Women and the Anti-Slavery Movement

In 1824 Elizabeth Heyrick published her pamphlet Immediate not Gradual Abolition. In her pamphlet Heyrick argued passionately in favour of the immediate emancipation of the slaves in the British colonies. This differed from the official policy of the Anti-Slavery Society that believed in gradual abolition. She called this "the very masterpiece of satanic policy" and called for a boycott of the sugar produced on slave plantations. (1)

In the pamphlet Heyrick attacked the "slow, cautious, accommodating measures" of the leaders. "The perpetuation of slavery in our West India colonies is not an abstract question, to be settled between the government and the planters; it is one in which we are all implicated, we are all guilty of supporting and perpetuating slavery. The West Indian planter and the people of this country stand in the same moral relation to each other as the thief and receiver of stolen goods". (2)

Women and Anti-Slavery

The leadership of the organisation attempted to suppress information about the existence of this pamphlet and William Wilberforce gave out instructions for leaders of the movement not to speak at women's anti-slavery societies. His biographer, William Hague, claims that Wilberforce was unable to adjust to the idea of women becoming involved in politics "occurring as this did nearly a century before women would be given the vote in Britain". (3)

Although women were allowed to be members they were virtually excluded from its leadership. Wilberforce disliked to militancy of the women and wrote to Thomas Babington protesting that "for ladies to meet, to publish, to go from house to house stirring up petitions - these appear to me proceedings unsuited to the female character as delineated in Scripture". (4)

However, George Stephen disagreed with Wilberforce on this issue and claimed that their energy was vital in the success of the movement: "Ladies Associations did everything... They circulated publications; they procured the money to publish; they talked, coaxed and lectured: they got up public meetings and filled our halls and platforms when the day arrived; they carried round petitions and enforced the duty of signing them... In a word they formed the cement of the whole anti-slavery building - without their aid we never should have kept standing." (5)

Thomas Clarkson, another leader of the ant-slavery movement, was much more sympathetic towards women. Unusually for a man of his day, he believed women deserved a full education and a role in public life and admired the way the Quakers allowed women to speak in their meetings. Clarkson told Elizabeth Heyrick's friend, Lucy Townsend, that he objected to the fact that "women are still weighed in a different scale from men... If homage be paid to their beauty, very little is paid to their opinions." (6)

Records show that about ten per cent of the financial supporters of the organisation were women. In some areas, such as Manchester, women made up over a quarter of all subscribers. Lucy Townsend asked Thomas Clarkson how she could contribute in the fight against slavery. He replied that it would be a good idea to establish a women's anti-slavery society. (7)

Birmingham Ladies Society for the Relief of Negro Slaves

On 8th April, 1825, Lucy Townsend held a meeting at her home to discuss the issue of the role of women in the anti-slavery movement. Townsend, Elizabeth Heyrick, Mary Lloyd, Sarah Wedgwood, Sophia Sturge and the other women at the meeting decided to form the Birmingham Ladies Society for the Relief of Negro Slaves (later the group changed its name to the Female Society for Birmingham). (8) The group "promoted the sugar boycott, targeting shops as well as shoppers, visiting thousands of homes and distributing pamphlets, calling meetings and drawing petitions." (9)

The society which was, from its foundation, independent of both the national Anti-Slavery Society and of the local men's anti-slavery society. As Clare Midgley has pointed out: "It acted as the hub of a developing national network of female anti-slavery societies, rather than as a local auxiliary. It also had important international connections, and publicity on its activities in Benjamin Lundy's abolitionist periodical The Genius of Universal Emancipation influenced the formation of the first female anti-slavery societies in America". (10)

The formation of other independent women's groups soon followed the setting up of the Female Society for Birmingham. This included groups in Nottingham (Ann Taylor Gilbert), Sheffield (Mary Anne Rawson, Mary Roberts), Leicester (Elizabeth Heyrick, Susanna Watts), Glasgow (Jane Smeal), Norwich (Amelia Opie, Anna Gurney), London (Mary Anne Schimmelpenninck, Mary Foster), Darlington (Elizabeth Pease) and Chelmsford (Anne Knight). By 1831 there were seventy-three of these women's organisations campaigning against slavery. (11)

The Female Society for Birmingham played an important role in the propaganda campaign against slavery. Lucy Townsend, wrote the anti-slavery pamphlet To the Law and to the Testimony (1832). "Under Lucy Townsend's and Mary Lloyd's leadership the society developed the distinctive forms of female anti-slavery activity, involving an emphasis on the sufferings of women under slavery, systematic promotion of abstention from slave-grown sugar through door-to-door canvassing, and the production of innovative forms of propaganda, such as albums containing tracts, poems, and illustrations, embroidered anti-slavery workbags." (12)

In 1830, the Female Society for Birmingham submitted a resolution to the National Conference of the Anti-Slavery Society calling for the organisation to campaign for an immediate end to slavery in the British colonies. Elizabeth Heyrick, who was treasurer of the organisation suggested a new strategy to persuade the male leadership to change its mind on this issue. In April 1830 they decided that the group would only give their annual £50 donation to the national anti-slavery society only "when they are willing to give up the word 'gradual' in their title." At the national conference the following month, the Anti-Slavery Society agreed to drop the words "gradual abolition" from its title. It also agreed to support Female Society's plan for a new campaign to bring about immediate abolition. (13)

Sarah Wedgwood was an active member of the group. Her husband, Josiah Wedgwood had asked one of his craftsmen to design a seal for stamping the wax used to close envelopes. It showed a kneeling African in chains, lifting his hands and included the words: "Am I Not a Man and a Brother?" This image was "reproduced everywhere from books and leaflets to snuffboxes and cufflinks". (14)

Thomas Clarkson explained: "Some had them inlaid in gold on the lid of their snuff boxes. Of the ladies, several wore them in bracelets, and others had them fitted up in an ornamental manner as pins for their hair. At length the taste for wearing them became general, and this fashion, which usually confines itself to worthless things, was seen for once in the honourable office of promoting the cause of justice, humanity and freedom." (15)

Hundreds of these images were produced. Benjamin Franklin suggested that the image was "equal to that of the best written pamphlet".Men displayed them as shirt pins and coat buttons. Whereas women used the image in bracelets, brooches and ornamental hairpins. In this way, women could show their anti-slavery opinions at a time when they were denied the vote. Sophia Sturge, a member of the Female Society for Birmingham group were responsible for designing their own medal, "Am I Not a Slave And A Sister?" (16)

Richard Reddie has argued that during this period women such as Lucy Townsend emerged "out of the shadows" after the retirement of William Wilberforce, to play an important role in the anti-slavery campaign. These women "clearly identified with the plight of disenfranchised Africans" and claimed that "African women largely bore the brunt of abuses throughout chattel enslavement - rape and other violations were common occurrences on slave ships and plantations". (17) Vron Ware, explained in her book, Beyond the Pale: White Women, Racism and History (1992), that women's abolitionist women's literature was often quite explicit about the "indecencies" that women slaves endured. (18)

In early 1833 Anne Knight joined forces with the London Female Anti-Slavery Society to organise a national women's petition against slavery. When it was presented to Parliament it was signed by 298,785 women. It was the largest single anti-slavery petition in the movement's history. (19)

The Slavery Abolition Act was passed on 28th August 1833. This act gave all slaves in the British Empire their freedom. The British government paid £20 million in compensation to the slave owners. The amount that the plantation owners received depended on the number of slaves that they had. For example, Henry Phillpotts, the Bishop of Exeter, received £12,700 for the 665 slaves he owned. (20)

World Anti-Slavery Convention

Anne Knight attended the World Anti-Slavery Convention held at Exeter Hall in London, in June 1840 but as a woman was refused permission to speak. She did meet two American delegates Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott. Stanton later recalled: "We resolved to hold a convention as soon as we returned home, and form a society to advocate the rights of women." (21) Mott described Knight as "a singular-looking woman - very pleasant and polite". (22)

She became aware that the artist, Benjamin Robert Haydon, had started a group portrait of those involved in the fight against slavery. She wrote a letter to Lucy Townsend complaining about the lack of women in the painting. "I am very anxious that the historical picture now in the hand of Haydon should not be performed without the chief lady of the history being there in justice to history and posterity the person who established (women's anti-slavery groups). You have as much right to be there as Thomas Clarkson himself, nay perhaps more, his achievement was in the slave trade; thine was slavery itself the pervading movement." (23)

When the painting was completed it did not include Lucy Townsend or most of the leading female campaigners against slavery. Clare Midgley, the author of Women Against Slavery (1995) points out that as well as Anne Knight and Lucretia Mott, it does feature Elizabeth Pease, Mary Anne Rawson, Amelia Opie and Annabella Byron: "Haydon's group portrait is exceptional in that it does record the existence of women campaigners. Most other memorials did not. There are no public monuments to women activists to complement those to William Wilberforce, Thomas Clarkson and other male leaders of the movement... In the written memoirs of these men, women tend to appear as helpful and inspirational wives, mothers and daughters rather than as activists in their own right." (24)

showing from left to right, bottom row: Annabella Byron, Amelia Opie,

Mary Anne Rawson, top row, Anne Knight, Mrs John Beaumont and Elizabeth Pease.

Marion Reid published A Plea for Women in 1843. Knight was grateful that she had stated the case for greater equality but thought that the author had unestimated the abilities of women. Knight wrote on her own copy of the book that it was "excellent with the exception of the great folly" where she said that women faced natural barriers. Knight complained that women did not have natural barriers "but those placed equally before men." (25)

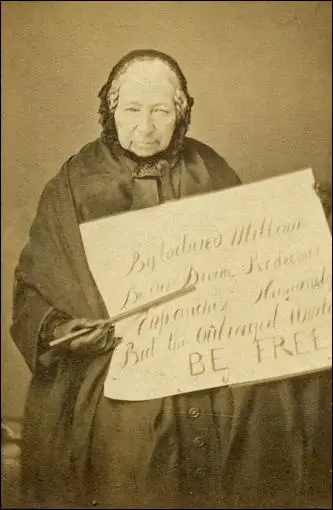

The behaviour of the male leaders at the World Anti-Slavery Convention inspired Anne Knight to start a campaign advocating equal rights for women. (26) This included having gummed labels printed with feminist quotations that she attached to the outside of her letters. In 1847 she wrote a letter to Matilda Ashurst Biggs on the subject of gender equality. Later that year the letter was published and it is considered to be the first ever leaflet on women's suffrage. (27)

Knight wrote: "I wish the talented philanthropists in England would come forward in this critical juncture of our nation's affairs and insist on the right of suffrage for all men and women unstained with crime... in order that all may have a voice in the affairs of their country... Never will the nations of the earth be well governed until both sexes, as well as all parties, are fully represented, and have an influence, a voice, and a hand in the enactment and administration of the laws." (28)

Women such as Anne Knight, Sophia Sturge, Elizabeth Pease and Elizabeth Pease, who had all been involved in the campaign against the slave trade, joined the Chartist movement. Sturge was active in Birmingham, that have a very strong group of women Chartists in the late 1830s. (29)

Anne Knight became concerned about the way women campaigners were treated by some of the male leaders in the organisation. She criticised them for claiming "that the class struggle took precedence over that for women's rights". (30) Knight wrote "can a man be free, if a woman be a slave." (31) In a letter published in the Brighton Herald in 1850 she demanded that the Chartists should campaign for what she described as "true universal suffrage". (32)

Knight argued: "Never will the nations of the earth be well governed, until both sexes, as well as all parties, are fully represented and have an influence, a voice, and a hand in the enactment and administration of the laws". (33) At a conference on world peace held in 1849, Anne Knight met two of Britain's reformers, Henry Brougham and Richard Cobden. She was disappointed by their lack of enthusiasm for women's rights. For the next few months she sent them several letters arguing the case for women's suffrage. In one letter to Cobden she argued that it was only when women had the vote that the electorate would be able to pressurize politicians into achieving world peace. (34)

Primary Sources

(1) William Wilberforce, letter to Thomas Babington (31st January, 1826)

For ladies to meet, to publish, to go from house to house stirring up petitions - these appear to me proceedings unsuited to the female character as delineated in Scripture. I fear its tendency would be to mix them in all the multiform warfare of political life.

(2) Elizabeth Heyrick, Immediate not Gradual Abolition (1824)

In the great question of emancipation, the interests of two parties are said to be involved, the interest of the slave and that of the planter. But it cannot for a moment be imagined that these two interests have an equal right to be consulted, without confounding all moral distinctions, all difference between real and pretended, between substantial and assumed claims. With the interest of the planters, the question of emancipation has (properly speaking) nothing to do. The right of the slave, and the interest of the planter, are distinct questions; they belong to separate departments, to different provinces of consideration. If the liberty of the slave can be secured not only without injury, but with advantage to the planter, so much the better, certainly; but still the liberation of the slave ought ever to be regarded as an independent object; and if it be deferred till the planter is sufficiently alive to his own interest to co-operate in the measure, we may for ever despair of its accomplishment. The cause of emancipation has been long and ably advocated. Reason and eloquence, persuasion and argument have been powerfully exerted; experiments have been fairly made, facts broadly stated in proof of the impolicy as well as iniquity of slavery, to little purpose; even the hope of its extinction, with the concurrence of the planter, or by any enactment of the colonial, or British legislature, is still seen in very remote perspective, so remote that the heart sickens at the cheerless prospect. All that zeal and talent could display in the way of argument, has been exerted in vain. All that an accumulated mass of indubitable evidence could effect in the way of conviction, has been brought to no effect.

It is high time, then, to resort to other measures, to ways and means more summary and effectual. Too much time has already been lost in declamation and argument, in petitions and remonstrances against British slavery. The cause of emancipation calls for something more decisive, more efficient than words. It calls upon the real friends of the poor degraded and oppressed African to bind themselves by a solemn engagement, an irrevocable vow, to participate no longer in the crime of keeping him in bondage...

The perpetuation of slavery in our West India colonies is not an abstract question, to be settled between the government and the planters; it is one in which we are all implicated, we are all guilty of supporting and perpetuating slavery. The West Indian planter and the people of this country stand in the same moral relation to each other as the thief and receiver of stolen goods.

The West Indian planters have occupied much too prominent a place in the discussion of this great question....The abolitionists have shown a great deal too much politeness and accommodation towards these gentlemen.... Why petition Parliament at all, to do that for us, which... we can do more speedily and effectually for ourselves?

(3) Sheffield Female Anti-Slavery Society, Appeal of the Friends of the Negro to the British People (1827)

Slavery is not exclusively a political, but pre-eminently a moral question; one, therefore, on which the humble-minded reader of the Bible, which enriches his cottage shelf, is immeasurably, a better politician than the statesman versed in the intrigues of Cabinets. We ought to obey God rather than man.

(4) Anne Knight wrote a letter to Lucy Townsend about the proposed painting by Benjamin Robert Haydon (20th September, 1840)

I am very anxious that the historical picture now in the hand of Haydon should not be performed without the chief lady of the history being there in justice to history and posterity the person who established (women's anti-slavery groups). You have as much right to be there as Thomas Clarkson himself, nay perhaps more, his achievement was in the slave trade; thine was slavery itself the pervading movement.

(5) Clare Midgley, Women Against Slavery (1995)

Haydon's group portrait is exceptional in that it does record the existence of women campaigners. Most other memorials did not. There are no public monuments to women activists to complement those to William Wilberforce, Thomas Clarkson and other male leaders of the movement... In the written memoirs of these men, women tend to appear as helpful and inspirational wives, mothers and daughters rather than as activists in their own right.

Student Activities

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)

The Luddites: 1775-1825 (Answer Commentary)

The Plight of the Handloom Weavers (Answer Commentary)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)