Public Libraries Act

In the 1840s, William Ewart, Joseph Brotherton, and Edward Edwards, became involved in a campaign to obtain a system of public libraries. Brotherton and Ewart were both Liberal MPs but Edwards was a Chartist who was also involved in the struggle for universal suffrage. Edwards, a former bricklayer, had educated himself by spending his non-working time in Mechanics' Institute libraries, and in 1839 became an assistant in the Department of Printed Books in the British Museum.

When William Ewart introduced his Public Libraries Bill in 1849 he encountered considerable hostility from the Conservatives in the House of Commons. It was argued that the rate paying middle and upper classes would be paying for a service that would be mainly used by the working classes. One argued that the "people have too much knowledge already: it was much easier to manage them twenty years ago; the more education people get the more difficult they are to manage." Ewart was therefore forced to make several changes to his proposed legislation before Parliament agreed to pass the measure.

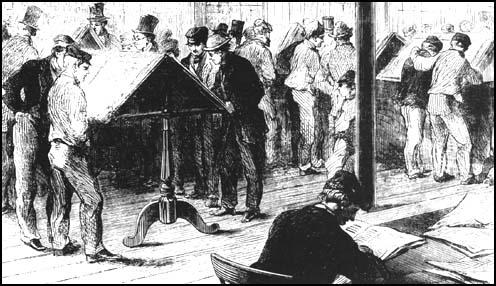

The Public Libraries Act became law in 1850. Whereas William Ewart wanted all boroughs to have the power to finance public libraries, the legislation only applied to those boroughs with populations of over 10,000. The Borough Councils also had to obtain the consent of two thirds of the local ratepayers who voted in a referendum. Other restrictions included that the rate of no more than a halfpenny in the pound could be levied. Furthermore, this money could not be used to purchase books.

William Ewart and Joseph Brotherton continued with their struggle for a more generous and comprehensive approach to public library provision. This led to two amendments to the 1850 Public Libraries Act. In 1853 the act was extended to Scotland and Ireland and in 1855 the rate which could be levied was raised to a penny. Borough Councils were also granted the power to buy reading material for their libraries.

The penny rate still made it impossible for local authorities to provide libraries without the support of wealthy entrepreneurs. These philanthropists usually supported libraries in their own areas. For example, Henry Tate and John Passmore Edwards in London. However, the greatest supporter of public libraries was Andrew Carnegie, who helped to finance over 380 libraries in Britain.

Manchester was one of the first to establish a public library and appointed one of the main campaigners for this reform, Edward Edwards, as its first Chief Librarian. However, Edwards' radical political views resulted in him being dismissed in 1858.

By 1900 there were 295 public libraries in Britain. However, it was not until 1919, when the rate limit was abolished and the formal adoption abandoned, that a truly comprehensive and free library service was possible.