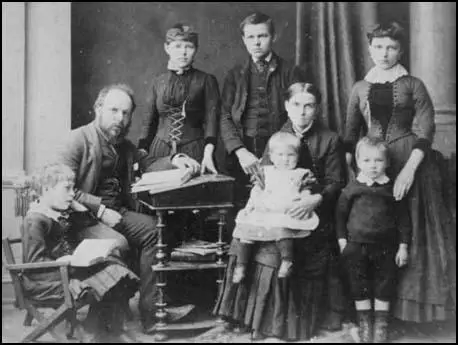

Edward Steer

Edward Steer, the son of Edward Steer, a builder and plumber (1820-1872) and Sarah Rich was born in East Hoathly on 22nd May, 1842. Edward's father moved to East Grinstead in 1856 where he opened an ironmonger shop in the High Street (now Broadleys). In 1890 Edward's father built Moat Congregational Church (now the United Reformed Church).

Edward was taught at Sunday School by Thomas Cramp, the leader of the East Grinstead Temperance Society. Eventually Edward and his three brothers, William, George and Walter, took the pledge and became members of the Band of Hope.

In 1863 Edward Steer married Anne Harding, the daughter of Thomas Harding, the owner of a grocery and drapers store in the High Street. For the next two years Steer was postmaster in Reigate. In 1865 he moved to Turners Hill where he was postmaster for seventeen years. Edward Steer remained a committed Nonconformist and in 1870 became secretary of the Congregational chapels at Copthorne, Turners Hill and West Hoathly. Steer also formed the Turners Hill Temperance Society.

Anne Steer gave birth to Alice in 1867. Over the next twenty years Edward and Annie had five more children: Constance, Charles, Emery, Florrie and Victor.

The Steer family moved back to East Grinstead in 1882. Later that year Steer established the Southern Free Press. The following year Steer began publishing the East Grinstead Times. Steer used the newspaper to promote his political and religious ideas. He became active in local politics and in 1884 failed to be elected to the Local Government Board. The following year, Steer organised C. J. Heald's unsuccessful attempt to become Liberal M.P. for East Grinstead.

Steer was a strong supporter of religious and political freedom. In 1887, a member of the Salvation Army was arrested and sent to prison for preaching sermons in the High Street. Steer organised a large demonstration against this decision and helped re-establish the right of citizens to hold public meetings in the streets of East Grinstead.

to right: Florrie, Alice, Charlie, Victor, Emery and Constance.

Attempts by Edward Steer to be elected to the council failed in 1888 and 1892. However, he was eventually successful in 1895. Steer was also elected as one one of the Nonconformist representatives on the East Grinstead School Board. He was also voted onto the Board of Guardians that had the task of administering the East Grinstead Workhouse.

Edward Steer sold the Southern Free Press in 1892 but he continued his interest in journalism and in 1899 wrote a series of articles for The East Grinstead Observer on his reminiscences of the town in the 1850s.

Although they described themselves as 'independents', the majority of men on the East Grinstead Urban Council were members of the Conservative Party. Edward Steer usually found himself in a minority when votes were taken at council meetings, although he did receive support from Dr. Thomas Hartigan and Joseph Rice who shared his radical political ideas. In 1900 Steer, Hartigan and Rice began their campaign to persuade the town to finance the building of council houses. These men also worked together in the proposal to buy Mount Noddy and to open it as a park for local children. At the time, most people in East Grinstead were hostile to the idea that rates should be used to pay for public parks and to provide cheap housing.

Edward Steer also became unpopular with ratepayers over his plans to reform the East Grinstead Workhouse. Steer's ideas included outdoor relief, an end to workhouse uniforms, more interesting and fulfilling work for the inmates, and the employment of trained nurses. Critics such as Charles Everard argued that Steer's proposed reforms would increase the cost of running the workhouse.

Steer received considerable support from Thomas Hartigan, the workhouse doctor. In 1901 Steer and Hartigan launched a bitter attack on the East Grinstead Board of Guardians. They accused some members of financial corruption. It was claimed that contracts were being placed with certain companies in return for cash payments. Steer and Hartigan could not sufficient evidence to support their claims and no actions were taken against board members. The Board of Guardians later forced Dr. Hartigan to resign his post and he left to become a surgeon at Blackfriars Hospital.

Edward Steer, like most Nonconformists, believed that the 1902 Education Act was an infringement of the principles of religious inequality. Steer saw the act as the State helping the Anglican Church to indoctrinate Britain's children. East Grinstead formed a Passive Resistance Movement and several of the leading figures in the town refused to pay the 'education rate'. Joseph Rice, G. H. Broadley, Stuart Johnson Reid, Ernest Young, William Young, Rev. James Campbell, Rev. James Dickerson Davies, Arthur True, James Morris, John Dalzeil and Alfred Burt had property seized as a result of their refusual to pay their full parish-rate. However, this was not possible in the case of Steer, who had transferred all his property over to his wife. As a result, in June 1904, Steer was arrested and sent to Lewes Prison.

In 1905 Steer and Joseph Rice were successful in persuading the East Grinstead Urban Council to purchase Mount Noddy. Edward Steer had also won the argument over subsidized housing and by 1905, the first twelve council houses had been built in Bellaggio Road. However, Steer was still in a minority on the council over the need for electric street lighting.

Steer's political belief in equality meant that he was also a supporter of votes for women. As a leading figure in East Grinstead's Liberal Party, Steer was a close friend of the Corbett family. Charles Corbett had campaigned for votes for women in the House of Commons. Marie Corbett and her two daughters, Margery Ashby and Cicely Fisher, were active in the Women's Suffrage Union.

In 1913 Edward Steer joined with Charles Corbett to help form the East Grinstead Men's League for Women's Suffrage. In July, 1913, Marie Corbett, asked Edward Steer, who was now chairman of the East Grinstead Urban Council, to speak at a meeting before the Women's Great Pilgrimage to London. The meeting in East Grinstead High Street was broken up by a hostile crowd of over 1,500 people.

This was not a new experience for Edward Steer, as a member of the Salvation Army and the Temperance Society, he had several times been attacked by unruly mobs. Even meetings held in support of the purchase of Mount Noddy and plans to subsidize council housing, had resulted in Steer being physically attacked by his political opponents.

Edward Steer was sixty-nine when war was declared in 1914. Still a member of the East Grinstead Urban Council, Steer became the town's Food Controller until the war ended in 1918. Steer served on the council until he was defeated in 1920.

Steer continued to stand in elections, and it was only after his third defeat in a row, that he became convinced he was no longer wanted. Now aged seventy-seven, Steer told the assembled crowd at the count: "I have served the town for 40 years and now I am going to retire." Edward Steer died on 23rd October, 1925 and was buried at the top of Mount Noddy, a place overlooking the park that he had fought so long and hard to obtain for the people of East Grinstead.

Primary Sources

(1) East Grinstead Observer (4th August, 1900)

Edward Steer, Chairman of the Housing of the Working Class Committee, proposed the building of cottages upon the vacant land belonging to the council at North End Pumping Station. Charles Rice said the working class in East Grinstead were in great need of cottages and he thought that the Council should do its utmost for the men. East Grinstead was overcrowded and if he had a hundred cottages he could easily let them.

(2) East Grinstead Observer (2nd February, 1901)

Mr. Steer said he hoped this scheme would be carried and he was sure if it was carried they would earn the gratitude of the town and its succeeding generations. The scheme would pay for itself in forty years, and after that time there would be £200 a year coming in reduction of rates. He thought their grandchildren would thank them for having done that. The surveyor estimated that at the Bellaggio site it would cost £180 per house; at North End it would cost £150 per house.

(3) East Grinstead Observer (28th May, 1904)

At Mr. Steer's home, when the seizure of goods was to be made, it was declared that the whole of the goods were the property of his wife. Mr. Steer was informed that the alternative to paying the amount owing in the event of their being no goods would be two days' imprisonment. Mr. Steer declared his intention of going to prison.

(4) East Grinstead Observer (6th January, 1900)

Edward Steer said it was an absolute necessity to have a recreation ground where men could go after the pressure, which was daily growing more and more, in their business life. A recreation ground was a necessity of life. Besides, they had adopted the Town Police Clauses Act by which they prevented children from playing in the streets, and it was not logical for them to do that and then provide no place for the children to play in.

(5) On 13th August, 1905, Edward Steer spoke at a public meeting on the need to buy Mount Noddy as a public park. On 19th August, The East Grinstead Observer published a letter by Thomas Isley on the meeting.

The reprehensive tactics of a few persons, apparently organised to deny the speakers a hearing, were much deplored by those, who, like myself, sought to hear the facts of the case. However, when something like order prevailed and Mr. Steer was granted a hearing. It is not given to many speakers to be able to withstand senseless booing and opposition and then to convince a very large majority of opponents, but, undoubtedly Mr. Steer was on Saturday night one of those exceptional men. I never witnessed a more remarkable instance, had had some of those who did not trouble to vote held up their hands the resolution would certainly be carried by a large majority.

(6) On 26th July 1913, The East Grinstead Observer reported a riot that had taken place in the town three days previously.

The main streets of East Grinstead were disgraced by some extraordinary proceedings on Tuesday evening. The non-militant section of the advocates of securing women’s suffrage had arranged a march and public meeting on its way to the great demonstration in London. The "procession" was not an imposing one. It consisted of about ten ladies who were members of the Suffrage Society. Mrs. Marie Corbett led the way carrying a silken banner bearing the arms of East Grinstead. The reception, which the little band of ladies got, was no means friendly. Yells and hooting greeted them throughout most of the entire march, and they were the targets for occasional pieces of turf, especially when they passed through Queen’s Road. In the High Street they found a crowd of about 1,500 people awaiting them.

Edward Steer had promised to act as chairman, and taking his stand against one of the trees on the slope he began by saying, "Ladies and Gentlemen". This was practically as far as he got with his speech. Immediately there was an outburst of yells and laughter and shouting. Laurence Housman, the famous writer, got no better than Mr. Steer. By this time pieces of turf and a few ripe tomatoes and highly seasoned eggs were flying about, and were not always received by the person they were intended for. The unsavoury odur of eggs was noticeable over a considerable area. Unhappily, Miss Helen Hoare of Charlwood Farm, was struck in the face with a missile and received a cut on the cheek and was taken away for treatment.

Some of the women were invited to take shelter in Mr. Allwork’s house, but as they entered the crowd rushed the doorway and forced themselves into the house. The police arrived and the ladies were taken out the back way and escorted them to the Dorset Arms Hotel, their headquarters, and this was for a long time besieged by a yelling mob…. Mrs. Marie Corbett slipped away and took up a position lower down the High Street on the steps of the drinking fountain. A young clergyman who appealed for fair play was roughly hustled and lost his hat. Mrs. Corbett had began to speak from the fountain steps but the crowd moved down the High Street and broke up her small meeting.