John Edward Simkin (1883-1915)

John Edward Simkin, the only son and youngest child of Mary and John Edward Simkin senior (born 1842, Bromley), a storekeeper and factory labourer, was born in Limehouse on, 14th December, 1882.

In the 1901 census, John Edward Simkin junior is described as an "envelope cutter". He was living with his widowed father, a fifty-nine year old carman (probably a driver of a horse-drawn tram), at 22 Rich Street, Limehouse, Tower Hamlets.

In 1910, John Simkin married Jane Hopkins in Shoreditch. The couple's first child Elsie was born in 1912. She died in Islington three years later.

John Simkin was born on 17th January 1914 at No.13, Block B, Peabody's Buildings, Dufferin Street, Finsbury. At the time John Edward Simkin was working at the De La Rue & Company at their old established factory in Bunhill Row, Finsbury, London, known as the Star Works. A second son, William Valentine Simkin was born on 14th February 1915.

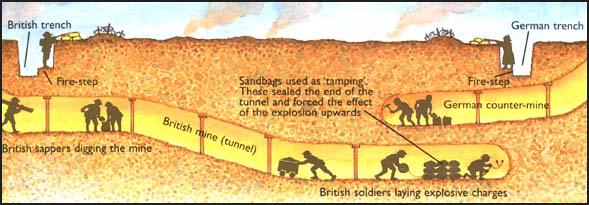

In the early stages of the First World War he joined the Royal East Kent Regiment. He arrived at Boulogne with the 7th Battalion in July 1915. When he reached the Western Front at the Somme he was attached to the 178th tunneling company. Where possible, the military employed specialist miners to dig tunnels under No Man's Land. The main objective was to place mines beneath enemy defensive positions. When it was detonated, the explosion would destroy that section of the trench. The infantry would then advance towards the enemy front-line hoping to take advantage of the confusion that followed the explosion of an underground mine.

Soldiers in the trenches developed different strategies to discover enemy tunnelling. One method was to drive a stick into the ground and hold the other end between the teeth and feel any underground vibrations. Another one involved sinking a water-filled oil drum into the floor of the trench. The soldiers then took it in turns to lower an ear into the water to listen for any noise being made by tunnellers. When an enemy's tunnel was found it was usually destroyed by placing an explosive charge inside.

It appears that John Simkin was involved in tunneling under the German frontline on 29th August, 1915, when a mine exploded and he was killed with two other men. Five others in the 178th tunneling company were badly injured.

John Edward Simkin was buried alive and his body has never been recovered. His name appears on the Thiepval War Memorial.

Primary Sources

(1) George Coppard, With A Machine Gun to Cambrai (1969)

Le Touquet consisted of a number of huge mine craters, roughly between the German front line and our own. In some cases the edge of one crater overlapped that of another. Companies of Royal Engineers, composed of specially selected British coal miners, worked in shifts around the clock digging tunnels towards the German line. When a tunnel was completed after several days of sweating labour, tons of explosive charges were stacked at the end and primed ready for firing. Careful calculations were made to ensure that the centre of the explosion would be bang under the target area.

This was an underground battle against time, with both sides competing against each other to blast great holes through the earth above. With listening apparatus the rival gangs could judge each other's progress, and draw conclusions. A continual contest went on. As soon as a mine was blasted, preparations for a new tunnel were started. On at least one occasion British and German miners clashed and fought underground, when the final partition of earth between them suddenly collapsed.

On the completion of one of the mines, the troops in the danger area withdrew when zero time for detonation was imminent. If the resultant crater had to be captured, an infantry storming party would be ready to rush forward and beat Jerry to it. Some of the craters measured over a hundred feet across the top, descending funnell-wise to a depth of at least thirty feet.

At the moment of explosion the ground trembled violently in a miniature earthquake. Then, like an enormous pie crust rising up, slowly at first, the bulging mass of earth crackled in thousands of fissures as it erupted. When the vast sticky mass could no longer contain the pressure beneath, the centre burst open, and the energy released carried all before it. Hundreds of tons of earth hurled skywards to a height of three hundred feet or more, many of the lumps of great size. A state of acute alarm prevailed as the deadly weight commenced to drop, scattered over a huge radial area from the centre of the blast.

(2) East Kent Regiment, 7th Battalion War Diary (29th August 1915)

News was received by the 7th Battalion that 3 men attached to the 178th Tunnelling Company were killed when a mine was blown in on 29th August 1915.

Student Activities

Walter Tull: Britain's First Black Officer (Answer Commentary)

Football and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

Football on the Western Front (Answer Commentary)

Käthe Kollwitz: German Artist in the First World War (Answer Commentary)

American Artists and the First World War (Answer Commentary)