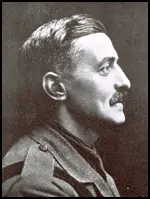

Wilfred Sheridan

Wilfred Sheridan, the son of Algernon Thomas Sheridan and Mary Motley Sheridan, was born in 1879. Wilfred was the great grandson of Richard Brinsley Sheridan, The family lived at the 18th century Frampton Court near Dorchester. According to Alan Chedzoy: "It was Algernon Thomas Brinsley who inherited the estate because, although only the sixth born, he had outlived his brothers. He was not a cultivated man like his father. An ex-naval officer, he occupied himself with shooting, fishing, and cricket... Not a careful steward of either the estate or the family money, Algernon was soon making ends meet by selling off outlying cottages, and even valuable Sheridan manuscripts from the library."

Sheridan found work as a stockbroker in London. In 1903 Sheridan fell in love with Clare Frewen, the seventeen year old daughter of Moreton Frewen and Clarita Jerome. Frewen had financial difficulties and wanted her to marry someone with more money. Sheridan's parents also wanted him to find someone with inherited wealth. Clare was determined to marry Sheridan. She told Anita Leslie that "in Wilfred's company she felt herself utterly natural, sparkling and gay". Clare later recalled in her autobiography, Naked Truth (1927): "The fact was that not only did I care for Wilfred, but I was paralysed by the general attitude of society towards elder sons. I could not bring myself, however charming they might be (and who shall say that elder sons cannot be charming?) to talk to them without self-consciousness... I could not get rid of the sensation that they knew that I was poor and that I knew they were marriageably desirable. I could not bear that they should think, or that anyone looking on should think, that I made the slightest effort to be unduly amiable."

1910 Sheridan once again approached Moreton Frewen about marrying Clare. Both sets of parents were against the marriage. According to Anita Leslie, the author of Clare Sheridan (1976): "Wilfred was a great gentleman, he came of the crispest upper crust of the English country aristocracy, he had literary talent in his family, he was often referred to as the best-looking man of his time - scholarly, athletic, a man whom other men admired and respected and who attracted every woman he met. Wilfred's parents did not hide their bitter disappointment. How could the handsome Sheridan heir choose to marry an absolutely penniless girl? It meant he would have to continue earning in the City so that his sons could go to the right schools. Later he would inherit Frampton Court and live quietly in Dorsetshire. He would have books and horses and an estate of 6000 acres to run, but no town house, no travel, no worldly luxuries. Clare and Wilfred had waited so long while elders explained the impossibility of such a match: now they wondered why they had wasted time."

Frewen reluctantly agreed and the proposed marriage was announced in July, 1910. Clare received a letter of support from Henry James: "I give you together what I venture to call a fond benediction, and verily shade my eyes a little before the dazzle of your combined personal lustre". Rudyard Kipling wrote a letter where he suggested that she should now reconsider her attempts to become a writer: "I should chuck poetry and literature if I were you. They don't make for married happiness on the she-side." The couple were married on 15th October 1910. Herbert Henry Asquith, the Prime Minister, and four Cabinet ministers, attended the ceremony. Also there was Winston Churchill and his new bride, Clementine Hozier.

Until they inherited the family home Wilfred and Clare leased a small Tudor house called Mitchem on the estate of his friend William St John Brodrick, 1st Earl of Midleton. His father gave him an allowance of £1,000 that enabled him to employ five servants. Over the next five years Clare gave birth to three children, Margaret, Elizabeth and Richard. Elizabeth unfortunately died of tuberculosis in 1914.

Alan Chedzoy has written: "Wilfred Sheridan, the surviving second son, was now the hope of the Sheridans. Unfortunately, however, his successful city career was ruined when his firm failed... in 1914". On the outbreak of the First World War, Wilfred Sheridan, now aged 35, was desperate to join the British Army. With the help of friends he managed to become a Lieutenant in the Rifle Brigade. He was sent to the Western Front in May, 1915. Clare wrote to a friend: "Black Puss (Wilfred) went to France yesterday - I feel as if if it were the end of the world. I can hardly hold my head up. Didn't know one could live through such hell."

In August 1915, Sheridan spent two weeks on leave at Frampton Court. When it was time to return he insisted they said good-bye at the gate: "I don't want you to come to the station. A station is not a place for good-byes." According to Anita Leslie: "So they parted amidst the green trees. She stood there watching him walk away - so light of step, sunburned and handsome. Once he turned to wave. Then he was gone."

Wilfred Sheridan was killed at the Battle of Loos on 25th September, 1915. A fellow officer wrote to Clare Sheridan about the attack on the German trenches: "We made an attack on Saturday morning at 4.30. I was in the German trench with Mr. Wilfred and another officer. We were going around the trench when a German met us, shot the officer, wounded me and Mr. Wilfred shot him down before going on to the 2nd line leading his Bombers fine. He did not seem to care in the least, he simply went on at the head of them into the Trenches. He was alive and well when I was carried back." Soon afterwards Sheridan was killed by a German sniper.

Soon afterwards Clare Sheridan found a letter written by her husband: "You will only read this if I am dead, and remember that as you read it I shall be by your side. Remember that all over England are broken hearts and ruined lives, remember that one splendid woman, such as you are, refusing to weep, and hugging her soul with pride at a soldier's death, will consciously or unconsciously stiffen up and bring comfort to these... God keep you and help you and bring my little Margaret up happily. I can leave you nothing, darling, except the memory of years, and you know what our life together has been. Surely if perfection is attained we have attained it."

Primary Sources

(1) Anita Leslie, Clare Sheridan (1976)

Wilfred Sheridan was a great gentleman, he came of the crispest upper crust of the English country aristocracy, he had literary talent in his family, he was often referred to as the best-looking man of his time - scholarly, athletic, a man whom other men admired and respected and who attracted every woman he met. Wilfred's parents did not hide their bitter disappointment. How could the handsome Sheridan heir choose to marry an absolutely penniless girl? It meant he would have to continue earning in the City so that his sons could go to the right schools. Later he would inherit Frampton Court and live quietly in Dorsetshire. He would have books and horses and an estate of 6000 acres to run, but no town house, no travel, no worldly luxuries. Clare and Wilfred had waited so long while elders explained the impossibility of such a match: now they wondered why they had wasted time.

(2) Wilfred Sheridan, letter to Clare Sheridan (August 1915)

You will only read this if I am dead, and remember that as you read it I shall be by your side . Remember that all over England are broken hearts and ruined lives, remember that one splendid woman, such as you are, refusing to weep, and hugging her soul with pride at a soldier's death, will consciously or unconsciously stiffen up and bring comfort to these... God keep you and help you and bring my little Margaret up happily. I can leave you nothing, darling, except the memory of years, and you know what our life together has been. Surely if perfection is attained we have attained it.

(3) Henry James, letter to Clare Sheridan (October, 1915)

The thought of coming into your presence and into Mrs. Sheridan's with such empty and helpless hands is in itself paralysing; and yet even so I say that, the sense of my whole soul is full, even to its being racked and torn, of Wilfred's belovedest image and the splendour and devotion in which he is all radiantly enwrapped and enshrined, makes me ask myself if I don't really bring you something of a sort, in thus giving you the assurance of how absolutely I adored him! Yet who can give you anything that approaches your incomparable sense that he was yours, and you his, to the last possessed and possessing radiance of him.