The Combination Acts

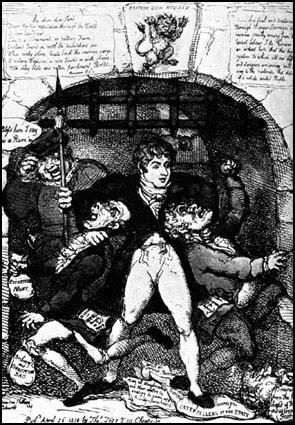

One of the consequences of the industrial revolution was workers began to combine in an attempt to protect their interests. As employers were hostile to these early trade unions, their meetings were often in secret. According to the authors of History of Trade Unionism (1894) pointed out "the midnight meeting of patriots in the corner of the field, the buried box of records, the secret oath, the long terms of imprisonment of the leading officials". (1)

This involved the taking of secret oaths: "The oath was taken at the time of initiation into the union, usually in a private room at a tavern at eight or nine o'clock in the evening. On one side of the apartment was a skeleton, above which a drawn sword and a battle axe were suspended, and in front stood a table upon which lay a bible. The officers of the union wore surplices and addressed each other by their titles of president, vice-president, warden, principal conductor, and inside and outside tiler. The new members were blindfolded for parts of the ceremony, which included the singing of hymns and the recitation of prayers." (2)

In 1799 and 1780 William Pitt, the Prime Minister, decided to take action against political agitation among industrial workers. With the help of William Wilberforce, Combination Laws was passed making it illegal for workers to join together to press their employers for shorter hours or may pay. As a result trade unions were thus effectively made illegal. As A. L. Morton has pointed out: "These laws were the work of Pitt and of his sanctimonious friend Wilberforce whose well known sympathy for the negro slave never prevented him from being the foremost apologist and champion of every act of tyranny in England, from the employment of Oliver the Spy or the illegal detention of poor prisoners in Cold Bath Fields gaol to the Peterloo massacre and the suspension of habeas corpus." (3)

he had been imprisoned for his radical beliefs. (1810)

In the House of Commons, men such as Joseph Hume and Sir Francis Burdett led the fight against this legislation. The Combination Laws remained in force until they were revealled in 1824. This was followed by an outbreak of strikes and as a result the 1825 Combination Act was passed which again imposed limitations on the right to strike. (4)

The campaign against the Combination Acts was led by the trade union leader, Francis Place. "He pulled the Act to pieces; complained of it as an anomaly. It not only repealed the statute law, but forbade the operation of the common law, which had thus introduced a great public evil... The bill had been hurried through the House without discussion. He... predicted the most fatal consequences. Liberty, property, life itself was in danger, and Parliament must speedily interfere." (5)

Trade unionists continued to campaign for a change in the law. In 1867 the government set up a Royal Commission on Trade Unions. George Potter, writing for the Bee-Hive, called for a working man to be included or a "gentleman well known to the working classes as possessing a practical knowledge of the working of Trade Unions, and in whom they might feel confidence." The government rejected the idea of a working man but they did ask Frederic Harrison to serve on the commission. Harrison was a very useful member of the commission, preparing union witnesses by telling them in advance what questions would be asked and rescued the from difficult situations during their cross-examination. (6)

Frederic Harrison, Thomas Hughes and Thomas Anson, 2nd Earl of Lichfield, refused to sign the Majority Report that was hostile to trade unions and instead produced a Minority Report where he argued that trade unions should be given privileged legal status. Harrison suggested several changes to the law: (i) Persons combining should not be liable for indictment for conspiracy unless their actions would be criminal if committed by a single person; (ii) The common law doctrine of restraint of trade in its application to trade associations should be repealed; (iii) That all legislation dealing with specifically with the activities of employers or workmen should be repealed; (iv) That all trade unions should receive full and positive protection for their funds and other property. (7)

The Trade Union Congress campaigned to have the Minority Report accepted by the new Liberal government headed by William Gladstone. This campaign was successful and the 1871 Trade Union Act was based largely on the Minority Report. This act secured the legal status of trade unions. As a result of this legislation no trade union could be regarded as criminal because "in restraint of trade"; trade union funds were protected. Although trade unions were pleased with this act, they were less happy with the Criminal Law Amendment Act passed the same day that made picketing illegal. (8)

Primary Sources

(1) J. F. C. Harrison, The Common People (1984)

The early trade unions were not direct descendants of the gilds which, although designed to protect the interests of all members of a trade, were in practice dominated by the masters. From the second half of the seventeenth century the gilds began to crumble and the journeymen had therefore to look elsewhere for the protection of their interests.

Apprenticeship, wage rates, price lists, tramping, and hours of work had all previously been regulated by gild rules and in some cases by municipal law and act of parliament. In the eighteenth century combinations of journeymen were formed to assume these functions. The early unions were often small and local, and were largely limited to skilled craftsmen: hatters, printers, bookbinders, weavers, woolcombers, shearmen, stockingers, cotton spinners, steam-engine makers, shipwrights, brushmakers, masons, ironfounders, miners, potters, shoemakers, tailors, cutlers, coopers, bricklayers, carpenters-in short, all those known in the nineteenth century and later as the "trades".

Not until the end of the nineteenth century was it considered either practical or desirable to organize labourers. From 1799 to 1824, under the Combination Acts, such combinations of workmen (and also of employers) were illegal. One result of this was to put a premium on secrecy. Even after the repeal of the Combination Acts in 1824 secrecy was continued because of the hostility of employers, who in some cases sought to impose the "document" requiring their men formally to renounce the union.

The oath was taken at the time of initiation into the union, usually in a private room at a tavern at eight or nine o'clock in the evening. On one side of the apartment was a skeleton, above which a drawn sword and a battle axe were suspended, and in front stood a table upon which lay a bible. The officers of the union wore surplices and addressed each other by their titles of president, vice-president, warden, principal conductor, and inside and outside tiler. The new members were blindfolded for parts of the ceremony, which included the singing of hymns and the recitation of prayers.

(2) E. P. Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class (1963)

Even in the darkest war years the democratic impulse can still be felt at work beneath the surface. It contributed an affirmation of rights, a glimpse of a plebeian millennium, which was never extinguished. The Combination Acts (1799-1800) served only to bring illegal Jacobin and trade union strands closer together. Even beneath the fever of the "invasion" years, new ideas and new forms of organization : continue to ferment. There is a radical alteration in the subpolitical political attitudes of the people to which the experiences of tens of thousands of unwilling soldiers contributed. By 1811 we can witness the simultaneous emergence of a new popular Radicalism and of a newly-militant trade unionism. In part, this was the product of new experiences, in part it was the inevitable response to the years of reaction.

(3) A. L. Morton, A People's History of England (1938)

The Industrial Revolution made more formidable combinations possible. When the industrial discontent was crossed with political Jacabinism the ruling class was terrified into more drastic action, and the result was the Combination Laws of 1799 and 1800. These laws were the work of Pitt and of his sanctimonious friend Wilberforce whose well known sympathy for the negro slave never prevented him from being the foremost apologist and champion of every act of tyranny in England, from the employment of Oliver the Spy or the illegal detention of poor prisoners in Cold Bath Fields gaol to the Peterloo massacre and the suspension of habeas corpus.

The Act of 1799, slightly amended in 1800, made all combinations illegal as such, whether conspiracy, restraint of trade or the like could be proved against them or no. In theory, the Act applied to employers as well as to workmen, but though the latter were prosecuted in thousands, there is not a single case of any employer being interfered with. Only too often the magistrates who enforced the law were themselves employers who had been guilty of breaches of it. Prosecutions under the old common law continued to be numerous.

Student Activities

1832 Reform Act and the House of Lords (Answer Commentary)

The Chartists (Answer Commentary)

Women and the Chartist Movement (Answer Commentary)

Benjamin Disraeli and the 1867 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

William Gladstone and the 1884 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Canal Mania (Answer Commentary)

Early Development of the Railways (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)

The Luddites: 1775-1825 (Answer Commentary)

The Plight of the Handloom Weavers (Answer Commentary)

Health Problems in Industrial Towns (Answer Commentary)

Public Health Reform in the 19th century (Answer Commentary)