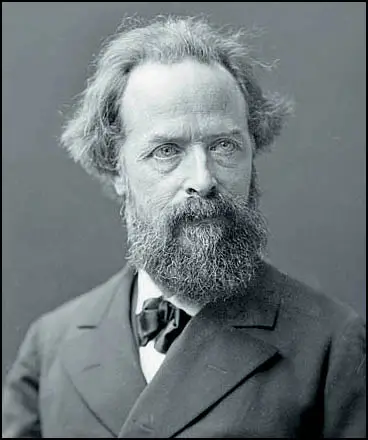

Élisée Reclus

Élisée Reclus, the son of Jacques Reclus, a Protestant pastor, was born at Sainte-Foy-la-Grande on 15th March, 1830. He had thirteen brothers and sisters. A talented student he went to the Protestant College of Sainte-Foy, before studying theology at Montauban. As a student he was a supporter of the French Revolution in 1848.

Reclus also studied in Strasbourg before moving to the University of Berlin in 1851 where he attended several lectures by the noted geographer Carl Ritter. He returned to Paris and protested against the coup d'état of Napoleon III. In 1852 he was forced to flee to London. According to Peter Kropotkin: "He lived in Ireland, where he espoused with all his ardour the cause of the Irish people, starved by the English, who had robbed them of their land and killed their rural industries."

In 1853 Élisée Reclus found work as a private tutor near New Orleans. He also published an account of his travels on the Mississippi River. During this period he became a strong opponent of slavery. He described Louisiana: "It is a great auction hall where everything is sold, slaves and owner into the bargain, votes and honour, the Bible and consciences. Everything belongs to the one who is richer."

On 14th December 1858, Reclus married Clarisse Brian of Sainte-Foy-la-Grande, daughter of a French sea captain and a Senegalese woman. Over the next few years he spent a great deal of time travelling, conducting research for a number of travel guides produced by the publishing firm Hachette. Reclus also spent time reading the work of anarchist writers and was a member of the International Brotherhood of Michael Bakunin and the League of Peace and Freedom. In 1864, Elisée helped to establish the first cooperative in Paris. In 1865 he joined the International Workingmen's Association. Other members included Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, Mikhail Bakunin and William Greene.

Peter Kropotkin pointed out: "Elisée answered to this double current, humanitarian and scientific. He contrived to interest the French in the great slavery abolition struggle which then began in America. He threw himself into the anti-imperial movement which was outlining itself in France, in the sixties, and he took part in the conspiracies of the time against the Empire. But a new movement was already beginning - the rousing of the French poorer classes, which was to stir the workingmen of the two hemispheres, and Elisée participated in the birth of this movement. From 1865 on, he had already belonged to the International Workingmen's Association; he identified himself with this movement from the time of the first meetings by which it was formed in 1864; and long before the Alliance of Bakunin was founded Elisée already belonged to the secret association also founded by Bakunin in Italy in 1864; and known as the International Fraternity, an association dissolved in 1869. In fact Elisée was a Communist long before the foundation of the International."

During the Siege of Paris (1870–1871) Reclus served in the National Guard. During this period he published articles in support of the Paris Commune. He was arrested on 5th April, 1871. Found guilty of offences against the government, in November he was sentenced to be deported to New Caledonia for life. After international pressure, from scientists such as Charles Darwin and Alfred Russell Wallace, this was changed in January 1872 to perpetual banishment from France.

Reclus moved to Geneva where he developed his ideas on anarchism: "The community of workers, have they the right to a partial re-appropriation of the collective produce? Without a doubt. When the revolution can't be made in its entirety, it must be made at least to the best of its ability. The isolation individual, has he a right to a personal re-appropriation of his part of the collective property? How can it be doubted? The collective property being appropriated by a few, why shouldn't it be taken back in detail, when it can't be taken back as a whole? He has the absolute right to take it - to steal, as it's said in the vernacular." Reclus once wrote; "As long as social injustice lasts we shall remain in a state of permanent revolution."

Élisée Reclus was not a supporter of the campaign to obtain the vote: "To vote is to abdicate. To name one or several masters for a short or long period means renouncing one’s own sovereignty. Whether he becomes absolute monarch, constitutional prince or a simple elected representative bearing a small portion of royalty, the candidate you raise to the throne or the chair will be your superior. You name men who are above laws, since they write them and their mission is to make you obey. To vote means being a dupe. It means believing that at the ringing of a bell men like you will suddenly acquire the virtue of knowing and understanding everything. Your elected representatives having to legislate on everything, from matches to warships, from the pruning of trees to the extermination of red or black villages, it seems to you that their intelligence grows thanks to the immensity of the task."

According to Samuel Stephenson, while living in Switzerland: "Reclus plunged into the writing of a 19-volume geographical work covering the whole world, entitled Nouvelle géographie universelle. It was finally completed and published in 1894. As an interesting side-note, Reclus is purported to have initiated the "Anti-marriage movement" from his residence in Geneva in 1882. After the publication of the Nouvelle géographie universelle, Reclus moved to Brussels, Belgium where he took up a job as professor of comparative geography at the New University of Brussels. Reclus also engaged in lecture tours, attending the Edinburgh Summer Meetings of 1893 and 1895, among others."

Havelock Ellis pointed out: "Élisée Reclus was one of the first to show that savage beliefs and customs, however outrageous or fantastic they may appear from the civilized point of view, have a demonstrable reasonableness and a justifiable morality when studied in connection with their environment. His scientific methods do not quite satisfy the more exact requirements which are now made in this branch of science, but the spirit and attitude of his work is that which now marks all research having as its end the unravelling of the savage mind. From the literary side the defects of strict method in Élisée Reclus's ethnographic work were a distinct advantage. He was not only a scholar and a man of science, but also something of an artist. His literary style was admirable. He loved the rich and expressive language of the sixteenth century, and his writings show how profitably a modern man may enrich his vocabulary by a judicious study of Montaigne and the other great masters of that age."

Anne Cobden-Sanderson compared his work to the achievements of William Morris and Peter Kropotkin: "They saw the world as it is today with all its injustice and cruelty, its want of harmony and beauty, but they never lost the vision of what the world might be, when humanity would rise in freedom to the moral and spiritual heights, which existing conditions now make unattainable. Elisée Reclus had the strength of character, the power of endurance and the vision of a Prophet of old. He came to us in London anxious to find support for the lately established New University at Brussels, but the idea which such a University represented, received little support in England where people are satisfied to continue on old conservative lines, leaving it for progressive thinkers to work alone on independent lines. Elisée Reclus' sympathy extended to the animal world, and he was and remained a convinced and practicing vegetarian."

Primary Sources

(1) Élisée Reclus, Le Révolté (11th October,1885)

You ask a man of good will, who is neither a voter nor a candidate, to reveal his ideas on the exercising of the right to suffrage.

You haven’t given me much time to answer, but since I have quite clear convictions on the subject of the electoral vote, what I have to say to you can be formulated in a few words.

To vote is to abdicate. To name one or several masters for a short or long period means renouncing one’s own sovereignty. Whether he becomes absolute monarch, constitutional prince or a simple elected representative bearing a small portion of royalty, the candidate you raise to the throne or the chair will be your superior. You name men who are above laws, since they write them and their mission is to make you obey.

To vote means being a dupe. It means believing that at the ringing of a bell men like you will suddenly acquire the virtue of knowing and understanding everything. Your elected representatives having to legislate on everything, from matches to warships, from the pruning of trees to the extermination of red or black villages, it seems to you that their intelligence grows thanks to the immensity of the task. History teaches you that that the contrary is the case. Power has always made mad, and speechifying makes stupid. It is inevitable that mediocrity prevails in sovereign assemblies.

To vote means evoking treason. Voters doubtless believe in the honesty of those to whom they grant their votes, and they are perhaps right the first day, when the candidates are still in the throes of their first love. But every day has its tomorrow. As soon as the setting changes, men change with it. Today the candidate bows before you, and perhaps too deeply. Tomorrow he will stand upright, and perhaps too tall. He begged for votes and he will give you orders. When a worker becomes a supervisor can he remain what he was before obtaining the boss’ favor? Doesn’t the fiery democrat learn to bow his head when the banker deigns to invite him to his office, when the king’s valets do him the honor of conversing with him in the antechambers? The atmosphere of these legislative bodies is unhealthy: you are sending your representatives into a corrupting milieu. Don’t be surprised that they leave it corrupted.

So don’t abdicate, don’t place your fate in the hands of men who are necessarily lacking in capability and future traitors. Don’t vote! Instead of trusting your interests to others, defend them yourselves. Instead of hiring lawyers to propose a future mode of action, act! Occasions aren’t lacking for men of good will. To place upon others the responsibility for one’s own conduct means to be lacking in valor.

(2) Peter Kropotkin, Élisée Reclus (1927)

Elisée answered to this double current, humanitarian and scientific. He contrived to interest the French in the great slavery abolition struggle which then began in America. He threw himself into the anti-imperial movement which was outlining itself in France, in the sixties, and he took part in the conspiracies of the time against the Empire. But a new movement was already beginning - the rousing of the French poorer classes, which was to stir the workingmen of the two hemispheres, and Elisée participated in the birth of this movement. From 1865 on, he had already belonged to the International Workingmen's Association; he identified himself with this movement from the time of the first meetings by which it was formed in 1864; and long before the Alliance of Bakunin was founded Elisée already belonged to the secret association also founded by Bakunin in Italy in 1864; and known as the International Fraternity, an association dissolved in 1869. In fact Elisée was a Communist long before the foundation of the International (his brother Elie, a convinced Fourierist, published a Fourierist paper during the Empire,) and the great Association of Working Men did nothing beyond offering to the French Communists a new international field of action. Towards the end of the Empire Elisée was in Paris, and had his monumental work, The Earth, published in 1867-68; the first volume of this work, The Continents, placed him immediately in the foremost rank of geographers of our time. Like everything which Elisée has written, this is a work of remarkable beauty. From the be inning to the end the manner of explaining the general ideas, or of describing certain features of Nature, has a force,a beauty, and a gracefulness which, with the exception of Alexander von Humboldt, has no equal in the whole literature of the century. I was telling him once how I was struck in Madrid, as I deeply enjoyed the works of Murillo, with this idea 'Why does the beautiful live for centuries?" "The beautiful?" Elisée replied, "but that is an idea thought out in detail." And since then, every time that I read a page of his, I remembered this definition. Murillo's Madonna would not be beautiful were it not that every detail her hands, her hair, down to the folds of her garment, harmonized with the fundamental idea of the picture the ecstasy of pure love. In the same way a page by Elisée would lose its beauty if the fundamental idea were not so well thought out in its details, that every detail, every secondary idea, comes to frame, to enforce the original idea of a given page, chapter, pamphlet or book.