Hugh Alexander

Hugh Alexander, the eldest of four children of Conel William Long Alexander and Hilda Bennett Alexander, was born in Cork on 19th April 1909. His father was professor of engineering at University College. On his father's death in 1920 the family moved to Birmingham, where he attended King Edward's School. After winning the British boys' championship in 1926, he was soon recognized as one of the future hopes of British chess.

In 1928 Alexander went up to King's College, on a mathematics scholarship. While at Cambridge University he spent a lot of time playing chess: "By 1931 he was playing on top board for Cambridge, winning eleven games in succession. In 1932 he came second in the British championship. He left Cambridge with a first in 1931, but without the star indicating special distinction and so did not get a fellowship. This he rightly attributed to playing too much chess." (1)

Hugh Alexander taught mathematics at Winchester College before becoming Director of Research for the John Lewis Partnership, the leading group of department stores. (2) On 22nd December 1934 he married Enid Constance Crichton, the daughter of a sea captain. Over the next few years Enid gave birth to two sons. He played chess for England and in 1938 won the British championship. (3)

Hugh Alexander - GCCS

On the outbreak of the Second World War a special unit of the Government Code and Cypher School (GCCS) was established at Bletchley Park. This was selected because it was more or less equidistant from Oxford University and Cambridge University and the Foreign Office believed that university staff made the best cryptographers. The house itself was a large Victorian Tudor-Gothic mansion, whose ample grounds sloped down to the railway station. (4)

If you find this article useful, please feel free to share on websites like Reddit. You can follow John Simkin on Twitter, Google+ & Facebook or subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

Hugh Alexander was invited to join the codebreakers in February, 1940. Lodgings had to be found for the cryptographers in the town. Alexander was installed with Stuart Milner-Barry at the Shoulder of Mutton Inn, in Bletchley. Milner-Barry later recalled: "Hugh and I were most comfortably looked after by an amiable landlady, Mrs Bowden. As an innkeeper, she did not seem to be unduly burdened by rationing, and we were able (among other privileges) to invite selected colleagues to supper on Sunday nights, which was a great boon." (5)

Alan Turing

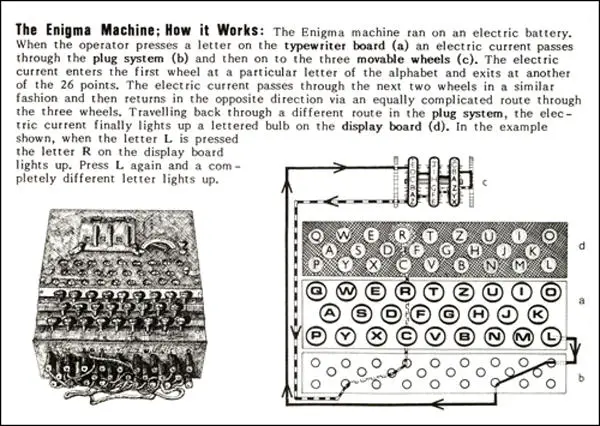

Alexander was based in Hut 8 (Naval Enigma) as deputy head under Alan Turing. According to his biographer, Ralph Erskine: "Documents captured in the spring led to breakthroughs which enabled Hut 8 to solve the main Kriegsmarine cipher, codenamed Dolphin by GCCS, from August onwards. Alexander was outstanding at a Bayesian probability system invented by Turing, called Banburismus, which he considerably improved. Banburismus made the production of operationally useful decodes possible by greatly reducing the number of tests on the ‘bombes’ (high-speed key-finding aids), which were in very short supply." (6)

However, Alexander was keen to point out: "There should be no question in anyone's mind that Turing's work was the biggest factor in Hut 8's success. In the early days, he was the only cryptographer who thought the problem worth tackling and not only was he primarily responsible for the main theoretical work within the Hut (particularly the developing of a satisfactory scoring technique for dealing with Banburismus) but he also shared with Welchman and Keen the chief credit for the invention of the Bombe... the pioneer work always tends to be forgotten when experience and routine later make everything seem easy and many of us in Hut 8 felt that the magnitude of Turing's contribution was never fully realised by the outside world." (7)

Alexander also pointed out that Alan Turing had problems with his superiors over funding: "He (Alan Turing) was always impatient of pompousness or officialdom of any kind indeed it was incomprehensible to him; authority to him was based solely on reason and the only grounds for being in charge was that you had a better grasp of the subject involved than anyone else. He found unreasonableness in others very hard to cope with because he found it very hard to believe that other people weren't all prepared to listen to reason; thus a practical weakness in him in the office was that he wouldn't suffer fools or humbugs as gladly as one sometimes has to." (8)

Commander Edward W. Travis replaced Alastair Denniston as head of GCCS in February, 1941. (9) Later that year, Alexander, Turing, Gordon Welchman and Stuart Milner-Barry wrote a letter to Winston Churchill concerning the funding of GCCS: "Some weeks ago you paid us the honour of a visit, and we believe that you regard our work as important. You will have seen that, thanks largely to the energy and foresight of Commander Travis, we have been well supplied with the 'bombes' for the breaking of the German Enigma codes. We think, however, that you ought to know that this work is being held up, and in some cases is not being done at all, principally because we cannot get sufficient staff to deal with it. Our reason for writing to you direct is that for months we have done everything that we possibly can through the normal channels, and that we despair of any early improvement without your intervention."

The men added: "We have written this letter entirely on our own initiative. We do not know who or what is responsible for our difficulties, and most emphatically we do not want to be taken as criticising Commander Travis who has all along done his utmost to help us in every possible way. But if we are to do our job as well as it could and should be done it is absolutely vital that our wants, small as they are, should be promptly attended to. We have felt that we should be failing in our duty if we did not draw your attention to the facts and to the effects which they are having and must continue to have on our work, unless immediate action is taken." (10)

Churchill told his principal staff officer, General Hastings Ismay: "Make sure they have all they want on extreme priority and report to me that this has been done." (11) By the end of 1942 there were 49 Turing machines. As part of the recruitment drive, the Government Code and Cypher School placed a letter in the Daily Telegraph. They issued an anonymous challenge to its readers, asking if anybody could solve the newspaper's crossword in under 12 minutes. It was felt that crossword experts might also be good codebreakers. The 25 readers who replied were invited to the newspaper office to sit a crossword test. The six people who finished the crossword first were interviewed by military intelligence and recruited as codebreakers at Bletchley Park. (12)

Head of Hut 8

Alan Turing hated administration and by November 1942, Hugh Alexander became head of Hut 8. lan Hodges, the author of Alan Turing: the Enigma (1983) has argued: "Hugh Alexander soon proved the all round organiser and diplomat that Alan could never be... Yet there was no question that naval Enigma was Alan Turing's and that he was in charge of it inasmuch as anyone else was. He had lived with it from beginning to end, and threw himself into the whole process, relishing the shift work on the incoming messages as much as any of the others." (13)

In December 1944 Hugh Alexander set up Naval Section IIJ specifically to make further inroads into the main Japanese naval code. (14) "Although GCCS was largely left to tackle virtually obsolete versions of JN 25, which OP-20-G, being the leader in this area, decided to bypass, Alexander still put his best into the work, and devised new Bayesian scoring methods to counter the increasing complexities of the code." In the summer of 1945 he spent about six weeks as the head of the code-breaking section of HMS Anderson in Colombo, where he helped to accelerate the supply of signals intelligence for the Eastern Fleet and to improve morale. (15)

Chess Champion

After the war Hugh Alexander returned to the John Lewis Partnership. However, he missed the world of cryptanalysis and in 1946 he rejoined the Government Code and Cypher School (GCCS), now renamed the Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ). He was promoted to head of section H (cryptanalysis) in 1949. He continued to play chess and was awarded the International Master title in 1950. At the Hastings International Chess Congress in 1953, he went undefeated and beat Soviet grandmasters David Bronstein and Alexander Tolush in individual games. Alexander was also chess correspondent of the Sunday Times, the Financial Times, the Evening News, and The Spectator.

Hugh Alexander died at Cheltenham on 15th February 1974. Alexander's activities at the Government Code and Cypher School remained a secret until Frederick Winterbotham published his book, The ULTRA Secret, later that year.

Primary Sources

(1) Hugh Alexander, Alan Turing, Gordon Welchman, and Stuart Milner-Barry, letter to Winston Churchill (21st October, 1941)

Some weeks ago you paid us the honour of a visit, and we believe that you regard our work as important. You will have seen that, thanks largely to the energy and foresight of Commander Travis, we have been well supplied with the 'bombes' for the breaking of the German Enigma codes. We think, however, that you ought to know that this work is being held up, and in some cases is not being done at all, principally because we cannot get sufficient staff to deal with it. Our reason for writing to you direct is that for months we have done everything that we possibly can through the normal channels, and that we despair of any early improvement without your intervention...

We have written this letter entirely on our own initiative. We do not know who or what is responsible for our difficulties, and most emphatically we do not want to be taken as criticising Commander Travis who has all along done his utmost to help us in every possible way. But if we are to do our job as well as it could and should be done it is absolutely vital that our wants, small as they are, should be promptly attended to. We have felt that we should be failing in our duty if we did not draw your attention to the facts and to the effects which they are having and must continue to have on our work, unless immediate action is taken.

(2) Hugh Alexander, quoted in Sinclair McKay, The Secret Life of Bletchley Park (2010)

There should be no question in anyone's mind that Turing's work was the biggest factor in Hut 8's success. In the early days, he was the only cryptographer who thought the problem worth tackling and not only was he primarily responsible for the main theoretical work within the Hut (particularly the developing of a satisfactory scoring technique for dealing with Banburismus) but he also shared with Welchman and Keen the chief credit for the invention of the Bombe... the pioneer work always tends to be forgotten when experience and routine later make everything seem easy and many of us in Hut 8 felt that the magnitude of Turing's contribution was never fully realised by the outside

world.

(3) Hugh Alexander, quoted in Alan Hodges, Alan Turing: the Enigma (1983)

He (Alan Turing) was always impatient of pompousness or officialdom of any kind indeed it was incomprehensible to him; authority to him was based solely on reason and the only grounds for being in charge was that you had a better grasp of the subject involved than anyone else. He found unreasonableness in others very hard to cope with because he found it very hard to believe that other people weren't all prepared to listen to reason; thus a practical weakness in him in the office was that he wouldn't suffer fools or humbugs as gladly as one sometimes has to.