Spartacus Blog

Was Winston Churchill a supporter or an opponent of Fascism?

To many people this might appear to be a daft question. They will all remember that Winston Churchill, as prime minister, led the fight against those well known fascists, Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler during the Second World War. Most people will be aware of his attacks on Neville Chamberlain and his policy of appeasement that is reflected in his wise words: "An appeaser is one who feeds a crocodile - hoping it will eat him last.” However, he did not actually say that. What he said was "Each one hopes that if he feeds the crocodile enough, the crocodile will eat him last." The date of the quotation is also important, it was made during the war on 20th January, 1940. (1)

The truth is that for most of the 1930s Churchill was an advocate of appeasement. As late as July, 1938, he was involved in his own negotiations with representatives of Hitler's government in Nazi Germany. During a meeting with Albert Forster, the Nazi Gauleiter of Danzig, he asked Churchill whether German discriminatory legislation against the Jews would prevent an understanding with Britain. Churchill replied that he thought "it was a hindrance and an irritation, but probably not a complete obstacle to a working agreement." (2)

The historical record shows that Churchill was a great admirer of fascism. This information can not only be found in private letters and diary entries, but in his speeches and articles he produced in the 1920s and 1930s. Most of his biographers, except Boris Johnson, in his terrible book, The Churchill Factor (2014), have accepted this embarrassing fact, but they have tended to underplay its importance. But as the author of the highly sympathetic biography, Churchill: A Study in Greatness (2001) has pointed out, Churchill was "not an anti-Fascist until very late in the day". (3)

The Origins of Fascism

On the outbreak of the First World War the leadership of Italian Socialist Party opposed Italian involvement in the conflict. Benito Mussolini, one of its members, who disagreed with this strategy, left the party and formed the Fasci Rivoluzionari d'Azione Internazionalista. Members of the organization called themselves Fascisti (Fascists). The movement was very small and and angry socialists made it difficult for them to hold public meetings. These early hostilities between the Fascists and socialists shaped Mussolini's ideas of the nature of Fascism in its support of political violence. (4)

In 1917, Sir Samuel Hoare, the Conservative Party MP for Chelsea, and a member of the right-wing Anti-Socialist Union, was also MI5's man in Rome. He arranged for Mussolini to be paid £100 week to help ensure Italy continued to fight alongside the allies in the war by publishing propaganda in his newspaper. He was also willing to send in his men, to "persuade'' peace protesters to stay at home. According to the historian, Peter Martland, who discovered details of the deal struck with the future dictator, said: "Britain's least reliable ally in the war at the time was Italy after revolutionary Russia's pullout from the conflict. Mussolini was paid £100 a week from the autumn of 1917 for at least a year to keep up the pro-war campaigning - equivalent to about £6,000 a week today... The last thing Britain wanted were pro-peace strikes bringing the factories in Milan to a halt. It was a lot of money to pay a man who was a journalist at the time, but compared to the £4m Britain was spending on the war every day, it was petty cash." (5)

During this period Mussolini developed his theory of fascism and the corporate state. Mussolini wrote that fascism is the opposite of Marxism, which explains history simply as the conflict of interests. The Fascist denies the economic conception of history and the idea of class war. Mussolini argued for the Corporate State where the ruling party acts as a mediator between the workers, capitalists and other prominent state interests by institutionally incorporating them into the ruling mechanism. (6)

In May 1921 General Election the Italian Socialist Party won 24.7 per cent of the vote. The liberal, left of centre, Italian People's Party was second with 20.4 per cent and a right-wing nationalist coalition was third with 19.1 per cent. The Communist Party on Italy won over 4.6 per cent. Luigi Facta, of the IPP became the prime minister. Mussolini now attempted to unite right-wing forces by establishing the National Fascist Party in November, 1921. This was instrumental in directing and popularizing support for Mussolini's ideology. One of Mussolini's close confidants, Dino Grandi, formed armed squads of war veterans called blackshirts with the goal of restoring order to the streets of Italy. This resulted in armed clashes with communists, socialists, and anarchists at parades and demonstrations. (7)

On 28th October 1922, about 30,000 Fascist blackshirts, led by Benito Mussolini, gathered in Rome to demand the resignation of Luigi Facta and the appointment of a new Fascist government. King Victor Emmanuel III refused the government request to declare martial law, which led to Facta's resignation. The King then handed over power to Mussolini who enjoyed wide support in the military and among the industrial and agrarian elites, while the King and the conservative establishment were afraid of a possible communist revolution. (8)

Giacomo Matteotti, the leader of the Unitary Socialist Party, was murdered by fascists on 10th June 1924. The death of Matteotti sparked widespread criticism of Fascism. However, Mussolini defended the violence used against socialists and communists. He claimed that Fascism was the "superb passion of the best youth of Italy" and that "all the violence" was his responsibility, because he had created the climate of violence. He admitted that the murderers were Fascists of "high station" and "I assume, I alone, the political, moral, historical responsibility for everything that has happened." (9)

A law passed on 24th December 1925, transformed Mussolini's government into a legal dictatorship. In the same year, an electoral law abolished parliamentary elections. The Italian Socialist Party and the Italian Communist Party were banned and on 8th November, 1926, Mussolini drew up a list of politicians to be arrested. This included Antonio Gramsci, who was accused of provoking class hatred and civil war. Gramsci was found guilty and he was later to die in prison. (10)

Winston Churchill was a great admirer of Benito Mussolini and welcomed both his anti-socialism and his authoritarian way of organising and disciplining the Italians. He visited the country in January 1927 and wrote to his wife, Clementine Churchill, about his first impressions of Mussolini's Italy: "This country gives the impression of discipline, order, goodwill, smiling faces. A happy strict school... The Fascists have been saluting in their impressive manner all over the place." (11)

Churchill met Mussolini and gave a very positive account of him at a press conference held in Rome. Churchill claimed he had been "charmed" by his "gentle and simple bearing" and praised the way "he thought of nothing but the lasting good... of the Italian people." He added that it was "quite absurd to suggest that the Italian Government does not stand upon a popular basis or that it is not upheld by the active and practical assent of the great masses." Finally, he addressed the suppression of left-wing political parties: "If I had been an Italian, I am sure that I should have been whole-heartedly with you from the start to the finish in your triumphant struggle against the bestial appetites and passions of Leninism." (12)

Winston Churchill and Democracy

Churchill had been a long time opponent of democracy. At Harrow School he studied the arguments against democracy put forward by Plato and Aristotle. As Aristotle pointed out: "When quarrels and complaints arise, it is when people who are equal have not got equal shares." One solution to this is to introduce democracy but Aristotle warned about the dangers of this system: "Democracy is when the indigent (poor), and not the men of property, are the rulers." This of course is unpopular with the ruling class. Aristotle believed the best system is when you have magnanimous rulers. "The magnanimous man, since he deserves most, must be good, in the highest degree; for the better man always deserves more, and the best man most. Therefore the truly magnanimous man must be good. And greatness in every virtue would seem to be characteristic of the magnanimous man." Aristotle then goes on to suggest that monarchy is the best form of government, and aristocracy the next best. Monarchs and aristocrats can be "magnanimous", but ordinary citizens cannot. (13)

Of course, by the time Churchill became involved in politics, Britain had accepted a limited democracy with most men having the vote. In the first volume of his autobiography, Churchill wrote: "All experience goes to show that once the vote has been given to everyone and what is called full democracy has been achieved, the whole political system is very speedily broken up and swept away." (14) Churchill told his son that democracy might destroy past achievements and that future historians would probably record "that within a generation of the poor silly people all getting the votes they clamoured for they squandered the treasure which five centuries of wisdom and victory had amassed." (15)

Winston Churchill disagreed with women having the vote. As a young man he argued: "I shall unswervingly oppose this ridiculous movement (to give women the vote)... Once you give votes to the vast numbers of women who form the majority of the community, all power passes to their hands." His wife, Clementine Churchill, was a supporter of votes for women and after marriage he did become more sympathetic but was not convinced that it should happen. When a reference was made at a dinner party to the action of certain suffragettes in chaining themselves to railings and swearing to stay there until they got the vote, Churchill's reply was: "I might as well chain myself to St Thomas's Hospital and say I would not move till I have had a baby." However, at the time he was member of the Liberal Party government that had promised women the vote and could not express these opinions in public. (16)

Churchill, as Home Secretary played a leading role in preventing women achieving the vote. Under pressure from the Women's Social and Political Union in 1911, the Liberal government introduced the Conciliation Bill that was designed to conciliate the suffragist movement by giving a limited number of women the vote, according to their property holdings and marital status. However, Churchill argued in the House of Commons against the measure on the grounds that it discriminated against working-class women: "The more I study the Bill the more astonished I am that such a large number of respected Members of Parliament should have found it possible to put their names to it. And, most of all, I was astonished that Liberal and Labour Members should have associated themselves with it. It is not merely an undemocratic Bill; it is worse. It is an anti-democratic Bill. It gives an entirely unfair representation to property, as against persons.... Of the 18,000 women voters it is calculated that 90,000 are working women, earning their living. What about the other half? The basic principle of the Bill is to deny votes to those who are upon the whole the best of their sex. We are asked by the Bill to defend the proposition that a spinster of means living in the interest of man-made capital is to have a vote, and the working man's wife is to be denied a vote even if she is a wage-earner and a wife." (17)

After leaving the Liberal Party in 1924 Churchill became Chancellor of the Exchequer in the Conservative Party government. Stanley Baldwin, the prime minister, wanted the party to develop a more liberal image and in March 1927 he suggested the enfranchisement of nearly five million women between the ages of twenty-one and thirty. This measure meant that women would constitute almost 53% of the British electorate. The Daily Mail complained that these impressionable young females would be easily manipulated by the Labour Party. (18)

Churchill was totally opposed to the move and argued that the affairs of the country ought not be put into the hands of a female majority. In order to avoid giving the vote to all adults he proposed that the vote be taken away from all men between twenty-one and thirty. Churchill lost the argument and in Cabinet and asked for a formal note of dissent to be entered in the minutes. There was little opposition in Parliament to the bill and it became law on 2nd July 1928. As a result, all women over the age of 21 could now vote in elections. (19)

Churchill's handling of the economy was blamed for the Conservative government's defeat in the 1929 General Election. Churchill's opposition to the party's policy on India also upset Stanley Baldwin, who was attempting to make the Conservatives a centre party. In 1931 when Baldwin, joined the National Government, he refused to allow Churchill to join the team because his views were considered to be too extreme. This included his idea that "democracy is totally unsuited to India" because they were "humble primitives". When the Viceroy of India, Edward Wood, told him that his opinions were out of date and that he ought to meet some Indians in order to understand their views, he rejected the suggestion: "I am quite satisfied with my views of India. I don't want them disturbed by any bloody Indian." (20)

In an article published in the Evening Standard in January, 1934, he declared that with the advent of universal suffrage the political and social class to which he belonged was losing its control over affairs and "a universal suffrage electorate with a majority of women voters" would be unable to preserve the British form of government. His solution was to go back to the nineteenth-century system of plural voting - those he deemed suitable would be given extra votes in order to outweigh the influence of women and the working class and produce the answer he wanted at General Elections. (21)

The Rise of Fascism

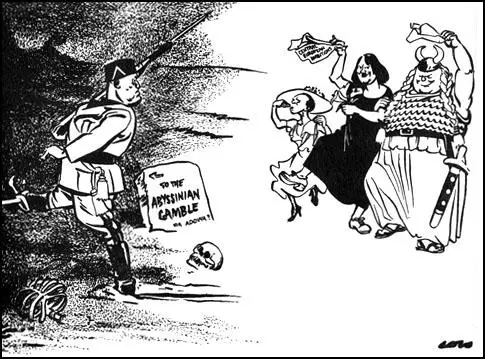

Churchill gave support to Benito Mussolini in his foreign adventures. On 3rd October 1935, Mussolini sent 400,000 soldiers to invade Abyssinia (Ethiopia). Haile Selassie, the ruler of appealed to the League of Nations for help, delivering an address that made him a worldwide figure. As might have been expected, given his views of black people, Churchill had little sympathy for one of the two last surviving independent African countries. He told the House of Commons: "No one can keep up the pretence that Abyssinia is a fit, worthy and equal member of a league of civilised nations." (22)

As the majority of the Ethiopian population lived in rural towns, Italy faced continued resistance. Haile Selassie fled into exile and went to live in England. Mussolini was able to proclaim the Empire of Ethiopia and the assumption of the imperial title by the Italian king Victor Emmanuel III. The League of Nations condemned Italy's aggression and imposed economic sanctions in November 1935, but the sanctions were largely ineffective since they did not ban the sale of oil or close the Suez Canal, that was under the control of the British. Despite the illegal methods employed by Mussolini, Churchill remained a loyal supporter. He told the Anti-Socialist Union that Mussolini was "the greatest lawgiver among living men". (23) He also wrote in The Sunday Chronicle that Mussolini was "a really great man". (24)

Sir Samuel Hoare, Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, joined with Pierre Laval, the prime minister of France, in an effort to resolve the crisis created by the Italian invasion of Abyssinia. The secret agreement, known as the Hoare-Laval Pact, proposed that Italy would receive two-thirds of the territory it conquered as well as permission to enlarge existing colonies in East Africa. In return, Abyssinia, was to receive a narrow strip of territory and access to the sea. This was "the policy that Churchill had favoured all along". (25)

Details of the Hoare-Laval plan was leaked to the press on 10th December, 1935. Clement Attlee, the leader of the Labour Party, moved a vote of censure. He accused Stanley Baldwin of winning the 1935 General Election on one policy and pursuing another. "There is the question of the honour of this country, and there is the honour of the Prime Minister... If you turn and run away from the aggressor, you kill the League, and you do worse than that... you kill all faith in the word of honour of this country." (26)

Sir Austen Chamberlain, the Conservative MP, condemned the Pact and said: "Gentlemen do not behave in such a way". The Conservative Chief Whip told Baldwin: "Our men won't stand for it". The Government withdrew the plan, and Hoare was forced to resign. Churchill decided to keep out of the debate in case it put him in a bad light. Attlee wrote to his brother: "I fear that we are in for a bad time. The Government has no policy and no convictions. I have never seen a collection of ministers more hopeless after so short a time since an election." (27)

Adolf Hitler knew that both France and Britain were militarily stronger than Germany. However, their failure to take action against Italy, convinced him that they were unwilling to go to war. He therefore decided to break another aspect of the Treaty of Versailles by sending German troops into the Rhineland. The German generals were very much against the plan, claiming that the French Army would win a victory in the military conflict that was bound to follow this action. Hitler ignored their advice and on 1st March, 1936, three German battalions marched into the Rhineland. Hitler later admitted: "The forty-eight hours after the march into the Rhineland were the most nerve-racking in my life. If French had then marched into the Rhineland we would have had to withdraw with our tails between our legs, for the military resources at our disposal would have been wholly inadequate for even a moderate resistance." (28)

The British government accepted Hitler's Rhineland coup. Sir Anthony Eden, the new foreign secretary, informed the French that the British government was not prepared to support military action. The chiefs of staff felt Britain was in no position to go to war with Germany over the issue. The Rhineland invasion was not seen by the British government as an act of unprovoked aggression but as the righting of an injustice left behind by the Treaty of Versailles. Eden apparently said that "Hitler was only going into his own back garden." (29)

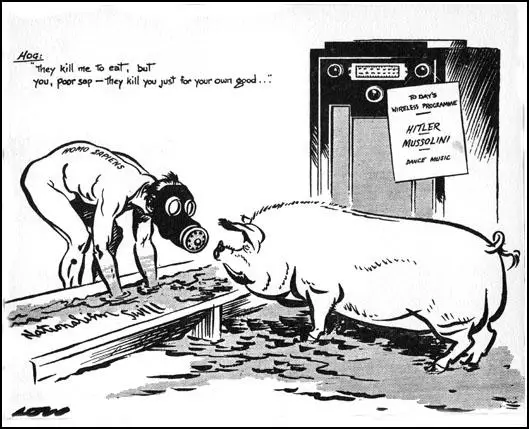

Winston Churchill agreed with the government position. In an article in the Evening Standard he praised the French for their restraint: "instead of retaliating with arms, as the previous generation would have, France has taken the correct course by appealing to the League of Nations". (30) In a speech in the House of Commons he supported the government's policy on appeasement and called on the League of Nations to invite Germany to state her grievances and her legitimate aspirations" so that under the League's auspices "justice may be done and peace preserved". (31)

Clement Attlee attacked Churchill, Baldwin and Eden and the Conservative government for the acceptance that Hitler was allowed to march into the Rhineland without any measures taken against Germany. He spoke of the dangers of accepting Hitler's actions as merely righting one of the punitive wrongs of Versailles. "In the last five years we have had quite enough of dodging difficulties, of using forms of words to avoid facing up to realities... I am afraid that you may get a patched-up peace and then another crisis next year." (32)

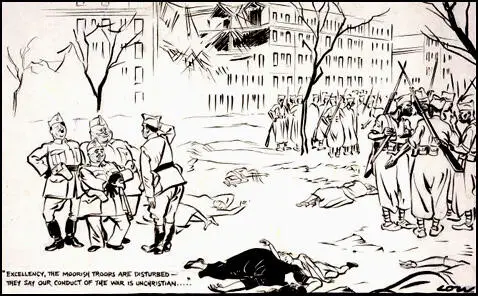

Winston Churchill also supported General Francisco Franco and his Fascist forces during the Spanish Civil War. He described the democratically elected Republican government as "a poverty stricken and backward proletariat demanding the overthrow of Church, State and property and the inauguration of a Communist regime." Against them stood the "patriotic, religious and bourgeois forces, under the leadership of the army, and sustained by the countryside in many provinces... marching to re-establish order by setting up a military dictatorship." (33)

Clement Attlee took a very different view of the conflict. He condemned Baldwin's policy towards Franco and described the war as "a fight for the soul of Europe" and claiming that non-intervention had become "a farce". For the first time he stated that the government was guilty of incremental steps of appeasement. If Britain had stood firm over Abyssinia there would not have been this trouble in Spain. There has been no policy in foreign affairs except the policy of giving way. The result of that is a world in anarchy." The government's policy, he maintained "is disastrous for world peace and... the government has not brought us nearer peace but has brought us closer and closer to the danger of war." (34)

As Geoffrey Best, the author of Churchill: A Study in Greatness (2001) has pointed out: "He (Churchill) was relatively unconcerned about what else went on in Europe. Eschewing the liberal-cum-socialist practice of bracketing together the two fascist dictators, he clung for long to a hope that Mussolini (whose regime in any case he correctly assessed as much less unpleasant than Hitler's) could be kept friendly or neutral in the forthcoming conflict. He was an anti-Nazi, not an anti-Fascist until very late in the day. He failed to give serious thought to the issues at stake in the Spanish Civil War and he did his own anti-Hitler campaign no good by appearing at that time to be pro-Franco." (35)

During this period Churchill was a supporter of the government's appeasement policy. In April 1936 he called on the League of Nations to invite Germany "to state her grievances and her legitimate aspirations" so that "justice may be done and peace preserved". (36) Churchill believed that the right strategy was to try and encourage Adolf Hitler to order the invasion of the Soviet Union. He wrote to Violet Bonham-Carter suggesting an alliance of Britain, France, Belgium and Holland to deter Germany from attacking in the west. He expected that Hitler would turn eastwards and attack the Soviet Union, and he proposed that Britain should stand aside while his old enemy Bolshevism was destroyed: "We should have to expect that the Germans would soon begin a war of conquest east and south and that at the same time Japan would attack Russia in the Far East. But Britain and France would maintain a heavily-armed neutrality." (37)

As late as September, 1937, Churchill was praising Hitler's domestic achievements. In an article published in The Evening Standard after praising Germany's achievements in the First World War he wrote: "One may dislike Hitler’s system and yet admire his patriotic achievement. If our country were defeated I hope we should find a champion as indomitable to restore our courage and lead us back to our place among the nations. I have on more than one occasion made my appeal in public that the Führer of Germany should now become the Hitler of peace." (38)

Churchill went further the following month. "The story of that struggle (Hitler's rise to power), cannot be read without admiration for the courage, the perseverance, and the vital force which enabled him to challenge, defy, conciliate or overcome, all the authority or resistances which barred his path.". He then considered the way Hitler had suppressed the opposition and set up concentration camps: "Although no subsequent political action can condone wrong deeds, history is replete with examples of men who have risen to power by employing stern, grim and even frightful methods, but who nevertheless, when their life is revealed as a whole, have been regarded as great figures whose lives have enriched the story of mankind. So may it be with Hitler." (39)

In a speech at the Conservative Party conference on 7th October, 1937, he made it clear that he opposed the government's policy on India but supported its appeasement policy: "I used to come here year after year when we had some differences between ourselves about rearmament and also about a place called India. So I thought it would only be right that I should come here when we are all agreed... let us indeed support the foreign policy of our Government, which commands the trust, comprehension, and the comradeship of peace-loving and law-respecting nations in all parts of the world." (40)

On 12th March, 1938, the German Army invaded Austria. Churchill, like the Government and most of his fellow politicians, found it difficult to decide how to react to what seemed to be a highly popular peaceful union of the two countries. During the debate in the House of Commons, Churchill did not advocate the use of force to remove German forces from Austria. Instead he called for was discussion between diplomats at Geneva and still continued to support the government's appeasement policy. (41)

The Munich Agreement

In September 1938, Neville Chamberlain met Adolf Hitler at his home in Berchtesgaden. Hitler threatened to invade Czechoslovakia unless Britain supported Germany's plans to takeover the Sudetenland. After discussing the issue with the Edouard Daladier (France) and Eduard Benes (Czechoslovakia), Chamberlain informed Hitler that his proposals were unacceptable. Neville Henderson, the British ambassador in Germany, pleaded with Chamberlain to go on negotiating with Hitler. He believed, like Lord Halifax, the Foreign Secretary, that the German claim to the Sudetenland in 1938 was a moral one, and he always reverted in his dispatches to his conviction that the Treaty of Versailles had been unfair to Germany. "At the same time, he was unsympathetic to feelers from the German opposition to Hitler seeking to enlist British support. Henderson thought, not unreasonably, that it was not the job of the British government to subvert the German government, and this view was shared by Chamberlain and Halifax". (42)

Benito Mussolini suggested to Hitler that one way of solving this issue was to hold a four-power conference of Germany, Britain, France and Italy. This would exclude both Czechoslovakia and the Soviet Union, and therefore increasing the possibility of reaching an agreement and undermine the solidarity that was developing against Germany. The meeting took place in Munich on 29th September, 1938. Desperate to avoid war, and anxious to avoid an alliance with Joseph Stalin and the Soviet Union, Chamberlain and Daladier agreed that Germany could have the Sudetenland. In return, Hitler promised not to make any further territorial demands in Europe. (43)

The meeting ended with Hitler, Chamberlain, Daladier and Mussolini signing the Munich Agreement which transferred the Sudetenland to Germany. "We, the German Führer and Chancellor and the British Prime Minister, have had a further meeting today and are agreed in recognizing that the question of Anglo-German relations is of the first importance for the two countries and for Europe. We regard the agreement signed last night and the Anglo-German Naval Agreement as Symbolic of the desire of our two peoples never to go to war with one another again. We are resolved that the method of consultation shall be the method adopted to deal with any other questions that may concern our two countries." (44)

Neville Henderson defended the agreement: "Germany thus incorporated the Sudeten lands in the Reich without bloodshed and without firing a shot. But she had not got all that Hitler wanted and which she would have got if the arbitrament had been left to war... The humiliation of the Czechs was a tragedy, but it was solely thanks to Mr. Chamberlain's courage and pertinacity that a futile and senseless war was averted." (45)

On 3rd October, 1938, Clement Attlee, the leader of the Labour Party, attacked the Munich Agreement in a speech in the House of Commons. "We have felt that we are in the midst of a tragedy. We have felt humiliation. This has not been a victory for reason and humanity. It has been a victory for brute force. At every stage of the proceedings there have been time limits laid down by the owner and ruler of armed force. The terms have not been terms negotiated; they have been terms laid down as ultimata. We have seen today a gallant, civilised and democratic people betrayed and handed over to a ruthless despotism. We have seen something more. We have seen the cause of democracy, which is, in our view, the cause of civilisation and humanity, receive a terrible defeat.... The events of these last few days constitute one of the greatest diplomatic defeats that this country and France have ever sustained. There can be no doubt that it is a tremendous victory for Herr Hitler. Without firing a shot, by the mere display of military force, he has achieved a dominating position in Europe which Germany failed to win after four years of war. He has overturned the balance of power in Europe. He has destroyed the last fortress of democracy in Eastern Europe which stood in the way of his ambition. He has opened his way to the food, the oil and the resources which he requires in order to consolidate his military power, and he has successfully defeated and reduced to impotence the forces that might have stood against the rule of violence." (46)

Winston Churchill now decided to break with the government over its appeasement policy and two days after Attlee's speech made his move. Churchill praised Chamberlain for his efforts: "If I do not begin this afternoon by paying the usual, and indeed almost invariable, tributes to the Prime Minister for his handling of this crisis, it is certainly not from any lack of personal regard. We have always, over a great many years, had very pleasant relations, and I have deeply understood from personal experiences of my own in a similar crisis the stress and strain he has had to bear; but I am sure it is much better to say exactly what we think about public affairs, and this is certainly not the time when it is worth anyone’s while to court political popularity."

Churchill went on to say the negotiations had been a failure: "No one has been a more resolute and uncompromising struggler for peace than the Prime Minister. Everyone knows that. Never has there been such instance and undaunted determination to maintain and secure peace. That is quite true. Nevertheless, I am not quite clear why there was so much danger of Great Britain or France being involved in a war with Germany at this juncture if, in fact, they were ready all along to sacrifice Czechoslovakia. The terms which the Prime Minister brought back with him could easily have been agreed, I believe, through the ordinary diplomatic channels at any time during the summer. And I will say this, that I believe the Czechs, left to themselves and told they were going to get no help from the Western Powers, would have been able to make better terms than they have got after all this tremendous perturbation; they could hardly have had worse."

It was now time to change course and form an alliance with the Soviet Union against Nazi Germany. "After the seizure of Austria in March we faced this problem in our debates. I ventured to appeal to the Government to go a little further than the Prime Minister went, and to give a pledge that in conjunction with France and other Powers they would guarantee the security of Czechoslovakia while the Sudeten-Deutsch question was being examined either by a League of Nations Commission or some other impartial body, and I still believe that if that course had been followed events would not have fallen into this disastrous state. France and Great Britain together, especially if they had maintained a close contact with Russia, which certainly was not done, would have been able in those days in the summer, when they had the prestige, to influence many of the smaller states of Europe; and I believe they could have determined the attitude of Poland. Such a combination, prepared at a time when the German dictator was not deeply and irrevocably committed to his new adventure, would, I believe, have given strength to all those forces in Germany which resisted this departure, this new design." (47)

Churchill's late conversion to anti-fascism is one of the reasons why he suffered such a heavy defeat in the 1945 General Election. The British people had the opportunity to show their gratitude for his role in winning the war, but they remembered his pro-fascism before October 1938. He suffered a humiliating defeat and Clement Attlee became the new prime minister. It was a high turnout with 72.8% of the electorate voting. With almost 12 million votes, Labour had 47.8% of the vote to 39.8% for the Conservatives. Labour made 179 gains from the Tories, winning 393 seats to 213. The 12.0% national swing from the Conservatives to Labour, remains the largest ever achieved in a British general election. (48)

References

(1) The New York Times (21st January, 1940)

(2) Clive Ponting, Winston Churchill (1994) page 394

(3) Geoffrey Best, Churchill: A Study in Greatness (2001) page 155

(4) Anthony James Gregor, Young Mussolini and the Intellectual Origins of Fascism (1979) page 196

(5) Tom Kington, The Guardian (13th October, 2009)

(6) Anthony Grayling, Ideas that Matter (2009) page 207

(7) Denis Mack Smith, Mussolini: A Biography (1982) page 50

(8) Adrian Lyttelton, The Seizure of Power: Fascism in Italy 1919-1929 (2009) pages 75-77

(9) Benito Mussolini, speech (3rd January 1925)

(10) Steven Jones, Antonio Gramsci (2006) page 24

(11) Winston Churchill, letter to Clementine Churchill (6th January, 1927)

(12) Martin Gilbert, Churchill: A Life (1991) page 480

(13) Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics (c. 340 BC)

(14) Winston Churchill, My Early Life (1930) page 373

(15) Winston Churchill, letter to Randolph Churchill (8th January, 1931)

(16) Robert Lloyd George, David and Winston: How a Friendship Changed History (2006) pages 70-71

(17) Winston Churchill, speech in the House of Commons (12th July, 1910)

(18) The Daily Mail (28th April, 1928)

(19) Clive Ponting, Winston Churchill (1994) page 314

(20) Clive Ponting, Winston Churchill (1994) page 338

(21) Winston Churchill, The Evening Standard (24th January, 1934)

(22) Winston Churchill, speech in the House of Commons (24th October 1935)

(23) Winston Churchill, speech (17th February, 1933)

(24) Winston Churchill, The Sunday Chronicle (26th May, 1935)

(25) Clive Ponting, Winston Churchill (1994) page 376

(26) Clement Attlee, speech in the House of Commons (19th December, 1935)

(27) Francis Beckett, Clem Attlee (2000) page 131

(28) Alan Bullock, Hitler: A Study in Tyranny (1962) page 345

(29) Frank McDonough, Neville Chamberlain, Appeasement and the British Road to War (1998) page 27

(30) Winston Churchill, The Evening Standard (13th March, 1936)

(31) Winston Churchill, speech in the House of Commons (6th April, 1936)

(32) Clement Attlee, speech in the House of Commons (26th March, 1936)

(33) Winston Churchill, The Evening Standard (10th August, 1936)

(34) Clement Attlee, speech in the House of Commons (29th October, 1936)

(35) Geoffrey Best, Churchill: A Study in Greatness (2001) page 155

(36) Winston Churchill, speech in the House of Commons (6th April, 1936)

(37) Winston Churchill, letter to Violet Bonham-Carter (25th May 1936)

(38) Winston Churchill, The Evening Standard (17th September 1937)

(39) Winston Churchill, The Evening Standard (14th October, 1937)

(40) Winston Churchill, speech at the Conservative Party conference at Scarborough (14th October, 1937)

(41) Winston Churchill, speech in the House of Commons (12th March, 1938)

(42) Peter Neville, Nevile Henderson : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

(43) Graham Darby, Hitler, Appeasement and the Road to War (1999) page 56

(44) Statement issued by Neville Chamberlain and Adolf Hitler after the signing of the Munich Agreement (30th September, 1938)

(45) Neville Henderson, Failure of a Mission (1940) page 167

(46) Clement Attlee, speech in the House of Commons (3rd October, 1938)

(47) Winston Churchill, speech in the House of Commons (5th October, 1938)

(48) Martin Pugh, Speak for Britain: A New History of the Labour Party (2010) pages 284-285

Previous Posts

The Death of Liberalism: Charles and George Trevelyan (19th December, 2016)

Donald Trump and the Crisis in Capitalism (18th November, 2016)

Victor Grayson and the most surprising by-election result in British history (8th October, 2016)

Left-wing pressure groups in the Labour Party (25th September, 2016)

The Peasant's Revolt and the end of Feudalism (3rd September, 2016)

Leon Trotsky and Jeremy Corbyn's Labour Party (15th August, 2016)

Eleanor of Aquitaine, Queen of England (7th August, 2016)

The Media and Jeremy Corbyn (25th July, 2016)

Rupert Murdoch appoints a new prime minister (12th July, 2016)

George Orwell would have voted to leave the European Union (22nd June, 2016)

Is the European Union like the Roman Empire? (11th June, 2016)

Is it possible to be an objective history teacher? (18th May, 2016)

Women Levellers: The Campaign for Equality in the 1640s (12th May, 2016)

The Reichstag Fire was not a Nazi Conspiracy: Historians Interpreting the Past (12th April, 2016)

Why did Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst join the Conservative Party? (23rd March, 2016)

Mikhail Koltsov and Boris Efimov - Political Idealism and Survival (3rd March, 2016)

Why the name Spartacus Educational? (23rd February, 2016)

Right-wing infiltration of the BBC (1st February, 2016)

Bert Trautmann, a committed Nazi who became a British hero (13th January, 2016)

Frank Foley, a Christian worth remembering at Christmas (24th December, 2015)

How did governments react to the Jewish Migration Crisis in December, 1938? (17th December, 2015)

Does going to war help the careers of politicians? (2nd December, 2015)

Art and Politics: The Work of John Heartfield (18th November, 2015)

The People we should be remembering on Remembrance Sunday (7th November, 2015)

Why Suffragette is a reactionary movie (21st October, 2015)

Volkswagen and Nazi Germany (1st October, 2015)

David Cameron's Trade Union Act and fascism in Europe (23rd September, 2015)

The problems of appearing in a BBC documentary (17th September, 2015)

Mary Tudor, the first Queen of England (12th September, 2015)

Jeremy Corbyn, the new Harold Wilson? (5th September, 2015)

Anne Boleyn in the history classroom (29th August, 2015)

Why the BBC and the Daily Mail ran a false story on anti-fascist campaigner, Cedric Belfrage (22nd August, 2015)

Women and Politics during the Reign of Henry VIII (14th July, 2015)

The Politics of Austerity (16th June, 2015)

Was Henry FitzRoy, the illegitimate son of Henry VIII, murdered? (31st May, 2015)

The long history of the Daily Mail campaigning against the interests of working people (7th May, 2015)

Nigel Farage would have been hung, drawn and quartered if he lived during the reign of Henry VIII (5th May, 2015)

Was social mobility greater under Henry VIII than it is under David Cameron? (29th April, 2015)

Why it is important to study the life and death of Margaret Cheyney in the history classroom (15th April, 2015)

Is Sir Thomas More one of the 10 worst Britons in History? (6th March, 2015)

Was Henry VIII as bad as Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin? (12th February, 2015)

The History of Freedom of Speech (13th January, 2015)

The Christmas Truce Football Game in 1914 (24th December, 2014)

The Anglocentric and Sexist misrepresentation of historical facts in The Imitation Game (2nd December, 2014)

The Secret Files of James Jesus Angleton (12th November, 2014)

Ben Bradlee and the Death of Mary Pinchot Meyer (29th October, 2014)

Yuri Nosenko and the Warren Report (15th October, 2014)

The KGB and Martin Luther King (2nd October, 2014)

The Death of Tomás Harris (24th September, 2014)

Simulations in the Classroom (1st September, 2014)

The KGB and the JFK Assassination (21st August, 2014)

West Ham United and the First World War (4th August, 2014)

The First World War and the War Propaganda Bureau (28th July, 2014)

Interpretations in History (8th July, 2014)

Alger Hiss was not framed by the FBI (17th June, 2014)

Google, Bing and Operation Mockingbird: Part 2 (14th June, 2014)

Google, Bing and Operation Mockingbird: The CIA and Search-Engine Results (10th June, 2014)

The Student as Teacher (7th June, 2014)

Is Wikipedia under the control of political extremists? (23rd May, 2014)

Why MI5 did not want you to know about Ernest Holloway Oldham (6th May, 2014)

The Strange Death of Lev Sedov (16th April, 2014)

Why we will never discover who killed John F. Kennedy (27th March, 2014)

The KGB planned to groom Michael Straight to become President of the United States (20th March, 2014)

The Allied Plot to Kill Lenin (7th March, 2014)

Was Rasputin murdered by MI6? (24th February 2014)

Winston Churchill and Chemical Weapons (11th February, 2014)

Pete Seeger and the Media (1st February 2014)

Should history teachers use Blackadder in the classroom? (15th January 2014)

Why did the intelligence services murder Dr. Stephen Ward? (8th January 2014)

Solomon Northup and 12 Years a Slave (4th January 2014)

The Angel of Auschwitz (6th December 2013)

The Death of John F. Kennedy (23rd November 2013)

Adolf Hitler and Women (22nd November 2013)

New Evidence in the Geli Raubal Case (10th November 2013)

Murder Cases in the Classroom (6th November 2013)

Major Truman Smith and the Funding of Adolf Hitler (4th November 2013)

Unity Mitford and Adolf Hitler (30th October 2013)

Claud Cockburn and his fight against Appeasement (26th October 2013)

The Strange Case of William Wiseman (21st October 2013)

Robert Vansittart's Spy Network (17th October 2013)

British Newspaper Reporting of Appeasement and Nazi Germany (14th October 2013)

Paul Dacre, The Daily Mail and Fascism (12th October 2013)

Wallis Simpson and Nazi Germany (11th October 2013)

The Activities of MI5 (9th October 2013)

The Right Club and the Second World War (6th October 2013)

What did Paul Dacre's father do in the war? (4th October 2013)

Ralph Miliband and Lord Rothermere (2nd October 2013)