually used to make altar-pieces. It has three main panels, with a fourth as a supporting panel or predella below the main central panel. This panel is based on The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb by Hans Holbein.The large central panel is a 204 cm (80 in) square; the flanking panels to either side the same height but half the width, 102 cm (40 in) each; and the predella below the central panel has the same width but is only 60 cm (24 in) high. The left-handed panel shows German soldiers marching off to war, the central panel is a scene of destroyed houses and mangled bodies, and the right-hand panel side panel shows soldiers struggling home from the war. (27)

Nazi Germany

On 4th January, 1933, Adolf Hitler had a meeting with Franz von Papen and decided to work together for a government. It was decided that Hitler would be Chancellor and Von Papen's associates would hold important ministries. "They also agreed to eliminate Social Democrats, Communists, and Jews from political life. Hitler promised to renounce the socialist part of the program, while Von Papen pledged that he would obtain further subsidies from the industrialists for Hitler's use... On 30th January, 1933, with great reluctance, Von Hindenburg named Hitler as Chancellor." (28)

Most of his artistic friends, including George Grosz and John Heartfield, fled Nazi Germany. As Dix had not been critical of Hitler he thought he would be safe. He justified his non-political stance by the words: "Artists shouldn't try to improve and convert they're far too insignificant for that. They must only bear witness." However, Hitler hated Dix's anti-war paintings and he was sacked as professor at the Dresden School of Arts and Crafts. Dix's dismissal letter said that his work "threatened to sap the will of the German people to defend themselves." (29)

Otto Dix continued to paint pictures about the First World War. An example of this was Flanders (1934), a painting that shows a scene from the Western Front. Dix later claimed was Inspired by a passage from Under Fire, a novel written by the French soldier, Henri Barbusse. In the picture dead bodies float in water-filled shell-holes while those soldiers still alive resemble rotting tree stumps. "The central figure, a soldier, shelters behind a tree stump, trying to snatch some sleep before once more going into battle. The landscape is completely obliterated, leaving only destroyed buildings and trees, and water-filled shell craters. All around are dead, wounded or exhausted men, who lie or sit in a morass of mud while the sky appears to bear down on them, dark but for the restricted orange glow of the sun." (30)

On 27th November, 1936, Joseph Goebbels issued the following decree: "On the express authority of the Führer, I hereby empower the President of the Reich Chamber of Visual Arts, Professor Ziegler of Munich, to select and secure for an exhibition works of German degenerate art since 1910, both painting and sculpture, which are now in collections owned by the German Reich, by provinces, and by municipalities. You are requested to give Professor Ziegler your full support during his examination and selection of these works." (31)

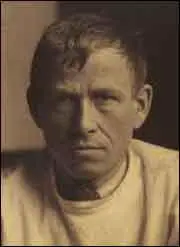

It is estimated that 260 of Otto Dix's works were confiscated. "He was despised by Hitler not just because he drew and painted in a spiky, gnarled, ghoulish way that decried the ravages of World War I and spoke to Weimar anxiety, but because his art mocked the German idea of heroism. The Munich self-portrait conveys a pride that seems ready to vanquish an enemy that had not quite appeared on the scene when Dix painted the work in 1919 but that both he and his art would outlast." (32)

Other artists who suffered included Emil Nolde (1,052), Erich Heckel (729), Karl Schmidt-Rottluff (688), Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (639), Max Beckmann (509), Christian Rohlfs (418), Oskar Kokoschka (417), Lyonel Feininger (378), Ernst Barlach (381), Otto Müller (357), Karl Hofer (313), Max Pechstein (326), Lovis Corinth (295), George Grosz (285), Franz Marc (130), Paul Klee (102), Paula Modersohn-Becker (70) and Kathe Kollwitz (31). The campaign against "degenerate art" took in work by 1,400 artists in all. (33)

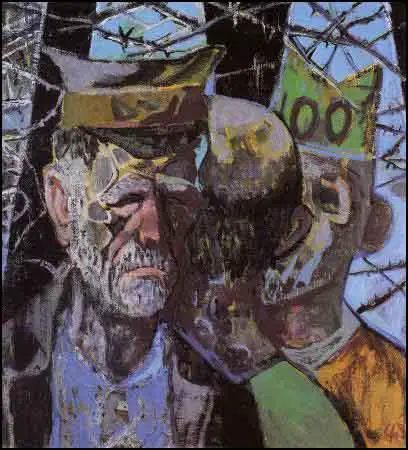

The Exhibition of Degenerate Art opened in Munich on 19th July, 1937. It included 650 works of art confiscated from 32 German museums. The exhibition travelled to twelve other cities from 1937 to 1941. In all, the show drew more than 3 million visitors. The exhibition sought to demonstrate the “degeneration” of artworks by placing them alongside drawings done by the mentally retarded and photographs of the physically handicapped. Dix's work was placed in a section that were considered to be "art as a tool of Marxist propaganda against military service". It was claimed that in these works "German soldiers were depicted as idiots, sexual degenerates and drunks." (34)

Dix, like all other artists, was forced to join the Nazi government's Reich Chamber of Fine Arts (Reichskammer der bildenden Kuenste), a subdivision of Goebbels' Cultural Ministry (Reichskulturkammer). Membership was mandatory for all artists in the Reich. Otto Dix had to promise to paint only inoffensive landscapes or portraits. According to one of his biographers, Otto Conzelmann, Dix still painted an occasional allegorical painting that criticized Nazi ideals. (35)

Second World War

In 1939 Dix was arrested and charged with involvement in a plot on Hitler's life that had taken place in Munich. . However, he was eventually released and the charges were dropped. In the Second World War Dix was conscripted into the Volkssturm (German Home Guard). In 1945 Dix was forced to join the German Army and at the end of the war was captured by the French Army and was put into a prisoner-of-war camp. (36)

Released in February 1946, Dix returned to Dresden, a city that had been virtually destroyed by heavy bombing. Most of Dix's post-war paintings were religious allegories. However, paintings such as Job (1946), Masks in Ruins (1946) and Ecce Homo II (1948) dealt with the suffering caused by the Second World War. He also painted the anguished Self Portrait as Prisoner of War (1947) in which the barbed wire evokes the crown of thorns of the Crucifixion. (37)

Otto Dix died on 25th July, 1969.

Primary Sources

(1) In 1963 Otto Dix explained why he had joined the German Army on the outbreak of the First World War in 1914.

I had to experience how someone beside me suddenly falls over and is dead and the bullet has hit him squarely. I had to experience that quite directly. I wanted it. I'm therefore not a pacifist at all - or am I? - perhaps I was an inquisitive person. I had to see all that for myself. I'm such a realist, you know, that I have to see everything with my own eyes in order to confirm that it's like that. I have to experience all the ghastly, bottomless depths for life for myself; it's for that reason that I went to war, and for that reason I volunteered.

(2) Otto Dix, interviewed by Maria Wetzel (1963)

As a young man you don't notice at all that you were, after all, badly affected. For years afterwards, at least ten years, I kept getting these dreams, in which I had to crawl through ruined houses, along passages I could hardly get through.

Not that painting would have been a release. The reason for doing it is the desire to create. I've got to do it! I've seen that, I can still remember it, I've got to paint it.

(3) Otto Dix, Neues Deutschland (December, 1964)

The painting (Trench Warfare) began life ten years after the First World War. During this time I had made a lot of studies, so that I could give artistic expression to my war experiences. In 1928 I felt ready to tackle the big subject. At this time there were a lot of books in the Weimar Republic once again peddling the notions of the hero and heroism, which had long been rendered absurd in the trenches of the First World War. People were already beginning to forget, what horrible suffering the war had brought them. I did not want to cause fear and panic, but to let people know how dreadful war is and so to stimulate people's powers of resistance.

(4) Julius Meier-Graefe reviewed Otto Dix's painting, The Trench, in July, 1924.

The trench is not only badly, but disgracefully painted, with a penetrating delight in detail, not I hasten to add, in sensuous detail but in matter-of-fact detail. Brains, blood and entrails can be painted in a way which make's one's mouth water. This Dix - forgive the crude expression - makes you want to throw up.

(5) Otto Dix's painting, Flanders, was inspired by a passage from Le Fe, a First World War novel written by the French soldier, Henri Barbusse.

In the same place, where we had thrown ourselves down in the night, we wait for daybreak. Half dosing, half sleeping, continually opening and closing our eyes, paralyzed, shattered and freezing, we stare in disbelief at the return of the light. Painfully and swaying like an invalid, I raise myself up and look around. The oppressive weight of my wet greatcoat pulls me down. Next to me lie three completely disfigured shapes.

(6) Hilton Kramer, The Observer (29th May, 2008)

Given the horrific history of Germany in the modern era, it was not to be expected that German art from the period would have much to do with scenarios of sweetness and light. A culture of violence and intolerance was bound to produce an art dominated by violent emotions and a sense of dislocation and loss. Exactly how individual talents respond to such extreme situations depends, however, not only on their artistic gifts but on the moral compass that each brings to such a daunting challenge.

It’s one of the many virtues of War/Hell: Master Prints by Otto Dix and Max Beckmann, the new exhibition at the Neue Galerie, that it gives us such vivid accounts of the way two tough-minded artists confronted this challenge without in any way minimizing its gravity or otherwise avoiding its tragic implications. Both artists had the misfortune of having had firsthand experience of trench warfare in the First World War - Beckmann as a medical orderly who suffered a nervous breakdown, Dix as a foot soldier in the trenches whose vision of life remained permanently defined (and permanently impaired) by his encounter with battlefield carnage.

Yet in their art, they brought very different sensibilities to the depiction of the horrors that shaped them. Otto Dix (1891-1969) was essentially a draftsman and caricaturist, even in his paintings, whereas Max Beckmann (1884-1950) was a humanist of heroic stature—an artist for whom the highest aspirations of the Old Masters continued to serve as an inspiration, even in the face of the catastrophe he felt compelled to deal with in his art.

As its title indicates, the exhibition is primarily devoted to the artists’ prints: the series of 12 large-format lithographs by Beckmann entitled Die Hölle (Hell), printed in 1919, and the portfolio of 50 prints by Otto Dix entitled Der Krieg (War), published in 1924. The total effect of these images of violence, suffering and death is so grim and so powerful that it’s likely to leave more tender-hearted visitors to the exhibition reeling from the experience. Even though we read about similar horrors in the newspapers every day, owing to the wars in Iraq and elsewhere, such graphic depictions of violent death remain far more disturbing than the printed word.

It has to be said, however, that it’s only in the high-intensity subject matter of these print portfolios that Dix and Beckmann can be thought to occupy common artistic ground. Elsewhere in their respective oeuvres, the scale and quality of their accomplishments are significantly unequal. As a painter, Max Beckmann occupies a place among the giants of 20th-century art. His series of heroic triptychs constitutes an achievement that, in my judgment, rivals even that of Picasso’s Guernica for first place among the masterworks of modern art. Otto Dix, however, remains a figure of secondary importance—an artist who invested the whole weight of his talent in the facile distortions of caricature. There is in Dix’s oeuvre a coarseness and vulgarity that denote a second-rate mind.

We’re given glimpses of these differences in the first room of the exhibition at the Neue Galerie, where a few paintings by Dix and Beckmann are installed. Among them are two self-portraits by Beckmann, Self-Portrait in Front of Red Curtain (1923) and Self-Portrait with Horn (1938), both of which address us as icons of unassailable self-possession: They command respect not only as aesthetic achievements but as documents of human nature. The paintings by Dix are also portraits. One of them is a picture of a semi-nude woman that’s yet another reminder of Dix’s innate vulgarity; the others are all exercises in pictorial caricature. For this viewer, anyway, the effect is to close the door on Otto Dix forever.