Franco-Prussian War

The outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War took place on 16th July 1870. It was an attempt by Napoleon III to preserve the Second French Empire against the threat posed by German states of the North German Confederation led by the Prussian chancellor Otto von Bismarck. The International Workingmen's Association (IWMA) had declared at its conference the previous year that if war broke out a general strike should take place. However, Karl Marx had privately argued that this would end in failure as the "working-class... is not yet sufficiently organised to throw any decisive weight on to the scales". (1)

The Paris section of the IWMA immediately denounced the war. However, in Germany opinion was divided but the majority of socialists considered the war to be a defensive one and in the Reichstag only Wilhelm Liebknecht and August Bebel refused to vote for war credits and spoke vigorously against the annexation of Alsace-Lorraine. For this they were charged with treason and imprisoned. (2)

Karl Marx and the Franco-Prussian War

Marx believed that a German victory would help his long-term desire for a socialist revolution. He pointed out to Friedrich Engels that German workers were better organised and better disciplined than French workers who were greatly influenced by the ideas of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon: "The French need a drubbing. If the Prussians are victorious then the centralisation of the State power will give help to the centralisation of the working class... The superiority of the Germans over the French in the world arena would mean at the same time the superiority of our theory over Proudhon's and so on." (3)

A few days later Karl Marx issued a statement on behalf of the IWMA. "Whatever turn the impending horrid war may take, the alliance of the working classes of all countries will ultimately kill war. The very fact that while official France and Germany are rushing into a fratricidal feud, the workmen of France and Germany send each other messages of peace and goodwill; this great fact, unparalleled in the history of the past, opens the vista of a brighter future. It proves that in contrast to old society, with its economical miseries and its political delirium, a new society is springing up, whose International rule will be Peace, because its natural ruler will be everywhere the same - Labour! The Pioneer of that new society is the International Working Men's Association." (4)

Peace activists, John Stuart Mill and John Morley, congratulated Marx on his statement and arranged for 30,000 copies of his speech to be printed and distributed. Marx thought the war would provide the opportunity for revolution. He told Engels: "I have been totally unable to sleep for four nights now, on account of the rheumatism and I spend this time in fantasies about Paris, etc." He hoped for a German victory: "I wish this because the definite defeat of Bonaparte is likely to provoke Revolution in France, while the definite defeat of Germany would only protract the present state of things for twenty-years." (5)

In a letter to the American organiser of the IWMA, Friedrich Sorge, Marx made some predictions about the future that included the First World War and the Russian Revolution: "What the Prussian jackasses don't see is that the present war leads just as necessarily to war between Germany and Russia as the war of 1866 led to war between Prussia and France. That is the best result that I expect of it for Germany. Prussianism as such has never existed and cannot exist other than in alliance and in subservience to Russia. And this War No. 2 will act as the mid-wife of the inevitable revolution in Russia." (6)

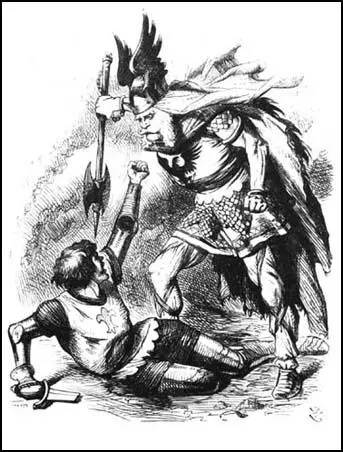

The Battle of Sedan

The war went badly for Napoleon III and he was heavily defeated at the Battle of Sedan. On 4th September, 1870, a republic was proclaimed in Paris. Adolphe Thiers, a former prime minister and an opponent of the war, was elected chief executive of the new French government. (7)

Theirs now aged 74, appointed a provisional government of conservative views and then travelled to London and attempted to negotiate an alliance with Britain. William Gladstone refused and when he arrived back in Paris on 31st October 1870, he was accused of treason. Felix Pyat, a radical socialist organized demonstrations against Thiers, whom he accused of threatening to sell France to the Germans. (8)

Karl Marx, who had been slow to attack Bismark because of his "pure German patriotism to which both he and Engels were always conspicuously prone" and the International Workingmen's Association issued a statement "protesting against the annexation, denouncing the dynastic ambitions of the Prussian King, and calling upon the French workers to unite with all defenders of democracy against the common Prussian foe." (9)

Marx later pointed out that it was "An absurdity and an anachronism to make military considerations the principle by which the boundaries of nations are to be fixed? If this rule were to prevail, Austria would still be entitled to Venetia and the line of the Minicio, and France to the line of the Rhine, in order to protect Paris, which lies certainly more open to an attack from the northeast than Berlin does from the southwest. If limits are to be fixed by military interests, there will be no end to claims, because every military line is necessarily faulty, and may be improved by annexing some more outlying territory; and, moreover, they can never be fixed finally and fairly, because they always must be imposed by the conqueror upon the conquered, and consequently carry within them the seed of fresh wars." (10)

Paris Commune

In March 1871, the government made an attempt to disarm the Paris National Guard, a volunteer citizen force which showed signs of radical sympathies. It refused to give up its arms, declared its autonomy, deposed the officials of the provisional government, and elected a revolutionary committee of the people as the true government of France. Adolphe Thiers now fled to Versailles. Governments all over Europe were concerned by what was happening in Europe. The Times reported complained against "this dangerous sentiment of the Democracy, this conspiracy against civilisation in its so-called capital". (11)

The new government called itself the Paris Commune and attempted to run the city. Isaiah Berlin argues the committee was a mixture of different political opinions but did include the followers of Mikhail Bakunin, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and Louis Auguste Blanqui. The Communards had difficulty keeping control of the national guard and 28th March, on the day of the election, General Jacques Leon Clément-Thomas and General Claude Lecomte were murdered. Doctor Guyon, who examined the bodies shortly afterwards, found forty balls in the body of Clément-Thomas and nine balls in the back of Lecomte.

Adolphe Thiers now based in Versailles urged Parisians to abstain from voting. When the voting was finished, 233,000 Parisians had voted, out of 485,000 registered voters. In upper-class neighborhoods many refused to take part in the election with over 70 per cent refusing to vote. But in the working-class neighborhoods, turnout was high. Of the ninety-two Communards elected by popular suffrage, seventeen were members of the IWMA. It was agreed that Marx should draft an "Address to the People of Paris" but he was suffering from bronchitis and liver trouble and was unable to carry out the work. (12)

The Communards had difficulty keeping control of the national guard and on the day of the election, General Jacques Leon Clément-Thomas and General Claude Lecomte , two men blamed for being severe disciplinarians, were murdered. Doctor Guyon, who examined the bodies shortly afterwards, found forty balls in the body of Clément-Thomas and nine balls in the back of Lecomte. (13)

At the first meeting of the Commune, the members adopted several proposals, including an honorary presidency for Louis Auguste Blanqui; the abolition of the death penalty; the abolition of military conscription; a proposal to send delegates to other cities to help launch communes there. It was also stated that no military force other than the National Guard, made up of male citizens, could be formed or introduced into the capital. School children in the city were provided with free clothing and food. David McLellan suggests that the actual measures passed by the commune were reformist rather than revolutionary, with no attack on private property: employers were forbidden on the penalty of fines to reduce wages... and all abandoned businesses were transferred to co-operative associations." (14)

Karl Marx believed the actions of the Communards were revolutionary: "Having once got rid of the standing army and the police – the physical force elements of the old government – the Commune was anxious to break the spiritual force of repression... by the disestablishment and disendowment of all churches as proprietary bodies. The priests were sent back to the recesses of private life, there to feed upon the alms of the faithful in imitation of their predecessors, the apostles. The whole of the educational institutions were opened to the people gratuitously, and at the same time cleared of all interference of church and state. Thus, not only was education made accessible to all, but science itself freed from the fetters which class prejudice and governmental force had imposed upon it." (15)

Although only males were allowed to vote in the elections, several women were involved in the Paris Commune. Nathalie Lemel and Élisabeth Dmitrieff, created the Women's Union for the Defense of Paris and Care of the Wounded. The group demanded gender and wage equality, the right of divorce for women, the right to secular education, and professional education for girls. Anne Jaclard and Victoire Léodile Béra founded the newspaper Paris Commune and Louise Michel, established a female battalion of the National Guard. (16)

The Committee was given extensive powers to hunt down and imprison enemies of the Commune. Led by Raoul Rigault, it began to make several arrests, usually on suspicion of treason. Those arrested included Georges Darboy, the Archbishop of Paris, General Edmond-Charles de Martimprey and Abbé Gaspard Deguerry. Rigault attempted to exchange these prisoners for Louis Auguste Blanqui who had been captured by government forces. Despite lengthy negotiations, Adolphe Thiers refused to release him.

On 22nd May 1871, Marshal Patrice de MacMahon and his government troops entered the city. The Committee of Public Safety issued a decree: "To arms! That Paris be bristling with barricades, and that, behind these improvised ramparts, it will hurl again its cry of war, its cry of pride, its cry of defiance, but its cry of victory; because Paris, with its barricades, is undefeatable ...That revolutionary Paris, that Paris of great days, does its duty; the Commune and the Committee of Public Safety will do theirs!" (17)

It is estimated that about fifteen to twenty thousand persons, including many women and children, responded to the call of arms. The forces of the Commune were outnumbered five-to-one by Marshal MacMahon's forces. They made their way to Montmartre, where the uprising had begun. The garrison of one barricade, was defended in part by a battalion of about thirty women, including Louise Michel. The soldiers captured 42 guardsmen and several women, took them to the same house on Rue Rosier where generals Clement-Thomas and Lecomte had been executed, and shot them.

Large numbers of the National Guard changed into civilian clothes and fled the city. It is estimated that this left only about 12,000 Communards to defend the barricades. As soon as they were captured they were executed. Raoul Rigaut responded by killing his prisoners, including the Archbishop of Paris and three priests. Soon afterwards Rigaut was captured and executed and the rebellion came to an end soon afterwards on 28th May. As Isaiah Berlin pointed out: "The retribution which the victorious army exacted took the form of mass executions; the white terror, as is common in such cases, far outdid in acts of bestial cruelty the worst excesses of the regime whose misdeeds it had come to end." (18)

According to Marx this is what always happens when the masses attempt to take control of society: "The civilization and justice of bourgeois order comes out in its lurid light whenever the slaves and drudges of that order rise against their masters. Then this civilization and justice stand forth as undisguised savagery and lawless revenge. Each new crisis in the class struggle between the appropriator and the producer brings out this fact more glaringly... The self-sacrificing heroism with which the population of Paris – men, women, and children – fought for eight days after the entrance of the Versaillese, reflects as much the grandeur of their cause, as the infernal deeds of the soldiery reflect the innate spirit of that civilization, indeed, the great problem of which is how to get rid of the heaps of corpses it made after the battle was over!" (19)

In his best-selling pamphlet, The Civil War in France (1871), Karl Marx admitted that the International Workingmen's Association was heavily involved in the Paris Commune. Jules Favre, the recently reinstated foreign minister in France, asked all European governments to outlaw the IWMA. A French newspaper identified Marx as the "supreme chief" of the conspirators, alleging that he had "organised" the uprising from London. It claimed that the IWMA had seven million members. (20)

Other European governments also urged the punishment of IWMA members. Spain agreed to extradite those involved in the Paris Commune. Giuseppe Mazzini, the leader of the Italian nationalist movement, joined in the calls for the arrest of Marx, who he described as "a man of domineering disposition; jealous of the influence of others; governed by no earnest, philosophical, or religious belief; having, I fear more elements of anger than of love in his nature". (21)

British newspapers also complained about the dangers posed by Karl Marx. The Times warned of the possibility of Marx having an influence on the working-class. It feared that solid English trade unionists who wanted nothing more than "a fair day's wage for a fair day's work" might be corrupted by "strange theories" imported from abroad. (22) Marx wrote to Ludwig Kugelmann that "I have the honour to be this moment the most abused and threatened man in London." (23)

The German ambassador urged Granville Leveson-Gower, the British Foreign Secretary, to treat Marx as a common criminal because of his outrageous "menaces to life and property". After consulting with William Gladstone, the Prime Minister, he replied that "extreme socialist opinions are not believed to have gained any hold upon the working men of this country" and "no practical steps with regard to foreign countries are known to have been taken by the English branch of the Association." (24)

The publication of The Civil War in France (1871) upset several British trade union leaders and George Odger resigned from the General Council of International Workingmen's Association. It has been argued that the passing of the 1867 Reform Act had made the working class less radical. After the Paris Commune, the only areas where the IWMA made progress was in the the strongholds of anarchism: Spain and Italy. (25)

The French government signed the Treaty of Frankfurt in May 1871. This established the frontier between the French Third Republic and the German Empire, This resulted in France losing Alsace and Lorraine, Strasburg and the great fortress of Metz to Germany and involved the ceding of 1,694 villages and cities under French control to Germany. (26)

German Unification

After his victory over the French, Otto von Bismarck, the President of Prussia, acted immediately to secure the unification of Germany. He negotiated with representatives of the southern German states, offering special concessions if they agreed to unification. The new German Empire was a federation made up of 25 constituent states. Germany occupied an area of 208,825 square miles and had a population of more than 41 million. Whereas in 1871, Britain occupied 94,525 square miles with a population of 21 million. Jonathan Steinberg has argued: "The genius-statesmen had transformed European politics and had unified Germany in eight and a half years. And he had done so by sheer force of personality, by his brilliance, ruthlessness, and flexibility of principle." (27)

Bismarck gained support for unification by allowing all men over the age of 25 the vote. Bismarck came to the decision that the best way of preventing socialism was by introducing a series of social reforms including old age pensions. In 1881 he announced that "those who are disabled from work by age and invalidity have a well-grounded claim to care from the state." When the issue was debated Bismarck was described by his critics as a socialist. He replied: "Call it socialism or whatever you like. It is the same to me." It has been argued that Bismarck's intention was to "forge a bond between workers and the state so as to strengthen the latter, to maintain traditional relations of authority between social and status groups, and to provide a countervailing power against the modernist forces of liberalism and socialism." (28)

In 1883 Bismarck introduced a health insurance system that provided payments when people were sick and unable to work. Participation was mandatory and contributions were taken from the employee, the employer and the government. The German system provided contributory retirement benefits and disability benefits as well. Germany was therefore the first country in the world to provide a comprehensive system of income security based on social insurance principles.

Bismarck explained: "The real grievance of the worker is the insecurity of his existence; he is not sure that he will always have work, he is not sure that he will always be healthy, and he foresees that he will one day be old and unfit to work. If he falls into poverty, even if only through a prolonged illness, he is then completely helpless, left to his own devices, and society does not currently recognize any real obligation towards him beyond the usual help for the poor, even if he has been working all the time ever so faithfully and diligently. The usual help for the poor, however, leaves a lot to be desired, especially in large cities, where it is very much worse than in the country." (29)

Bismarck believed that this insurance system would increase productivity, and focus the political attentions of German workers on supporting his government. It also resulted in a rapid decline of German emigration to America. He also hoped that it would reduce support for the socialists. After the passing of the Old Age and Disability Insurance Law in 1889, Bismarck thought it was safe to legalize the Social Democratic Party. (30)

Primary Sources

(1) Karl Marx, statement on behalf of the International Workingmen's Association (23rd July 1870)

Whatever turn the impending horrid war may take, the alliance of the working classes of all countries will ultimately kill war. The very fact that while official France and Germany are rushing into a fratricidal feud, the workmen of France and Germany send each other messages of peace and goodwill; this great fact, unparalleled in the history of the past, opens the vista of a brighter future. It proves that in contrast to old society, with its economical miseries and its political delirium, a new society is springing up, whose International rule will be Peace, because its natural ruler will be everywhere the same - Labour! The Pioneer of that new society is the International Working Men's Association.

(2) Karl Marx, letter to Friedrich Sorge (1st September, 1870)

What the Prussian jackasses don't see is that the present war leads just as necessarily to war between Germany and Russia as the war of 1866 led to war between Prussia and France. That is the best result that I expect of it for Germany. Prussianism as such has never existed and cannot exist other than in alliance and in subservience to Russia. And this War No. 2 will act as the mid-wife of the inevitable revolution in Russia.

(3) Karl Marx, The Civil War in France (1871)

An absurdity and an anachronism to make military considerations the principle by which the boundaries of nations are to be fixed? If this rule were to prevail, Austria would still be entitled to Venetia and the line of the Minicio, and France to the line of the Rhine, in order to protect Paris, which lies certainly more open to an attack from the northeast than Berlin does from the southwest. If limits are to be fixed by military interests, there will be no end to claims, because every military line is necessarily faulty, and may be improved by annexing some more outlying territory; and, moreover, they can never be fixed finally and fairly, because they always must be imposed by the conqueror upon the conquered, and consequently carry within them the seed of fresh wars

Student Activities

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)