Richard the Lionheart

Richard the Lionheart, the third son of Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine, was born at Beaumont Palace on 8th September 1157. He was the younger brother of Eleanor's first children, William IX of Poitiers (17th August 1153), Henry the Young (28th February 1155) and Matilda (6th January, 1156).

Later his mother gave birth to Geoffrey of Brittany (23rd September 1158), Eleanor (13th October 1162), Joan (October 1165) and John (24th December 1166). Henry II also had extra-marital affairs and had several illegitimate children, including Geoffrey, the Archbishop of York. (1)

Richard was given into the care of a nurse, Hodierna of St Albans, whose own son, Alexander Nequam, had been born the same night. Hodierna took care of Richard for the next few years. His foster-brother "grew up to be one of the greatest scientists of the age, the author of a treatise on natural history and the first European to study magnetism." (2)

His biographer, John Gillingham has pointed out that nothing is known of his education, but it is clear he obtained a conventionally good one. "He was able to enjoy a Latin joke at the expense of a less learned archbishop of Canterbury. His interest in words and music was such that he became not just a patron of troubadours, but also a songwriter with a poetic voice very much his own." (3)

Ralph de Diceto claimed that Richard was special to Eleanor from birth. (4) They definitely spent a lot of time together as he spent most of his youth at his mother's court at Poitiers, that was famous for its troubadours and their songs of chivalry and courtly love. He was also educated in the art of war and took an active part in tournaments. (5)

Richard, Duke of Aquitaine

Negotiations took place between King Henry II of England and King Louis VII of France. In 1169 it was decided at a meeting at Montmirail that Henry the Young would inherit Normandy, Anjou and England after his marriage to the 12-year-old Margaret. It was also agreed that Henry's 12-year-old son, Richard, would marry Alais, another daughter of Louis VII. (6)

The following year Eleanor arranged for Richard to be granted the title of Duke of Aquitaine. Eleanor, dealt with the problems of imposing taxes on individuals and commodities such as wheat, salt and wine. Over the next few years Richard "got his first taste of the exercise of authority in his mother's company, and in her ancestral territories". (7)

On 27th August 1172, Richard's brother, Henry the Young, aged seventeen, married Margaret of France. It would hoped that if Margaret gave birth to a son, who would have a claim to both family empires. However, they remained childless. (8) Henry developed an expensive life-style without the means to pay for it and was heavily in debt. His father had promised him that he would one succeed him as king of England, and inherit land in Normandy and Anjou. He also endowed him with titles, but "as he approached manhood his access to landed revenue and power - the essence of kingship - was strictly limited". (9)

Revolt against Henry II

Eleanor of Aquitaine suggested that Henry the Young should be given England, Anjou or Normandy to rule. Henry refused and Eleanor began to develop plans to overthrow of her husband. On 5th March 1173, Henry left Chinon Castle and rode for Paris and went to stay with King Louis VII. Soon afterwards, Louis announced that he acknowledged that Henry was the new king of England. Henry II was furious and declared war on France. He was greatly dismayed when he heard that Eleanor and two more of his sons, Richard and Geoffrey, had joined the rebellion. (10)

William of Newburgh reported that "the younger Henry, devising evil against his father from every side by the advice of the French King, went secretly into Aquitaine where his two youthful brothers, Richard and Geoffrey, were living with their mother, and with her connivance, so it is said, he incited them to join him". (11) One historian has pointed out that the brothers "were typical sprigs of the Angevin stock... they wanted power as well as titles". (12)

Andrea Hopkins has argued that Eleanor identified more with the interests of her sons rather than those of her husband. (13) Eleanor of Aquitaine has been accused of being the ring-leader of the revolt against Henry: "It is clear that her sympathies lay wholeheartedly with her sons and that, like a lioness fighting to protect her cubs, she was prepared to resort to drastic measures to ensure that they received their just deserts... Henry and his brothers wanted autonomous power in the hands assigned to them, even if it meant the overthrow of their father; Eleanor wanted justice for her sons and, consequently, more power and influence for herself. This, she must have known, could only be achieved through the removal of her husband from the political scene." (14)

In a letter sent to Eleanor by Rotrou, Archbishop of Rouen, under the instructions of Henry II, he made it clear that he considered that his wife was behind the revolt as she had "made the fruits of your union with our Lord King rise up against their father". He added: "before events carry us to a dreadful conclusion, return with your sons to the husband whom you must obey and with whom it is your duty to live... Bid your sons, we beg you, to be obedient and devoted to their father." (15)

Eleanor's powerful lords from Aquitaine joined the rebellion. Henry the Young also did a deal with William the Lion, the King of Scotland, who promised him Northumbria if he helped defeat his father. However, before the fighting began, Eleanor was captured by the agents of Henry. According to Gervase of Canterbury, Eleanor, left Poitiers for Chartres, on a horse, dressed as a man. She was recognized and arrested and taken to Henry who was based in Rouen. (16)

In July 1173 Henry defeated his sons at Verneuil Castle. His soldiers also had success against the Scots in Northumbria. His loyal commander, Richard de Lucy, defeated hired bands of Flemish mercenaries at Fornham, near Bury St Edmunds. (17) By the end of September 1174 it was all over. After their surrender, Henry, Richard and Geoffrey all had their allowances increased. Henry was formally assigned two castles in Normandy, to be chosen by his father, and 15,000 Angevin pounds for his upkeep. (18) However, all three sons had to promise never to "demand anything further from the Lord King, their father, beyond the agreed settlement... and withdrew neither themselves nor their service from him." (19)

However, he was unwilling to forgive Eleanor and she spent the next fourteen years in captivity. The records suggest that she was permitted two chamberlains and a maid named Amaria. Lisa Hilton, the author of Queens Consort: England's Medieval Queens (2008) claims that although "Eleanor's living conditions were reasonable, they were not commensurate with her status, as her clothes were no finer than a servant girl's and apparently she and Amaria had to share the same bed." (20)

Death of Henry the Young

On 19th June, 1177, Henry the Young's wife, Margaret, finally gave birth to her first child, William. The joy at the birth of a direct heir to the Angevin empire was short-lived, for the infant died three days later. Matthew Strickland, the author of Henry the Young King (2016) has pointed out: "Whereas his father's extra-marital affairs were as numerous as they were notorious, young Henry is not known to have had any mistresses, or to fathered any illegitimate children... this was unusual among men of his rank and power." (21)

In 1182 Henry the Young renewed his demands for more power, and once again fled to the French court in defiance of his father. Henry II responded by increasing his allowance by an extra 110 Angevin pounds a day for himself and his wife. However, this did not stop him supporting the rebellious barons of Aquitaine against his brother, Richard the Lionheart, who was trying to bring this area under control. The king sent his soldiers to help Richard against his rebellious son. "Returning from a raid on Angoulême, however, he was refused entry to Limoges by its exasperated citizens, and set off on a haphazard expedition around southern Aquitaine, despoiling the monastery of Grandmont and the shrines of Rocamadour." (22) Peter of Blois accused Henry the Young of being "a leader of freebooters who consorted with outlaws and excommunicates". (23)

Henry the Young fell seriously ill with dysentery. A message was sent to Henry II informing him that his son was dying. The king's advisors suspected a trap and warmed against him visiting his son. He therefore sent his physician, some money and as a token of his forgiveness, a sapphire ring that had belonged to Henry I. He also said that he hoped that after his son recovered, they would be reconciled. When he received the ring he replied asking his father to show mercy to his mother, Queen Eleanor. (24)

Henry the Young realised he was dying and "overcome with remorse for his sins, asked to be garbed in a hair shirt and a crusader's cloak and laid on a bed of ashes on the floor, with a noose round his neck and bare stones at his head and feet, as befitted a penitent." Henry the Young died on 11th June, 1183. (25) The following year Henry II held a meeting in London with Richard and they agreed to bring an end to their conflict. Despite threats that he would be disinherited, Richard continued to have a difficult relationship with his father. (26)

Richard the Lionheart

In the autumn of 1183, King Henry II told Richard that he should give up Aquitaine to his youngest brother, John, who had always remained loyal to his father. In return, he would become heir to England, Normandy and Anjou. Richard refused as he believed as the eldest son left alive, he should inherit all his father's empire when he died. He also rejected the suggestion that another brother, Geoffrey, should be given Brittany to rule. (27) Henry now came up with another plan. He told Richard he would release his mother, Eleanor of Aquitaine, from prison, if he agreed to surrender his rights to Aquitaine. Richard, who was devoted to his mother, agreed to this suggestion. (28)

One of his main rivals, his brother Geoffrey, died aged twenty-seven on 19th August, 1186. Roger of Howden said he succumbed to fever. (29) However, Ralph de Diceto, claims he took part in a tournament and fell off his horse and was trampled to death. (30) A son and heir, Arthur of Brittany, was born six months after his death. (31)

In January 1189, King Henry II became ill. From his sickbed he sent messages begging Richard the Lionheart to return to his side. However, he continued to fight alongside Philip II and he considered nominating his youngest son, John, as his heir. On 12th June Richard attacked Henry at his base in Le Mans. Henry was forced to flee and was taken to Chinon Castle. (32)

By the end of the month Maine was overrun and Tours had fallen. On 3rd July, Henry left his sickbed to meet Philip II at Ballan-Miré. He accepted his long list of demands including the confirmation of Richard as his heir in all lands on both sides of the Channel. Henry was so ill that the fifty-six year old king had to be held upright on his horse by his attendants. After signing the treaty he was too sick to ride and was carried home in a litter. On his return, Henry asked for a list to be drawn up of his former supporters who had joined Richard's rebellion. According to Gerald of Wales, the name at the top of the list was his favourite son John. (33)

Richard the Lionheart (2009)

King Henry II died on 6th July 1189. Richard the Lionheart now became king of England. One of his first acts as king was to send William Marshal to England with orders to release his mother from prison. Richard also restored to her control the lands and revenues that she had enjoyed before the revolt of 1173. (34) Eleanor responded by touring England encouraging the barons to support her son and announced a general amnesty of prisoners. (35) Roger of Howden claims she went from "city to city and castle to castle", holding "queenly courts", releasing prisoners and exacting oaths from all freemen to "be loyal to her son as their as yet uncrowned king". (36)

For many years Eleanor of Aquitaine had been trying to persuade Richard to get married. She had initially selected Alais, the daughter of King Louis VII. However, he rejected the idea: "Although he had always been close to her (Eleanor) and even though he had been reared in a feminine court, where were respected, he did not like the female sex. Not only was he averse to marrying Alais because she had been his father's mistress, he objected to marrying any woman... For good or ill, she had molded the Coeur de Lion, whose name would be synonymous with valor eight centuries later. The only flaw in her planning was that her son was a homosexual." (37)

On 3rd September 1189, Richard was crowned king at Westminster Abbey on 3rd September 1189. "Crowds turned out to glimpse a man of whom they would have seen almost nothing in the thirty-two years of his life. They were greeted by a tall, elegant man, with reddish blond hair and long limbs, proceeding in splendor towards the first coronation in a generation." (38)

Richard stayed in England only long enough to make the necessary financial arrangements for his involvement in the Third Crusade. This involved selling some of his recently acquired land. He even joked that he would sell London if he could find a buyer. Roger of Howden claimed that "he (Richard) put up for sale all he had: offices, lordships, earldoms, sheriffdoms, castles, towns, lands, everything." (39)

According to Charles Scott Moncrieff: "Richard tended to regard England mainly as a piece of property from which, by taxes or other means, he could raise money for the Crusades. He got it chiefly in large lump sums from the wealthier people." Richard sold the Archbishop of York for £2,000. He put Ranulf de Glanville, the former Chief Justiciar of England and one of the richest men in the country, in prison and only released him when his family paid Richard £15,000. (40)

John met with Richard before he left England. King Richard gave his brother the title Count of Mortain and confirmed him Lord of Ireland. He also "bestowed on him other fiefs and castles, and assigned to him the entire royal revenues of six English counties, Cornwall, Devon, Somerset, Dorset, Derby and Nottingham". However, John was disappointed that the king had not given him any real power in administering England while he was away. (41)

Dan Jones, the author of The Plantagents (2013) has argued that Richard decided to change the way he ruled the country: "He (Richard) looked at the Plantagent empire he had inherited and saw revenue streams where his father had not. Henry had generally balanced the profits that could be derived from the sale of office and royal favour against the need to offer kingship based on stable government by competent royal servants. Richard was never so keenly bureaucratic." It is estimated that he spent around £14,000 on food and equipment for the campaign. This included "14,000 cured pig carcasses, 60,000 horseshoes, huge numbers of cheeses and beans, thousands upon thousands of arrows." (42)

On 15th September 1189, Richard the Lionheart arranged for Hubert Walter, to be elected bishop of Salisbury. In return, Walter made it clear that he was willing to serve with Richard in the Holy Land. Richard the Lionheart left his mother Eleanor in charge of the government. One of her first decisions was refusing permission for the papal legate, John of Agnani, to visit London. On 12th December, 1189, Richard sailed from Dover to Calais on his way to the Holy Land. He appointed Hugh de Puiset as justiciar and William Longchamp as chancellor. Although she was not formerly designated regent, "it is clear that both de Puiset and Longchamp deferred to her authority". (43)

Bishop Walter and Baldwin of Forde, Archbishop of Canterbury, arrived in Tyre on 16th September 1190. (44) In early October they joined the crusader army besieging Acre. Conditions in the crusader camp were terrible, and Baldwin died 19th November 1190. Bishop Walter now became the leader of the English contingent at Acre, and quickly began to reorganize the camp. He was also willing to lead military expeditions against Saladin, the Muslim leader. (45)

According to his biographer, Robert Stacey: "Bishop Walter an executor of Baldwin's will, he used the archbishop's possessions to pay wages to the sentries and buy food for the starving common soldiers. He led sorties against Saladin's camp, and also ministered to the religious needs of the army. Morale rose; and when King Richard at last arrived at Acre in June 1191, having spent the winter in Messina, he found the army in far better shape than it had been six months before." (46)

N.C. Wyeth, Richard the Lionheart (1921)

On the way to the Holy Land, Richard married Berengaria of Navarre, the daughter of King Sancho VI of Navarre. William of Newburgh suggests that the marriage was arranged by Eleanor as she wanted him to have an "incontestable heir". (47) Walter of Guisborough claims that Richard had married Berengaria "as a salubrious remedy against the great perils of fornication". (48) The wedding was held in Limassol on 12th May 1191 at the Chapel of St. George. Richard took his new wife on crusade with him briefly but she returned home before Richard became involved in any fighting. The marriage did not produce any children. (49)

Richard was considered to be the best military commander in the Christian world. On 8th June, 1191, Richard joined the army that had been besieging Acre for nearly two years. Saladin, the Muslim leader, attempted to take the besiegers' heavily fortified camp by storm was beaten back on 4th July. The exhausted defenders capitulated. Terms were agreed on 12th July: the garrison to be ransomed in return for 200,000 dinars and the release of 1,500 of Saladin's prisoners. (50)

In January 1192, Richard the Lionheart had reached Bayt Nuba, 12 miles from Jerusalem. Richard realised that if he managed to take the city, "they did not have the numbers to occupy and defend it especially since many of the most devout crusaders, having fulfilled their pilgrim vows, would at once go home". He decided to take Acre instead. Soon after this military success he heard that his brother, John, had joined Philip II of France, in an attempt to overthrow his government in England. (51)

Richard the Lionheart's seal (c. 1190)

Richard the Lionheart now reopened negotiations with Saladin so he could return to England. By now both sides were weary, and Richard himself fell seriously ill. A three-year truce was agreed on 2nd September. Richard had to hand back Ascalon; Saladin granted Christian pilgrims free access to Jerusalem. Many crusaders took advantage of this facility. "He had failed to take Jerusalem, but the entire coast from Tyre to Jaffa was now in Christian hands; and so was Cyprus. Considered as an administrative, political, and military exercise, his crusade had been an astonishing success." (52)

King Richard never met Saladin. After signing the peace agreement he sent a message to the sultan that he would return later to conqueror the Holy Land. Saladin wrote back accepting the challenge saying he could think of no king to whom he would sooner lose his empire. But the sultan had less than a year to live, and the two men were never to stage their rematch. (53)

Winston Churchill claims that Richard the Lionheart, despite his many faults, was one of England's most important heroes. "His memory has always stirred English hearts, and seems to present throughout the centuries the pattern of the fighting man. Although a man of blood and violence, Richard was too impetuous to be either treacherous or habitually cruel. He was as ready to forgive as he was hasty to offend; he was open-handed and munificent to profusion; in war circumspect in design and skilful in execution; in politics a child, lacking in subtlety and experience. His political alliances were formed upon his likes and dislikes; his political schemes had neither unity nor clearness of purpose." (54)

On his way home in December 1192, Richard was captured by Duke Leopold of Austria. Bishop Hubert Walter immediately began negotiating terms for Richard's release. In March 1193 Bishop Walter left for England carrying letters from the captive king concerning his ransom. Among these letters was the king's command to Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine to have Hubert Walter elected archbishop of Canterbury. (55)

When news of Richard's capture reached Philip II of France he suggested to his brother John that they should take advantage of the situation. In January 1193 at Paris the two men signed a peace treaty which involved marrying Philip's sister, Alys. (56) In return, Philip promised to help him gain control of England. This included the attempt to persuade Duke Leopold to sell Richard to Philip for £100,000. (57)

Archbishop Walter played an important role in raising the £100,000 ransom money. "New taxes were invented and old ones revived; churches gave gold and silver vessels; a special tax of one-fourth was levied on all incomes." (58) The English people were subject to a 25 per cent on tax on income and movables. Monasteries and churches around England also had to contribute. (59) Ralph de Diceto commented that "Archbishops, bishops, abbots, priors, earls and barons contributed a quarter of their annual income; the Cistercian monks and Premonstratensian canons their whole year's wool crop, and clerics living on tithes one-tenth of their income." (60)

In March 1193 Richard the Lionheart was put on trial. William the Breton wrote that he "spoke so eloquently and regally, in so lionhearted a manner, it was as though he were seated on an ancestral throne at Lincoln or Caen". He claimed that some of the assembled magnates and courtiers were so impressed with the speech that many were "moved many to tears". (61)

Over the next six months his mother, Eleanor of Aquitaine, helped to raise the £100,000 ransom money. "New taxes were invented and old ones revived; churches gave gold and silver vessels; a special tax of one-fourth was levied on all incomes." (62) Eleanor, who told the Pope Celestine III in a letter that she was "worn to a skeleton" made an extended visit to Germany. "This was far more than a visit of ceremony, for it had been preceded by a stream of letters concerning the conduct of government within the kingdom and the raising of the king's ransom". (63)

John Lackland decided to make a bid for power while his brother was imprisoned. Based in Windsor Castle he urged the magnates to join him in his rebellion. After summoning a council to condemn John and his followers, in February 1194 Walter himself led the successful siege of Marlborough Castle and a few weeks later he personally accepted the peaceful surrender of Lancaster Castle. (64)

Archbishop Hubert Walter urged Queen Eleanor and the regency council to adopt a conciliatory policy towards John. He was not optimistic about Richard's chances of being released and if John became king he might exact vengeance on those who had opposed or offended him. He also pointed out that John's co-operation in raising ransom money from his tenants might be needed. Eleanor and the magnates took Hubert's advice and negotiated a truce with John. He agreed to surrender his castles to his mother and if they were unable to get Richard back, he would become king. (65)

Richard was not released until 4th February, 1194. According to the chronicler Roger of Howden, King Philip II of France wrote urgently to John to tell him the news. "Look to yourself, the devil is loose." (66) Richard landed in Sandwich on 20th March, having been away for nearly four years. Ralph de Diceto wrote that three days later "to the great acclaim of both clergy and people, he was received in procession through the decorated city of London into the church of St Paul's". (67)

Richard was upset with John and after he arrived back in England he seized his brother's most important castle at Nottingham and summonded John to appear before his Court within forty days in order to undergo judgment as a rebel. John refused and instead fled to France. (68)

Richard devoted the next five years to successfully recovering the territory he had lost while he was in prison. Having raised an army he travelled to Portsmouth with his mother and they set sail for the continent with one hundred ships on 12th May 1195. (69) Neither of them would ever set foot in England again. (70)

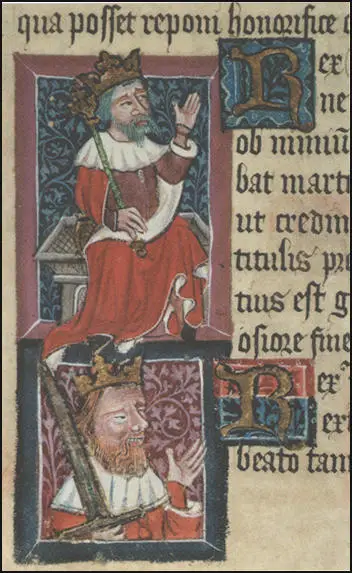

Thomas Walsingham's Golden Book of St Albans (1380)

Richard and Eleanor travelled to Lisieux. They were joined by John who "falling at his feet... sought and obtained his clemency". Richard raised him up and gave him the kiss of peace, saying, "Think no more of it, John. You are but a child, and were left to evil counsellors. Your advisers shall pay for this. Now come and have something to eat". He then commanded that a gift of fresh salmon, be cooked and served to John. During the campaign John fought loyally beside his brother. (71)

In 1197 Richard the Lionheart took back Normandy from King Philip II of France and "laid waste wide swathes of Philip's territories, plundering, burning, looting and killing; not even priests were spared." Many of the Philip's vassals declared for Richard, while others chose to remain neutral. Philip II was forced to accept defeat. (72)

On 25th March 1199, Richard arrived at Châlus-Chabrol, a small castle belonging to Aimar de Limoges. While walking around the castle perimeter without his chainmail, he was struck by a crossbow bolt in the left shoulder near the neck. Mercadier, his loyal lieutenant, attempted to remove the arrow head but "extracted the wood only, while the iron remained in the flesh... but after this butcher had carelessly mangled the King's arm in every part, he at last extracted the arrow." (73)

Within a day or so the wound grew inflamed and then putrid and Richard began to suffer the effects of gangrene and blood-poisoning. Richard knew he was dying and the man who fired the arrow, Bertram de Gurdun, was brought before him. Richard asked him why "you have killed me?" He replied: "You slew my father and my two brothers with your own hand... Therefore take any revenge on me that you may think fit, for I will readily endure the greatest torments that you can devise, so long as you have met with your end, having inflicted evils so many and so great upon the world." Richard was so moved and impressed with Gurdun's speech that he ordered him to be released. (74)

Richard named John as his heir before dying on 6th April 1199. Some sources claim that Mercadier took revenge on Gurdun and "first flayed him alive, then had him hanged". (75) However, Frank McLynn, the author of Lionheart & Lackland: King Richard, King John and the Wars of Conquest (2006) has pointed out that one source argues that Mercadier sent Gurdun to Richard's sister Joan, "who put him to death in some gruesome way." (76)

Primary Sources

(1) John Gillingham, The Lives of the Kings and Queens of England (1975)

Henry II was still only in his thirties and had no intention of allowing his young sons to govern for themselves. Frustrated, Henry, Richard and Geoffrey broke out into rebellion in 1173. In May 1174 Richard took command of his first serious campaign but at the age of sixteen he was still no match for his father and he was soon forced to ask pardon.... Richard was, above all else, a great soldier. His own individual prowess in battle was an inspiration to his men.

(2) Charles Scott Moncrieff, Kings and Queens of England (1966)

Richard tended to regard England mainly as a piece of property from which, by taxes or other means, he could raise money for the Crusades. He got it chiefly in large lump sums from the wealthier people. For instance, he sold the Archbishopric of York for £2,000. He put Ranulf Glanvill in prison, for no reason except that the old man rich - King Henry's strong sense of justice not having descended to his sons - and this fetched a ransom of £15,000.

(3) Roger of Howden, King Henry the Second , and the Acts of King Richard (c. 1200)

Richard put up for sale everything he had - offices, lordships, earldoms, sheriffdoms, castles, towns, lands, the lot.

(4) Dan Jones, The Plantagenets (2013)

Crowds turned out to glimpse a man (Richard the Lionheart) of whom they would have seen almost nothing in the thirty-two years of his life. They were greeted by a tall, elegant man, with reddish blond hair and long limbs, proceeding in splendor towards the first coronation in a generation.

He (Richard) looked at the Plantagenet empire he had inherited and saw revenue streams where his father had not. Henry had generally balanced the profits that could be derived from the sale of office and royal favour against the need to offer kingship based on stable government by competent royal servants. Richard was never so keenly bureaucratic.

(5) Winston Churchill, The Island Race (1964)

His memory has always stirred English hearts, and seems to present throughout the centuries the pattern of the fighting man. Although a man of blood and violence, Richard was too impetuous to be either treacherous or habitually cruel. He was as ready to forgive as he was hasty to offend; he was open-handed and munificent to profusion; in war circumspect in design and skilful in execution; in politics a child, lacking in subtlety and experience. His political alliances were formed upon his likes and dislikes; his political schemes had neither unity nor clearness of purpose.

(6) Marion Meade, Eleanor of Aquitaine (2002)

Although he (Richard the Lionheart) had always been close to her (Eleanor) and even though he had been reared in a feminine court, where were respected, he did not like the female sex. Not only was he averse to marrying Alais because she had been his father's mistress, he objected to marrying any woman... For good or ill, she had molded the Coeur de Lion, whose name would be synonymous with valor eight centuries later. The only flaw in her planning was that her son was a homosexual.

(7) Baha ad-Din ibn Shaddad, was an official in the government of Saladin, the sultan of Egypt and leader of the Muslims (c. 1190)

Richard... was a man of great courage and spirit. He had fought great battles and showed a burning passion for war... To gain his ends he sometimes uses soft words, at other times violent deeds.

(8) Gerald of Wales, Concerning the Instruction of a Prince (c. 1190)

The King (Richard the Lionheart) is like a robber permanently on the prowl, always probing, always searching for the weak spot where there is something to steal.

(9) Roger of Howden, King Henry the Second , and the Acts of King Richard (c. 1200)

Bertram de Gurdun, aimed an arrow from the castle, and struck the king on the arm... After its capture, the king ordered all the people to be hanged... except the man who wounded him... Marchades, who, after attempting to extract the iron head, extracted the wood only, while the iron remained in the flesh; but after this butcher had carelessly mangled the king's arm in every part, he at last extracted the arrow... The king now knew he was going to die... he ordered Bertram de Gurdun, who had wounded him, to come into his presence, and said to him, "What harm have I done to you, that you have killed me?" He replied, "You killed my father and my two brothers with your own hand... take any revenge on me that you may think fit, for I will readily endure the greatest torments you can devise, so long as you have met with your end, after having inflicted evils so many and so great upon the world." On this the king ordered him to be released... Marchades, however, seized him without the king knowing it, and after the king's death, had him hanged.

(10) Stephen Church, King John: England, Magna Carta and the Making of a Tyrant (2015)

The death of King Richard on 6th April 1199 came as a surprise to all. He was just forty-one years old, he had survived countless military engagements, a crusade and a year in captivity, and there had been no intimations of mortality. His death was caused by gangrene, which poisoned his system a few days after he had been hit in the shoulder by a crossbow bolt fired from the battlements of the castle of Chalus-Chabrol in the Limousin. The mortally wounded took eleven days to die, during which he had plenty of time to make provision for his soul and to advise on what should happen to his lands once he was dead.

Student Activities

The Life and Death of Richard the Lionheart (Answer Commentary)

Henry II: An Assessment (Answer Commentary)

Medieval and Modern Historians on King John (Answer Commentary)

Medieval and Modern Historians on King John (Answer Commentary)

King John and the Magna Carta (Answer Commentary)

The Peasants' Revolt (Answer Commentary)

Death of Wat Tyler (Answer Commentary)

Medieval Historians and John Ball (Answer Commentary)

Taxation in the Middle Ages (Answer Commentary)

Christine de Pizan: A Feminist Historian (Answer Commentary)

The Growth of Female Literacy in the Middle Ages (Answer Commentary)

Women and Medieval Work (Answer Commentary)

The Medieval Village Economy (Answer Commentary)

Women and Medieval Farming (Answer Commentary)

Contemporary Accounts of the Black Death (Answer Commentary)

Disease in the 14th Century (Answer Commentary)

King Harold II and Stamford Bridge (Answer Commentary)

The Battle of Hastings (Answer Commentary)

William the Conqueror (Answer Commentary)

The Feudal System (Answer Commentary)

The Domesday Survey (Answer Commentary)

Thomas Becket and Henry II (Answer Commentary)

Why was Thomas Becket Murdered? (Answer Commentary)

Illuminated Manuscripts in the Middle Ages (Answer Commentary)