Anti-Aircraft Weapons

Saturday 7th September, 1940, was a warm day with an almost cloudless sky. But soon after four in the afternoon the sky darkened as 300 German bombers and 600 escorting fighters arrived over London. It was the first day of the Blitz. The docks were the principal target, but many bombs fell on the residential areas around them resulting in 448 Londoners were killed and another 1,600 were seriously injured. (1)

The main criticism made by civilians after the first day of the Blitz was a lack of response from the British armed forces. Violet Regan, the wife of a member of the Heavy Rescue Squad in Millwall, reported: "We had depended on anti-aircraft guns... and apart from a solitary salvo loosed at the beginning of the raids, no gun had been shot in our defence... we felt like sitting ducks and no mistake." (2)

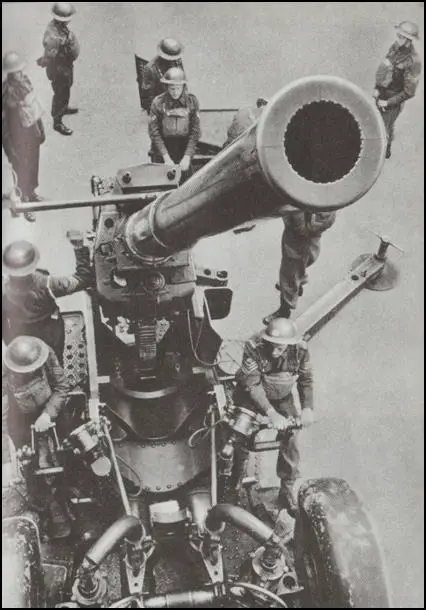

There were seven anti-aircraft (or ack-ack after the noise the guns made) divisions, but there was a grave shortage of weapons. Only half the heavy and a third of the light guns that had been considered essential before the war were in place. Most of these guns had been deployed to guard airfields during the Battle of Britain and so on 7th September, London was being defended by only 264 anti-aircraft guns. (3) The men often lacked the skills needed to operate these anti-aircraft guns. One report suggested that most training consisted of "so-called silent practice inside a drill hall." (4)

General Frederick Pile, commander-in-chief of the Anti-Aircraft Command, realised that "something must be done immediately" and "within twenty-four hours... reinforcements from all over the country were on their way to London and within forty-eight hours the number of guns had been doubled". Pile instructed "that every gun was to fire every possible round... every unseen target must be engaged without waiting to identify the aircraft as hostile". It was only on 10th September, the fourth night of the Blitz, men, many of whom had only just finished training, were ready to protect London. They were firing blind and "few bursts can have got anywhere near the target" since the tactic was to throw a enormous barrage of time-fused shells in front of a bomber formation and just hope that some of the planes would fly into it. (5)

It was pointed out: "It isn't easy to shoot down a plane with an anti-aircraft gun...In stead of sitting still, the target is moving at anything up to 300 m.p.h. with the ability to alter course left or right, up or down. If the target is flying high it may take 20 or 30 seconds for the shell to reach it, and the gun must be laid a corresponding distance ahead. Moreover the range must be determined so that the fuse can be set, and above all, this must be done continuously so that the gun is always laid in the right direction. When you are ready to fire, the plane, though its engines sound immediately overhead, is actually two miles away. And to hit it with a shell at that great height the gunners may have to aim at a point two miles farther still. Then, if the raider does not alter course or height, as it naturally does when under fire, the climbing shell and the bomber will meet. In other words the raider, which is heard overhead at the Crystal Palace, is in fact at that moment over Dulwich; and the shell which is fired at the Crystal Palace must go to Parliament Square to hit it." (6)

It was estimated that it took a lot of shells to bring down a German aircraft. However, coming as it did after three nights of the Luftwaffe having an almost uninterrupted passage to their targets, the non-stop barrage, seems to have forced the bombers to fly higher and even some to turn back. General Pile admitted that the anti-aircraft guns were not effective but it was important as "it bucked people up tremendously" and those Londoners sheltering from the raid could feel some confidence that there was, at last, some semblance of a battle. (7)

During September, 1940, AA batteries fired 260,000 rounds of heavy ammunition. It is estimated that it brought down only one aircraft for every 30,000 shells fired. This dropped to 11,000 in October and by January 1941 the experience gained by the operators, had reduced this figure to 4,000. Another reason was the establishment of a chain of radar warning stations. Once these had been integrated with operational control rooms to plot the movements of bombers and fighters and linked to radio direction of fighter squadrons, Britain had an effective defence system. (8)

As the commander-in-chief of the Anti-Aircraft Command pointed out: "Anti-aircraft guns take a little time to become effective after they have been moved to new positions. Telephone lines have to be laid, gun positions levelled, the warning system co-ordinated and so on." (9) Although official claims that 45 per cent of raiders were forced to turn back by anti-aircraft fire was not true and was merely government propaganda. German aircraft were forced to fly "higher as a result of the barrage, but since this made it more likely that the bombs would miss docks or railway stations and hit civilian homes instead, the advantage to the average citizen was not immediately noticeable." (10)

It has been claimed that on some occasions the barrage above London was so intense that as many civilians were killed and injured by shrapnel and unexploded shells as by enemy action. A survey was carried out after one raid and it was discovered that six people were killed by shell splinters; four wounded by a shell in Enfield; a sailor severely injured by a shell splinter in Gipsy Hill; two civilians killed by another shell elsewhere; one man killed and two injured by a shell which hit a wall in Battersea; and two more killed in Tooting." (11)

As Stuart Hylton, the author of Reporting the Blitz (2012) has pointed out: "By 1942 there were more women than men operating the anti-aircraft defences. But women were still not considered suitable for combat roles. So while they could operate the range finders and predictors that aimed the guns towards the target, firing the gun was strictly a man's job. More to the point, the women got different medals and a third less pay then the men, despite bearing an equal share of the dangers and discomforts." (12)

Primary Sources

(1) Basil Collier, The Defence of the United Kingdom (1957)

The intricate and enormous problems of night shooting were unknown to them, and impossible to explain. Londoners wanted to hear the guns shoot back; they wanted to feel that even if aircraft were not being brought down, at least the pilots were being made uncomfortable. It was abundantly apparent that every effort must be made to defend the Londoner more effectively, and to uphold his morale in so doing... Anti-aircraft guns take a little time to become effective after they have been moved to new positions. Telephone lines have to be laid, gun positions levelled, the warning system co-ordinated and so on.

(2) Stuart Hylton, Reporting the Blitz (2012)

By 1942 there were more women than men operating the anti-aircraft defences. But women were still not considered suitable for combat roles. So while they could operate the range finders and predictors that aimed the guns towards the target, firing the gun was strictly a man's job. More to the point, the women got different medals and a third less pay then the men, despite bearing an equal share of the dangers and discomforts.