Sue Ryder

Susan Ryder was born in Leeds on 3rd July, 1924. Her father, Charles Foster Ryder, was a gentleman landowner with estates in Yorkshire and East Anglia. He had five children from his first marriage. Sue's mother, Mabel Sims, was his second wife. Richard K. Morris has pointed out: "Mabel was a warm-hearted mother who read aloud to her children, wrote them stories, invented games, played songs for them to sing and encouraged their interests.... A tireless worker for scores of causes, she was one of life's givers."

Susan Ryder was educated at home (the family had houses in Scarcroft and Great Thurlow). She later wrote: "We lived in Scarcroft near Leeds and, until the early thirties, for four months of the year at Thurlow in Suffolk. Though Scarcroft was village on the main Leeds-Wetherby road, our pleasant home was almost within walking distance of terrible slums. As a child I visited that people living there, and the children would come over to us for outings and to play in our fields and garden. I remember preparing food and bags of sweets for them, and enjoyed joining in the excitement of their outings away from the back-to-back houses and narrow cobbled streets - the only places they had to play. The bad housing conditions appalled me. It was usual to find only one bedroom in a house, which meant that the children had to sleep with their parents and sometimes a sick person too. Several children would share the same bed. The dreariness of their surroundings, with no lavatory, often no water tap, little to eat and frequently no change of clothes or shoes horrified me."

Her biographer, Mark Pottle, has pointed out: "Religion was central to her upbringing and she learned from her mother especially the value of Christian compassion. A short distance from the comfortable family home at Scarcroft were terrible slum dwellings, where her mother undertook social work. Accompanying her on visits there the young Sue Ryder witnessed poverty at first hand and was shocked by what she saw."

Charles Ryder was a well-educated man who had a deep interest in history and literature. At an early age he talked to his daughter about the latest novels of Aldous Huxley and H. G. Wells. Like his wife he had progressive political opinions and championed the rights of small nations. He had been particularly concerned about the rise of Benito Mussolini, Adolf Hitler and Francisco Franco.

Susan Ryder was educated at home (the family had houses in Scarcroft and Great Thurlow). This included studying the poetry of Julian Grenfell, Rupert Brooke, Siegfried Sassoon, and Wilfred Owen. She was also given a practical education. From the age of eight she was encouraged to work in the dairy, scrubbing its flagstones, dispensing milk to villagers, butter-making and assisting the delivery of calves. She was also taught to drive a tractor.

Susan completed her education at Benenden School. One of her friends at school was a Jewish refugee from Italy. She wrote to her mother: "She tells me in graphic detail about the arrests, suspicions and the Fascists. Her family only just got out in time, thousands were left. Many won't realize or believe the fate which awaits them. Equally, the majority of people don't understand the full horror of what is happening and being planned... If one didn't believe in God and justice in the next world, one might despair."

On the outbreak of the Second World War, she was too young at sixteen to enlist in anything. In 1940 she joined the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry. Soon afterwards she went to work for the Special Operations Executive. According to her biographer, Mark Pottle: "Her duties included driving the agents to airfields from which they would be flown into occupied Europe. Their bravery left an indelible mark upon her and she searched for some way of perpetuating the qualities that they represented."

In 1942 Susan Ryder married a young naval officer who was killed in action soon afterwards. In the following year she was sent overseas with the SOE, first to North Africa and then to Italy. At the end of the war she became a member of the Amis des Volontaires Français and worked with other relief units in Europe. In Germany she worked with those who had been arrested by the Allies in the aftermath of the war. Richard K. Morris has argued: "Bewildered survivors of concentration camps and forced labour were at large in the countryside, foraging for food and raiding farms. Some developed entrepreneurial skills in the black market. Girls sold themselves. A few hunted down their former persecutors."

The Allied forces of occupation dealt harshly with those who broke the law and large numbers were sentenced to lengthy spells in prison. Susan Ryder became their advocate: "By 1950 there were 1,400 of them.... She drove thousands of miles a year to visit them, challenged their indictments, pored over legal texts and pleaded for them in courts, sat with them around their night-fires amid the rubble of shattered cities, brought them books and food, pestered Allied officers for the commutation of their sentences, found new homes for them in other parts of the world, smuggled victims from zone to zone and pleaded their cause to anyone who would listen." According to Mark Pottle: "Ryder worked wherever she perceived the need, and was instinctively drawn to the neglected. In German prisons she found many non-Germans harshly sentenced by military courts for crimes ranging from petty theft to murder. Ryder took up the cause of these forgotten men, who were often the survivors of concentration camps, and fought doughtily against official obstruction to improve their conditions. She visited some 130 prisons regularly and also established, briefly, a holiday home in Denmark for concentration camp survivors and those with long-term illnesses."

In 1952 Sue Ryder established a home for this people in Bad Neuheim. Another one followed in Großburgwedel. "With the help of a small legacy, credit from the bank and much optimism" she established the Sue Ryder Foundation in 1953. According to its charter: "This is an international foundation devoted to the relief of suffering on the widest scale. It seeks to render personal service to those in need and to give affection to those who are unloved, regardless of age, race or creed, as part of the Family of man."

In 1955 Sue Ryder met Leonard Cheshire. As Richard K. Morris has pointed out: "Although their two charities differed in scope, there were concordances. Both had begun as spontaneous individual responses to immediate need, both were concerned with the relief of suffering, each laid paramount emphasis upon personal, voluntary sacrifice and each laid paramount emphasis upon personal, voluntary sacrifice and each had been fuelled by a Christian impulse."

The couple visited India in 1957. The following year they travelled to Germany together and discussed the possibility of some joint projects. In September 1958 they announced plans to open a home for the incurably ill in Poland, which would be run under a new Ryder-Cheshire Foundation. Cheshire later recalled: "We would have been happier still if our respective foundations.... had been able to merge. But they had each been in existence too long, each with their specific terms of reference and their own separate body of supporters, to make that possible."

The Foundation's aim was to take on projects which did not quite fall within the remit of either of their own larger foundations, Leonard Cheshire Disability and Sue Ryder Foundation. The first project was the Raphael Centre for lepers. Cheshire and Ryder had first encountered the lepers near Dehra Dun: "I am not quite sure how or by whom I was first told of the Dip, for one could well live in Dehra Dun half a lifetime and not really know that it existed. It was an unsavoury place on the south-western edge of the town that must once upon a time have been a largish quarry. An open drain ran through the middle of it and at the far end was a city refuse dump... From the road itself the Dip was out ofsight. Indeed one would have to walk up to its edge and peer into it before realizing that it contained a cluster of little mud houses with beaten-out milk-powder tins for roofing, and that a hundred or more people actually lived in them.... I shall never forget my first impression of this little community, barricaded, as it were, from the rest of the town and yet m essence dust another section of the city itself, whose inhabitants were owed the same rights and privileges as everybody else... the sheer poverty of the tiny houses in which they lived was not very different from other shanty towns I had seen... But somehow the combination of such a degree of poverty with the fact of being ostracized had the effect of creating a common solidarity. Certainly I was not prepared for the extraordinary and spontaneous warmth of their welcome."

Cheshire asked Sue Ryder to marry him. As she recalled in her autobiography, Child of my Love (1986), at first she had doubts about the idea: "The work had meant my life, and nothing I felt should or could change this. How in the future could one combine both marriage and work? Moreover, even in normal circumstances, marriage inevitably brings great responsibilities - I had always felt that it was a gamble. Furthermore, the implications are so serious that it is wiser to remain single and work than to run the risk of an unhappy marriage. Comparatively few people prepare themselves for or are equal to sharing literally everything." They were married on 5th April 1959.

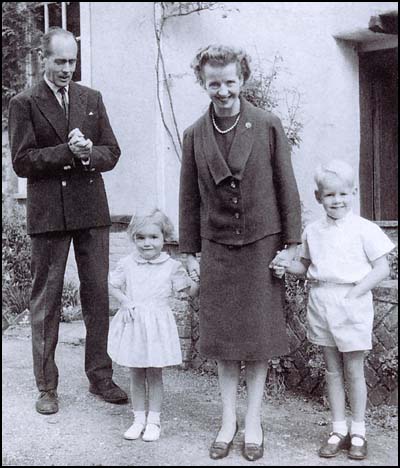

According to her biographer, Mark Pottle: "After an all too brief honeymoon in India they began their married life with an arduous joint fund-raising tour of Australia and New Zealand. Mother Teresa of Calcutta had once told them that they would find the sacrifices that marriage entailed worthwhile, and so it proved. Together they shared happiness, as well as the enormous demands placed upon them by their respective foundations, to which each was a willing martyr. On their return to Britain they lived in a small flat at Cavendish. A son and daughter were born in 1960 and 1962 but Ryder did not allow pregnancy to interrupt her work. She preferred action to delegation and was happiest when driving through the night to open a new home or deliver aid.... Small, thin, and neatly dressed, with characteristic headscarves, she seemed to have no interest in food... Her family background lent a grandeur to her manner that she never lost, in spite of the simplicity of her tastes and the frugality of her lifestyle. And behind the piety there was a lively character with a hint of flirtatiousness."

In 1975 Sue Ryder published an autobiography, And the Morrow is Theirs. Four years later she was created a life peer in recognition of being one of the greatest Christian charity workers of her time. Her title, Baroness Ryder of Warsaw, was a personal tribute to the people of Poland. She played an active and independent part in House of Lords debates. A second volume of autobiography, Child of my Love, was published in 1986.

Leonard Cheshire died in 1992. Sue Ryder continued her charity work and by this time the Sue Ryder Foundation ran 80 homes in a dozen countries, with 28 in Poland and 22 in Yugoslavia.She became a household name through a chain of about 500 high-street charity shops. However, as Mark Pottle points out: "Her last years were overshadowed by a bitter dispute with the trustees of the Sue Ryder Foundation over their plans to modernize the charity - a case of what some in the sector unkindly, if aptly, called ‘founder member syndrome’. The dispute caused great distress to Lady Ryder, and damage to the charity that she had created, and reached a sad conclusion in 1998 when Sue Ryder severed links with the Sue Ryder Foundation."

The Independent reported: "The Sue Ryder Foundation was established 47 years ago to help the homeless in the aftermath of the Second World War but it subsequently widened its appeal to include the sick and needy in Britain and had a string of health care homes and 500 charity shops. But in recent months she had become estranged from the organisation, which changed its name to Sue Ryder Care and dropped her traditional logo, a sprig of rosemary for remembrance, in favour of an image of a smiling sun. Lady Ryder was angered and before she went into hospital set up a new organisation to keep faith with her original principles of compassion and the relief of suffering." In September 2000, Sue Ryder established Sue Ryder Care.

Sue Ryder died after a lengthy illness at Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk, on 2nd November 2000.

Primary Sources

(1) Richard K. Morris, Cheshire (2000)

Bewildered survivors of concentration camps and forced labour were at large in the countryside, foraging for food and raiding farms. Some developed entrepreneurial skills in the black market. Girls sold themselves. A few hunted down their former persecutors...

By 1950 there were 1,400 of them.... She (Sue Ryder) drove thousands of miles a year to visit them, challenged their indictments, pored over legal texts and pleaded for them in courts, sat with them around their night-fires amid the rubble of shattered cities, brought them books and food, pestered Allied officers for the commutation of their sentences, found new homes for them in other parts of the world, smuggled victims from zone to zone and pleaded their cause to anyone who would listen.

(2) Leonard Cheshire, interview with Kevin Brownlow (21st August, 1991)

I am not quite sure how or by whom I was first told of the Dip, for one could well live in Dehra Dun half a lifetime and not really know that it existed. It was an unsavoury place on the south-western edge of the town that must once upon a time have been a largish quarry. An open drain ran through the middle of it and at the far end was a city refuse dump... From the road itself the Dip was out ofsight. Indeed one would have to walk up to its edge and peer into it before realizing that it contained a cluster of little mud houses with beaten-out milk-powder tins for roofing, and that a hundred or more people actually lived in them....

I shall never forget my first impression of this little community, barricaded, as it were, from the rest of the town and yet m essence dust another section of the city itself, whose inhabitants were owed the same rights and privileges as everybody else... the sheer poverty of the tiny houses in which they lived was not very different from other shanty towns I had seen... But somehow the combination of such a degree of poverty with the fact of being ostracized had the effect of creating a common solidarity. Certainly I was not prepared for the extraordinary and spontaneous warmth of their welcome.

(3) Laurence Shirley, letter to Richard K. Morris (28th December, 1996)

The Raphael hospital project started alright; we felled trees and cleared the site to start building. Marked out the position of the various wards and buildings... Then things started to slow. There was difficulty in obtaining construction drawings from the design engineers in England... A worse problem was lack of funds. For a time this brought the work to a halt.

It was decided to put the building materials on site to good use... a number ofsmall houses were put up to accommodate lepers who were outcasts and living on the city rubbish dump. The most difficult and distressing thing was to choose just two or three people at a time out of many to live in the houses we had built. People would hang on to us and our legs asking to be taken in. But we only had enough materials and money to build no more than six simple little houses.

(4) Sue Ryder, Child of my Love (1986)

The work had meant my life, and nothing I felt should or could change this. How in the future could one combine both marriage and work? Moreover, even in normal circumstances, marriage inevitably brings great responsibilities - I had always felt that it was a gamble. Furthermore, the implications are so serious that it is wiser to remain single and work than to run the risk of an unhappy marriage. Comparatively few people prepare themselves for or are equal to sharing literally everything.

(5) John Shaw, The Independent (3rd November, 2000)

The Sue Ryder Foundation was established 47 years ago to help the homeless in the aftermath of the Second World War but it subsequently widened its appeal to include the sick and needy in Britain and had a string of health care homes and 500 charity shops.

But in recent months she had become estranged from the organisation, which changed its name to Sue Ryder Care and dropped her traditional logo, a sprig of rosemary for remembrance, in favour of an image of a smiling sun. Lady Ryder was angered and before she went into hospital set up a new organisation to keep faith with her original principles of compassion and the relief of suffering.