PART

3 : THE GROWTH OF PHOTOGRAPHIC STUDIOS IN BRIGHTON ( 1854-1861

)

Photographic

Portrait Studios

In the ten years between November 1841 and November 1851, William

Constable, aided by a few assistants, was the only photographic

artist operating a portrait studio in Brighton.

When W.J.Taylor's Original Directory of Brighton was compiled

for the year 1854, ten photographic studios were listed :

Edward COLLIER 58, King's Road

Charles and John COMBES 62, St James's Street

William CONSTABLE 57, Marine Parade

Lewis DIXEY 21, King's Road

Robert FARMER 59 & 114 North Street

GREY & HALL 13, St James's Street

Jesse HARRIS 213, Western Road

HENNAH & KENT 108, King's Road

William LANE 213, Western Road

Madame Agnes RUGE 180 Western Road

All the photographers listed in Taylor's 1854 directory appeared

under the heading 'ARTISTS - Daguerreotype', yet we know Hennah

& Kent specialised in talbotypes, Lewis Dixey stocked

photographic apparatus for the calotype and collodion processes,

Farmer produced calotypes using a waxed paper process and Grey

& Hall employed "three distinct processes" - talbotype

and collodion as well as daguerreotype.

To the 10 studios listed by Taylor's Directory in 1854 we can

add the names of the artists Edward Fox junior and George

Ruff, both of whom were using a camera to make views of Brighton

in the early 1850s.

William Constable, who for 10 years had enjoyed a monopoly

in the production of photographic portraits, was now faced with

up to a dozen competitors. In the summer of 1854, Constable closed

his original studio at 57 Marine Parade and removed his photographic

business to the Old Custom House at 58 King's Road, where he joined

forces with the daguerreotype artist Edward Collier. The

Partnership of Constable & Collier continued for about

3 years. By 1858, William Constable was listed as the sole proprietor

of the Original Photographic Institution at 58 Kings' Road.

In June 1855, the Brighton and Sussex Photographic Society

was formed. The Photographic Society held monthly meetings and

was open to amateurs and professionals. An amateur, the Reverend

Watson acted as chairman, while the post of Honorary Secretary

was held by Constable's business partner and professional daguerreotype

artist Edward Collier. By September 1855, the Photographic Society

boasted 40 members.

James Henderson, a well known London daguerreotype artist,

arrived in Brighton in the summer of 1855, but by September he

had moved on to Cornwall, to establish a portrait studio in Launceston.

Henderson may have been deterred by the number of photographers

already active in Brighton. Folthorp's Brighton Directory, which

had been corrected to September 1856, adds three more photographic

studios not listed in Taylor's earlier directory. George Ruff,

who had been taking daguerreotype since around 1850, finally presented

himself as a professional photograher in 1856. Also listed in

1856 was the firm of Merrick & Co and James

Waggett, who had previously operated as a manufacturer

and tuner of pianofortes at 193 Western Road. Photographic artists

were listed in the section on Professions and Trades in Brighton

directories, but these listings do not provide a complete picture.

William G Smith is described as a photographic artist in

the 1856 street directory, but his name does not appear as a photographer

in the 'professions and trades' directory. William Lane,

an important name in the early history of photography in Brighton,

is not listed in Folthorp's Directory of 1856, yet newspaper advertisements

from this time show that William Lane was employing two other

operators, Mr Davis and Mr Warner, and in addition to his main

studio at 213 Western Road, Lane had a branch studio in Shoreham.

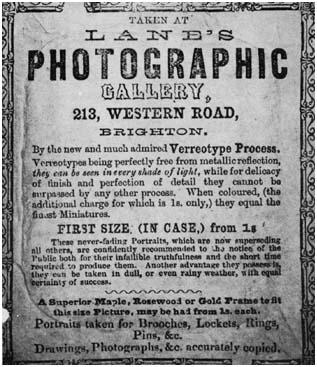

Portrait

of a Boy (c1855). "Verreotype" portrait taken at Lane's

Photographic Gallery, 213 Western Road. William Lane called his

collodion positives "verreotypes". In America they were

known as "ambrotypes".

The

Decline of the Daguerreotype

By the time Folthorp's Directory of 1856 was published, the daguerreotype

was on its way out. All the photographers listed in the Professional

and Trades section of Folthorp's Directory appear under the heading

Photographic and Talbotype Galleries. 'Farmer's Daguerreotype

Rooms' had become 'Farmer's Photographic Institution' and William

Lane had abandoned the daguerreotype for his Verreotype process.

In an advertisement dated 3 January 1856, William Lane

promoted his new and improved Verreotype Process, by detailing

the advantages the new process had over the daguerreotype. Verreotypes,

Lane proclaimed, were perfectly free from metallic reflection

and could be seen "in every shade of light." Verreotype

portraits took only a short time to produce and could be "taken

in dull, or even rainy weather . . . when it would be quite impossible

to operate with the Daguerreotype method." Lane states confidently

in his advertisement that "these never fading Portraits .

. . are now superseding Daguerreotypes."

Stereoscopic

Photographs

In

1838, the English scientist and inventor Sir Charles Wheatstone

(1802-1875) had described the phenomena of binocular vision and

designed apparatus which fused two separate drawings into a single

three dimensional image. To describe this viewing instrument,

Wheatstone coined the term "Stereoscope" (from the Greek

words 'stereos' meaning "solid" and 'skopein' meaning

"to look at") With the advent of photography, Wheatstone's

reflecting stereoscope, which utilised mirrors, could be used

to view a pair of almost identical photographs and give the illusion

of depth.

Sir David Brewster (1781-1868), a Scottish physicist, designed

a stereoscope that employed two lenses which mimicked binocular

vision. Jules Duboscq (1817-1886) a Parisian optician constructed

an improved stereoscope based on Brewster's design, which merged

two photographs of the same subject to form a three-dimensional

picture.

At the Great Exhibition of 1851, Queen Victoria was particularly

impressed by Duboscq's stereoscope and the accompanying stereoscopic

photographs. Queen Victoria's interest in the stereoscope

signalled the start of a popular demand for stereoscope viewers

and stereoscopic photographs. In 1856, Brewster reported over

half a million of his stereoscopes had been sold.

A few stereoscopic talbotypes had been made for Wheatstone soon

after the introduction of photography in 1839. In the early 1850s,

however, most of the early stereoscopic photographs were daguerreotypes.

Duboscq had displayed a set of his own stereoscopic daguerreotypes

at the Great Exhibition of 1851. In 1853, Antoine Claudet

patented a folding stereoscope which could view stereo daguerreotypes.

A couple of years after the Great Exhibition of 1851 stereoscopic

photography arrived in Brighton. In 1853, Thomas Rowley,

Optician to the Sussex and Brighton Eye Infirmary, was advertising

his "superior selection of stereoscopes with Daguerreotype

plates, Collodion and Photographic Pictures" which could

be hired from his premises at 12 St James Street. In November

1853, Robert Farmer of the Daguerreotype Rooms, 59 North

Street was offering to provide a "stereoscopic Portrait,

with Stereoscope, 10s 6d, complete." Lewis Dixey,

Optician and Dealer in Photographic Apparatus, announced in 1854

that he could supply "Stereoscopes & Stereoscopic subjects

in Calotype, Daguerreotype & Collodion or Glass." George

Ruff of 45 Queens Road, Brighton specialised in stereoscopic

portraits in colour.

Stereo Cards

The reflective surface of a silvered copper plate was not ideal

for stereoscopic effects and the process did not lend itself to

the manufacture of large quantities of stereo pictures. With the

advent of the collodion glass negative and photographic prints

on albumenized paper in the mid 1850s, the mass production of

stereo cards became possible.

The London Stereoscopic Company, founded in 1854 by George

Swan Nottage, was a firm that specialized in the mass production

of stereoscopic photographs. Nottage's company responded to the

enormous demand for stereoscopes and stereo cards. By 1856, The

London Stereoscopic Company had sold over 500,000 stereoscopes

and had 10,000 titles in its trade list of stereo cards. Two years

later, in 1858, The London Stereoscopic Company claimed to have

100,000 stereo cards in stock [ George Swan Nottage (1823-1885)

had connections with Brighton. He owned property in the town and

was a regular visitor to Brighton. At the time of the 1861 Census

George Swan Nottage was residing at 15 Marine Parade, Brighton

and when he died in April 1885, he had just returned from an Easter

holiday at the seaside town.]

In 1857, The Brighton Stereoscopic Company based at 121

St James Street, near the Old Steine was selling stereoscopes

from half a crown (2s 6d/121/2 p) and stereoscopic views were

on sale at a shilling (1s/10 p) each.

The fashion for collecting and viewing stereoscopic photographs

reached its peak in the early 1860s. In 1862 alone, The London

Stereoscopic Company had sold a milliion stereoscopic views.

A wide variety of stereoscopic images could be purchased - views

of faraway places, (Japan, The Andes) scenes of everyday life,

anecdotal pictures, humorous tableaux scenes, 'still life' arrangements

and pictures of life in town and country.In 1858, Samuel Fry,

a photographic artist based at 79 Kings Road, Brighton,even produced

a "Stereograph of the Moon"

Some of the stereoscopic views sold in Brighton were of purely

local interest.

In March 1863, William Cornish junior of 109 Kings Road,

Brighton was advertising a set of six stereoscopic photographs

of a decorated railway shed. The 531 ft. long railway shed was

used to house 7,000 school children who had gathered for a meal

to celebrate the marriage of Edward, Prince of Wales and Princess

Alexandra of Denmark. Stereoscopic views of the decorated railway

shed could be purchased singly for one shilling (10 pence) or

the customer could buy a complete set for 6 shillings

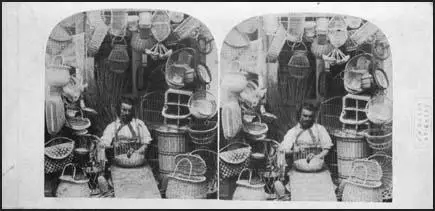

William Mason junior, the son of W.H.Mason, printseller

and proprietor of the Repository of Arts in Brighton's Kings Road,

photographed scenes featuring local craftspeople, such as basketmakers,

and issued them as stereographic cards.

Stereocard

of a Brighton Basketmaker by W H Mason junior (c1862)

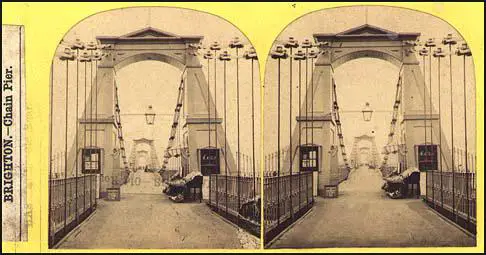

More typically, the Brighton artist Edward Fox, who specialised

in landscape photography, advertised "local views as stereoscopic

slides." Familiar landmarks in Brighton, such as the Royal

Chain Pier and the Royal Pavilion became popular subjects for

stereo cards.Some of Edward Fox junior's stereoscopic slides featured

particularly dramatic scenes. Fox's titles included " The

Chain Pier During a Gale " and " Chain Pier by Moonlight".

Stereocard of the Chain

Pier, Brighton c1870

Albumen in Photography

Albumen is a clear,organic material found in its purest form in

the white of an egg. Smooth, transparent and sticky, albumen was

seen as a suitable binder in photography. In 1847, the French

army officer and chemist Abel Niepce de Saint-Victor (1805-1870),coated

glass plates with egg-white mixed with potassium iodide and then

sensitized the dried plates in a bath of silver nitrate. The albumen-coated

glass plates made fine, photographic negatives, but exposure times

ranged from five to fifteen minutes and so were only really suitable

for photographing landscapes or buildings. Albumen glass negatives

were soon superseded by Fred Scott Archer's collodion glass negatives.

The Albumen Print

In 1850, L. D. Blanquart-Evrard (1802-1872), a French photographer,

introduced albumenized paper for photographic prints. Albumen

from the white of an egg was mixed with sodium chloride. Sheets

of thin paper were coated with the albumen mixture and then sensitized

with silver nitrate. A collodion glass negative could produce

finely detailed photographs on albumenized paper. By the 1860s,

most photographers were using collodion glass negatives and albumenized

paper in the production of photographic prints.

Blanquart-Evrard exhibited his albumen prints at the Great Exhibition

of 1851, announcing that his new process made it "possible

to produce two or three hundred prints from the same negative

the same day." The albumen print became an essential

component for the mass production of photographic images and played

an important part in meeting the public demand for stereographic

cards and carte de visite portraits in the 1860s.

Outdoor Photography

When Joseph Nicephore Niepce created the earliest surviving

photograph in 1826, the materials he used were so insensitive

it took 8 hours of sunlight for the image to be fixed on the pewter

plate he had prepared. Niepce's heliograph ('sun drawing') was

a view of his courtyard, taken from a top floor window. In 1839,

when photography was first introduced to the world, camera exposure

times ranged from five to fifteen minutes and so the only suitable

subjects were buildings, landscapes and arrangements of still

life. The majority of the pictures made by L.J.M.Daguerre himself

are of buildings and views in Paris.

Artists and amateurs may have been content to use the new invention

to produce a pleasing landscape or record an interesting building,

but astute businessmen knew that financial reward and commercial

success would lie in portrait photography. Every effort had been

made to reduce camera exposure times so that the daguerreotype

process could be used to make portraits. By the early 1840s technical

advances in photography meant that a sitter would only have to

hold a pose for a number of seconds rather than a number of minutes.

When Richard Beard, the patentee of the daguerreotype process

in England and Wales, sold licences authorising the setting up

of 'Photographic Institutions' in provincial towns, the purchasers

were mainly interested in using the invention to "take likenesses."

Outdoor Photography in Brighton Before

1854

The journalist who in November 1841 welcomed the opening of William

Constable's 'Photographic Institution' on Marine Parade in the

pages of the Brighton Guardian, recognised that the main purpose

of photography was to secure "a correct likeness without

the tedium of sitting for hours to an artist."

William Constable made his living from taking "likenesses",

charging his customers one guinea for "a portrait in a plain

morocco case", but it is known that he occasionally took

his camera on to the streets of Brighton. In the 1840s, Constable

took views of fashionable houses in Kemp Town, and two daguerreotypes

of houses in Lewes Crescent ended up in the photograph collection

of Richard Dykes Alexander.

In the early 1850s, local artists Edward Fox junior and

George Ruff senior were taking photographs of buildings

in Brighton. Ruff made a daguerreotype of St Nicholas Church around

1850 and Edward Fox, who declared in later advertisements that

he had "given his whole attention to Out-Door Photography

since 1851", produced pictures of shop fronts, churches and

other public buildings in Brighton and the surrounding area. In

1853, Robert Farmer, proprietor of the 'Daguerreotype Rooms'

in North Street, Brighton was exhibiting his calotype views of

the Royal Pavilion and the Railway Terminus and daguerreotype

views of Brighton's oldest church.

The

West Battery, Kings Road (c1850)

Outdoor Photography in Brighton 1855-1862

With the advent of the collodion process, more and more photographers

in Brighton were taking their cameras out on the street to record

life in the town.

Old buildings and structures scheduled for demolition were a favourite

subject for photographers, who were anxious to record them for

posterity. For example, a battery of eight guns was established

in Brighton's West Cliff in the 1790s to protect the town from

French attacks by sea. In 1857, it was decided to remove the West

Battery so that Brighton's main thoroughfare, the King's Road,

could be widened. Work commenced in January 1858 and from this

date a series of photographs recorded the progress of the dismantling

of the battery and the breaking up of the artillery ground.

In 1862, a row of old houses and shops that ran from 41 to 43

North Street, was scheduled for demolition. A set of oval shaped

photographs recorded the shop fronts and the rear ends of the

buildings that were to be demolished. It is not clear exactly

why these photographs were commissioned, but they allow us to

glimpse not only a vanished parade of Victorian shops, but also

a few bystanders, some of whom would not have been able to afford

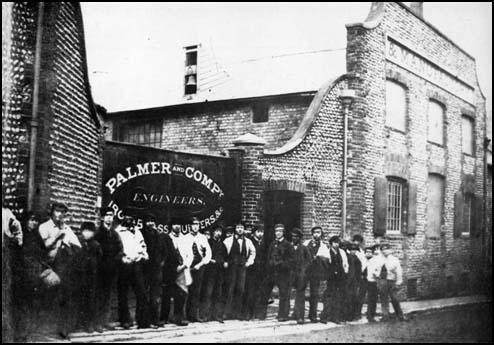

the services of a photographer. Another gorup of workers whose

wages probably would not stretch to pay for a sitting at the professional

portrait studio, are captured on a photograph showing the entrance

ot the premises of Palmer and Company, Engineers and Iron Founders.

Workers

employed by Palmer & Co.Engineers stand

outside the company's premises in North Road. (c1865)