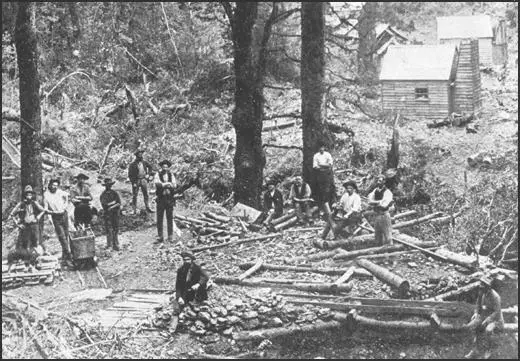

Gold miners in the Black Hills of Dakota

In 1874 General George A. Custer led an expedition to the Black Hills of Dakota. He reported that he discovered gold in the area. The following year the United States government attempted to buy the Black Hills for six million dollars. The area was considered sacred by the Sioux and they refused to sell. Custer's story attracted gold hunters and in April 1876 the mining town of Deadwood was established in the area. This provoked the Sioux and resulted in the war that led to the battle of Little Bighorn.

Primary and Secondary Sources

(1) Nelson Miles, Personal Recollections and Observations (1896)

The cause of the Indian War of 1876-77 in the Northwest may be briefly stated. That country originally belonged to the great Crow Tribe of friendly Indians. The Sioux Indians drifted from the region of the Great Lakes, and as they were driven west, in turn, they drove the Crows back to the mountains. The Sioux, or cutthroats, as they were called, finally

took the name of the Dakota Nation, made up principally of Uncapapas, Ogalallas, Minneconjoux, Sans Arcs, and Brules. Also affiliated with them were the Cheyennes, Yanktonais, Tetons, Santees, and Assiniboins. They claimed the whole of that northwest country, what is now North and South Dakota, northern Nebraska, eastern Wyoming, and eastern Montana.

In 1869 the government, in consideration of the Indians giving up a large part of their country, granted them large reservations, known as the Spotted Tail and Red Cloud agencies, and other reservations west of the Missouri. It also allowed them a large range of country as hunting-grounds, and, in addition, agreed to give them stated annuities. It was distinctly understood that the government would keep white people from occupying or trespassing upon the lands granted to the Indians. In the main, the Indians adhered to the conditions of the treaty, but unfortunately the government could not, or did not, comply with its part of the compact. Between the years 1869-75 the pressure of advancing civilization was very great upon all sides. The hunters, prospectors, miners, and settlers were trespassing upon the lands granted to the Indians.

It was generally believed that the Black Hills country possessed rich mineral deposits, and miners were permitted to prospect for mines. Surveying parties were allowed to traverse the country for routes upon which to construct railways, and even the government sent exploring expeditions into the Black Hills country, that reported evidences of gold fields. All this created great excitement on the part of the white people and a strong desire to occupy that country. At the same time it exasperated the Indians to an intense degree, until disaffection developed into open hostilities.

(2) General George Crook, Autobiography (1889)

The discovery of gold in the Black Hills was attracting much attention amongst the people of the country. Many expeditions were being fitted out with the view of going into that country. As it was on the Sioux reservation, the authorities in Washington were anxious to prevent this violation of the treaty stipulations. Several parties were prevented from going in. General Sheridan, in command of the Division of the Missouri, issued an order directing the troops to arrest any such persons attempting to go into the Black Hills and to destroy all their transportation, guns, and property generally. But notwithstanding all these precautions, many had sifted in. I was ordered to proceed to that country and eject these people.

(3) John F. Finerty, Warpath and Bivouac (1890)

The white man's government might make what treaties it pleased with the Indians, but it was quite a different matter to get the white man himself to respect the official parchment. Three-fourths of the Black Hills region and all of the Big Horn were barred by the Great Father and Sitting Bull against the enterprise of the daring, restless and acquisitive Caucasian race. The military expeditions under Generals Sully, Connor, Stanley and Custer, all of which were partially unsuccessful, had attracted the attention of the country to the great region already specified. The beauty and variety of the landscape; the immense quantities of the noblest species of American game; the serrated mountains and forest-covered hills; the fine grazing lands and rushing streams, born of the snows of the majestic Big Horn peaks; and, above all else, the rumor of great gold deposits, the dream of wealth which hurled Cortez on Mexico and Pizarro on Peru, fired the Caucasian heart with the spirit of adventure and exploration, to which the attendant and well-recognized danger lent an additional zest.

The expedition of General Ouster, which entered the Black Hills proper - those of Dakota - in 1874, confirmed the reports of gold finds, and thereafter a wall of fire, not to mention a wall of Indians, could not stop the encroachments of that terrible white race before which all other races of mankind, from Thibet to Hindostan and from Algiers to Zululand, have gone down. At the news of gold the grizzled '49s' shook the dust of California from his feet and started overland, accompanied by daring comrades, for the far-distant Hills; the Australian miner left his pick half buried in the antipodean sands and started, by ship and saddle, for the same goal; the diamond hunter of Brazil and of the Cape; the veteran prospectors of Colorado and western Montana; the Tar Heels of the Carolina hills; the reduced gentlemen of Europe; the worried and worn city clerks of London, Liverpool, New York, or Chicago; the stout English yeoman, tired of high rents and poor returns; the sturdy Scotchman, tempted from stubborn plodding after wealth to seek fortune under more rapid conditions; the light-hearted Irishman, who drinks in the spirit of adventure with his mother's milk; the daring mine delvers of Wales and of Cornwall; the precarious gambler of Monte Carlo - in short, every man who lacked fortune, and who would rather be scalped than remain poor, saw in the vision of the Black Hills, El Dorado.

(4) Chief Joseph, An Indian's Views of Indian Affairs, North American Review (April, 1879)

My friends, I have been asked to show you my heart. I am glad to have a chance to do so. I want the white people to understand my people. Some of you think an Indian is like a wild animal. This is a great mistake. I will tell you all about our people, and then you can judge whether an Indian is a man or not. I believe much trouble and blood would be saved if we opened our hearts more. I will tell you in my way how the Indian sees things. The white man has more words to tell you how they look to him, but it does not require many words to speak the truth. What I have to say will come from my heart, and I will speak with a straight tongue. Ah-cum-kin-i-ma-me-hut (the Great Spirit) is looking at me, and will hear me...

The first white men of your people who came to our country were named Lewis and Clarke. They also brought many things that our people had never seen. They talked straight, and our people gave them a great feast, as a proof that their hearts were friendly. These men were very kind. They made presents to our chiefs and our people made presents to them. We had a great many horses, of which we gave them what they needed, and they gave us guns and tobacco in return. All the Nez Perces made friends with Lewis and Clarke, and agreed to let them pass through their country, and never to make war on white men. This promise the Nez Perces have never broken...

For a short time we lived quietly. But this could not last. White men had found gold in the mountains around the land of winding water. They stole a great many horses from us, and we could not get them back because we were Indians. The white men told lies for each other. They drove off a great many of our cattle. Some white men branded our young cattle so they could claim them. We had no friend who would plead our cause before the law councils. It seemed to me that some of the white men in Wallowa were doing these things on purpose to get up a war. They knew that we were not strong enough to fight them. I labored hard to avoid trouble and bloodshed. We gave up some of our country to the white men, thinking that then we could have peace. We were mistaken. The white man would not let us alone. We could have avenged our wrongs many times, but we did not. Whenever the Government has asked us to help them against other Indians, we have never refused. When the white men were few and we were strong we could have killed them all off, but the Nez Perces wished to live at peace.