Charles Luard

Charles Edward Luard, was born in Leith on 13th October 1839. His father Robert Luard was at the time serving as a captain in the Royal Artillery. Charles, like his father and grandfather, joined the British Army.

In July 1875, Charles Luard married Caroline Hartley, who was twelve years younger than her husband. Over the next few years Caroline gave birth to two sons: Charles (5th August 1876) and Eric (6th April 1878).

He served in the Royal Engineers and was involved in several building projects including the United Services Recreation Ground in Portsmouth and the Household Cavalry Barracks at Windsor. He also served overseas in Corfu, Gibraltar, Bermuda and Natal.

Charles Luard retired on 21st October 1887 with the honorary rank of Major General. The following year they moved to Ightham Knoll, a house situated just outside the village of Ightham. Luard was appointed a Justice of the Peace and was elected to serve on Kent County Council.

Both their sons joined the British Army. However, in 1903, Eric Luard died from a fever contracted while serving in the Somaliland campaign.

On 24th August, 1908, the couple left their home at 2.30. Charles Luard destination was Godden Green Golf Club as he needed to collect his golf clubs for a weekend trip away. Caroline Luard only went part of the way with her husband as she was expected the arrival of Mrs Mary Stewart, the wife of a retired solicitor, at 4.00.

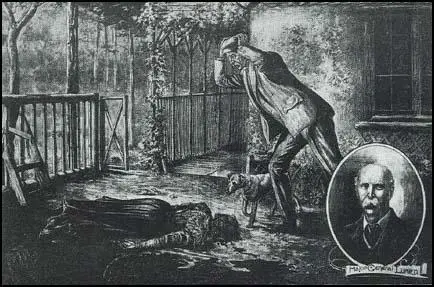

Charles Luard, who got a lift from the Reverend Arthur Cotton, arrived back at Ightham Knoll at 4.30 to find that his wife was not at home. After having tea with Mary Stewart the couple went in search of Mrs. Luard. He eventually found her body at the La Casa summer-house at 5.30. She had been shot twice in the head. A purse and four rings were missing.

The inquest was held at Ightham Knoll on 26th August, 1908. Some people complained about the inquest being held in Luard's own home. It was also pointed out that Chief Constable Henry Warde, who was leading the investigation into the murder, was also a close friend of General Luard.

Daniel Kettel and Anna Wickham claimed they heard three shots at around 3.15. Dr Mansfield, who carried out the post mortem examination, explained how the victim died: "Caroline Luard had been hit on the back of the head. The blow had been sufficient to knock her to the ground, where she had vomited. She had then been shot behind the right ear. That shot failed to kill her, so a second shot was fired into the left cheek."

Luard admitted that he owned three revolvers. However, he claimed that he could not remember where he kept his ammunition.

In their report on the inquest the Daily Chronicle argued that the theft of Mrs Luard's rings had been an attempt to cover the true motive behind her murder. The People newspaper claimed that the "police believe it was a deliberately planned crime... not the inspiration of the moment." The report suggested that the killer's name was known to the police.

Two woodcutters came forward to say that they had heard two shots at the time of the Mrs Luard's murder. They also said that just before the shots they heard a shrill squeal. This contradicted the account given by Daniel Kettel and Anna Wickham.

The day before Mrs Luard's funeral the pocket of her dress was found by a housemaid at Ightham Knoll. This pocket had been reported as missing during the first inquest. Rumours now began to circulate that Charles Luard had murdered his wife. Over the next few days he received several letters accusing him of the crime.

A second inquest was held at the George & Dragon Inn in Ightham. General Luard was questioned again. The coroner asked Luard if he was aware of "any incident in the lives of the deceased and yourself, which in your opinion would cause any person to entertain any feelings of revenge or jealously towards either of you?" Luard replied that he did not.

Mrs Mary Stewart told the coroner that she had arrived at Ightham Knollat 4.20 on the day of the murder. General Luard arrived five minutes later. He apologized for Mrs Luard not being home and he sat down and had a cup of tea with his guest. Stewart added: "We had tea and then he looked at his watch and suggested that he should go and meet her. I said I would go with him, as I wished to speak with Mrs Luard." They walked together before parting at 5.15.

Harriet Huish, the parlourmaid at Ightham Knoll, claimed that Mary Stewart arrived at 4.15 and not 4.20. She also said that General Luard arrived at 4.30 and not 4.25. Another servant, Jane Pugmore, confirmed that Mr and Mrs Luard were "on the best of terms" during the six years she had worked for the family.

London gunsmith Edwin Churchill stated that after looking at the two bullets he had concluded that they had come from a .320 revolver, which had been fired when the gun was no more than a few inches away from the victim's head.

Superintendent Albert Taylor was asked about the pocket of Mrs Luard's dress. He told the coroner that the pocket had been cut from the dress. A juror asked why the murderer would have done this. Taylor replied that he was sure the murderer had taken whatever money was in the pocket, then dropped it on the veranda before running away. This was supported by General Luard's testimony at the first inquest when he said: "I made an examination of her dress and found that her pocket was cut open and lying exposed on the veranda."

Taylor claimed he had taken possession of Mrs Luard's clothes after the post mortem, which had taken place on the day after the murder. He was asked if there was "any possibility of the pocket being in the dress at that time?" Taylor replied that "there can be no doubt that it was". He did not explain why Taylor told the first inquest that the pocket had gone missing. In fact, it had later been found in some bed sheets in Ightham Knoll by Jane Pugmore.

The Kent Messenger reported that it was expected that the coroner would announce a verdict of murder by person or persons unknown. However, Chief Constable Henry Warde asked for a second adjournment as he expected to find who was responsible for this crime during the next few days.

Rumours continued to circulate about the case. According to some stories, Mrs Luard had been shot by her lover - according to others, she was shot by the General because she had a lover. Another rumour suggested the General shot Mrs Luard because he had a lover.

Following the second inquest General Luard received dozens of letters accusing him of the crime. This included several letters with a local postmark. His close friend, Bertram Winnifrith, described these letters as "vile effusions".

Many years later, the author, Monty Parkin, interviewed several people who lived near Ightham Knoll. One woman, Rose Miles, claimed that it was common knowledge that the General's frequent excursions to the golf club were a front for an affair he was having with a woman in the village. However, others like Bertram Winnifrith, argued that it was a ridiculous idea that General Luard was capable of murdering his wife.

A fortnight after his wife's murder, General Luard announced he was leaving the district and advertised the remaining eight years of the lease on Ightham Knoll. He also arranged for the contents of the house to be auctioned off.

On 16th September, 1908, General Luard went to stay with Colonel Charles Warde MP, the brother of the Chief Constable. After dinner Mrs Warde retired early and left the two men talking.

The following morning General Luard did not come down for breakfast. One of the housemaids said she had seen the General come downstairs and leave the house by the garden door. Soon afterwards two policemen arrived with news that a body believed to be that of General Luard had been found on a local railway line.

At the inquest Frederick Bridges, the driver of the 9.00 Maidstone to Paddock Wood train, described how General Luard suddenly jumped out in front of his train. In a letter he left to Charles Warde he said: "I thought my strength was strong... In another letter to his brother Luard claimed that "it is all the horrid letters (destroyed) and insinuations that have been made" that resulted in his decision to commit suicide.

The Maidstone & Kentish Journal condemned the letter-writers with the words: "two murders have been committed in Kent this month. Mrs Luard was killed with a pistol; General Luard was killed with a pen".

On 12th May, 1909, David Woodruff was arrested for having a revolver at Bromley Union Workhouse. He was accused of pointing this weapon at the workhouse labour master. He was found guilty and sentenced to four months' hard labour.

On the morning Woodruff was due to be released from Maidstone Prison he was arrested and charged with the murder of Caroline Luard. Woodruff was taken before the Sevenoaks Magistrates and Superintendent Albert Taylor claimed that Chief Constable Henry Warde had acquired evidence that Woodruff was guilty of the killing of Caroline Luard. However, he refused to disclose this evidence. As a result, the magistrates released Woodruff. It was later discovered that Woodruff was in prison on the day of the murder. One of the magistrates involved in the case openly criticised Warde and expressed the opinion that his actions ought to be the subject of a full enquiry.

Stories began to circulate that Henry Warde was convinced that his friend, General Luard, was guilty of the murder of his wife and that the arrest of David Woodruff was part of a cover-up. However, this plan had failed because of Woodruff's alibi.

The murder of Caroline Luard is still unsolved.

Primary Sources

(1) Diane Janes, Edwardian Murder (2007)

Both Wickham and Harding concurred that the General's grief was terrible to behold. He was groaning and crying and when they finally reached the veranda, he threw himself on to his knees beside his wife, seized her hand and cried out, `She's dead, she's dead. Maggie, Maggie.

The alleged use of this name is somewhat confusing. Nowhere apart from the various newspaper accounts of this interview with Harding is there any reference to the victim's being called 'Maggie'. Maggie is not generally used as an abbreviation for either of Mrs Luard's names, which were Caroline Mary. Indeed, most sources claim that Mrs Luard was known to her family and friends as Daisy, and this was borne out by wreaths addressed to `Daisy Luard' at her funeral. It is possible that the General did use the name 'Maggie', but it seems more likely that Harding misheard him, or else that the reporters misheard Harding.

Harding described the scene which confronted them in some detail: explaining that the body was lying face downwards, with a glove to one side and an umbrella to the other, while the lady's hat lay a short distance away. Harding considered that from the position of the body Mrs Luard must have been walking across the veranda when her killer struck. He speculated that this person had hidden in an angle of the building, then sprung out on Mrs Luard. There was no sign of a struggle, he said, and no footprints in the immediate area, where the ground was hard or moss-covered.

(2) Major-General Charles Luard, letter to the Maidstone and Kentish Journal (8th September, 1908)

I should be very much obliged if you will permit me, through your columns, to acknowledge the very large number of telegrams, letters, and cards which I have recently received, expressing such deep sympathy for me.

The public at large has been deeply stirred by this awful crime and I may have some right to ask if the time has not arrived for clearing away from our roads, our lanes, and our woods, the many thousands of unemployed people, many of them in a desperate state from want, who may give way to temptation and commit the worst of sins.

(3) Major-General Charles Luard, letter to the Maidstone and Kentish Journal (18th September, 1908)

I am sorry to have returned your kindness and hospitality and long friendship in this way, but I am satisfied it is best to join her in the second life at once, as I can be of no further use to anyone in this world, of which I am tired and in which I do not want to live any longer.

I thought my strength was strong enough to bear up against the horrible accusations and terrible letters in reference to that awful crime, which has robbed me of all my happiness, and so it was for a long time. The kindness and sympathy of so many friends has kept me going on somehow. Now in the last day or two something seems to have snapped: the strength has left me and I care for nothing except to join her again.

So goodbye, dear friend.

PS. I shall be somewhere on the line of the railway. Please send the enclosed telegrams to Elmhirst my son; my brother-in-law and my maid.

(4) Diane Janes, Edwardian Murder (2007)

There can be little doubt that many local people suspected that the General had killed his wife. There was a widespread belief that the police net had been closing in on him and the General was tipped off that his arrest was imminent. Rather than face the disgrace of trial, arrest and the hangman's noose, the General was assumed to have `fallen on his sword'. According to one rumour, this course had been suggested to the General by a police sergeant, chosen for the delicate task because General Luard had helped him get into the police force in the first place, his father having previously worked as the Luards' gardener. This story had supposedly come from the mother of the police sergeant himself: though why a personal friend of the Chief Constable would need to have the situation spelt out by a lowly sergeant is not at all obvious - nor is there evidence that any serving police sergeant in 1908 was descended from any of the Luards' various gardeners..

In the absence of any other motive, it was suggested that the General had a lover. No candidate was named for the role and no evidence has ever been provided to link his name romantically with anyone other than Mrs Luard herself. This may have been a case of chicken and egg. The General was assumed to have killed his wife and therefore he must have had a motive and the most likely motive was that he must have had a lover.

Perhaps because the General was approaching 70, a more popular theory ran that the slightly younger Mrs Luard had a lover. In this set-piece melodrama, the summerhouse became the scene of their trysts - the fact that it was locked and there was not so much as a bench available on which the lovers could canoodle notwithstanding. One name was bandied about in connection with Mrs Luard - that of Dr Cecil Bosanquet - but it seems to have been linked to hers only long after she was dead.

Dr William Cecil Bosanquet was the bachelor son of Admiral George Bosanquet, whose house, Bitchet Wood, was a little south of Stone Street.4 The Bosanquets moved in the same social circles as the Luards, and had there been anything in this story, the Casa might have provided a useful meeting place because it was roughly half way between Ightham Knoll and Bitchet Wood.

This version of the tale has the General shooting Mrs Luard because of her affair with young Bosanquet. There is a huge problem with this theory in that by 1908 Dr Bosanquet had long ceased to live at his father's house in Kent. He ran a medical practice from Upper Wimpole Street in London, was a senior physician and medical tutor at Charing Cross Hospital, an assistant physician at Brompton Consumption Hospital, the author of numerous medical works and editor of others. Aside from the difficulties of being based 25 miles away, it is hard to see when Dr Bosanquet would have found the time to engage in an affair.

His father Admiral Bosanquet is scarcely a more likely candidate. He was 73 years old at the time of Caroline Luard's murder and would only live another five years. Arguing even more strongly against the General's entertaining the least hostility towards any member of the Bosanquet family is the fact that the Admiral was the 'dear friend' with whom Charles Luard had promised to spend two days before leaving Ightham for good - something probably not known by those who originated this rumour.

(5) C. H. Norman, memorandum sent to the Royal Commission on Capital Punishment (27th November 1950)

This subject has interested me for many years, particularly since the trial of Rex v. Dickman at the Newcastle Summer Assizes in July 1910, who was tried for the murder of a man named Nesbit [sic] in a train. Dickman was executed for what was an atrocious crime on 10 August 1910, his appeal at the Court of Criminal Appeal being dismissed on 22 July 1910. The case has always troubled me and converted me into an opponent of capital punishment. I attended the trial as the acting official shorthand writer under the Criminal Appeal Act. I took a different view to the jury; I thought the case was not conclusively made out against the accused. Singularly enough, in view of the nature of the crime, five of the jurymen signed the petition for reprieve, which could only be based upon the notion that the evidence was not sufficient against the accused.

It may be asked, why raise the question now? I am doing so partly because of Viscount Templewood's evidence, when he was reported as saying there was a possibility of innocent men being executed: partly because of the evidence of Viscount Buckmaster before the Barr Committee on Capital Punishment; but mainly because of the remarkable and disturbing matters concerning the Dickman case which have come to my knowledge over the intervening years, which I will now relate.

The Dickman case is the subject of a book by Sir S. Rowan Hamilton, which was published in 1914, based on the transcripts of the shorthand notes of the trial and certain other material. I did not read this book till August 1939, when owing to certain passages in the book, I wrote a letter to Sir S. Rowan-Hamilton, who had been Chief Justice of Bermuda, who replied as follows in a letter dated 26 October 1939:

The Cottage

Craijavak

Co. Down

Sir,

Your interesting letter of 24 August only reached me to-day. Of course, I was not present at the incident you referred to in the Judge's Chambers, but (Charles) Lowenthal (junior Crown counsel at Dickman's trial) was a fierce prosecutor. All the same Dickman was justly [convicted?], and it may interest you to know that he was with little doubt the murderer of Mrs Luard [who was shot dead at Ightham, near Sevenoaks, Kent, on 24 August 1908], for he had forged a cheque she had sent him in response to an advertisement in The Times (I believe) asking for help; she discovered it and wrote to him and met him outside the General's and her house and her body was found there. He was absent from Newcastle those exact days. Tindal Atkinson knew of this, but not being absolutely certain, refused to cross-examine Dickman on it. I have seen replicas of cheques. They were shown me by the Public Prosecutor. He was, I believe, mixed up in that case, but I have forgotten the details.

Yours truly

S. Rowan-Hamilton, Kt.

In 1938 there was published a book entitled Great Unsolved Crimes, by various authors. In that book there is an article by exSuperintendent Percy Savage (who was in charge of the investigations), entitled 'The Fish Ponds Wood Mystery', which deals with the murder of Mrs Luard, wife of Major-General Luard, who committed suicide shortly afterwards by putting himself on the railway line. In that article, the following passage appears: "It remains an unsolved mystery. All our work was in vain. The murderer was never caught, as not a scrap of evidence was forthcoming on which we could justify an arrest, and, to this day, I frankly admit I have no idea who the criminal was.' This book first came to my notice in February 1949, whereupon I wrote to Sir Rowan-Hamilton, reminding him of the previous letters, and asking for his observations on this statement of the officer who had conducted the inquiries into the Luard case. On 22 February 1949, I received the following reply from Sir S. Rowan-Hamilton:

Lisieux

Sandycove Road

Dunloaghaire

Co. Dublin

Dear Sir,

Thank you for your letter. Superintendent Savage was certainly not at Counsel's conference and so doubtless knew nothing of what passed between them. I am keeping your note as you are interested in the case and will send you later a note on the Luard case.

Yours truly

S. Rowan-Hamilton, Kt.

I replied, pointing out what a disturbing case of facts was revealed, as it was within my knowledge that Lord Coleridge, who tried Dickman, Lord Alverstone, Mr Justice A.T. Lawrence and Mr Justice Phillimore, who constituted the Court of Criminal Appeal, were friends of Major-General and Mrs Luard. (Lord Alverstone made a public statement denouncing in strong language the conduct of certain people who had written anonymous letters to Major-General Luard hinting that he had murdered his wife.) I did not receive any reply to this letter, nor the promised note on the Luard case.

Mr Winston Churchill, who was the Home Secretary who rejected all representations on behalf of Dickman, was also a friend of Major-General Luard.

So one has the astonishing state of things disclosed that Dickman was tried for the murder of Nesbit [sic] by judges who already had formed the view that he was guilty of the murder of the wife of a friend of theirs. If Superintendent Savage is to be believed, this was an entirely mistaken view.

I was surprised at the time of the trial at the venom which was displayed towards the prisoner by those in charge of the case. When I was called into Lord Coleridge's room to read my note before the verdict was given, on the point of the non-calling of Mrs Dickman as a witness, I was amazed to find in the judge's room Mr Lowenthal, Junior Counsel for the Crown, the police officers in charge of the case, and the solicitor for the prosecution. When I mentioned this in a subsequent interview with Lord Alverstone, he said I must not refer to the matter in view of my official position.

I did my best at the time within the limits possible. I went to Mr Burns, the only Cabinet Minister I knew well, and told him my views on the case and the incident in the judge's room; which I also told Mr Gardiner, the editor of The Daily News, who said he could not refer to that, though he permitted me to write in his room a last-day appeal for a reprieve, which appeared in The Daily News. Mr John Burns told me afterwards that he had conveyed my representations to Mr Churchill, but without avail.