Dorothy Hunt

Dorothy Wetzel was born in Ohio on 1st April, 1920. She became an employee for the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) after the Second World War and was stationed in Shanghai, China, where she met her future husband, E. Howard Hunt.

After the war Dorothy worked for the CIA in Paris. She was liaison between the American Embassy and the Economic Cooperation Administration (a CIA front). The couple returned to the United States and settled in Maryland. Her husband spent much of his time involved in covert operations in Mexico, Nicaragua, Guatemala, and Cuba.

On 3rd July, 1972, Frank Sturgis, Virgilio Gonzalez, Eugenio Martinez, Bernard L. Barker and James W. McCord were arrested while removing electronic devices from the Democratic Party campaign offices in an apartment block called Watergate. The phone number of E. Howard Hunt was found in address books of two of the burglars. Reporters were able to link the break-in to the White House. Bob Woodward, a reporter working for the Washington Post was told by a friend who was employed by the government, that senior aides of President Richard Nixon, had paid the burglars to obtain information about its political opponents.

E. Howard Hunt threatened to reveal details of who paid him to organize the Watergate break-in. Dorothy Hunt took part in the negotiations with Charles Colson. According to investigator Sherman Skolnick, Hunt also had information on the assassination of John F. Kennedy. He argued that if "Nixon didn't pay heavy to suppress the documents they had showing he was implicated in the planning and carrying out, by the FBI and the CIA, of the political murder of President Kennedy"

James W. McCord claimed that Dorothy told him that at a meeting with her husband's attorney, William O. Buttmann, she revealed that Hunt had information that would "blow the White House out of the water".

In October, 1972, Dorothy Hunt attempted to speak to Charles Colson. He refused to talk to her but later admitted to the New York Times that she was "upset at the interruption of payments from Nixon's associates to Watergate defendants."

On 15th November, Colson met with Richard Nixon, H. R. Haldeman and John Ehrlichman at Camp David to discuss Howard Hunt's blackmail threat. John N. Mitchell was also getting worried by Dorothy Hunt's threats and he asked John Dean to use a secret White House fund to "get the Hunt situation settled down". Eventually it was arranged for Frederick LaRue to give Hunt about $250,000 to buy his silence.

However, on 8th December, 1972, Dorothy Hunt had a meeting with Michelle Clark, a journalist working for CBS. According to Sherman Skolnick, Clark was working on a story on the Watergate case: "Ms Clark had lots of insight into the bugging and cover-up through her boyfriend, a CIA operative." Also with Hunt and Clark was Chicago Congressman George Collins.

Dorothy Hunt, Michelle Clark and George Collins took the Flight 533 from Washington to Chicago. The aircraft hit the branches of trees close to Midway Airport: "It then hit the roofs of a number of neighborhood bungalows before plowing into the home of Mrs. Veronica Kuculich at 3722 70th Place, demolishing the home and killing her and a daughter, Theresa. The plane burst into flames killing a total of 45 persons, 43 of them on the plane, including the pilot and first and second officers. Eighteen passengers survived." Hunt, Clark and Collins were all killed in the accident.

Just before Dorothy Hunt boarded the aircraft she purchased $250,000 in flight insurance payable to E. Howard Hunt. In his book Undercover (1974) Hunt claims he was unaware that his wife planned to do this. In the book he also tried to explain what his wife was doing with $10,000 in her purse. According to Hunt it was money to be invested with Hal Carlstead in "two already-built Holiday Inns in the Chicago area".

The following month E. Howard Hunt pleaded guilty to burglary and wiretapping and eventually served 33 months in prison. Hunt kept his silence although another member of the Watergate team, James W. McCord, wrote a letter to Judge John J. Sirica claiming that the defendants had pleaded guilty under pressure (from John Dean and John N. Mitchell) and that perjury had been committed.

The airplane crash was blamed on equipment malfunctions. Carl Oglesby (The Yankee and Cowboy War) has pointed out that the day after the crash, White House aide Egil Krogh was appointed Undersecretary of Transportation, supervising the National Transportation Safety Board and the Federal Aviation Association - the two agencies charged with investigating the airline crash. A week later, Nixon's deputy assistant Alexander P. Butterfield was made the new head of the FAA.

Several writers, including Robert J. Groden, Peter Dale Scott, Alan J. Weberman, Sherman Skolnick and Carl Oglesby, have suggested that Dorothy Hunt was murdered. In 1974, Charles Colson, Howard Hunt's boss at the White House, told Time Magazine: "I think they killed Dorothy Hunt." (7/8/1974)

Barboura Morris Freed also raised several issues in her article, Flight 553: The Watergate Murder? Freed claimed that Attorney General John N. Mitchell was under investigation for corruptly helping the El Paso Natural Gas Company against its main competitor, the Northern Natural Gas Company. Mitchell's decision to drop anti-trust charges was worth an estimated $300 million to El Paso. Ralph Blodgett and James W. Kreuger, two attorneys working for Northern Natural Gas Company in the investigation of Mitchell, were both killed in the crash. .

Freed also claimed that just hours after the crash an anonymous call was made to the WBBM Chicago (CBS) talk show. The caller described himself as a radio ham who had monitored ground control's communications with 553, and he reported an exchange concerning gross control tower error or sabotage. CBS, the employer of Michelle Clark, kept this information from the authorities investigating the accident. One FBI agent went straight to Midway's control tower and confiscated the tape containing information concerning the crash. The FBI did this before the NTSB could act - a unique and illegal intervention.

Freed also pointed out that FBI agents were at the scene of the crash before the Fire Department, which received a call within one minute of the crash. The FBI later claimed that 12 agents reached the scene of the crash. Later it was revealed that there were over 50 agents searching through the wreckage.

(It was completely irregular for the FBI to get involved in investigating a crash until invited in by the National Transportation Safety Board. The FBI director justified this action because it considered the accident to have been the result of sabotage. That raises two issues: (i) How were they able to get to the crash scene so quickly? (ii) Why did they believe Flight 553 had been a case of possible sabotage? Freed does not answer these questions. However, it could be argued that it is possible to answer both questions with the same answer. The FBI had been told that Flight 553 was going to crash as it landed in Chicago.

Primary Sources

(1) E. Howard Hunt, Undercover (1974)

Dorothy told me that upon her return from Europe she had called Douglas Caddy on several occasions and received what she considered were unsatisfactory responses. She had been unable to reach Liddy. Confronted with this situation, and not knowing where I was or what faced me, she went to CREP headquarters and demanded to see the general counsel, an attorney named Paul O'Brien. Dorothy went on to say that O'Brien had blanched when she told him of my involvement with Gordon Liddy, and he said he would look into the circumstances at once. Mr. Rivers' call, she theorized, was in response to her enlightenment of Paul O'Brien.

Presently Bittman reported that during a conversation with CREP's attorneys - in connection with the DNC civil suits against us - he had been assured that Mr. Rivers was an appropriate person for him or Dorothy to deal with.

On the following day Dorothy received a phone call from a man identifying himself as Mr. Rivers. He said he did not want to hold any discussions with her over our home telephone line, but if she would be at a particular phone booth in Potomac Village, he would call her half an hour later.

When my wife returned, she told me that Mr. Rivers had instructed her to obtain from the arrested men, Liddy and myself an estimate of monthly living costs and attorneys' fees. This she was to do by the following day, when she was to be at a different phone booth to receive a call from Mr. Rivers. Accordingly, she telephoned James McCord, then Bernard Barker, asking the latter for a combined estimate covering all four Miami men. These figures she delivered to Mr. Rivers during their subsequent telephone contact, after which he said, "Well, let's multiply that by five to cut down on the number of deliveries."

Dorothy asked him why he was using a multiple of five - aware that five months represented the interval to the national Presidential election - and was told by Rivers that five was a convenient figure for him to multiply by.

Within a day or so Dorothy was instructed by Rivers to drive to National Airport, go to a particular wall telephone in the American Airlines section and reach under it for a locker key taped to the underside. This she did and opened a nearby locker to find in it a blue plastic airlines bag, which she brought home.

Later she told me that the contents had been considerably less than the figure agreed upon by Mr. Rivers. In fact, she told me, the monthly budget had been multiplied by three rather than five, so on that basis she set about distributing the funds. Liddy, she told me, was to receive his support funds and attorneys' fees directly through a separate channel.

The transaction represented verification of what Liddy had told me during his dramatic appearance at Jackson's home in Beverly Hills - that everyone would be taken care of, Company-style - and so I faced the future with renewed confidence that all obligations would be kept...

I was at Bittman's law offices on the evening of October 20 when Bittman answered the telephone and told me a messenger was on his way - theoretically with money. In due course a package was delivered to the then vacant reception desk, and after Bittman handed it to me, I opened it and turned over its contents to him and Austin Mittler. The precise sum I have no way of recalling, but I remember that it was far less than what was owed my attorney. And of course there was nothing in the package for family support for myself or for Liddy, McCord or the Miami men.

Dorothy now expressed to me her great dissatisfaction at the role she had been asked to undertake by Mr. Rivers. It was he who had solicited budget figures from her; they had been agreed to, yet the payments had never been fully met. Now Dorothy was dealing with "a friend of Mr. Rivers," and she felt that with the election won, the White House would be less inclined to live up to its assurances. Moreover, she had the lingering feeling that because she was a woman, her representations were given less weight than those of a man - myself, for example. For these reasons she suggested that I call Colson and attempt to explain the situation to him. On instructions of Mr. Rivers, she had given specific financial assurances to the Miami defendants, but the money had been only partially forthcoming. And their lawyer was making disquieting sounds.

So I phoned Colson's office on November 13, speaking with his secretary, Holly Holm. After checking with her boss, she told me I could call Colson the following day from a phone booth - not my home phone. The hour was, I believe, twelve o'clock, and after salutations I congratulated Colson on the electoral victory and suggested that with the election out of the way, people in the White House ought to be able to get together and concentrate on the fate of us seven defendants. I informed him that despite all previous assurances - some of which had been met - financial support was greatly in arrears, particularly payment of legal fees for the defendants. I believed the seven of us had behaved manfully and remarked that this was "a two-way street." I told him that, in the language of clandestine service, money was the cheapest commodity there was. By that I meant that men - the Watergate defendants - were not expendable, but money was. And money was badly needed for legal defense and the support of our families.

(2) Taped conversation between Richard Nixon and John Dean (28th February, 1973)

John Dean: Kalmbach raised some cash.

Richard Nixon: They put that under the cover of a Cuban committee, I suppose?

John Dean: Well, they had a Cuban committee and they... some of it was given to Hunt's lawyer, who in turn passed it out. You know, when Hunt's wife was flying to Chicago with $10,000 she was actually, I understand after the fact now, was going to pass that money to one of the Cubans - to meet him in Chicago and pass it to, somebody there.... You've got then, an awful lot of the principals involved who know. Some people's wives know. Mrs. Hunt was the savviest woman in the world. She had the whole picture together.

Richard Nixon: Did she?

John Dean: Yes. Apparently, she was the pillar of strength in that family before the death.

Richard Nixon: Great sadness. As a matter of fact there was discussion with somebody about Hunt's problem on account of his wife and I said, of course commutation could be considered on the basis of his wife's death, and that is the only conversation I ever had in that light.

(3) (3)Anthony Ulasewicz, The President's Private Eye (1990)

At first, she (Dorothy Hunt) told me that she had lost her job over the Watergate scandal including her medical benefits. She said somebody had to take care of those. She started calculating everybody's needs and came up with a minimum figure of $3,000 a month, but as she didn't want to worry about a monthly delivery from the post man, it was better, she said, to get a big chunk up front to relieve the pressure on everybody. "So let's start with $10,000 or $15,000 apiece to get this thing off the ground," she said. She wanted the advance to cover five months of living expenses. She said Barker, Sturgis, Gonzales, and Martinez needed at least $14,000 apiece and that Barker needed another $10,000 for bail, $10,000 more under the table, and $3,000 for "other expenses." Twenty-five grand apiece were needed for Sturgis, Gonzales, and Martinez's attorneys. I told Mrs. Hunt to slow down. Now she was talking about $400,000 or maybe $450,000. That wasn't even close to the amount Dean had told Kalmbach to raise when they met in Lafayette Park.

When I told Mrs. Hunt that I had no room to negotiate and that it was pointless to present me with a shopping list of who needed what, she said people were starting to get desperate. They felt they were being abandoned. She added a new name when she told me that one of those who needed money was a guy named Liddy. He was involved in the break-in along with the "writer" but hadn't yet been charged with anything. That was news. Hunt's name had been found in an address book kept by one of the Watergate burglars. So had the name Colson. Now Mrs. Hunt was adding another name to the stew. I was a stranger to Mrs. Hunt, and yet she was telling me something that proved Hunt's connection to Colson in the White House. With Liddy in the picture the ring of involvement was widening, and I was learning more than I wanted to know. That was the first time I heard the name Liddy. The way she spoke about him, however, made me feel that she was looking for a way to deal him out of the game as quickly as she could. Liddy had to get some of the money, but just one payment and that was it, she said. Others had to be covered, lots of others whom she said were more important than Liddy. Living expenses were high for all these other people. Money was needed over and under the table. (I doubted many people in Washington really knew the difference.) She said that her husband and the other defendants wouldn't have to go to jail for very long because meetings were going on about that and about pardons and immunity.

The pressure that was building behind the scenes for the payment of increasingly large sums of money to those connected directly and indirectly to the Watergate break-in was turning this "one-shot deal" into a multiheaded tapeworm. It had some appetite, and to feed it, I had to meet Kalmbach on four different occasions to pick up additional sums of money. The first installment was the $75,000 I took out of the Statler Hilton in a laundry bag. The next dump in my lap was at the Regency Hotel in New York where I walked out with $40,000. The third course of the burglars' meal, $28,900, was again given to me at the Statler Hilton in Washington. Kalmbach gave me the last amount off the menu as we sat in a car outside the Airporter Motel at the Orange County Airport in California. It consisted of $75,000 in cash.

I delivered a total of $154,000 to Dorothy Hunt in four separate installments: $40,000, $43,000, $18,000 and $53,000. She was never satisfied with the amount of money I gave her. She never believed that 1 didn't have (and didn't want) the power to determine the breadth of financial support she said was necessary to keep things afloat. Neither Kalmbach nor I knew whether she was delivering what those involved were supposed to receive. She kept telling me about Barker's problems down south; that he needed a lot of cash to keep the lid on things in Miami. Again, she talked about Liddy as if she was trying to give him the shaft. She told me she was worried that Liddy's wife might crack under the strain. Mrs. Liddy was a school teacher and was frightened that she might lose her job if it was discovered that her husband was involved. Dorothy Hunt seemed to want to help Liddy's wife and yet get rid of her at the same time.

(4) Peter Dale Scott, Deep Politics and the Death of JFK (1993)

Of the more than a dozen suspicious deaths in the case of Watergate... perhaps the most significant death was that of Dorothy Hunt in the crash of United Air Lines in December 1972. The crash was investigated for possible sabotage by both the FBI and a congressional committee, but sabotage was never proven. Nevertheless, some people assumed that Dorothy Hunt was murdered (along with the dozens of others in the plane). One of these was Howard Hunt, who dropped all further demands on the White House and agreed to plead guilty (to the Watergate burglary in January 1973).

(5) Alan J. Weberman, Coup D'Etat in America: The CIA and the Assassination of John F. Kennedy (1975)

After the plane carrying Hunt's wife Dorothy crashed under mysterious circumstances in December 1973, the chairman of the National Transportation Safety Board told the House Government Activities Subcommittee that he had sent a letter to the FBI which stated that over fifty agents came into the crash zone. The FBI denied everything until William Ruckleshaus became temporary Director, at which time they admitted that their agents were on the scene. The independent researcher Sherman Skolnick believes that Dorothy Hunt was carrying documents that linked Nixon to the Kennedy assassination. According to Skolnick these papers, which were being used to blackmail Nixon, were seized by the FBI. Skolnick's theory is corroborated by a conversation that allegedly took place between Charles Colson and Jack Caufield.

According to Caufield, Colson told him that there were many important papers the Administration needed in the Brookings Institution and that the FBI had recently adopted a policy of coming to the scene of any suspicious fires in Washington D.C. Caufield believed that Colson was subtly telling him to start a fire at Brookings and the FBI would then steal the desired documents.

Note at this point that one day after the plane crash, White House aide Egil Krogh was appointed Undersecretary of Transportation. This gave him direct control over the National Transportation Safety Board and the Federal Aviation Administration-the two agencies that would be in charge of investigating the crash. Soon Dwight Chapin, Nixon's Appointment Secretary, became a top executive at United Airlines. Dorothy Hunt was on a United carrier when she made her ill-fated journey.

(6) E. Howard Hunt, Undercover (1974)

In the morning available information was inconclusive. Few of the dead had been identified, and not all of the injured. At midday an attorney who was a partner of Hal's in the motelmanagement firm joined us to use his good offices with the Chicago police and coroner. I told him that Dorothy was travelling with $10,000 in cash for the investment and had perhaps $700 in her purse besides. He suggested I sketch some of the jewelry she was wearing, and I did: wedding ring, family signet ring, engagement ring and finally a large solitaire diamond that had been my mother's.

A party had been planned for Dorothy, and Phyllis telephoned the invited guests to cancel the affair. Since the day before I had eaten nothing and slept little; from time to time I began crying uncontrollably.

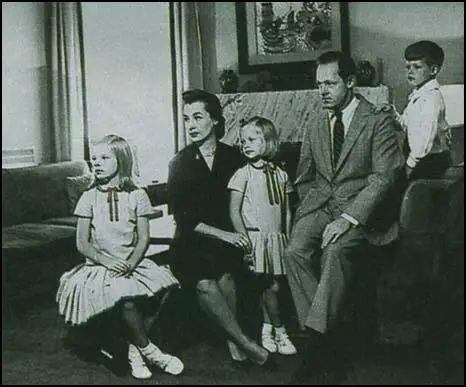

Kevan telephoned me from our home but I was unable to tell her whether her mother was alive or dead. I spoke with the other children, all in highly emotional states, which increased my own. The United Airlines passenger agent who had given us his card seemed to be unavailable and we could get no information from other United offices.

Toward midafternoon the attorney returned to the Carlstead house and suggested that we go to the Cook County morgue, taking the sketches I had made of Dorothy's jewelry.

It was a long ride through gathering dusk to the ugly and solitary old building, and when our party had identified itself, we sat down for a long wait. Finally a functionary returned with a plastic bag containing scorched jewelry. This he emptied onto a table and I stared at it unbelievingly. Everything I had sketched was there - except my mother's diamond solitaire. The wedding ring.

I picked it up and held it in my hand; ashes dropped from it, smudging my palm. The charm bracelet, half melted by the heat. Her signet ring had not been harmed.

The man said, "Can you identify these, Mr. Hunt?"

I nodded wordlessly. To another functionary he said, "That takes care of body eighteen," and gave me a form to sign.

(7) Letter from John Reed, chairman of the National Transportation Safety Board to FBI Director William Ruckelshaus (5th June, 1973)

As you may know, the National Transportation Safety Board is currently investigating the aircraft accident of the United Air Lines Boeing 737, at Midway Airport, Chicago, on December 8, 1972. Our investigative team assigned to this accident discovered on the day following the accident that several FBI agents had taken a number of non-typical actions relating to this accident within the first few hours following the accident.

Included were: for the first time in the memory of our staff, an FBI agent went to the control tower and listened to the tower tapes before our investigators had done so; and for the-first time to our knowledge, in connection with an aircraft accident, an FBI agent interviewed witnesses to the crash, including flight attendants on the aircraft prior to the NTSB interviews. As I am sure you can understand, these actions, particularly with respect to this flight on which Mrs. E. Howard Hunt was killed, have raised innumerable questions in the minds of those with legitimate interests in ascertaining the cause of this accident. Included among those who have asked questions, for example, is the Government Activities Subcommittee of the House Government Operations Committee. On the basis of informal discussions with the staff of the Committee, it is likely that questions as to what specific actions were taken by the FBI in connection with this aircraft accident, and why such actions were taken, will come up in a public oversight hearing at which the NTSB will appear and which is now scheduled for June 13, 1973.

In order to be fully responsive to the Committee, as well as to be fully informed ourselves about all aspects of this accident so as to assure the complete accuracy of our determination of the probable cause, we would appreciate, being advised of all details with respect to the FBI activities in connection with this accident. We would like to have, for example, the following information: the purpose of the FBI investigation, the reasons for the early response and unusual FBI actions in this case, the number of FBI personnel involved, all investigative actions taken by the agents and the times they took such actions (including the time the first FBI agents arrived on the scene), and copies of all reports and records made by the agents in connection with their investigations (we already have copies of 26 FBI interview reports; any other documents should be provided, therefore).

While we have initiated action at the staff level between our agency and yours to effect better liaison and avoid engaging in efforts which may be in conflict in the future, we have determined that some more formal arrangement in the nature of an interagency memorandum of agreement of understanding, for instance would seem appropriate. It would clearly delineate our respective statutory responsibilities and set forth procedures to eliminate any future conflicts. We would therefore appreciate it if you would designate, at your earliest convenience, an official with whom we may discuss this matter and with the authority to negotiate such a formal agreement with the Safety Board.

In the interim, however; we would like to receive, in advance of the scheduled June 13, 1973, public oversight hearing, the specific information concerning the actions of the FBI in connection with the Midway - accident and the reasons therefore, in order to enable us to be as fully responsive as possible to the House Subcommittee.

(8) Letter from FBI Director William Ruckelshaus to John Reed, chairman of the National Transportation Safety Board (11th June, 1973)

Your letter dated June 5, 1973, concerning the FBI's investigation into the crash of a United Air Lines Boeing 737 at Midway Airport, Chicago, Illinois, on December 8, 1972, has been received.

The FBI has primary investigative jurisdiction in connection with the Destruction of Aircraft or Motor Vehicles (DAMV) Statute, Title 18, Section 32, U.S. Code, which pertains to the willful damaging, destroying or disabling of any civil aircraft in interstate, overseas or foreign air commerce. In addition, Congress specifically designated the FBI to handle investigations under the Crime Aboard Aircraft (CAA) Statute, Title 49, Section 1472, US Code, pertaining, among other things, to aircraft piracy, interference with flight crew members and certain specified crimes aboard aircraft in flight, including assault, murder, manslaughter and attempts to Commit murder or manslaughter.

FBI investigation of the December 8, 1972 United Air Lines crash was instituted to determine if a violation of the DAMV or CAA Statutes had occurred and for no other reason. The fact that Mrs. E. Howard Hunt was aboard the plane was unknown to the FBI at the time our investigation was instituted.

It has been longstanding FBI policy to immediately proceed to the scene of an airplane crash for the purpose of developing any information indicating a possible Federal violation within the investigative jurisdiction of the FBI. In all such instances liaison is immediately, established with the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) personnel upon their arrival at the scene.

Approximately 50 FBI Agents responded to the crash scene, the first ones arriving within 45 minutes of the crash. FBI Agents did interview witnesses to the crash, including flight attendants. Special Agent (SA) Robert E. Hartz proceeded to the Midway Airport tower shortly after the crash to determine if tower personnel could shed any light as to the reason for the crash. On arriving at the tower, SA Hartz identified himself as an FBI Agent and explained the reason for his presence. He was invited by Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) personnel at the tower to listen to the recording made at the tower of the conversation between the tower and United Air Lines Flight 553. At no time did SA Hartz request to be allowed to listen to the tapes. After listening to the tapes, SA Hartz identified a sound as being that of the stall indicator on the aircraft. The FAA agreed that SA Hartz was right and immediately notified FAA Headquarters at Washington, D.C.

The FBI's investigation in this matter was terminated within 20 hours of the accident and on December 11, 1972, Mr. William L. Lamb, NTSB, was furnished with copies of the complete FBI investigation pertaining to this crash after it was determined there was apparently no violation of the DAM or CAA Statutes.

In order to avoid the possibility of any misunderstanding concerning our respective agencies' responsibilities and to insure continued effective liaison between the NTSB and the FBI, I have designated SA Richard F. Bates, Section Chief, Criminal Section, General Investigative Division, FBI Headquarters, Washington, DC, telephone number 324-2281, to represent the FBI concerning any matters of mutual interest.

(9) Carl Oglesby, The Yankee and Cowboy War (1976)

Based on the facts agreed upon by both sides, it is at least apparent from these letters (see above) that the FBI was all over Dorothy Hunt at the time of the crash, despite Ruckelshaus's, protest that Dorothy Hunt's presence on 553 was "unknown to the FBI at that time." There is no obvious way such a large response as fifty agents within the hour could have been generated from a standing start as of the moment of the crash itself. The closest FBI office is forty minutes from the crash site and there are never fifty agents available at once without warning. It is tradition that FBI agents do not gather in offices waiting for calls but stay in the field. When a really obvious intelligence agent, Hungarian Freedom Fighter Lazlo Hadek, died in a crash the next summer at Boston's Logan Airport, leaving a trail of secret NATO nuclear documents strewn down the center of the runway, the FBI was barely able to get a solitary agent to the scene on the same day as the wreck. That this same FBI could get fifty agents to the scene of the Chicago crash within an hour is to my mind an arresting piece of information. How could the FBI have done this if it had not had Dorothy Hunt's airplane, for whatever reason, under full company-scale surveillance before the crash ever happened? And why might the FBI have been doing that?

Note in this connection that it was specifically the airplane itself that was being followed; and not the person of Dorothy Hunt. That is, no FBI agent was aboard the plane. If the FBI was tailing Dorothy Hunt, why was she not being followed on the plane? Was it that her flight was too sudden? But it was delayed on the ground for fifteen minutes. Michelle Clark of CBS, who was on the same flight, knew she was going to be on it and may have been her companion in the first-class cabin. The Hunts took enough time at the airport to buy $250,000 worth of flight insurance.

Ruckelshaus does not meet Reed's main questions. He reads the book with a straight face as though Reed had asked him what were the statutory grounds of the FBI intervention instead of why, suddenly, this time and no other time, and so massively, and hence with such a semblance of advance contrivance, were these grounds taken up and acted upon. One understands that the FBI will always be able to - demonstrate a rudimentary legal basis for whatever it takes it its head to do. What we want to know is where these whims arid fancies bubble up from.

We wonder finally what in the world made the FBI think S53's crash might have been a case of "willful disabling of a Civil aircraft," or of "crimes aboard aircraft , in flight including assault, murder, and manslaughter"? Not that any of this necessarily happened or did not, but the FBI does not usually behave as if it might have. Does it? How does Ruckelshaus account for this, especially in view of his assertion that the FBI acted with no knowledge of Dorothy Hunt's presence? What was the chain-of-command activity and what were the reasons that had so many FBI agents waiting to move when that plane came down?

(10) Lalo J. Gastriani, Fair Play Magazine, The Strange Death of Dorothy Hunt (November, 1994)

It was at 2:29 PM on Friday, December 8, 1972, during the height of the Watergate scandal that United Airlines flight 553 crashed just outside of Chicago during a landing approach to Midway Airport. Initial reports indicated that the plane had some sort of engine trouble when it descended from the clouds. But the odd thing about this crash is what happened after the plane went down. Witnesses living in the working-class neighborhood in which the plane crashed said that moments after impact, a battalion of plainclothes operatives in unmarked cars parked on side streets pounced on the crash-site. These so-called 'FBI types' took control of the scene and immediately began sifting through the wreckage looking for something. At least one survivor recognized a "rescue worker"--clad in overalls sifting through wreckage - as an operative of the CIA.

One day after the crash, the Whitehouse head of Nixon's "plumber's" outfit - Egil Krogh, Jr. - was made undersecretary of transportation, a position that put him in a direct position to oversee the National Transportation Safety Board and the Federal Aviation Agency which are both authorized by law to investigate airline crashes. Krogh would later be convicted of complicity in the break-in of Daniel Ellsberg's Psychiatrist's office along with Hunt, Liddy and a small cast of CIA-trained and retained Cuban black-bag specialists.

About a month after Krogh's new assignment, Nixon's appointments secretary, Dwight Chapin, was made an executive in the Chicago office of United Airlines, where he threatened the media to steer clear of speculation about sabotage in the crash. On December 19th - eleven days after the crash - Nixon appointed ex-CIA officer, Alexander Butterfield, as head of the FAA. Students of Watergate will remember Butterfield as the Whitehouse official who supervised Nixon's secret taping system and who exposed the existence of the infamous tapes that ultimately would force Nixon to resign.

Ostensibly traveling with Mrs. Hunt on flight 553 was CBS news corespondent Michelle Clark who, rumor had it, had learned from her sources that the Hunts were about to spill the proverbial beans regarding the Nixon whitehouse and its involvement in the Watergate burglary; Clark also died in the crash.

A large sum of money (between $10,000 and $100,000) was found amid the wreckage in the possession of Mrs. Hunt. It was during this time that Dorothy Hunt was traveling around the country paying off operatives and witnesses in the Watergate operation with money her husband had extorted from Nixon via his counsel, John Dean. Hunt had threatened Nixon and Dean with exposing the nature of all the sordid deeds he had done.

Could it be that the fuel for Hunt's blackmail of the president had little to do with the so-called "third-rate burglary" of the Democratic headquarters? Could it have had more to do with the fate of John F. Kennedy and of Nixon's awareness of who was really behind the planning and deployment of his demise? In the Watergate tapes, Nixon displays a malignant paranoia to his chief-of-staff, H. R. Haldeman, concerning E. Howard Hunt and the Bay of Pigs operation...

After reading in the spring of 1991 James Hougan's amazing Watergate book, Secret Agenda, I began a Freedom of Information Act search on certain FBI documents related to the death of Dorothy Hunt. I was especially intrigued by the report by Hougan, that amongst the cash Mrs. Hunt had in her possession, was a $100 bill with the inscription, "Good Luck FS". I immediately suspected that FS could stand for Howard's Watergate co-conspirator and fellow CIA affiliate, Frank Sturgis, and began searching for other crash-material ascribed to Mrs. Hunt from the ill-fated flight.

In Secret Agenda, Hougan describes an engineer, Michael Stevens, proprietor of the Chicago-based Stevens Research Laboratories, as being visited in early May, 1972 by Watergate wireman James McCord who had come to place orders for ten highly-sophisticated eavesdropping devices - much more sophisticated units than the cheap, commercial-grade bugs supposedly found in the DNC the next month in June.

Stevens claims that Dorothy Hunt was traveling to see him in Chicago when her plane went down and that the $10,000 or more she possessed was intended for him as an installment for his silence. Stevens says he told the FBI that his own life had been threatened anonymously and that Hunt's death was a homicide.

(11) The Spotlight, is a nightly radio call-in talk forum on Radio Free America. On 14th February, 1994, host Tom Valentine interviewed independent investigator Sherman Skolnick.

Tom Valentine: The Watergate plane crash is the first investigation you and I worked on together.

Sherman Skolnick: This subject is one of the great forbidden subjects of this country. You are not supposed to talk publicly about airplanes that have been sabotaged. If sabotage is ever brought up, it’s always in some foreign country where a bomb blows up the airplane.

Tom Valentine: Then the loss of the United Airlines flight 553 was not just fog or pilot error or something like that.

Sherman Skolnick: In the history of aviation there have been a number of situations where there was actual sabotage - not necessarily a bomb - and that sabotage put the plane down and killed people for political reasons.

I started writing a book about airplane sabotage right after the plane crash. I called it “The Watergate Plane Crash.” The reason why was because on this one plane were 12 people connected with the Watergate affair.

The disaster happened exactly one month after Richard Nixon had been re-elected. The Watergate affair had started, but it was not widely known at the time.

Former CIA man (and Watergate burglar) E. Howard Hunt, part of the so-called White House Plumbers, was under arrest. It later came out that Hunt was threatening to blow the lid off the White House if Nixon didn’t take care of him. Hunt wanted $2 million.

What Hunt reportedly had was information tending to show that Nixon, who was in Dallas at the time John F. Kennedy was murdered, was complicit in the assassination. Hunt’s wife Dorothy was carrying around “hush” money to various witnesses in an effort to silence them about the Watergate affair.

She was on flight 553, and this time she was traveling under her own name. She was so concerned about the baggage (which contained $2 million worth of cashier’s checks and money orders, which some astute people could have traced back to the Nixon White House) that she bought an extra first class seat for her baggage (and the valuables therein).

The press later said there was only $10,000 in her possession, but that was false. We know about this because of records of the National Transportation Safety Board which had the manifest of the airplane.

(12) Chicago Public Library, Crash of United Airlines Flight 533 (1996)

"This was probably the most investigated airplane crash in history" said Deputy Cook County Coroner John Haigh when he announced the findings of the coroner's jury looking into the crash at Midway Airport. The findings coincided with those of the National Transportation Safety Board: pilot error.

Flight 533 left Washington DC for Omaha, Nebraska stopping in Chicago. Approaching Midway the pilot was instructed by the control tower to execute a "missed approach" pattern. The pilot applied full power to go around for another landing attempt. At 2:27 p.m., 1.5 miles from the airport, Flight 533 hit the branches of trees on the south side of 71st Street. It then hit the roofs of a number of neighborhood bungalows before plowing into the home of Mrs. Veronica Kuculich at 3722 70th Place, demolishing the home and killing her and a daughter, Theresa. The plane burst into flames killing a total of 45 persons, 43 of them on the plane, including the pilot and first and second officers. Eighteen passengers survived.

Among the passengers killed were U.S. Representative George Collins (7th), a former 24th Ward Alderman, and Mrs. Dorothy Hunt. Her husband, E. Howard Hunt, had been indicted on charges of conspiring to break into the Democratic National Committee Headquarters in the Watergate Hotel. Found in the debris was a purse belonging to Mrs. Hunt containing $10,585 in cash. There was immediate concern that the money might be linked to the financial dealings surrounding the Nixon "slush fund" to which defendants in the Watergate case had access and that the crash therefore might be linked to sabotage. In the end sabotage was ruled out, but the mystery surrounding the money and the deaths of such prominent, politically connected individuals insured a very thorough investigation.

The NTSB issued its report after recreating the last minutes of the flight based on the flight and voice recording instruments, interviews with survivors and eyewitnesses on the ground, and physical evidence. According to the report, when Midway's control tower directed the crew to abort the landing and try again, they became distracted and failed to prepare a proper landing. As they attempted to pull the jet from the landing descent, the crew forgot to deactivate the wing spoilers. The plane stalled. And then it crashed.

(13) Rodney Stich, Defrauding America (2001)

A United Boeing 737 crashed into a Chicago residential area (December 8, 1972) during an approach, killing everyone on board, including the wife of Watergate figure E. Howard Hunt. She was reportedly carrying money to silence Watergate witnesses, and carried papers implicating President Richard Nixon in the coverup. A Chicago public-interest group, know as the Citizens Committee believed that Justice Department personnel played a role in the crash of United flight 553, and that they wanted key individuals on flight 553 exterminated. Twelve of the people who boarded United Flight 553 had something in common relating to questionable Justice Department and Watergate activities.

There had been a gas pipeline lobbyist meeting as part of the American Bar Association in Washington, D.C., conducted by Roger Morea. Among the lobbyists attending were attorneys for the Northern Natural Gas Company of Omaha; attorneys for Kansas-Nebraska Natural Gas Company; and the president of the Federal Land Bank in Omaha. The Citizens Committee portrayed these people as a group determined to blow the lid off the Watergate case.

For many years Chicago resident Lawrence O'Connor boarded flight 553 like clockwork. He had no Watergate connections, but he had friends in the White House. On this particular Friday, O'Connor supposedly received a call from someone he knew in the White House, strongly advising him not to take flight 553. The caller advised him to go to a special meeting instead of taking that flight. Whether this was coincidental or to save his life is unknown to me, although the Citizens Committee considers it significant.

U.S. Attorney General John Mitchell, later indicted and sent to federal prison, and the Justice Department were putting pressure on Northern Natural Gas. The firm had subsidiaries that the federal government indicted on federal criminal charges in Omaha, Chicago, and Hammond, Indiana. (September 7, 1972.) Justice Department charges included bribery of local officials in Northwest Indiana and Illinois, to get clearance for installing the pipeline through their state.

Allegedly to blackmail the Justice Department and cause them to drop the charges, the Omaha firm uncovered documents showing that Mitchell, while attorney general in 1969, dropped antitrust charges against a competitor of Northern Natural Gas - El Paso Natural Gas Company. Just before the crash, Carl Kruger, an official with Northern Natural Gas Company, had been browbeating federal officials to drop the criminal charges.

The Citizens Committee alleged that dropping these charges saved the utility 300 million dollars. Simultaneously, Mitchell purchased through a law partner a stock interest in El Paso Natural Gas Company. Gas and oil interests, including El Paso, Gulf Resources, and others, contributed heavily to Nixon's spy fund supervised by Mitchell. The Citizens Committee reported that Kruger had previously been warned he would never live to reach Chicago. Kruger carried these revealing documents on United Flight 553, telling his wife that he had irreplaceable papers of a sensitive nature in his possession. For months after the crash Kruger's widow demanded that United Airlines turn his briefcase over to her.

CBS news reporter Michelle Clark travelled with Mrs. Hunt, doing an exclusive story on Watergate. Ms. Clark had already gained considerable insight into the bugging and coverup through her boyfriend, a CIA operative. Others knew of this exclusive interview, including the Justice Department.

(14) Sherman Skolnick, The Secret History of Airplane Sabotage (8th June, 2001) .

Upwards of twelve persons connected in one way or another with Watergate, boarded United Air Lines Flight 553 on the afternoon of December 8, 1972. They had something in common. That week there had been a gas pipeline lobbyists meeting as part of the American Bar Association meeting in Washngton, DC It was conducted by Roger Moreau. His secretary was Nancy Parker. Among those attending were Ralph Blodgett and James W. Krueger, both attorneys for the Northern Natural Gas Co., of Omaha, Nebraska. Associated with them were Lon Bayer, attorney for Kansas-Nebraska Natural Gas Co.; Wilbur Erickson, president, Federal Land Bank in Omaha. This was a belligerent group determined to blow the lid off the Watergate case. Reason Former US Attorney General, John Mitchell, and his friends running the Justice Department were putting the spear into Northern Natural Gas. Some officials of that firm and its subsidiaries were indicted on federal criminal charges, September 7, 1972, in Omaha, Chicago, and Hammond, Indiana. Charge bribery of local officials in Northwest Indiana to let the gas pipeline go through. To blackmail their way out of these charges, the Omaha firm had uncovered documents showing that Mitchell, while U.S. Attorney General in 1969, dropped anti-trust charges against a competitor of Northern Natural Gas - El Paso Gas Co. The dropping of the charges against El Paso was worth 300 million dollars. A spokesman for Mitchell belatedly claimed, in March, 1973, that Mitchell had "disqualified" himself in 1969, because Mitchell's law partner represented El Paso. The Justice Department under Mitchell, dropped the charges. Period. About the same time, Mitchell, through a law partner as nominee, got a stock interest in El Paso. Gas and oil interests, such as El Paso, Gulf Resources, and others contributed heavily to Nixon's spy fund, supervised by Mitchell.

Pipeline official Krueger was carrying the Mitchell-El Paso documents on the plane. He had told his wife that he had in his possession irreplaceable papers of a sensitive nature. For months after the crash, his widow demanded, to no avail, that United Air Lines turn over to her his briefcase. It later came out in the pipeline trial in Hammond, that Blodgett had been browbeating federal officials, to drop the criminal charges just prior to the crash. (Our investigation uncovered that most of the local officials, to be government witnesses against the pipeline, were murdered just prior to trial. In all, some five Northwest Indiana officials.)

Dorothy Hunt, Watergate pay-off woman, who offered executive clemency directly on behalf of Nixon to some of the Watergate defendants, was seeking to leave the US with over 2 million dollars in cash and negotiables that she had gotten from CREEP, Committee to Re-Elect the President. (She was so concerned about these valuables, she purchased a separate first class seat next to her on the plane for this luggage.) She and her husband, E. Howard Hunt, the Watergate conspirator, were a "C.I.A. couple", two agents "married" and living together. Early in December, 1972, both were threatening to blow the lid off the White House if (a) he wasn't freed of the criminal charges; (b) Nixon didn't pay heavy to suppress the documents they had showing he was implicated in the planning and carrying out, by the FBI and the CIA, of the political murder of President Kennedy; and (c) Dorothy and Howard Hunt didn't both get several million dollars. Some of these details are in the Memo of Watergate double-agent, James McCord, a CIA official in charge of the Agency's physical security; details before the Senator Ervin Committee. Hunt claimed, according to McCord, to have the data necessary to impeach Nixon. McCord said matters were coming to a head early in December, 1972. Mrs. Hunt was unhappy with her job of going all over the country to bribe defendants and witnesses in the bugging case. She wanted out.

Mrs. Hunt was on the way to arrange to take her money out of the country, possibly Costa Rica, to link up with international swindler Robert Vesco who was there at the time; through Harold C. Carlstead, whose wife was Mrs. Hunt's cousin. Carlstead reportedly did accounting and tax work for mobster-owned businesses in the Chicago area. He operated two Holiday Inn motels in Chicago's south suburbs - at 174th and Torrence, Lansing, Illinois and at 171st and Halsted, Harvey, Illinois. Carlstead's motel on Torrence was reportedly a favorite hang out for gangsters and dope traffickers such as apparently "Cool" Freddie Smith, Grover Barnes, and the late Chicago mobster Sam DeStefano (who aided the American CIA in bloody tricks and was snuffed out to silence him), to name a few. Mrs. Hunt had (a) Ten Thousand Dollars in untraceable cash; (b) Forty Thousand Dollars in so-called "Barker" bills, traceable to Watergate spy Bernard Barker; and (c) upwards of Two Million Dollars in American Express money orders, travelers checks, and postal money orders. (As shown by testimony before the National Transportation Safety Board, re-opened Watergate plane crash hearings, June 13-14, 1973. Hearings reopened as a result of my lawsuit claiming sabotage covered up by the N.T.S.B.) Carlstead issued a fake "cover" story that had (only) Ten Thousand Dollars with Mrs. Hunt. A story swallowed up by the Establishment Press.

Mrs. Hunt got on Flight 553 with Michele Clark, CBS Network newswoman, going to do an exclusive story on Watergate. Mrs. Hunt, Mitchell, Nixon - the story could have destroyed Nixon at the time. Ms Clark had lots of insight into the bugging and cover-up through her boyfriend, a CIA operative. In the summer of 1972, prior to any major revelations of Watergate, Ms Clark tried to pick the brains of Chicago Congressman George Collins, regarding the bugging of the Democratic headquarters. Ms Clark was sitting with Collins on the plane.

After the crash, Michele Clark's employer, CBS Network News, ordered and demanded that the body be cremated by the southside Chicago mortician handling the matter - possibly to cover up foul play. Later, the mortician was murdered in his business establishment, an unsolved crime. (We interviewed close confidants of her family who informed us of the details how CBS applied tremendous pressure and offered large sums for silence on the crash details and having her body cremated contrary to her family's wishes.)

Also on the plane were four or more people who knew about a labor union that had given a large "donation" to CREEP to head-off an criminal indictment of a Chicago labor union hoodlum (at the time of the book, 1973, actively investigated by us).

For many years, like clockwork, one Chicagoan went to Washington, D.C. on Monday and came back Friday afternoon on Flight 553 or its equivalent Lawrence T. O'Connor, Apt. 5-C, 999 North Lake Shore Drive, Chicago, Illinois. On Friday, December 8, 1972, he received a call from someone he knows in the White House, telling him not to take Flight 553 but to go instead to a special meeting.

My long-time friend, political activist Dick Gregory, informed me that there had been strenuous efforts to steer him that same afternoon onto United Air Lines Flight 553. Luckily, he had changed his mind.

Also getting on Flight 553 was a reputed "hit-man", pursuing Mrs. Hunt and others, and going under the "cover" of being a top Narcotics official with DALE (Drug Abuse Law Enforcement). He used the name Harold R. Metcalf. He is an unusual "narc"; he worked directly for Nixon. Metcalf told the pilot he was packing a gun, and so Metcalf was assigned seat B-17, near the stewardesses' jump seat and also near the food galley and the rear door of the plane. After the crash, he walked out of the cracked open fuselage of the pancaked plane wearing a jumpsuit. A former Military Intelligence investigator, who used his credentials to get into the crash site, identified the person posing as "Harold Metcalf" as an overseas CIA parachute spy. Metcalf evidently supervised certain foul play, possibly cyanide, directed at certain passengers, but he didn't know of the over all sabotage plan. One of our staff investigators confronted Metcalf about a week after the crash: (a) Metcalf, supposedly a government narcotics bigshot, knows nothings about dope. (b) in response to our question, "Did you know the plane was sabotaged?", he blurted out half a sentence, "It was not supposed to....", turning purple, he then left the room. Evidently, he was a double cut-out, an espionage term for an operative to be himself eliminated by someone else. His survival was an oversight.