Denis Healey

Denis Healey, the son of an engineer, was born in Mottingham, on 30th August, 1917. Five years later his family moved to Keighley. When Healey was eight years old he won a scholarship to Bradford Grammar School. Influenced by the poetry of Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon from the First World War, Healey became a pacifist and in 1935 resigned from the school's Officer's training Corps.

In 1936 Healey entered Balliol College, Oxford. While at university he became active in politics. He became concerned about the emergence of Adolf Hitler. He rejected his earlier pacifism and joined the Communist Party.

Healey later explained in his autobiography, The Time of My Life, why he took this decision: "For the young in those days, politics was a world of simple choices. The enemy was Hitler with his concentration camps. The objective was to prevent a war by standing up to Hitler. Only the Communist Party seemed unambiguously against Hitler. The Chamberlain Government was for appeasement. Labour seemed torn between pacifism and a half-hearted support for collective security, and the Liberals did not count."

On the outbreak of the Second World War joined the British Army and he served with the Royal Engineers in North Africa, Sicily and Italy. This included being Military Landing Officer to the British assault brigade for Anzio. He admitted: "Unfashionable though it is to admit it, I enjoyed my five years in the wartime army. It was a life very different from anything I had known, or expected. Long periods of boredom were broken by short bursts of excitement. For the first time I had to learn to do nothing but wait - for me the most difficult lesson of all. To my great relief, I found I did not get frightened in action - not that I enjoyed being shelled or dive-bombed any more than the next man; but fear never paralysed me or even pushed me off my stroke. On the other hand I was never called on to show the sort of active courage which wins men the VC. A dumb, animal endurance is the sort of courage most men need in war. I was constantly amazed by the ability of the average soldier, and civilian, to exhibit this under stress." By the end of the war Healey had reached the rank of major.

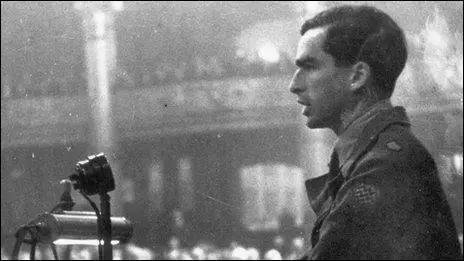

Healey left the Communist Party during the war and soon afterwards joined the Labour Party. He caught the attention of its leaders by making a speech at the 1945 Labour Party Conference: "The upper classes in every country are selfish, depraved, dissolute and decadent. The struggle for socialism in Europe ... has been hard, cruel, merciless and bloody. The penalty for participation in the liberation movement has been death for oneself, if caught, and, if not caught oneself, the burning of one's home and the death by torture of one's family ... Remember that one of the prices paid for our survival during the last five years has been the death by bombardment of countless thousands of innocent European men and women."

In the 1945 General Election he stood for Pudsey and Otley and was defeated by 1,651 votes. In November, 1945, Healey became secretary of the International Department of the Labour Party. In 1952 Healey was elected to the House of Commons. On the right of the party, Healey became an outspoken critic of Aneurin Bevan and his followers. In 1959 Hugh Gaitskell appointed Healey to the shadow cabinet.

When the Labour Party was elected in the 1964 General Election, Harold Wilson, the new prime minister, appointed Healey as his Secretary of State for Defence. Wilson later commented: "He (Healey) is a strange person. When he was at Oxford he was a communist. Then friends took him in hand, sent him to the Rand Corporation of America, where he was brainwashed and came back very right wing. But his method of thinking was still what it had been: in other words, the absolute certainty that he was right and everybody else was wrong, and not merely wrong through not knowing the proper answers, but wrong through malice. I had very little trouble with him on his own subject, but he has a very good quick brain and can be very rough. He probably intervened in Cabinet with absolute certainty about other departments more than any minister I have ever known, but he was a strong colleague and much respected."

His colleague, Ian Mikardo, has argued: "Denis Healey is an outstanding talent, equalled by very few people I've met in the whole of my long innings. When he speaks on international affairs, he speaks with the authority that derives from an unmatched knowledge of what's going on in almost every country in the world, and his analysis of all those movements of events is almost always penetrating and enlightening. He is a cultured man of parts, of many interests outside politics (those politicians whose lives contain nothing but politics are always second-class politicians). He's a bubbly, witty man who can be a charming and entertaining companion.

Over the next six years Healey attempted to preserve the country's defence commitments but he eventually had to accept defeat and began withdrawing Britain's armed forces from Aden and the Persian Gulf. Healey held the post until the defeat of the Labour government in the 1970 General Election.

Edward Heath and his Conservative government came into conflict with the trade unions over his attempts to impose a prices and incomes policy. His attempts to legislate against unofficial strikes led to industrial disputes. In 1973 a miners' work-to-rule led to regular power cuts and the imposition of a three day week. Heath called a general election in 1974 on the issue of "who rules". He failed to get a majority and Harold Wilson and the Labour Party were returned to power.

Harold Wilson appointed Healey as Chancellor of the Exchequer. At the 1973 Labour Party Conference he argued: " The main reason for this enormous foreign deficit is that he gave away four thousand million pounds in the last three years in tax reliefs, mainly to the rich, without cutting expenditure to scale and without making any attempt to be sure that British industry had the capacity to meet the consequent increase in demand, so we have had a steady increase in imports of manufactured goods, a yawning trade gap, and continual runs on sterling. But before you cheer too loudly, let me warn you that a lot of you will pay extra taxes, too. That will go for every Member of Parliament in this hall, including me ... There are going to be howls of anguish from the eighty thousand people who are rich enough to pay over seventy-five per cent on the last slice of their income. But how much do we hear from them today of the eighty-five thousand families at the bottom of the earnings scale who have to pay over seventy-five per cent on the last slice of their income - and thirty thousand of them actually lose twenty-five new pence or more, when their wages go up a pound?"

Healey was unable to solve Britain's economic problems and in 1976 Healey was forced to obtain a $3.9 billion loan from the International Monetary Fund. When Harold Wilson resigned that year , Healey stood for the leadership but was defeated by James Callaghan. The following year Healey controversially began imposing tight monetary controls. This included deep cuts in public spending on education and health. Critics claimed that this laid the foundations of what became known as monetarism. In 1978 these public spending cuts led to a wave of strikes (winter of discontent) and the Labour Party was easily defeated in the 1979 General Election.

In 1980 Healey once again contested the leadership of the Labour Party. The left campaigned against his nomination. Ian Mikardo argued in his autobiography Back Bencher (1988): "When the leadership election loomed in 1980 my friends in the Tribune Group and many other people in the Party and the trade unions wanted to stop Healey because he was way out to the Right and was likely to go even further than Wilson and Callaghan in leading the Party away from its socialist principles. But even though I shared that view I had an even stronger motivation for frustrating his leadership bid. I had seen at first hand his emery-paper abrasive manner, his crude strong-arm all-in-wrestling ways of dealing with dissent, his undisguised contempt for many of his colleagues, his actual enjoyment of confrontation, his penchant for pouring petrol on the flames of controversy, and I was thoroughly convinced that if he became Leader of the Party it wouldn't be long before these aggressive characteristics of the would split the Party from top to bottom; and that was a prospect which scared me."

Healey was unexpectedly defeated by Michael Foot and had to be satisfied with the post of deputy leader. Healey resigned from the Shadow Cabinet in 1987. His autobiography, The Time of My Life, was published in 1989.

Denis Healey died on 3rd October, 2015.

Primary Sources

(1) Denis Healey, The Time of My Life (1989)

For the young in those days, politics was a world of simple choices. The enemy was Hitler with his concentration camps. The objective was to prevent a war by standing up to Hitler. Only the Communist Party seemed unambiguously against Hitler. The Chamberlain Government was for appeasement. Labour seemed torn between pacifism and a halfhearted support for collective security, and the Liberals did not count. Everything began to change, of course, with the Stalin-Hitler Pact and the Soviet attack on Finland; but it was at first too easy to rationalise these reversals of Russian policy simply as a reaction to the failure of Britain and France to build a common front against Hitler.

(2) On the outbreak of the Second World War Denis Healey joined the British Army. He wrote about it in his autobiography, The Time of My Life (1989)

Unfashionable though it is to admit it, I enjoyed my five years in the wartime army. It was a life very different from anything I had known, or expected. Long periods of boredom were broken by short bursts of excitement. For the first time I had to learn to do nothing but wait - for me the most difficult lesson of all. To my great relief, I found I did not get frightened in action - not that I enjoyed being shelled or dive-bombed any more than the next man; but fear never paralysed me or even pushed me off my stroke. On the other hand I was never called on to show the sort of active courage which wins men the VC. A dumb, animal endurance is the sort of courage most men need in war. I was constantly amazed by the ability of the average soldier, and civilian, to exhibit this under stress.

(3) Denis Healey, letter to Ivor Thomas, Labour Party MP (February, 1945)

A man pushed blindfold into a courtroom with cotton wool in his ears, obliged to plead for his life without knowing where the jury was sitting or even whether it was in the room at all, would nicely represent my position at this moment... I am only one of the hundreds of young men, now in the forces, who long for the opportunity to realise their political ideals by actively fighting an election for the Labour Party. These men in their turn represent millions of soldiers, sailors and airmen who want socialism and who have been fighting magnificently to save a world in which socialism is possible. Many of them have come to realise that socialism is a matter of life and death for them. But too many others feel that politics is just another civilian racket in which they are always the suckers . .. We have now almost won the war, at the highest price ever paid for victory. If you could see the shattered misery that once was Italy, the bleeding countryside and the wrecked villages, if you could see Cassino, with a bomb-created river washing green slime through a shapeless rubble that a year ago was homes, you would realise more than ever that the defeat of Hitler and Mussolini is not enough, by itself to justify the destruction, not just of twenty years of fascism, but too often of twenty centuries of Europe. Only a more glorious future can make up for this annihilation of the past.

(4) Denis Healey, speech at the Labour Party Conference (21st May, 1945)

The upper classes in every country are selfish, depraved, dissolute and decadent. The struggle for socialism in Europe ... has been hard, cruel, merciless and bloody. The penalty for participation in the liberation movement has been death for oneself, if caught, and, if not caught oneself, the burning of one's home and the death by torture of one's family ... Remember that one of the prices paid for our survival during the last five years has been the death by bombardment of countless thousands of innocent European men and women.

(5) Harold Wilson, Memoirs: 1916-1964 (1986)

I made Denis Healey Minister of Defence. He is a strange person. When he was at Oxford he was a communist. Then friends took him in hand, sent him to the Rand Corporation of America, where he was brainwashed and came back very right wing. But his method of thinking was still what it had been: in other words, the absolute certainty that he was right and everybody else was wrong, and not merely wrong through not knowing the proper answers, but wrong through malice. I had very little trouble with him on his own subject, but he has a very good quick brain and can be very rough. He probably intervened in Cabinet with absolute certainty about other departments more than any minister I have ever known, but he was a strong colleague and much respected.

(6) Denis Healey, speech at the Labour Party Conference (1973)

The main reason for this enormous foreign deficit is that he gave away four thousand million pounds in the last three years in tax reliefs, mainly to the rich, without cutting expenditure to scale and without making any attempt to be sure that British industry had the capacity to meet the consequent increase in demand, so we have had a steady increase in imports of manufactured goods, a yawning trade gap, and continual runs on sterling.

But before you cheer too loudly, let me warn you that a lot of you will pay extra taxes, too. That will go for every Member of Parliament in this hall, including me ... There are going to be howls of anguish from the eighty thousand people who are rich enough to pay over seventy-five per cent on the last slice of their income. But how much do we hear from them today of the eighty-five thousand families at the bottom of the earnings scale who have to pay over seventy-five per cent on the last slice of their income - and thirty thousand of them actually lose twenty-five new pence or more, when their wages go up a pound?

(7) Edward Heath, The Course of My Life (1988)

Between March and October 1974 the Labour government acted as we had expected. Denis Healey, the new Chancellor, reversed our income tax cuts in the first of two 1974 budgets. The basic rate was increased from 30 to 33 per cent, and Value Added Tax was extended to sweets, soft drinks and ice cream. Corporation tax and stamp duty were significantly increased. Overall, the tax burden was increased by over .£2,000 million per year in this budget, about £12,000 million in today's values. Significant price increases were announced for the products of nationalised industries, including coal and steel. Postal charges also rose considerably.

(8) Denis Healey, wrote about his period as Chancellor of the Exchequer in his autobiography The Time of My Life (1989)

However, once the pay policy was in place in 1975, my overriding concern was to restore a healthy financial balance both at home and abroad. It had become customary among Keynesians - who had usually read no more of Keynes than most Marxists had read of Marx - to claim that there was no need to worry about a fiscal deficit when the economy was working below capacity, nor about a deficit on the current balance of payments when foreign capital was pouring into Britain. In 1975 unemployment was rising, and the Arab countries were parking their surplus oil revenues in British banks for the time being. So in theory there was no harm in running substantial deficits both at home and abroad.

However, the trouble with deficits is that they have to be financed by borrowing; and in the negotiation for a loan it is the lender who decides the interest rate and sets the conditions. It was obvious that before long the Arab countries would start diversifying their surpluses more widely round the world; and in any case their surpluses would shrink as their own development plans got under way. If we were not to become dependent on borrowing from other foreigners and from the IMF, we must try to eliminate our current account deficit within a few years. And we would be unable to reduce our external deficit if our internal fiscal deficit was still growing.

So I decided to reduce the PSBR by raising taxes and cutting public spending, so that firms would be compelled to export what they could not sell at home. It was a Herculean task. The enormous interest payments Britain had incurred by borrowing to finance its twin deficits since the Barber boom started in 1971, meant that we had to run very fast even to stand still. Yet we managed to complete the most important part of our task in just three years. In fact the latest statistics show that we had eliminated our balance of payments deficit in 1977. By the middle of 1978 our GDP was growing over three per cent a year, as against a fall of one per cent in 1975/6. Unemployment, which rose very fast in my first three years, had been falling for nine months; and inflation was below eight per cent. It was one of the few periods in postwar British history in which unemployment and inflation were both falling at the same time.

All this was achieved at a time when we were getting little benefit from North Sea oil. The capital investment required made it a net drain on our balance of payments in my early years. Even in 1978, North Sea oil was making good only half the impact of the OPEC price increase on our balance of payments, and was not yet producing any revenue for the Government.Politically, by far the most difficult part of my ordeal was the continual reduction of public spending; almost all of the spending cuts ran against the Labour Party's principles, and many also ran against our campaign promises. Here again, my task was complicated by the Treasury's inability either to know exactly what was happening, or to control it. In November 1975 Wynne Godley, who had himself served in the Treasury as an economist, showed that public spending in 1974/5 was some £5 billion higher in real terms than had been planned by Barber in 1971. This was one of the reasons why I decided to fix cash limits on spending as well as pay, since departments tended to use inflation as a cover for increasing their spending in real terms. Cash limits worked all too well in holding spending down. Departments were so frightened of exceeding their limits that they tended to underspend, sometimes dramatically so. In 1976/7 public spending was £2.2 billion less than planned.

(9) Ian Mikardo, Back Bencher (1988)

In the meanwhile the Callaghan Government dragged to its miserable close, and after its suicide in 1979 it was clear that Jim would resign from his office as Leader within the next year or eighteen months. When the time actually came, in October 1980, the question of who was to succeed him was complicated by the fact that, while the constitution provided that the Leader and his Deputy were elected by the Parliamentary Party alone, there was a proposal before the Party to amend the constitution so as to widen the franchise by setting up an electoral college of the PLP plus the Constituency Parties plus the trade unions, and that amendment was due to be put to a special Party Conference to be held a few months later.

The Left in the PLP were keen to postpone the election of a new Leader till then by appointing the current Deputy Leader, Michael Foot, as a caretaker for the short period up to the constitutional conference. The Right, by contrast, wanted the election held at once by the PLP alone, because they could be expected to elect the Right's favoured candidate, Denis Healey. Some of Callaghan's ex-Ministers issued statements in support of this proposal: they included three or more of those who later became the Gang of Four and a number of their friends who also defected to the SDP. They got their way, and the election went ahead with the PLP as the electoral constituency.

To go back to the beginning, Jim announced his resignation to the Shadow Cabinet at their regular Wednesday afternoon meeting on 15 October 1980. As soon as he'd finished his resignation statement Michael Foot paid a long and warm tribute to him. (Michael had characteristically given continuously faithful and selfless loyalty to Jim throughout the two turbulent years of Jim's premiership, and Jim returned evil for good by undermining Michael's leadership during the 1983 election campaign.) After the Shadow Cabinet meeting three of the left wing members of the Shadow Cabinet and one semi-left winger - Albert Booth, Stan Orme, John Silkin and Peter Shore - went off to Silkin's room to discuss what to do next. The remaining two of their little group, Michael himself and Tony Benn, were tied up and weren't able to attend. The four who were there agreed that their objective must be to try to prevent the election of Denis Healey: Peter Shore said that he thought he had a good chance of beating Denis; John Silkin went much further and claimed confidently that he would certainly beat Healey and anyone else who might stand.

The stop-Healey urge was one which I shared in full measure, but more than once I asked myself sharply why I was so keen to keep out of the Party's top position a man for whom I had, as I still have, great admiration and a very high regard. Denis is an outstanding talent, equalled by very few people I've met in the whole of my long innings. When he speaks on international affairs, he speaks with the authority that derives from an unmatched knowledge of what's going on in almost every country in the world, and his analysis of all those movements of events is almost always penetrating and enlightening. He is a cultured man of parts, of many interests outside politics (those politicians whose lives contain nothing but politics are always second-class politicians). He's a bubbly, witty man who can be a charming and entertaining companion.

Now that he has mellowed, as we all do (not least I) after we get our senior-citizens' bus-passes, he exudes the milk of human kindness; but in the 1960s and 1970s he was a political bully wielding the language of sarcasm and contempt like a caveman's cudgel. He didn't argue with those members of the Party who didn't agree with him, he just wrote them off. He once described a Cabinet colleague who dared to differ from him as having a "tiny Chinese mind". More than once, in my own arguments with him, he didn't reply to what I'd said but instead quoted me as saying something nonsensical which I had never said. He knew all the tricks, and used them ruthlessly.

When the leadership election loomed in 1980 my friends in the Tribune Group and many other people in the Party and the trade unions wanted to stop Healey because he was way out to the Right and was likely to go even further than Wilson and Callaghan in leading the Party away from its socialist principles. But even though I shared that view I had an even stronger motivation for frustrating his leadership bid. I had seen at first hand his emery-paper abrasive manner, his crude strong-arm all-in-wrestling ways of dealing with dissent, his undisguised contempt for many of his colleagues, his actual enjoyment of confrontation, his penchant for pouring petrol on the flames of controversy, and I was thoroughly convinced that if he became Leader of the Party it wouldn't be long before these aggressive characteristics of the would split the Party from top to bottom; and that was a prospect which scared me.

(10) The Guardian (22nd March, 2009)

A former Conservative leader has claimed that Margaret Thatcher would not have survived as Prime Minister, had former Labour chancellor Denis Healey not paved way for 1976 bailout. Iain Duncan-Smith has said that Healey, who negotiated with the International Monetary Fund in 1976, deserves credit for the economic achievements of the Thatcher government. You have to remember it was Denis Healey who did most of the serious hard work, the heavy lifting, before Thatcher came in. Had she come in without Healey’’s work in the IMF, I don”t think she”d have lasted two years. She would have been out in 1983, The Scotsman quoted Duncan-Smith, as saying. During Prime Minister Jim Callaghans regime, he was forced to saw him go ”cap in hand” to the IMF for a loan after sterling tumbled to a record low against the US dollar, Duncan-Smith claimed. Britain’’s position by 1978-9 was appalling we were just disappearing as a nation. It simply was not possible to go on any longer, he said. Duncan-Smith, who stood down from the Tory leadership after losing a vote of confidence in 2003, claims that some of today’’s social ills were a legacy of the Thatcher era. While I”m not going to point the finger and say the changes made in the Eighties were wrong, we didn”t have any real sense of where this might go. Big social reforms should have taken place then, and they never did, he said. Duncan-Smith also criticized Thatchers council house sell-off policy, which was considered as one of her greatest achievements. Nobody really thought about what happens if you allow only the most broken families to exist on housing estates. You create a sort of ghetto in which the children who grow up there repeat what they see around them, he said.