|

The

History of Photography in Brighton

The

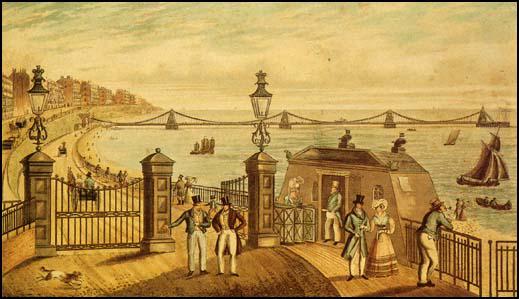

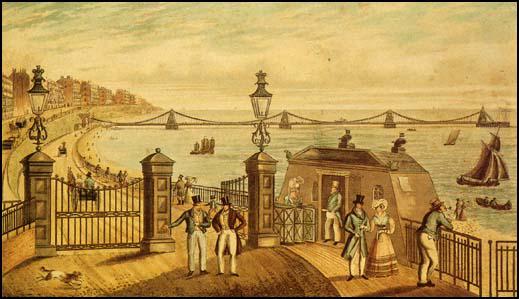

Chain Pier and Marine Parade, Brighton (c. 1830).Drawn and engraved

by John Bruce.

The

Chain Pier, Britain's

first seaside pleasure pier, was opened on 25th November 1823.

At top left can be seen the houses that lined Marine Parade. William

Constable's

Photographic Institution

was situated at No 57, to the left of the first pier tower.

PART

1: THE EARLY YEARS OF PHOTOGRAPHY IN BRIGHTON [ 1841-1854]

Section A :

The Beginning of Photography in Brighton ;

William

Constable and The Photographic Institution of Brighton

Brighton's

First Photographic Studio

Brighton’s first photographic studio opened on Monday 8th November

1841 at 57 Marine Parade, a large house situated on Brighton’s

eastern seafront. Two days later, the ‘Brighton Guardian’

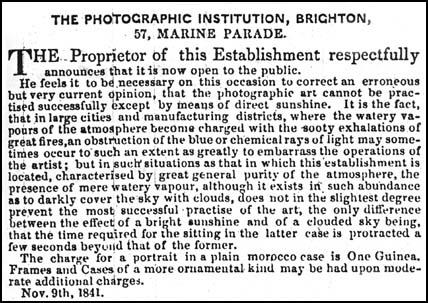

carried a notice dated 9 November 1841, in which “The Proprietor

of The Photographic Institution” at 57 Marine Parade announced

that his Establishment was now open to the public. [SOURCE

1] On the same page of the ‘Brighton Guardian’,

a correspondent of the newspaper welcomed the opening of the Photographic

Institution, which he believed would supply “what has been

long felt to be a great desideratum*

in society, - the means of securing a correct likeness without the

tedium of sitting for hours to an artist”

*desideratum = “a thing wanted

or desired"

William

Constable

Neither the article or the advertisement in the Brighton Guardian

of 10 November 1841 mentions the name of “The Proprietor”

of the Photographic Institution. The anonymous proprietor

was William Constable, a multi-talented

man, who at the age of 58 was entering a new field of enterprise,

which would draw upon those inventive skills which he had previously

demonstrated in the world of science, art and business.

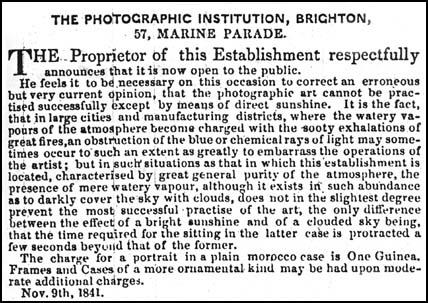

Advertisement

for William Constable's Photographic Institution ( Brighton Guardian

10 November 1841)

In the 1851 Census, William Constable gave his occupation as ‘Flour

Manufacturer and Heliographic Artist’, but this description

fails to reflect what had up to then been an extraordinary and colourful

career. A man without the benefit of an extended formal education,

William Constable had worked at various times as a successful high

street draper, an inventor of scientific devices, a watercolour

artist, cartographer, land surveyor, architect , bridge builder,

engineer, and the surveyor of a thirty mile stretch of the London

to Brighton Turnpike Road. [SOURCE

2] At an age when most men would be entering the last stage

of their working life, William Constable decided to embrace a new

technology and embark on a new career as a Photographic Artist.

Constable

in America

During

his lifetime, William Constable made a total of three visits to

America and it is possible that on his last trip to the States

in 1840, he had the opportunity to study the commercial possibilities

of the recently invented art of photography. Louis Jacques

Mande Daguerre, a French theatrical designer and showman had

perfected the technique of fixing an image on a silver-coated

copper plate in the late 1830s and the process had been announced

to the world in Paris in August 1839. This early form of photograph

was given the name daguerreotype by its inventor. The first

successful American daguerreotype was made in New York in September

1839 . Alexander Wolcott and his business partner John Johnson

opened the world’s first daguerrian portrait studio in New

York at the beginning of March 1840. Given Constable’s intellectual

curiosity and his fascination with scientific processes, it is

likely that he took an early interest in the new art of photography

and while in America he had the opportunity to observe the work

of early American daguerreotypists and see the commercial potential

of producing and selling photographic portraits.

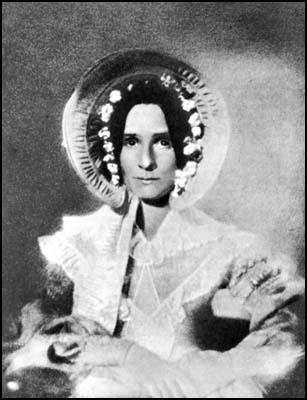

Miss Dorothy Draper,an American daguerreotype

portrait taken by John W Draper in June 1840

It

is therefore possible that when William Constable returned to

Brighton from America in 1841, he already had some knowledge of

the daguerreotype process. However, in the England of 1841 he

was not free to open his own independent photographic portrait

studio. In England, unlike other parts of the world, any person

who wished to establish a daguerreotype portrait studio first

had to acquire patent rights or purchase a licence from Richard

Beard, a prosperous businessman who since 1840 had taken steps

to take control of this new commercial enterprise.

Richard

Beard and the Daguerreotype Patent in England

1 Portrait

of Richard Beard (1801-1885) Portrait

of Richard Beard (1801-1885)

Richard

Beard opened England's first photographic portrait studio

in London on 23rd March 1841 and made a fortune selling daguerreotype

licences.

|

Richard

Beard, a successful coal merchant, and patent speculator,

had seen the advantages of securing a monopoly in the production

of daguerreotype portraits in England. In June 1840, Beard

filed a patent which included the features of Alexander S

Wolcott’s mirror camera which, by drastically reducing

exposure times, would make the production of photographic

portraits more effective. Beard then employed the services

of John Frederick Goddard, a chemist and lecturer in science

who had been experimenting with various chemicals to sensitize

the silvered plates in an effort to accelerate camera exposure

times. Early in 1841, Goddard produced a mixture of iodine

and bromine to increase the sensitivity of the photographic

plates, thereby reducing exposure times to less than a minute

or, in bright sunlight, to a number of seconds. On 23rd March

1841, Richard Beard opened England’s first photographic

portrait studio to the public at the Royal Polytechnic Institution,

309 Regent Street, London. In June 1841, Beard concluded his

negotiations with Miles Berry, Louis Daguerre’s patent

agent in England, and purchased the patent rights to the daguerreotype

process. On 16th July 1841 Beard signed an agreement with

Daguerre and the son of Nicephore Niepce, the man who

had made the first successful photograph from nature in 1826.

|

By

the end of July 1841, Beard had become the sole patentee of the

daguerreotype process in “England, Wales and the town of Berwick

on Tweed, and in all Her Majesty’s Colonies and Plantations

abroad” and had a virtual monopoly in the production of photographic

portraits using Daguerre’s method.

Beard’s

only serious rival in the field of daguerreotype portraiture in

1841 was Antoine Claudet, a French glass

merchant living in London,who had made direct contact with Daguerre

in France and had secured from the inventor a licence to make daguerreotype

portraits in London.

Until

the patent rights of British Patent No 8194 expired on 14th August

1853, any person who wanted to legally carry out the art of daguerreotype

portrait photography on a commercial basis had to apply to Richard

Beard, to either purchase the right of patent in a prescribed geographical

area or to purchase a licence to work the process in a particular

town or city.

England's

First Provincial Photographic Studios

In June 1841, Richard Beard claimed to have “disposed of licences

for Liverpool, Brighton, Bristol, Bath, Cheltenham and Plymouth”.

The first provincial photographic studio in England was opened on

31st July 1841 at Plymouth. A second daguerreotype studio was opened

in Bristol on 10th August 1841. In September, 1841 Photographic

Institutions were established at Cheltenham and Liverpool. On

Saturday 2nd October, Alfred Barber opened a photographic portrait

studio in Nottingham. The proprietors of these new “Photographic

Institutions” required considerable capital. To operate in

the town of Nottingham, Alfred Barber was expected to pay a total

of £1,220, made up of a down payment of £450, a first

instalment of £50, followed by three separate quarterly instalments

of £240. The Licence which covered Liverpool and a ten mile

area around the city was fixed at £2,500.

|

William

Constable's Photographic Institution in Brighton

William

Constable had paid £1,000 to Beard for a licence to

take daguerreotype portraits in Brighton. Constable opened

his Photographic Institution to the public on Monday 8th November

1841. Before

the week was over, Constable wrote to his sister Susanna and

gave a progress report on his new enterprise:

“I opened my concern of business last Monday –

for the first day or two I took but very little money indeed

. . . I could not help feeling anxious and nervous, although

the result was what I reasonably ought to have expected –

But I feel every day that I am growing in notice and have

no doubt that I am gaining a very fast and respectable foothold

here . . . I am crowded with visitors all day – from

11 to 4 . . . there is nothing against me but the lateness

of the season.”

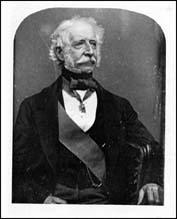

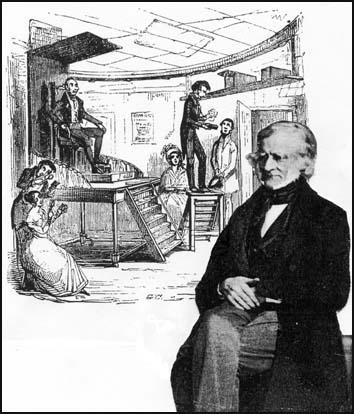

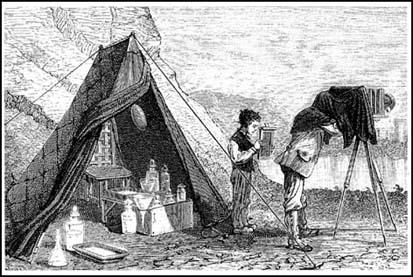

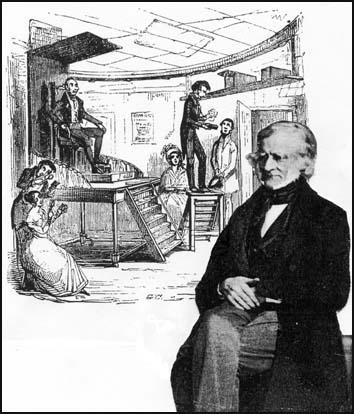

William Constable seated in front of

Cruikshank's 1842 picture of an early daguerreotype studio.

|

1  |

Seasonal

Visitors to Brighton

Constable’s phrase ‘the lateness of the season’ could

be assumed to be a reference to the darkening skies of winter, when

an absence of sunshine would lengthen camera exposure times and

affect the quality of his studio portraits, but he was probably

expressing his concern that the season of the year when it was fashionable

to visit Brighton was nearing its end. Twenty years earlier the

aristocracy and the upper classes of society had traditionally visited

Brighton in the summer months of June, July and August. The ‘Brighton

Ambulator’ of 1818 had calculated there were 7000 additional

residents in Brighton during the summer months between June and

October, but from November to February the number of visitors declined

to 2,300. By 1830, the fashionable season had shifted from the summer

to the autumn and winter.

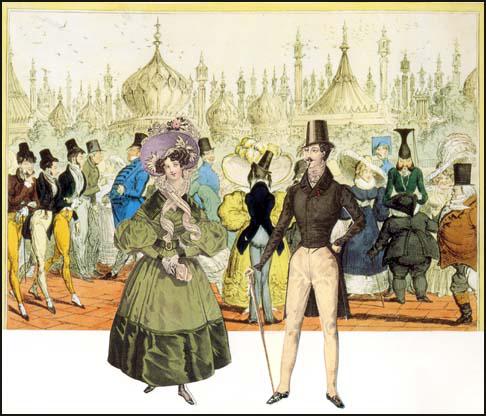

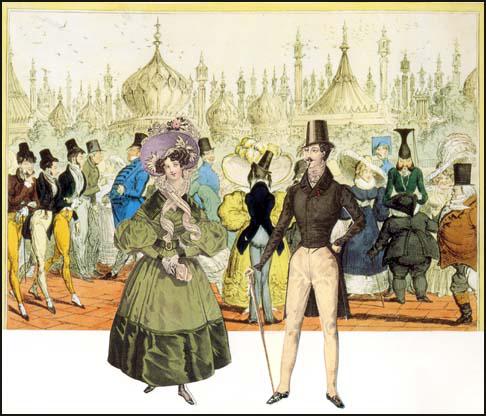

Fashionable Visitors to Brighton.

.

A fashionable couple with Alfred Crowquill's Beauties of Brighton

(1826) in the background.

Even before the railway line from London to Brighton was completed

in September 1841, the ‘New Monthly Magazine’ had

declared :

“the summer months are abandoned to the trading population

of London, the early autumn is surrendered to the lawyers and when

November summons them to Westminster, the ‘beau monde’

commence their migration to encounter the gales of that inclement

season secure from any participation of the pleasure with a plebian

multitude”.

Constable's

Photographic Portraits of Prince Albert and the Nobility

Constable had established his exclusive portrait studio in Brighton

at a time when the nobility and gentry were delaying their visits

to Brighton, restricting their period of stay at this fashionable

seaside resort to the months of November, December and January.

As Edmund M Gilbert commented in his study of Brighton and the growth

of the English seaside resort, the aristocracy found that “residence

in Brighton could be deferred until after the departure of the vulgarians”.

1 ,. ,.

Copy of a daguerreotype portrait

of Prince Albert [1842] Attributed to William Constable's

Photographic Institution. John Counsell, one of Constable's

assistants, claimed to have operated the camera when

Prince Albert sat for his portrait in Brighton on 7th

March, 1842.

|

The

Royal Family chose to visit Brighton even later in the season,

perhaps to avoid the fashionable visitors. Queen Victoria,

her consort Prince Albert, their two young children, Victoria

the Princess Royal and Albert Edward, the Prince of Wales

and members of Court took up residence at the Royal Pavilion

on 10th February 1842. On 25th February, George Anson, Prince

Albert’s Private Secretary, visited Constable’s

Photographic Institution on Marine Parade and had his portrait

taken. Just over a week later, on 5th March 1842, Prince

Albert himself, together with two German cousins, arrived

at Constable’s studio unannounced hoping to have their

portraits taken but, as Constable’s sister Mrs Susanna

Grece later recalled, the day was an "unlucky

one for portrait taking"

and the Prince and his cousins “like others this day

could not get a good picture”.

The

next day, Prince Albert’s German relatives Prince Ferdinand

of Saxe-Coburg and his two sons Prince Augustus and Prince

Leopold sat for their portraits and as later reported in

the Sussex Express “expressed their astonishment at

the rapidity of the process and the fidelity of the likenesses.”

Encouraged

by their response, Prince Albert called in at the Photographic

Institution on the afternoon of 7th March in order to be

photographed. According to the journal of Constable’s

sister, Susanna Grece, Prince Albert posed a number of times

that afternoon, but with limited success. “He had eight

pictures, not all good”. The successful daguerreotypes

were later photographed and two carbon prints have survived.

These two small portraits of Prince Albert, dated 1842 and

attributed to Constable, are believed to be the earliest

surviving photographs of a member of the Royal Family.

|

The

royal visit would have helped to establish William Constable’s

reputation as a photographer to the aristocracy and members of the

Court. Over the next ten years his sitters included the Duke of

Devonshire, the Marchioness of Donegal, Lord Cavendish and the Grand

Duchess of Parma. As Constable noted in 1848 “I have had many

sitters from the ranks that are called noble”.

A daguerreotype portrait of Sir Hugh

Gough taken in 1850 by an unknown photographer. Born in

1779, Gough fought with Wellington in the Napoleonic Wars.

|

A portrait miniature of a young officer

by the artist George Engleheart [1750-1829]. When Sir Hugh

Gough ( far left

) was an officer in Wellington's Army in the early

part of the 19th Century, a visit to a portrait painter was

the only way to secure a good likeness. By the time he was

in his early sixties, Gough, like other wealthy men, could

turn to a daguerreotype artist to make a small photographic

portrait.

|

Constable's Successful Photographic Studio

Constable

had been fortunate to secure Royal patronage and his aristocratic

and noble clients saw him safely through his first two years of

business at Marine Parade. However, Constable was an astute businessman

and was prepared to take steps to ensure a steady flow of sitters.

When Constable opened his Photographic Institution in November 1841,

he charged one guinea (£1.1s or 1.05p) for a portrait in a

plain morocco leather case. His prices are comparable to those charged

by other Beard Licencees of the period. Prices in the West End of

London were rather higher. Beard's own Polytechnic Studio in Regent

Street London charged upwards from £1 8s 6d (about £1.42p)

for a small daguerreotype portrait.

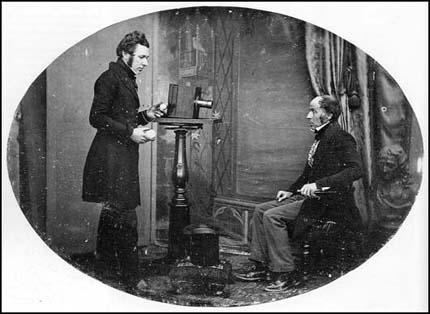

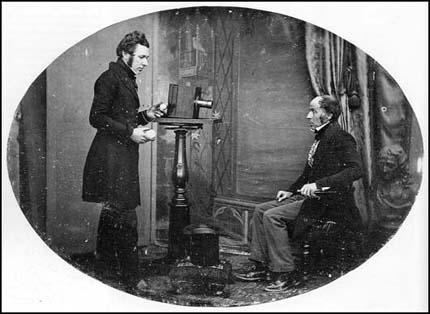

Jabez

Hogg, an operator for Richard Beard, taking a daguerreotype portrait

of Mr Johnson in London (c1842)

Running a Photographic Institution in the 1840s could be lucrative,

but it was a risky business. Within two months of opening to the

public in September 1841, the Liverpool studio had taken 500 portraits.

However, in Nottingham, Alfred Barber had taken only 53 portraits

over a four month period and when he failed to keep up his quarterly

payments, Beard took legal action to close Barber's studio. Constable

feared that the prices he charged his exclusive clientele would

deter other potential customers. By the end of 1843, he had reduced

his price for a cased portrait from £1.1s (£1.05p) to

12s 6d (62p), hoping "to possess himself of the patronage of

the middle classes of the community." A daguerreotype portrait

was still out of the reach of ordinary working people. An unskilled

worker would earn less than 10 shillings (50p.) a week in the 1840s.

However, reducing the price of his daguerreotype portraits meant

that his customer base was widened to embrace wealthy visitors and

Brighton's expanding middle class. The Dukes, Earls, Lords and Ladies

who made up Constable's early clientele were joined by prosperous

merchants, successful businessmen and professional gentlemen together

with their wives and children.The addition of customers drawn from

the middle ranks of society ensured that Constable had no shortage

of sitters in the late 1840s.

William Constable is known to have employed operators at his Photographic

Institution on Marine Parade from the very beginning.Constable's

sister, Mrs Susanna Grece, mentions in her journal that her brother

employed at least two assistants in 1842. John Counsell,

who later became a daguerreotypist in Edinburgh and Cornwall, claimed

to have made the portraits of Prince Albert and the Duke of Saxe

Coburg at Constable's Marine Parade studio in March 1842. The photographic

artist James Thomas Foard, who went on to manage Beard's

Liverpool studio in 1849, had worked for William Constable five

years earlier.

Very few of the original proprietors of the provincial Photographic

Institutions licensed by Beard stayed in business for very long.

The Photographic Rooms in the Horticultural Gardens of Bristol changed

hands at least 3 times between 1841 and 1848. John Palmer, an early

Beard licensee, vacated the Cheltenham Photographic Institution

in 1844 after only 3 years. In contrast, William Constable remained

in business as a Photographic Artist in Brighton for 20 years from

November 1841 until his death in December 1861.

Section

B: Daguerreotype and Talbotype; Early Photographic Artists in Brighton

[1851-1854]

DAGUERREOTYPE PORTRAIT STUDIOS IN BRIGHTON

Holding an exclusive licence from Richard Beard, William Constable

had a virtual monopoly in the production of photographic portraits

in Brighton between November 1841 and 1851. In the Census of 1851,

the only other photographer recorded in Brighton was nineteen year

old Thomas B.Leffin, who was presumably an assistant to William

Constable. The 1851 Census describes Constable as "Flour

Manufacturer and Heliographic Artist ", a widower aged 67,

living with two nieces, Caroline and Eliza Constable,

who probably provided assistance in his photographic business. After

William Constable died in December 1861, a Miss Constable continued

to run his studio at 58 King's Road.

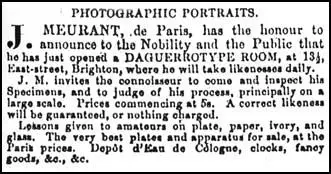

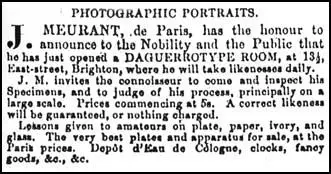

Advertisement

for Joseph Meurant's Daguerreotype Room (Brighton Herald

7August 1852)

At least on one occasion, a daguerreotype artist felt confident

enough to challenge Constable's monopoly in the production of daguerreotype

portraits in the town . In the Summer of 1852, a rival to Constable

appeared in the form of a French daguerreotype artist, Joseph

Meurant from Paris. In July 1852, Meurant announced in the

'Brighton Herald' that he had opened a Daguerreotype Room at 131/2

East Street, where he offered to take likenesses for as little as

5 shillings. Meurant remained in Brighton for less than nine months

before moving on to London. [Shortly after Beard's patent on the

daguerreotype expired in 1853, Meurant established a photographic

studio at Newington Butts in South London.]

EARLY PHOTOGRAPHIC VIEWS OF BRIGHTON

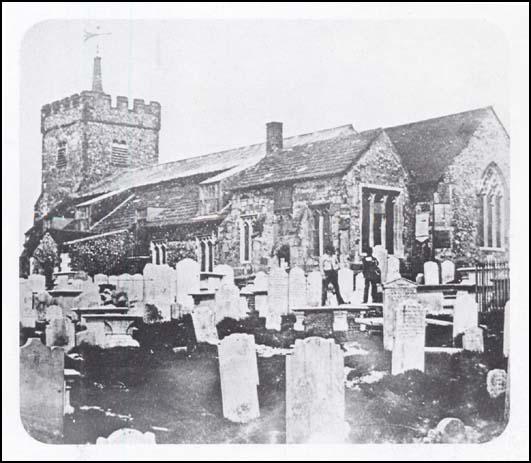

St

Nicholas' Church (c1850). A daguerreotype by George Ruff senior

Before the arrival of Meurant in 1852, there is no record of any

professional portrait photographers in Brighton who could compete

against William Constable. However, there is evidence that there

were other "photographic artists" making daguerreotypes

and early photographic views of Brighton between 1850 and 1852.

George Ruff, described as a 24 year old "painter in

oil and watercolour" in the 1851 Census, was using daguerreotype

apparatus to capture local views and buildings around this time.

George Ruff, who painted landscapes and marine scenes, made a daguerreotype

of Brighton's St Nicholas Church around 1850 and it is likely he

made other daguerreotypes, either as an aid to his landscape painting

or as 'works of art' in their own right. Edward Fox junior, who

specialised in landscape photography, was the son of a London born

waterolour artist who had settled in Brighton around 1820. Edward

Fox junior, also described himself as an artist and in the 1850s

he earned his living as a decorative painter and designer. By the

early 1860s, Fox was advertising his landscape photography and in

his later advertisements mentions that he had "given his whole

attention to Out-door Photography since 1851." Edward Fox was

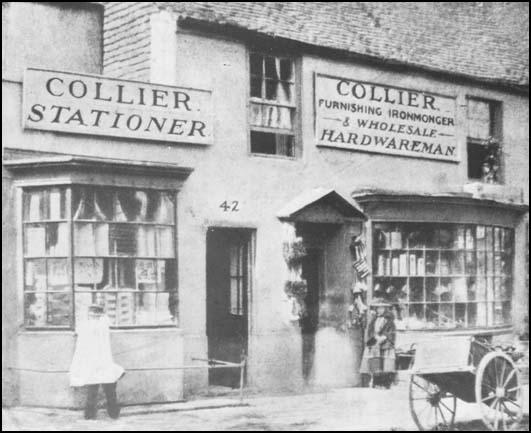

based at 44 Market Street and a photograph believed to date from

around 1851 shows the neighbouring shops at Nos 42 and 43 Market

Street.

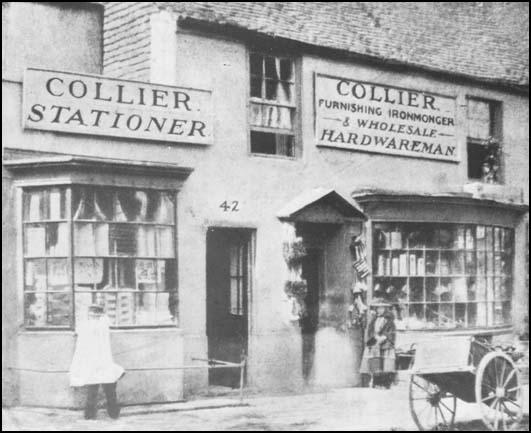

Numbers

42 and 43 Market Street, Brighton (c1851). The photographer is not

named, but Edward Fox junior, lived at 44 Market Street and was

taking photographic views of Brighton as early as 1851.

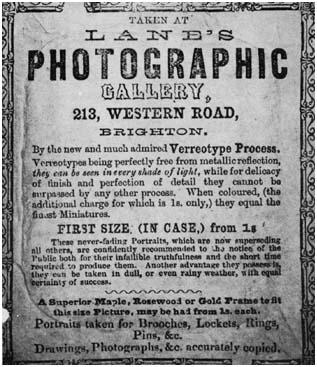

DAGUERREOTYPE ARTISTS IN BRIGHTON AFTER 1853

After Beard's Daguerreotype Patent expired in August 1853, a number

of Brighton trades people, who had already shown an interest in

the art of photography, set up their own daguerreotype portrait

studios.As early as 1852, William Lane, proprietor of 'Lane's

Cheap Picture Frame Manufactory', established a Photographic Depot

at 3 Market Street, Brighton where he supplied "Daguerreotype

Lenses, Camera Apparatus" and "every other requisite used

in Photography." A complete set of apparatus for the daguerreotype

process cost 7 guineas at Lanes' Depot.In an advertisement which

appeared eight days before Beard's daguerreotype patent was due

to expire, William Lane was offering to supply 'Daguerreotype Apparatus'

to operators and amateurs promising free instruction in the Photographer's

Art to purchasers of materials. By November 1853, Lane had set himself

up as a photographic artist and was offering to provide "a

first class daguerreotype portrait in handsome French case for two

shillings" at his new premises at 213 Western Road.

Robert Farmer, who had taken over William Passmore's Chemist's

shop at 59 North Street in 1852, transformed part of his new business

premises into Daguerreotype Rooms - which included "a room

designed and built expressly with apparatus of very superior construction

for the purpose . . . to ensure a fine portrait." In newspapers

issued in November 1853, Robert Farmer publicized his Daguerreotype

Rooms and "invited the attention of the Ladies, Gentlemen and

Visitors to Brighton to his collection of Photographic Portraits,

taken plain or in colours, by competent Artists". Mr Farmer

offered to take "fine portraits" at moderate prices -

"1s 6d in case; or coloured 2s 6d" which would have been

considerably lower than those charged by William Constable's Original

Photographic Institution in Marine Parade.

The Talbotype - an alternative to the Daguerreotype

in Brighton

In 1839, the same year that Daguerre announced his method of fixing

images on a silvered copper plate, William

Henry Fox Talbot,

an English landowner, scholar and scientist published 'The Art of

Photogenic Drawing', an account of how he had managed to capture

images permanently on paper. Four years earlier, Talbot had produced

tiny photographic views of Lacock Abbey, his home in Wiltshire.

By treating the small pictures with wax, Talbot was able to use

them as negatives and print further copies. Although he had invented

a negative/positive photographic process, Talbot's early pictures

were small, required very long exposure times and lacked the sharpness

of detail and brilliance of the daguerreotype. Talbot continued

his experiments and improved the quality of his photographs by coating

his paper with silver iodide and developing the images with a gallo-nitrate

of silver solution. Talbot patented his new process in February

1841, describing his pictures as 'Calotypes'. Talbot protected his

photographic inventions by filing a number of all-embracing patents.

Under pressure from the Royal Academy and the Royal Society, Talbot

had, in August 1852, relaxed his control over the production of

calotypes, allowing amateurs and artists to use the process,

but he insisted that all professional photographers who wanted to

use his calotype process for taking portraits had to purchase a

licence, which usually involved an annual fee of between £100

and £150.

In 1852, Thomas Henry Hennah, a young London artist, together

with William Henry Kent, a photographic artist from the Isle

of Wight, purchased a licence from William Fox Talbot to make portraits

using the calotype process. The photographic prints were called

'Talbotypes' in honour of the inventor. By 1854, Hennah and Kent

had established a Talbotype Portrait Gallery in William Henry

Mason's Repository of Arts at 108 King's Road, Brighton.An

item in the 'Brighton Gazette' of 12th October 1854 indicates that

the Talbotype Gallery specialised in taking portraits of the nobility

and the upper ranks of society. The 'Brighton Gazette' enumerates

"a few of the distinguished persons who have recently honoured

these eminently skilful artists with a sitting", listing the

Duke of Devonshire, Countess Granville, Lord Carnworth, Lady Keats

and several other notable visitors to Brighton. Hennah & Kent

came into direct competition with William Constable who in July

1854 joined forces with another daguerreotype artist, Edward

Collier at 58 Kings Road to form the firm of Constable &

Collier.

Robert Farmer, who made his living mainly from taking daguerreotype

portraits, placed advertisements during November and December of

1853, which drew attention to his "Calotype views of the Pavilion,

The Railway Terminus etc taken by Gustave Le Gray's new waxed paper

process." [Farmer's advertisement would have annoyed William

Fox Talbot who claimed Le Gray's waxed paper process was an infringement

of his patent of 1843.]

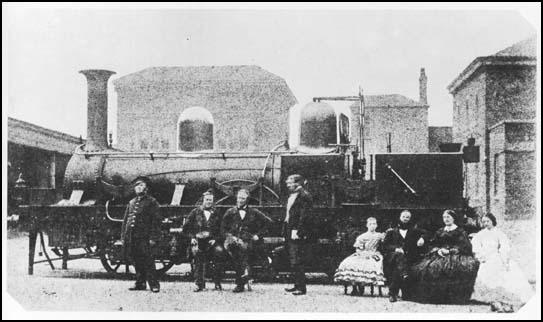

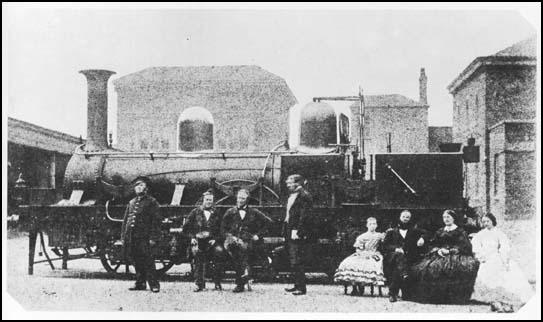

Craven's

Locomotive No12 with John Chester Craven,his family and staff at

Lover's Walk,Brighton (May 1858) A talbotype had less detail than

a daguerreotype and the print often had a fuzzy and mottled appearance.

Stephen Grey and William Hall, who established their

General Photographic Institution at 13 St James Street in the summer

of 1854, offered to take portraits "by all the most recent

and improved processes by 'Licence of the Patentees'. Large sized

Talbotype portraits mounted in a gilt frame were offered at 15 shillings

(75p), while daguerreotype portraits were priced from 6 shillings

(30p).

Amateurs and artists who wished to use Talbot's invention could

turn to Lewis Dixey, optician and mathematical instrument

maker of 21 Kings Road, Brighton, who supplied "every description

of photographic apparatus for the Calotype" and iodized paper

for the Talbotype.

PART

2: PHOTOGRAPHS ON GLASS AND PAPER [ 1854 - 1860 ]

Section

A : The Collodion Process

and Photographs on Glass

In

March 1851, Frederick Scott Archer, a sculptor and a member

of the Calotype Photographic Club, published details of his "wet

collodion process", which involved coating a glass plate

with a mixture of potassium iodide and a sticky substance called

collodion. Also known as "gun cotton", collodion was a

transparent and adhesive material that was first used in surgery

to dress wounds. The coated glass plate was then sensitized in a

bath of silver nitrate. The highly sensitive wet plate was then

placed inside a camera and exposed by uncapping the lens. Earlier

methods using glass plates coated with albumen (egg white) provided

exposure times of between five to fifteen minutes and so were unsuitable

for portrait photography. Archer's "wet collodion" process

could produced high quality negatives after exposures of only a

few seconds. Unlike Beard with the daguerreotype process and Talbot

with the 'calotype', Archer chose not to patent his discovery and

offered his invention free to all photographers.

Collodion

Positives - Cheap Portraits on Glass

Frederick Scott Archer's collodion 'wet plate' process produced

a glass negative which could make an unlimited number of prints

on paper. However, most customers were seeking a cheap alternative

to the handsome daguerreotype portrait, which came protected under

glass in a metal frame and presented in a velvet-lined, leather-bound

display case. Scott Archer soon realised that by underexposing the

collodion glass negative and placing it on a black background, the

image took on the appearance of a positive picture.The resulting

image was as sharp and clear as a daguerreotype, yet Archer's new

process was cheaper and less complicated. Furthermore, the collodion

positive process was incredibly quick to perform. Photographers

could see immediately the commercial possibilities of a cheap and

speedy method of taking portraits. The "collodion positive"

photograph on glass could be backed with black paper, very dark

varnish or provided with a background of black velvet or similar

dark cloth. Protected by glass, placed in a metal frame and inserted

in a presentation case or an elaborate frame, the collodion positive

was an inexpensive substitute for the daguerreotype portrait, which

in the 1840s had been the preserve of the nobility and the wealthy

middle classes of society.

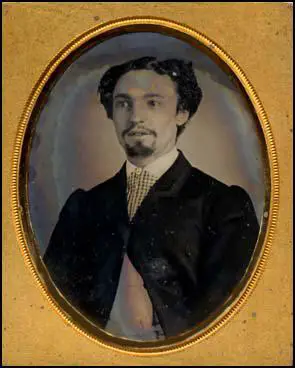

A

Portrait of a Bearded Man. A collodion positive photograph on glass

taken by George Ruff senior (c1858). The presentation case is similar

to the ones that held daguerreotype portraits.

William Lane of Brighton was promoting the new process of making

"portraits and views taken on glass" as early as September

1852. In an advertisement placed in The Times, dated 10th September

1852, Lane claimed that "any person can produce in a few seconds,

at a trifling expense, truly life-like portraits."Early

in 1853, William Lane's Cheap Photographic Depot was offering a

"complete set of apparatus for the glass or paper process"

for the sum of 4 guineas (£4. 4s/£4.20p). By October

1853, The Royal Chain Pier Photographic Rooms in Brighton

were advertising "Portraits superior to engravings by the new

process on glass."

On 3rd August 1854, Grey & Hall's Photographic Institution

on St James Street announced they had "completed arrangements

for taking portraits by all the most recent and improved processes,

by License of the Patentees". In addition to Talbotype portraits

and "Daguerreotypes warranted to last," Grey and Hall

offered to make "Coloured Collodion Positives by a new

and peculiar process" for the sum of 15 shillings (75p).

Stephen Grey and William Hall were keen to emphasize

that their new methods of taking portraits were "licensed by

the Patentees". Archer had not patented his invention and Beard's

daguerreotype patent had expired the year before, but William Henry

Fox Talbot claimed that the "collodion process" was covered

by his earlier patent which had described a negative/positive system

of photography.

In 1854, W.H.Fox Talbot took legal action against the studio of

Silvester Laroche,the professional name of Martin Laroche, a London

photographer who had started to use Archer's "wet collodion"

technique in 1853. Silvester Laroche went to court to defend his

right to use the "wet plate" process. In December 1854,

Laroche was found not guilty of infringing Talbot's patent rights

and as a result of this legal judgement all photography was now

free from restriction.

In the summer of 1855, James Henderson, a photographic artist

who had previously operated portrait studios in London's Strand

and Regent Street, opened a photographic studio at No 5, Colonnade

in New Road, Brighton. In an advertisement dated 4th August 1855,

James Henderson offered to take "Photographic Portraits, on

Paper, Silver, and Glass Plates . . . Prices from 10s 6d and upwards."

In this newspaper advertisement, Henderson "begs to remind

all lovers of Photography that he has been at considerable expense

in defending the freedom of this beautiful art against Mr Fox Talbot,

the Patentee of the Talbotype process." Earlier, in May 1854,

Talbot had obtained an injunction which restrained Henderson from

making and selling photographic portraits by the collodion process.

Laroche's successful defence against Talbot's legal action meant

that Henderson and other photographers in Brighton were free to

produce portraits using any of the main photographic processes.

Section

B : A Variety of Photographerss

The

Artist - Photographer

The earliest photographer in Brighton, William Constable

had, before turning to photography, received some attention for

his artistic talent in drawing and painting. During his travels

in America, Constable made sketches of Niagara Falls and other

striking features of the New World, which he later made into finished

watercolours. A contemporary newspaper The Brightron Herald

described Constable's artwork as "eminently fresh, graphic

and original". Modern commentators on Constable's photographs

draw particular attention to their artistic quality.

An

artist turns to the art of photography.[ Interior with

Portraits (c1865) by the American artist Thomas Le Clear]

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTE

Many

of Brighton's early photographers had an artistic background.

George Ruff gave his occupation as "Painter in Oil

and Water Colours" in the 1851 Census and as an artist, exhibited

marine and landscape paintings before he set up his photographic

studio in Brighton's Queens Road. Edward Fox junior was

described as a "decorative painter" in the census and

Jesse Harris, who was describedl as a daguerreotype artist

in 1854, is recorded in the 1851 Census as "Artist-Painter".

Stephen Grey, who joined with William Hall to form the

photographic firm of Grey & Hall in 1854, is listed

as a portrait painter in an 1852 directory. Thomas H. Hennah,

a partner in the Hennah & Kent photographic studio,

gave his profession as "artist" to the census enumerator.

Chemists

and Opticians

Photography has its technical as well as artistic aspects. The

early photographic processes were complicated and required the

agency of chemicals and so it is not surprising that an early

Brighton photographer was the chemist Robert Farmer, who

had come to Brighton in 1852 to take over William S. Passmore's

chemist's shop at 59 North Street. Photography also involves optics

and the employment of lenses and so Lewis Dixey, optician

and mathematical instrument maker of Kings Road, Brighton was

well placed to provide photographic apparatus and by 1854 he was

also listed as a daguerreotype artist.

Carvers,

Gilders and Picture Frame Makers

It was perhaps natural for carvers, gilders and picture frame

makers to become involved in the new art of photography. William

G. Smith who became a photographic artist in the mid 1850s

was a carver and gilder residing in Western Road Brighton at the

time of the 1851 Census. William Lane had owned the 'Cheap

Picture Frame Manufactory' at 3 Market Street, near Castle Square,

Brighton, where he mounted and framed paintings, engravings and

water colour drawings. As early as 1852, Lane had added to his

picture framing business a Photographic Apparatus Depot. William

Lane described himself as a photographer in 1852, but he had few

artistic pretensions. He took a more practical approach than photographic

artists such as Constable, Fox, Harris, Hennah and Ruff. According

to William Lane's 1852 advertisement, artistic talent was not

a prerequisite for accomplished photography."No knowledge

of drawing required to produce these wondrous works of art and

beauty... By this new process any person can produce in a few

seconds (at a trifling expense) truly life-like portraits of their

friends, landscapes, views, buildings etc". Lane offered

to provide "printed instructions, containing full particulars

for practising this fascinating art with ease and certainty".

Artisans

and Tradesmen

William

Lane was happy to supply daguerreotype apparatus and materials

to operators or amateurs, providing "instructions in the

Photographic Art" free of charge to all purchasers of photographic

equipment.

By the late 1850s, tradesmen with no previous interest in art

or photography had set themselves up as photographic artists.

Possibly armed with apparatus and instructions from Wiliam Lane's

Photographic Depot or some other local supplier, two brothers

Charles and John Combes, established themselves as "daguerreotypers"

at 62 St James Street, Brighton in 1854. In 1851, Charles Combes

was employed as a warehouseman and his younger brother John was

learning shoemaking from his cordwainer father. The Combes brothers

obviously believed they could improve their fortunes by entering

a potentially lucrative business.

James

Waggett, was earning a living manufacturing and tuning pianofortes,

when he decided to offer the additional service of taking photographic

portraits. After 3 years or so, James Waggett was removed from

the list of Brighton photographic artists and appeared once more

under the heading 'pianoforte tuners' in the local trades directory.

The chosen trade of James R Bates was that of fruiterer

and seedsman. As a 23 year old, he was running a fruiterer's shop

in Brighton and forty years later he was still in the same business.

Yet, for at least a year from 1858 to 1859, James R Bates tried

his hand at photography. When the expected profits did not materialise,

Bates abandoned photography and returned to selling fruit, seeds

and flowers.

Entrepreneurs

Joseph Langridge was a true entrepreneur. Langridge was

prepared to invest in any sort of scheme and ready to carry out

any trade to make money, and he eventually realised that taking

photographic portraits was as good a way as any. In his twenties,

Joseph Langridge, the son of a pawnbroker and second hand clothes

dealer, borrowed heavily to purchase railway shares, and invest

in a jewellery business. He carried on as a jeweller in Brighton

until the late 1840s when he started a bakery business in London.

Langridge was an insolvent debtor in 1842 and nine years later,

after his bakery venture failed, he was again declared insolvent

and sentenced to 10 months imprisonment for not paying off his

debts. On his release from prison, Langridge tried his hand at

manufacturing soda water and, by 1853, he was selling smoked and

salted herrings as 'Brighton bloaters'. Listed as a photographer

at 43 Clarence Square Brighton in 1858, Joseph Langridge was probably

the man behind the photographic firm of Merrick & Co,

which appeared at 186 Western Road in 1856. Under the studio name

of Merrick, Joseph Langridge continued as a photographic artist

in Brighton for another sixteen years.

Emigres,

Exiles and Foreign Professors

Mrs

Agnes Ruge has the distinction of being the first woman to

be recorded as a photographer in Brighton. Madame Ruge is listed

at 180 Western Road under the heading of Daguerreotype Artists

in W J Taylor's 1854 Directory of Brighton. Agnes Ruge, who was

born in Dresden, Saxony, arrived in England in 1850 and was one

of several emigres who practised photography in Brighton. Joseph

Meurant, who was originally from Paris, had opened a Daguerreotype

Room In East Street, Brighton in July 1852.

Agnes

Ruge was the wife of Professor Arnold Ruge (1802-1880), an associate

of Karl Marx and a radical, who had been driven into political

exile after the failure of the 1848 Revolution in Germany.Mrs

Ruge worked as a daguerreotype artist for only a short period

of time. By 1857, Agnes Ruge was earning a living as a teacher

of the German language. Karl Marx wrote in November 1857 that

"Mrs Ruge is the only teacher of German in Brighton"

and added that "so greatly does demand exceed supply,"

she had to recruit her 19 year old daughter,Hedwig, as an assistant.

In

1851, Sarah Lowenthal was described as a "Preceptress",

or teacher, at a Ladies' School in Brighton. Mrs Lowenthal was

the English wife of Nathan Lowenthal, a Prussian immigrant , who,

in the 1851 Census, gave his occupation as "Professor of

Languages." In 1856, Mrs Sarah Lowenthal is listed in a local

directory as a "Talbotype Portrait Colourer" based at

Lonsdale House, College Road, Brighton.

High Street Photographers from London

PART

3 : THE GROWTH OF PHOTOGRAPHIC STUDIOS IN BRIGHTON ( 1854-1861

)

Photographic

Portrait Studios

In the ten years between November 1841 and November 1851, William

Constable, aided by a few assistants, was the only photographic

artist operating a portrait studio in Brighton.

When W.J.Taylor's Original Directory of Brighton was compiled

for the year 1854, ten photographic studios were listed :

Edward COLLIER 58, King's Road

Charles and John COMBES 62, St James's Street

William CONSTABLE 57, Marine Parade

Lewis DIXEY 21, King's Road

Robert FARMER 59 & 114 North Street

GREY & HALL 13, St James's Street

Jesse HARRIS 213, Western Road

HENNAH & KENT 108, King's Road

William LANE 213, Western Road

Madame Agnes RUGE 180 Western Road

All the photographers listed in Taylor's 1854 directory appeared

under the heading 'ARTISTS - Daguerreotype', yet we know Hennah

& Kent specialised in talbotypes, Lewis Dixey stocked

photographic apparatus for the calotype and collodion processes,

Farmer produced calotypes using a waxed paper process and Grey

& Hall employed "three distinct processes" - talbotype

and collodion as well as daguerreotype.

To the 10 studios listed by Taylor's Directory in 1854 we can

add the names of the artists Edward Fox junior and George

Ruff, both of whom were using a camera to make views of Brighton

in the early 1850s.

William Constable, who for 10 years had enjoyed a monopoly

in the production of photographic portraits, was now faced with

up to a dozen competitors. In the summer of 1854, Constable closed

his original studio at 57 Marine Parade and removed his photographic

business to the Old Custom House at 58 King's Road, where he joined

forces with the daguerreotype artist Edward Collier. The

Partnership of Constable & Collier continued for about

3 years. By 1858, William Constable was listed as the sole proprietor

of the Original Photographic Institution at 58 Kings' Road.

In June 1855, the Brighton and Sussex Photographic Society

was formed. The Photographic Society held monthly meetings and

was open to amateurs and professionals. An amateur, the Reverend

Watson acted as chairman, while the post of Honorary Secretary

was held by Constable's business partner and professional daguerreotype

artist Edward Collier. By September 1855, the Photographic Society

boasted 40 members.

James Henderson, a well known London daguerreotype artist,

arrived in Brighton in the summer of 1855, but by September he

had moved on to Cornwall, to establish a portrait studio in Launceston.

Henderson may have been deterred by the number of photographers

already active in Brighton. Folthorp's Brighton Directory, which

had been corrected to September 1856, adds three more photographic

studios not listed in Taylor's earlier directory. George Ruff,

who had been taking daguerreotype since around 1850, finally presented

himself as a professional photograher in 1856. Also listed in

1856 was the firm of Merrick & Co and James

Waggett, who had previously operated as a manufacturer

and tuner of pianofortes at 193 Western Road. Photographic artists

were listed in the section on Professions and Trades in Brighton

directories, but these listings do not provide a complete picture.

William G Smith is described as a photographic artist in

the 1856 street directory, but his name does not appear as a photographer

in the 'professions and trades' directory. William Lane,

an important name in the early history of photography in Brighton,

is not listed in Folthorp's Directory of 1856, yet newspaper advertisements

from this time show that William Lane was employing two other

operators, Mr Davis and Mr Warner, and in addition to his main

studio at 213 Western Road, Lane had a branch studio in Shoreham.

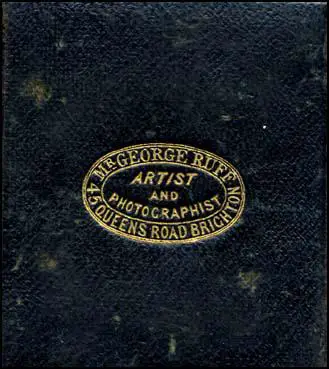

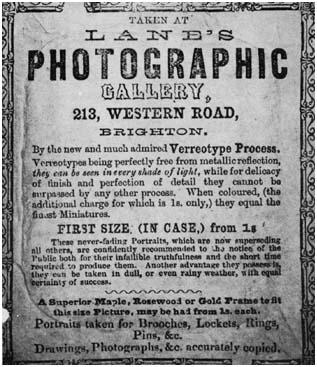

Portrait

of a Boy (c1855). "Verreotype" portrait taken at Lane's

Photographic Gallery, 213 Western Road. William Lane called his

collodion positives "verreotypes". In America they were

known as "ambrotypes".

The

Decline of the Daguerreotype

By the time Folthorp's Directory of 1856 was published, the daguerreotype

was on its way out. All the photographers listed in the Professional

and Trades section of Folthorp's Directory appear under the heading

Photographic and Talbotype Galleries. 'Farmer's Daguerreotype

Rooms' had become 'Farmer's Photographic Institution' and William

Lane had abandoned the daguerreotype for his Verreotype process.

In an advertisement dated 3 January 1856, William Lane

promoted his new and improved Verreotype Process, by detailing

the advantages the new process had over the daguerreotype. Verreotypes,

Lane proclaimed, were perfectly free from metallic reflection

and could be seen "in every shade of light." Verreotype

portraits took only a short time to produce and could be "taken

in dull, or even rainy weather . . . when it would be quite impossible

to operate with the Daguerreotype method." Lane states confidently

in his advertisement that "these never fading Portraits .

. . are now superseding Daguerreotypes."

Stereoscopic

Photographs

In

1838, the English scientist and inventor Sir Charles Wheatstone

(1802-1875) had described the phenomena of binocular vision and

designed apparatus which fused two separate drawings into a single

three dimensional image. To describe this viewing instrument,

Wheatstone coined the term "Stereoscope" (from the Greek

words 'stereos' meaning "solid" and 'skopein' meaning

"to look at") With the advent of photography, Wheatstone's

reflecting stereoscope, which utilised mirrors, could be used

to view a pair of almost identical photographs and give the illusion

of depth.

Sir David Brewster (1781-1868), a Scottish physicist, designed

a stereoscope that employed two lenses which mimicked binocular

vision. Jules Duboscq (1817-1886) a Parisian optician constructed

an improved stereoscope based on Brewster's design, which merged

two photographs of the same subject to form a three-dimensional

picture.

At the Great Exhibition of 1851, Queen Victoria was particularly

impressed by Duboscq's stereoscope and the accompanying stereoscopic

photographs. Queen Victoria's interest in the stereoscope

signalled the start of a popular demand for stereoscope viewers

and stereoscopic photographs. In 1856, Brewster reported over

half a million of his stereoscopes had been sold.

A few stereoscopic talbotypes had been made for Wheatstone soon

after the introduction of photography in 1839. In the early 1850s,

however, most of the early stereoscopic photographs were daguerreotypes.

Duboscq had displayed a set of his own stereoscopic daguerreotypes

at the Great Exhibition of 1851. In 1853, Antoine Claudet

patented a folding stereoscope which could view stereo daguerreotypes.

A couple of years after the Great Exhibition of 1851 stereoscopic

photography arrived in Brighton. In 1853, Thomas Rowley,

Optician to the Sussex and Brighton Eye Infirmary, was advertising

his "superior selection of stereoscopes with Daguerreotype

plates, Collodion and Photographic Pictures" which could

be hired from his premises at 12 St James Street. In November

1853, Robert Farmer of the Daguerreotype Rooms, 59 North

Street was offering to provide a "stereoscopic Portrait,

with Stereoscope, 10s 6d, complete." Lewis Dixey,

Optician and Dealer in Photographic Apparatus, announced in 1854

that he could supply "Stereoscopes & Stereoscopic subjects

in Calotype, Daguerreotype & Collodion or Glass." George

Ruff of 45 Queens Road, Brighton specialised in stereoscopic

portraits in colour.

Stereo Cards

The reflective surface of a silvered copper plate was not ideal

for stereoscopic effects and the process did not lend itself to

the manufacture of large quantities of stereo pictures. With the

advent of the collodion glass negative and photographic prints

on albumenized paper in the mid 1850s, the mass production of

stereo cards became possible.

The London Stereoscopic Company, founded in 1854 by George

Swan Nottage, was a firm that specialized in the mass production

of stereoscopic photographs. Nottage's company responded to the

enormous demand for stereoscopes and stereo cards. By 1856, The

London Stereoscopic Company had sold over 500,000 stereoscopes

and had 10,000 titles in its trade list of stereo cards. Two years

later, in 1858, The London Stereoscopic Company claimed to have

100,000 stereo cards in stock [ George Swan Nottage (1823-1885)

had connections with Brighton. He owned property in the town and

was a regular visitor to Brighton. At the time of the 1861 Census

George Swan Nottage was residing at 15 Marine Parade, Brighton

and when he died in April 1885, he had just returned from an Easter

holiday at the seaside town.]

In 1857, The Brighton Stereoscopic Company based at 121

St James Street, near the Old Steine was selling stereoscopes

from half a crown (2s 6d/121/2 p) and stereoscopic views were

on sale at a shilling (1s/10 p) each.

The fashion for collecting and viewing stereoscopic photographs

reached its peak in the early 1860s. In 1862 alone, The London

Stereoscopic Company had sold a milliion stereoscopic views.

A wide variety of stereoscopic images could be purchased - views

of faraway places, (Japan, The Andes) scenes of everyday life,

anecdotal pictures, humorous tableaux scenes, 'still life' arrangements

and pictures of life in town and country.In 1858, Samuel Fry,

a photographic artist based at 79 Kings Road, Brighton,even produced

a "Stereograph of the Moon"

Some of the stereoscopic views sold in Brighton were of purely

local interest.

In March 1863, William Cornish junior of 109 Kings Road,

Brighton was advertising a set of six stereoscopic photographs

of a decorated railway shed. The 531 ft. long railway shed was

used to house 7,000 school children who had gathered for a meal

to celebrate the marriage of Edward, Prince of Wales and Princess

Alexandra of Denmark. Stereoscopic views of the decorated railway

shed could be purchased singly for one shilling (10 pence) or

the customer could buy a complete set for 6 shillings

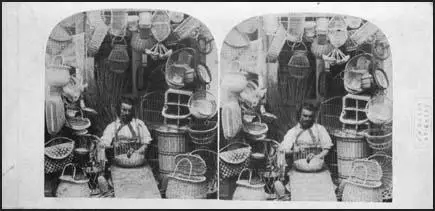

William Mason junior, the son of W.H.Mason, printseller

and proprietor of the Repository of Arts in Brighton's Kings Road,

photographed scenes featuring local craftspeople, such as basketmakers,

and issued them as stereographic cards.

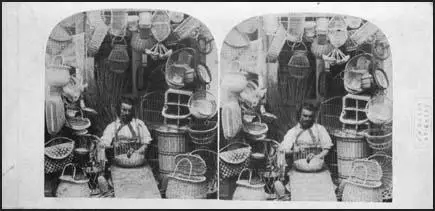

Stereocard

of a Brighton Basketmaker by W H Mason junior (c1862)

More typically, the Brighton artist Edward Fox, who specialised

in landscape photography, advertised "local views as stereoscopic

slides." Familiar landmarks in Brighton, such as the Royal

Chain Pier and the Royal Pavilion became popular subjects for

stereo cards.Some of Edward Fox junior's stereoscopic slides featured

particularly dramatic scenes. Fox's titles included " The

Chain Pier During a Gale " and " Chain Pier by Moonlight".

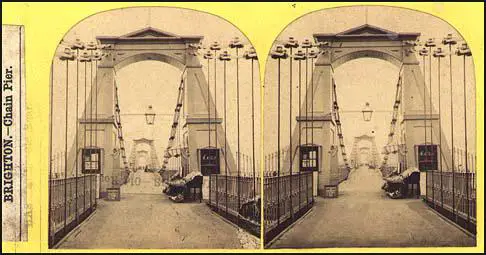

Stereocard of the Chain

Pier, Brighton c1870

Albumen in Photography

Albumen is a clear,organic material found in its purest form in

the white of an egg. Smooth, transparent and sticky, albumen was

seen as a suitable binder in photography. In 1847, the French

army officer and chemist Abel Niepce de Saint-Victor (1805-1870),coated

glass plates with egg-white mixed with potassium iodide and then

sensitized the dried plates in a bath of silver nitrate. The albumen-coated

glass plates made fine, photographic negatives, but exposure times

ranged from five to fifteen minutes and so were only really suitable

for photographing landscapes or buildings. Albumen glass negatives

were soon superseded by Fred Scott Archer's collodion glass negatives.

The Albumen Print

In 1850, L. D. Blanquart-Evrard (1802-1872), a French photographer,

introduced albumenized paper for photographic prints. Albumen

from the white of an egg was mixed with sodium chloride. Sheets

of thin paper were coated with the albumen mixture and then sensitized

with silver nitrate. A collodion glass negative could produce

finely detailed photographs on albumenized paper. By the 1860s,

most photographers were using collodion glass negatives and albumenized

paper in the production of photographic prints.

Blanquart-Evrard exhibited his albumen prints at the Great Exhibition

of 1851, announcing that his new process made it "possible

to produce two or three hundred prints from the same negative

the same day." The albumen print became an essential

component for the mass production of photographic images and played

an important part in meeting the public demand for stereographic

cards and carte de visite portraits in the 1860s.

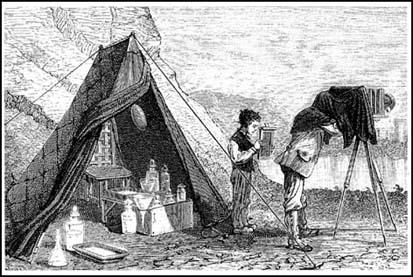

Outdoor Photography

When Joseph Nicephore Niepce created the earliest surviving

photograph in 1826, the materials he used were so insensitive

it took 8 hours of sunlight for the image to be fixed on the pewter

plate he had prepared. Niepce's heliograph ('sun drawing') was

a view of his courtyard, taken from a top floor window. In 1839,

when photography was first introduced to the world, camera exposure

times ranged from five to fifteen minutes and so the only suitable

subjects were buildings, landscapes and arrangements of still

life. The majority of the pictures made by L.J.M.Daguerre himself

are of buildings and views in Paris.

Artists and amateurs may have been content to use the new invention

to produce a pleasing landscape or record an interesting building,

but astute businessmen knew that financial reward and commercial

success would lie in portrait photography. Every effort had been

made to reduce camera exposure times so that the daguerreotype

process could be used to make portraits. By the early 1840s technical

advances in photography meant that a sitter would only have to

hold a pose for a number of seconds rather than a number of minutes.

When Richard Beard, the patentee of the daguerreotype process

in England and Wales, sold licences authorising the setting up

of 'Photographic Institutions' in provincial towns, the purchasers

were mainly interested in using the invention to "take likenesses."

Outdoor Photography in Brighton Before

1854

The journalist who in November 1841 welcomed the opening of William

Constable's 'Photographic Institution' on Marine Parade in the

pages of the Brighton Guardian, recognised that the main purpose

of photography was to secure "a correct likeness without

the tedium of sitting for hours to an artist."

William Constable made his living from taking "likenesses",

charging his customers one guinea for "a portrait in a plain

morocco case", but it is known that he occasionally took

his camera on to the streets of Brighton. In the 1840s, Constable

took views of fashionable houses in Kemp Town, and two daguerreotypes

of houses in Lewes Crescent ended up in the photograph collection

of Richard Dykes Alexander.

In the early 1850s, local artists Edward Fox junior and

George Ruff senior were taking photographs of buildings

in Brighton. Ruff made a daguerreotype of St Nicholas Church around

1850 and Edward Fox, who declared in later advertisements that

he had "given his whole attention to Out-Door Photography

since 1851", produced pictures of shop fronts, churches and

other public buildings in Brighton and the surrounding area. In

1853, Robert Farmer, proprietor of the 'Daguerreotype Rooms'

in North Street, Brighton was exhibiting his calotype views of

the Royal Pavilion and the Railway Terminus and daguerreotype

views of Brighton's oldest church.

The

West Battery, Kings Road (c1850)

Outdoor Photography in Brighton 1855-1862

With the advent of the collodion process, more and more photographers

in Brighton were taking their cameras out on the street to record

life in the town.

Old buildings and structures scheduled for demolition were a favourite

subject for photographers, who were anxious to record them for

posterity. For example, a battery of eight guns was established

in Brighton's West Cliff in the 1790s to protect the town from

French attacks by sea. In 1857, it was decided to remove the West

Battery so that Brighton's main thoroughfare, the King's Road,

could be widened. Work commenced in January 1858 and from this

date a series of photographs recorded the progress of the dismantling

of the battery and the breaking up of the artillery ground.

In 1862, a row of old houses and shops that ran from 41 to 43

North Street, was scheduled for demolition. A set of oval shaped

photographs recorded the shop fronts and the rear ends of the

buildings that were to be demolished. It is not clear exactly

why these photographs were commissioned, but they allow us to

glimpse not only a vanished parade of Victorian shops, but also

a few bystanders, some of whom would not have been able to afford

the services of a photographer. Another gorup of workers whose

wages probably would not stretch to pay for a sitting at the professional

portrait studio, are captured on a photograph showing the entrance

ot the premises of Palmer and Company, Engineers and Iron Founders.

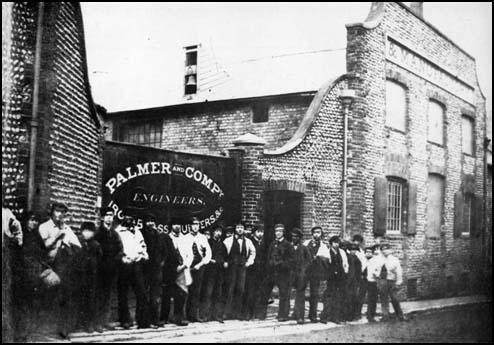

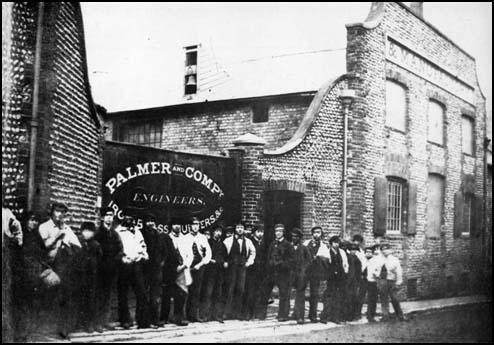

Workers

employed by Palmer & Co.Engineers stand

outside the company's premises in North Road. (c1865)

PART 5 :THE CARTE DE VISITE

CRAZE ( 1862-1870 )

The

Carte de Visite Format

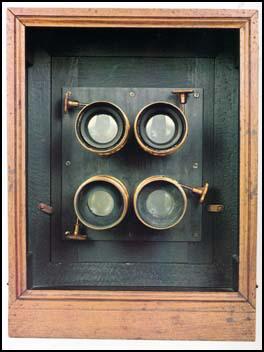

In the early 1850s, a number of French photographers put forward

the idea of mounting a small photographic portrait on a card the

same size as the customary calling card. In 1854, a Parisian photographer

called Andre Adolphe Disderi (1819-1889) devised a multi-lens

camera with a collodion plate that could be moved to capture between

four and twelve small portraits on a single glass negative. This

meant that a photographer equipped with a camera with four lenses

could take a total of eight portraits, in a variety of poses,

all on one camera plate. From the resulting negative, the photographer

could produce a set of contact prints on albumenized paper, which

could then be cut up and pasted on to small cards. The card mounts

were the same size as conventional visiting cards (roughly 21/2

inches by 41/4 inches or 6.3 cm by

10.5 cm) and so this new format of photograph came to be known

as 'carte de visite' - the French term for visiting card.

|

|

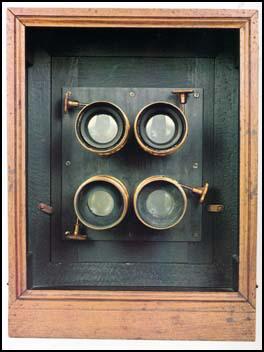

LEFT:An

early carte de visite camera. RIGHT: An

uncut sheet of 8 carte de visite portraits by Disderi. c1862

C

In 1857, Marion and Co, a French firm of photographic dealers

and publishers, introduced the carte de visite (cdv) format

to England. By 1859, the carte de visite portrait was fashionable

in Paris, but the new format was not immediately popular in this

country.

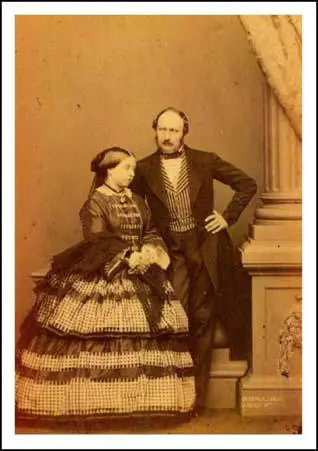

Celebrity Cartes

In May 1860, John Jabez Edwin Mayall, who was later to

open a photographic studio in Brighton, made a number of portraits

of the Royal Family. Mayall was given permission to publish the

portraits of the Royal Family as a set of cartes-de-visite. In

August 1860, the cartes were released in the form of a Royal Album,

comprising of 14 small portraits of Queen Victoria, Prince Albert

and their children. The Royal Album was an immediate success,

and the cartes sold in their hundreds of thousands.

LEFT:Queen

Victoria and Prince Albert by J J E Mayall (1861) One of the royal

portraits that was issued as a cdv.

RIGHT

:A page from The Royal Album, which featured cdv portraits

of the Royal Family by Mayall (1861)RIGTL

The

publication of a set of royal portraits started a fashion in Britain

for collecting carte de visite portraits of famous people. Another

series of royal portraits by Mayall was published in 1861. In

the December of that year, Queen Victoria's husband Prince Albert

succumbed to typhoid fever and his death created an enormous demand

for his portrait. The Photographic News later reported that within

one week of his death "no less than 70,000 of

his carte de visite were ordered from Marion & Co."

By the end of the decade, Marion & Co, had paid Mayall £35,000

for his portraits of the Royal Family.

Leading photographers made portraits of the famous personalities

of the day, which were then issued in carte de visite (cdv)

format and sold through retail outlets such as print sellers,

stationers, booksellers and fancy goods shop. The retail trade

dealt with cdv portraits of statesmen, politicians, actors, authors,

artists, entertainers and other famous people. By 1861, Thomas

Hill, who sold all manner of fancy goods at his shop at 66 East

Street, Brighton, was selling 'Albums for the Carte de Visite'

and had in stock a "great variety" of these celebrity

portraits.

Local Celebrity Cartes

In the early 1860s, Brighton studios were advertising cartes de

visite of local celebrities. William Hall, a former partner

in the photographic firm of Grey & Hall and now the sole proprietor

of the studio at 13 St James Street, was one of the first photographers

in Brighton to promote celebrity cartes. In a newspaper advertisement

dated 27th February 1862, Hall offered to the public cdv portraits

of "Eminent Ministers - taken from life." Hall

listed 20 church ministers who were featured in his cdv portraits,

including the Reverend T. Trocke of Chapel Royal and Reverend

J.L.Knowles of St Peter's Church.

In September 1862, the photographic firm Merrick & Co

of 33 Western Road, was offering for sale, at 1s 6d a copy, a

cdv portrait of 'The African Princess' who had married Mr.James

Davis at Brighton the previous month.

Portraits for the Masses

A portrait made by either the daguerreotype or collodion positive

process was unique and copies could only be made by re-photographing

the original. Disderi's carte de visite method meant that one

negative whole-plate could hold up to eight individual images.

This eight picture negative could then be used repeatedly to produce

multiple copies. A photographer could therefore produce eight

small portraits at one sitting and from a single negative produce

a large number of prints, thereby greatly reducing the cost of

each portrait. When William Hall was in partnership with

Stephen Grey at 13 St James Street in 1854 a small daguerreotype

portrait could be had for 6 shillings ( 30 p.) In 1862, at the

same studio, William Hall was offering to provide a dozen

cdv portraits at a price of 12 shillings ( 60 p.). High class

photographic establishments such as Mayall's new portrait studio

at 90-91 King's Road Brighton, priced a set of twelve cdv portraits

at £1.1s (£1.05p) when the studio opened in July 1864.

Hennah & Kent, another quality portrait studio in Brighton,

"got 21/- a dozen for cartes" according to A.H.Fry,

who worked for the studio in the early 1860s. At the other end

of the scale, The West-End Photographic Company, based

at 109 Western Road Brighton was charging 5s (25 p.) for twelve

cartes de visite in 1864. At the same studio a single cdv portrait

would cost 1 shilling ( 5 p.), three copies could be had for 2

shillings (10 p.), while six copies could be purchased for 3s

(15 p.)

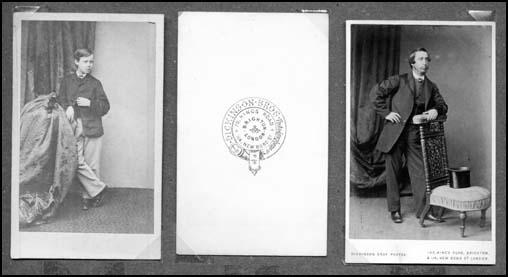

Carte de visite portraits

from Brighton photographic studios : HAWKINS; BOTHAM ;COMBES

Carte de visite portraits

from Brighton photographic studios::LOCK

& WHITFIELD; CONSTABLE; CLARK

Carte de visite portraits

from Brighton photographic studios::GREY;

MERRICK; DOLIBO:

In the 1860s, every High Street photographer in Brighton recognised

the fact that the carte de visite (cdv) was the most popular

of the portrait formats. The cdv also generated the most income.

It is reported that J J E Mayall produced over half a million

cartes a year, which helped him secure an annual income of £12,000.

In December 1861, The Photographic News declared "At

the present time, we believe cartes de visite are the most renumerative

class of portraits produced by professional photographers."

The Photographic News pointed out that the cdv's profitability

stemmed from the fact they were "generally ordered in

quanitities." The cdv itself became an advertisement

and generated business. As The Photographic News explained:

"each one sent out is a recommendation and almost certainly

brings fresh customers. Thus a sitter orders a dozen copies; in

giving these to his friends, he places each one, to a certain

extent under the obligation of giving a portrait in return; and

thus it happens that every portrait taken becomes, as it were,

the nucleus of a fresh order."

"Cartomania"

With

the growing popularity of the cdv portrait, High Street photographers

experienced an increased demand for their services. A top London

studio could expect, on average, around 30 sitters a day, although

in the summer months the figure could be higher. In May 1861,

Camille Silvy's London studio recorded 806 customers for that

month alone. A provincial photographer reported that "fifteen

in a morning was considered a good day's work, although in the

summer it often rose to twenty-five."

Benjamin Botham arrived in Brighton to set up a photographic

portrait studio around 1861. When he decided to sell his studio

seven years later in order to begin a new career as the proprietor

of the Oxford Theatre of Varieties, he passed on nearly 10,000

negatives to his successor.

The demand for carte de visite portraits led to a further

growth in the number of portrait studios in Brighton.In

1858, there were around 16 photographic studios in Brighton. By

1862, when the carte de visite craze was taking off, the number

of portrait studios in Brighton had risen to 21. Lane's Photographic

Portrait Rooms at 213 Western Road became the photographic studio

of The Carte de Visite Co., with William Lane acting

as manager. At the height of the cdv craze in 1867, there was

a total of 37 studios in Brighton, most of which were supplying

cdv portraits.

High Street Photographers from London

The

1860s saw the arrival of large London firms intent on establishing

branch studios in Brighton.

Dickinson Brothers was a leading firm of printers and publishers

based at 114 New Bond Street. The company had achieved national

recognition for a set of 55 large, coloured lithographs, entitled

'Comprehensive Pictures of the Great Exhibition of 1851',

which illustrated the various display areas at the Crystal Palace.

By 1855, Dickinson Brothers had become interested in photography

and had established two photographic portrait studios in London,

one at their premises in New Bond Street and the other at 174

Regent Street. Dickinson Brothers established a branch studio

at the prime site of 70-71 Kings Road, Brighton around 1862. Lowes

and Gilbert Dickinson carried on their photographic portrait business

in Brighton until 1868, when the demand for carte de visite portraits

had begun to decline.

Around

1862 the London firm of Dickinson Brothers established a photographic

studio at 70 Kings Road, Brighton. By 1867, Dickinson Brothers

had moved their photographic portrait studio to 107 Kings Road,

Brighton, next door to Hennah & Kent at No 108, and Lock &

Whitfield at 109 Kings Road.

1864 saw the arrival of two companies which had already established

a reputation for high class portrait photography in London's fashionable

Regent Street - J J E Mayall and Lock & Whitfield.

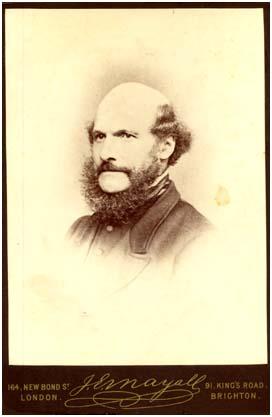

Lancashire born John Jabez Edwin Mayall (1813-1901) the

son of a manufacturing Chemist and Dye Works proprietor, had begun

his working life near Huddersfield, West Yorkshire, but around

1842, he travelled to America to study the art and science of

photography under the tutelage of two scientists attached to the

University of Pennsylvania. In 1844, Mayall entered into partnership

with Samuel Van Loan and together they operated a daguerreotype

portrait studio in Philadelphia. A few years later, Mayall returned

to England and by April 1847 he had established a Daguerreotype

Institution at 433, West Strand, London. By 1852, Mayall had opened

a second studio at 224 Regent Street in the West End of London.

Mayall had secured the patronage of Queen Victoria and the Royal

Family and between 1860 and 1862, he published sets of royal portraits

in the carte de visite format, which triggered a craze for collecting

cdv portraits. Mayall achieved fame and fortune. In the year 1861,

he reportedly made £12,000 from his carte de visite portraits.

Leaving

his eldest son Edwin to run his London studios, John J.E.Mayall

moved down to Brighton with his wife and two younger sons

and on 18th July 1864, he opened his new photographic portrait

studio at 90-91 Kings Road, close to the recently built Grand

Hotel. In an announcement placed in the pages of the Brighton

Examiner, Mayall declared that he had "spared neither pains

nor expertise in preparing, for the accommodation of the nobility

and gentry resident at or visiting Brighton, one of the most efficient

studios ever built." Although he addressed his comments particularly

to the "nobililty and gentry", Mayall admitted that

he was "not unmindful of the fact . . . that moderate charges

are as necessary as general excellence to ensure extensive public

patronage." Mayall charged £1.1s (£1.05p) for

a set of 12 carte de visite portraits and £5.5s (£5.25p)

for his "highly finished" coloured portrait photographs.

More modest establishments in Brighton were offering a dozen carte

de visite portraits for 5 shillings (25 p.) in 1864.

Mayall made the guarantee that his new Brighton studio would be

"as successful in operation as it is complete in design".

Mayall's name remained on the Kings Road Studio until 1908, seven

years after his death. Mayall, who lived in the Brighton area

until he died in Southwick on 6th March 1901, involved himself

fully in the life of the town and became active in local politics

and in 1877 he was made Mayor of Brighton.

Lock

& Whitfield, Photographers and Miniature Painters of 178

Regent Street, London established a branch studio at 109 Kings

Road, Brighton in 1864, a few months after Mayall opened his studio

on the same fashionable highway.

Samuel Robert Lock (1822-1881) was an artist who in the

early 1850s was converting talbotype portraits into painted miniatures.

In September 1856, he joined forces with George C.Whitfield

(born c.1833) who had recently built a photographic portrait

studio in London's Regent Street.

In an advertisement placed in a Brighton newspaper, dated 20th

September 1864, Lock & Whitfield offered to take "carte

de visite and every description of photograph, colored or uncolored

(sic), on paper, ivory or porcelain."

Lock & Whitfield was in direct competition with the

other firms from London, Mayall and the Dickinson Brothers, which

also had their studios on Brighton's Kings Road. By 1867, Lock

& Whitfield had fixed the price of twenty carte de visite

portraits at £1.1s.6d (roughly £1.06p.)

Lock & Whitfield probably employed a manager to run their

Brighton studio in the 1860s, but by the time of the 1871 Census,

George C Whitfield was living at Upper Rock Gardens, Brighton

with his wife and five children. Samuel Lock took up residence

in Brighton in 1877, but died 4 years later on 9th May 1881. Lock

& Whitfield's Brighton studio at 109 Kings Road was taken

over by another chain of photographers, Debenham & Co

in 1886.

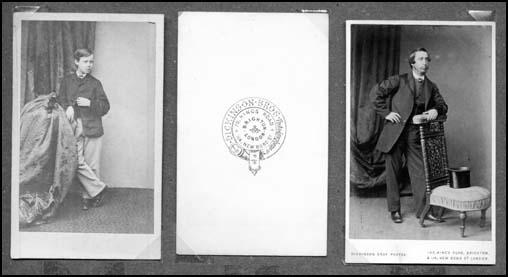

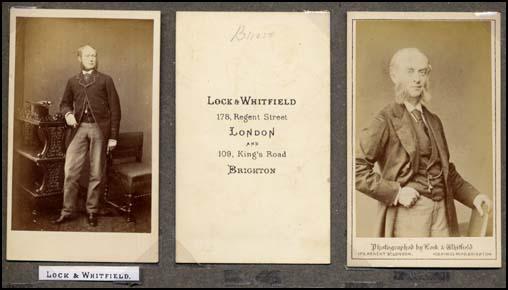

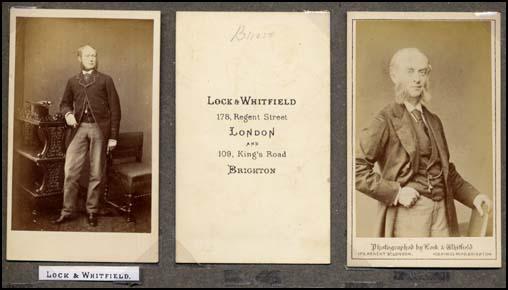

Carte

de visite portraits taken in Brighton by the London firm of Lock

& Whitfield. After they established a studio in Brighton at

109 Kings Road in 1864, the partners continued to operate a portrait

studio in London at 178 Regent Street.The studio in Regent Street

carried the name of Lock & Whitfield until around 1895.

The

Cabinet Format

In 1866, Frederick Richard Window, a London photographer

who had introduced the Diamond Cameo Carte de Visite two years

earlier, put forward the idea of a larger format for portrait

photography. The proposed format was a photographic print mounted

on a sturdy card measuring 41/4 inches by

61/2 inches. (roughly 11cm x 17cm). The

new format was called the Cabinet Portrait, presumably

because a large photograph on a stout card could be displayed

on a wooden cabinet or similar piece of furniture. The Scottish

photographer George Washington Wilson (1823-1893) had produced

'cabinet' sized landscape views as early as 1862, but F.R.Window

had adopted the large format specifically for portraiture.

Window believed the larger dimensions of the 'cabinet print' (4

inches by 51/2 inches

or approximately 10.2 cm x 10.2 cm x 14.1 cm) would enable the

professional photographer to demonstraste his technical and artistic

skill and produce portraits of a higher quality than the small

cdv would allow.

The cabinet photograph increased in popularity as the demand

for carte de visite portraits fell. Much larger than the cdv,

the size of the cabinet format made it more suitable for group

and family portraits.

|

Carte de visite portrait