Carl Jung

Carl Jung, only surviving child of Paul Achilles Jung and Emilie Preiswerk, was born in Thurgau, a canton of Switzerland, on 26th July 1875. His father was a rural pastor in the Swiss Reformed Church. His mother suffered from depression when he was a child and spent a lot of time in her bedroom where she believed she was visited by spirits. He enjoyed a better relationship with his father who was more stable and predictable. (1)

Jung was a lonely and withdrawn child. He attended the Humanistisches Gymnasium in Basel but at the age of twelve he was knocked unconscious by another boy. He was taken home and he recalled that he thought "now you won't have to go to school anymore." He remained at home for the next six months being taught by his father. Eventually, he was able to return to school. In his autobiography he said this difficult period helped him understand "what a neurosis is." (2)

According to Peter Gay: "Jung left the most contradictory impressions on those who knew him; he was sociable but difficult, amusing at times and taciturn at others, outwardly self-confident yet vulnerable to criticism... He was also beset by tormenting religious crises. Whatever his private conflicts, from his youth, Jung exuded a sense of power, with his large frame, sturdy build, strongly carved Teutonic face, and torrential eloquence." (3)

Carl Jung at University of Basel

Carl Jung became an omnivorous reader of philosophy. This led to clashes with his father and he stopped going to church. As a result of his early problems at school he developed an interest in psychiatry and in 1895 he began studying medicine at the University of Basel. Soon after leaving home his father was diagnosed with terminal cancer. "His father's death, as well as conferring on him the responsibility as family manager; also liberated something else in his nineteen-year-old self. To Jung's fellow students at university it was an astonishing change. The countrified bookworm suddenly joined in the swing of campus life." (4)

At university he became interested in spiritualism and mesmerism. This included attended a number of spiritualist séances. Just before his final examination, Jung happened to read the introduction of a book on psychiatry by Richard von Krafft-Ebing and "suddenly understood the connection between psychology or philosophy and medical science." At this point he decided to specialize in psychiatry. (5)

Sigmund Freud

In 1900, he began working in a psychiatric hospital in Zurich, with Eugen Bleuler. His dissertation, published in 1903, was titled On the Psychology and Pathology of So-Called Occult Phenomena. Bleuler was a follower of Sigmund Freud and he gave Jung a copy of his book, The Interpretation of Dreams (1900). The book left its mark on Jung and incorporated Freud's ideas into his own work. (6)

Jung married Emma Rauschenbach in 1903. She was seven years his junior and the elder daughter of a wealthy industrialist in Switzerland, Johannes Rauschenbach-Schenck. Upon his death in 1905, his two daughters and their husbands became owners of the business. Jung's brother-in-law became the principal proprietor, but the Jungs remained shareholders in a thriving business that ensured the family's financial security. They had five children: Agathe, Gret, Franz, Marianne, and Helene. (7)

In 1904, Jung published Studies in Word Association.This was followed by The Psychology of Dementia Pracecox (1906). In this book he singled out the "brilliant conceptions" of Freud who had "not yet received his just recognition and appreciation". He warned that just because Freud was expressing ideas that shocked and disgusted people we should not act "like those famous men of science who disdained to look through Galileo's telescope." (8)

Jung also read Freud's Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality (1905). In the book Freud put together, from what he had learned by analyses of patients and other sources, all he knew about the development of the sexual instinct from its earliest beginnings in childhood. Freud provided "the foundation for his theory of neuroses, the explanation of the need for repression and the source of emotional energy underlying conscious and unconscious drives and behaviour which he named libido." (9)

In April 1906, Jung wrote to Freud praising his work. He insisted that Freud had "reported nothing but the truth from the hitherto unexplored regions of our discipline." Jung also enclosed some articles he had published. Freud replied a few days later saying how much he liked his work and suggested they carried out research together. "I count confidently on your often being in the position of corroborating me, and will also gladly see myself corrected." (10)

The two men began a regular correspondence. Freud was so impressed with Jung that he wrote in October, 1906, that he hoped that one day he would take over the leadership of the movement. "He (Freud) did not hesitate to cast himself in the part of an aging founder ready to hand on the torch to younger hands." (11) Even if he should not live to see that triumph, "my pupils, I hope, will be there, and I hope, further, that whoever can bring himself to overcome inner resistance for the sake of truth will gladly count himself among my pupils and eradicate the residues of indecisiveness from his thought." (12)

Jung did not meet Freud until 27th February, 1907. Jung and Ludwig Binswanger, his colleague, were invited to a family meal. Martin Freud later recalled: "He (Jung) never made the slightest attempt to make polite conversation with mother or us children but pursued the debate which had been interrupted by the call to dinner. Jung on these occasions did all the talking and father with unconcealed delight did all the listening." According to Martin his father and Jung talked for about thirteen hours without stopping. (13)

Binswanger also wrote about the meeting. He stated that he stood in awe of Freud's "greatness and dignity" but was neither frightened nor intimidated by his host's "distaste for all formality and etiquette, his personal charm, his simplicity, casual openness and goodness, and, not least, his humour." He was also impressed with the behaviour of his children: "The flock of children conducted itself very quietly at table, although, here, too, a completely unconstrained tone dominated." (14)

Jung also attended a meeting of the "Wednesday Psychological Society" on 7th March. Members of the group included Alfred Adler, Otto Rank, Max Eitingon, Wilhelm Stekel, Karl Abraham, Hanns Sachs and Sandor Ferenczi. That evening Ernest Jones, a friend from England, was at the meeting and later claimed that Jung had "a breezy personality" endowed with "a restlessly active and quick brain" he "was forceful or even domineering in temperament". Jones commented that Freud was attracted to "Jung's vitality". (15)

People found Carl Jung a very attractive man that had the ability to hold people's attention. One of Freud's son's described him as having a commanding presence: "He was very tall and broad-shouldered, holding himself more like a soldier than a man of science and medicine. His head was purely Teutonic with a strong chin, a small mustache, blue eyes and thin close-cropped hair." (16)

In one letter Jung admitted to Freud that that their relationship had an "undeniable erotic undertone" that was both "repulsive and ridiculous". Freud, who was at the time was musing on his own homoerotic feelings for Wilhelm Fliess, fully understood Jung's revelation. He added that his powerful distaste for this quasi-religious infatuation to an incident in his childhood, when, "as a boy, I succumbed to a homosexual attack by a man I had formerly revered." (17)

In 1908, Freud appointed Jung as editor of the newly founded Yearbook for Psychoanalytical and Psychopathological Research. It has been claimed: "Freud needed Jung's huge energy, intellect and gift for publicity to push forward the expansion of what was rapidly becoming a psychoanalytical movement. It was also no hindrance that Jung was a non-Jew and a non-Austrian. Psychoanalysis could no longer be dismissed, in anti-Semitic terms, as a strange, probably decadent mishmash of psychology and sexuality dreamt up by a coterie of Viennese Jews." (18)

Ernest Jones suggested that Freud's followers should hold an international conference. The meeting took place in Salzburg on 27th April, 1908. Jung named it the "First Congress for Freudian Psychology". The following year the group formed the International Psychoanalytical Congress at Nuremberg in March 1910. Its first President was Carl Jung. "To begin with, Jung with his commanding presence and soldierly bearing looked the part of the leader. With his psychiatric training and position, his excellent intellect and his evident devotion to the work, he seemed far better qualified for the post than anyone else." (19)

Visit to North America

Granville Stanley Hall, the President of Clark University, in Worcester, Massachusetts, had done much to popularize psychology, especially child psychology, in in the United States, and was the author of Adolescence: Its Psychology and Its Relations to Physiology, Anthropology, Sociology, Sex, Crime, Religion and Education (1904). Hall was a great supporter of Freud and in December, 1908, he invited him to deliver a series of lectures at the university. (20)

Freud accepted the invitation and asked Carl Jung if he wanted to join him on the journey. In August 1909, Freud, Jung, and Sandor Ferenczi sailed to America. Ernest Jones travelled from Toronto, where he was working, to join them. The following month Freud gave five lectures in German. He later recalled: "At that time I was only fifty-three. I felt young and healthy, and my short visit to the new world encouraged my self-respect in every way. In Europe I felt as though I were despised; but over there I found myself received by the foremost men as an equal." (21)

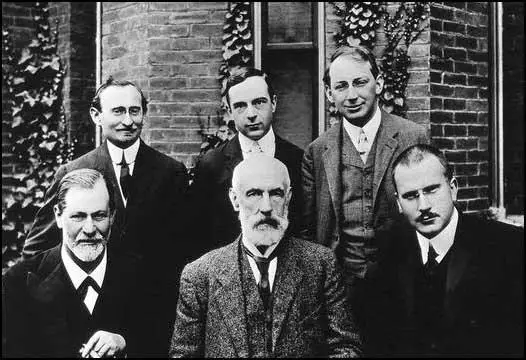

Front row, Sigmund Freud, Granville Stanley Hall and Carl Jung (September 1909)

Freud admitted that he had not expected the reception he received. "We found to our great surprise that the unprejudiced men in that small but reputable university knew all the psychoanalytic literature... In prudish America one could, at least in academic circles, freely discuss and scientifically treat everything that is regarded as improper in ordinary life.... Psychoanalysis was not a delusion any longer; it had become a valuable part of reality." (22)

Dispute with Carl Jung

In the early stages of their relationship Sigmund Freud played the role of mentor and Carl Jung as his pupil. In response to this, Freud "to the irritation of others in the psychoanalytic movement, was quick to award Jung the role of heir apparent". It was not long before differences in their respective approaches to sexuality became clear. "Jung refused to accept Freud's all-pervasive account, seeking to understand the main force in human life as a more generalized energy. He was also open to a more mystical and religious approach to life: attitudes that Freud would dismiss as mere illusion." (23)

During the boat trip to the United States the two men spent a lot of time discussing Freud's theories. Ernest Jones reported the two men began to argue about the importance of the Oedipus complex. Freud and Jung were also involved in the study of religion: "The revival of his interest in religion was to a considerable extent connected with Jung's extensive excursion into mythology and mysticism. They brought back opposite conclusions from their studies." (24)

Freud found this very disturbing as he treated Jung as his favourite son. He told him in a letter that "I am very fond of you" but he added "I have learned to subordinate that element." Freud admitted to Jung that it was his "egotistical intention, which I confess frankly" to "install" Jung as the person who would continue and complete "my work". As a "strong independent personality" he seemed best equipped for the task. (25)

Peter Gay, the author of Freud: A Life for Our Time (1989), explains the three reasons why he chose Jung as the future leader of the movement. "Jung was not Viennese, not old, and, best of all, not Jewish, three negative assets that Freud found irresistible." (26) Over and over, in his letters to his Jewish intimates, he praised Jung for doing "splendid, magnificent" work in editing, theorizing, or attacking the enemies of psychoanalysis. He told Sandor Ferenczi: "Now don't be jealous, and include Jung in your calculations. I am more convinced than ever that he is the man of the future." (27)

In a series of letters Jung questioned Freud's definition of libido. Jung believed that the word should not only stand for the sexual drives, but for a general mental energy. Freud wrote to Ferenzi that things were "storming and raging again" about Jung's "erotic and religious realm". (28) However, two weeks later he said he had "rapidly made it up with him, since, after all, I was not angry but only concerned." (29) Freud did what he could to keep Jung's loyalty. On 6th March, 1910, he wrote that his "dear son" should "rest easy" and told him of the great triumphs he would enjoy. "I leave you more to conquer than I could manage myself, all of psychiatry and the approval of the civilized world, which is accustomed to regard me as a savage." (30)

Jung continued to disagree with Freud and in a plea for autonomy he quoted the words of Friedrich Nietzsche: "One poorly repays a teacher if one remains only the pupil." (31) Freud responded with sadness: "If a third party should read this passage, he would ask me when I had undertaken to suppress you intellectually, and I would have to say: I do not know.... Rest assured of the tenacity of my affective interest, and keep thinking of me in a friendly way, even if you write only rarely." (32)

In May 1912 Freud and Jung became involved in a dispute over the meaning of the incest taboo. Freud now realised that his relationship was at breaking point. Freud now had a meeting with his loyal followers, Ernest Jones, Otto Rank, Karl Abraham, Max Eitingon, Sandor Ferenczi and Hanns Sachs and it was decided to form a "united small body, designed... to guard the kingdom and policy of the master". (33)

The final break came when Jung made a speech at Fordham University where he rejected Freud's theories of childhood sexuality, the Oedipus complex and the role of sexuality in the formation of neurotic illness. In a letter to Freud, he argued that his vision of psychoanalysis had managed to win over many people who had hitherto been put off by "the problem of sexuality in neurosis". He said that he hoped that friendly personal relations with Freud would continue, but in order for that to happen he did not want resentment but objective judgments. "With me this is not a matter of caprice, but of enforcing what I consider to be true." (34)

The publication of Jung's book, The Psychology of the Unconscious (1912) also caused problems. The book illustrated the differences between the two men. Jung disagreed with Freud about the importance of sexual development. He believed that Freud underestimated the role played by collective unconscious: the part of unconscious that contains memories and ideas inherited from our ancestors. Jung also argued that libido alone was not responsible for the formation of the core personality. Freud responded by criticizing Jung for "being gullible about occult phenomena and infatuated with oriental religions". (35)

In late November 1912, Jung and Freud met at a conference in Munich. The reunion was marred by one of Freud's fainting spells. This was a repeat on what happened at their last meeting. "Suddenly, to our consternation, he fell on the floor in a dead faint. The sturdy Jung swiftly carried him to a couch in the lounge, where he soon revived." (36) In letters he sent to friends, Freud claimed that "the principal agent in his fainting was a psychological conflict". However, in a letter to Jung he said the fainting was caused by a migraine. (37)

After receiving a letter from Jung in December, 1912, Freud told Ernest Jones that "he (Jung) seems all out of his wits, he is behaving quite crazy" and the "reconciliation" of November "has left no trace with him". However, he added he wanted no "official separation", for the sake of "our common interest" and advised Jones to take "no more steps to his conciliation". He suggested Jones did not make contact with Jung as he would probably say "I was the neurotic... It is the same mechanism and the identical reaction as in Adler's case." (38)

Lou Andreas-Salomé took the side of Sigmund Freud over Carl Jung: "A single look at these two will reveal which of them is the most dogmatic, the more power-loving. Where with Jung a kind of robust gaiety, abundant vitality, spoke through his booming laughter two years ago, his seriousness now holds pure aggressiveness, ambition, mental brutality." (39)

In 1913 Freud published a series of essays entitled Totem and Taboo. The final essay is an attack on Jung's ideas on religion that he considered to reflect the "roots of religion in primitive needs, primitive notions, and no less primitive acts." Jung wrote in criticism of Freud: "The strange thing is that man will not learn that God is his father. That is what Freud would never learn, and what all those who share his outlook forbid themselves to learn." (40)

Freud saw Jung for the last time in September 1913, at the Fourth International Psychoanalytical Congress in Munich. Jung gave a talk on psychological types, the introverted and extraverted type in analytical psychology. This constituted the introduction of some of the key concepts which came to distinguish Jung's work from Freud's in the next few years. Freud later commented: "We parted with no wish to see one another again." Eventually, in 1914, Jung resigned as President of the International Psychoanalytic Association. (41)

Introversion and Extraversion

In Psychological Types: The Psychology of Individuation (1921) Jung was one of the first people to define introversion and extraversion. According to Jung the typical introvert is focused on the internal world of reflection and dreaming. Thoughtful and insightful, the introvert can sometimes be uninterested in joining the activities of others. They are usually more interested in books than people. They tend to be reserved and distant except with intimate friends. The extravert is focused on the outside world of objects, sensory perception and action. Energetic and lively, the extrovert craves excitement, takes chances and acts on the spur of the moment and generally embraces change. (42)

However, as Hans Eysenck has pointed out: "Contrary to common belief, he (Jung) did not originate the terms extraversion and introversion, but took them over from common European usage, where they had been widely employed for over two hundred years. Neither was he the first to describe these temperamental types, as is often believed; as pointed out before, they go back at least as far as Galen and probably even further, and all that can be said of Jung's own contribution to this typology is that what is new in it is not true, and what is true is not new." (43)

Jung believed that extroverts and introverts were expressing neurotic behaviour. Research has shown that is that the introvert and extravert are merely extremes on a scale, not actually two distinct types. "They differ as do tall and short by departing in both directions from some middle condition: most people are ambiverts, neither introverts nor extraverts but sometimes one, sometimes the other." (44)

Jungian Theory

Carl Jung believed we were influenced by our collective consciousness. "The great problems of life - sexuality, of course, among others - are always related to the primordial images of the collective unconscious." He argued that there was a limit to rational thought: "We should not pretend to understand the world only by the intellect; we apprehend it just as much by feeling. Therefore, the judgment of the intellect is, at best, only the half of truth, and must, if it be honest, also come to an understanding of its inadequacy." (45)

According to Jung this had an impact on our decision making process: "The great decisions of human life have as a rule far more to do with the instincts and other mysterious unconscious factors than with conscious will and well-meaning reasonableness. The shoe that fits one person pinches another; there is no recipe for living that suits all cases. Each of us carries his own life-form - an indeterminable form which cannot be superseded by any other." (46)

Jung believed strongly that there were strong psychological differences between men and women. In Women In Europe (1927) he wrote: "It is a woman's outstanding characteristic that she can do anything for the love of a man. But those women who can achieve something important for the love of a thing are most exceptional, because this does not really agree with their nature. Love for a thing is a man's prerogative. But since masculine and feminine elements are united in our human nature, a man can live in the feminine part of himself, I and a woman in her masculine part. None the less the feminine element in man is only something in the background, as is the masculine element in woman. If one lives out the opposite sex in oneself one is living in one's own background, and one's real individuality suffers. A man should live as a man and a woman as a woman." (47)

Jung was extremely hostile to the Soviet Union. He argued hat the state "swallowed up" people's "religious forces" and therefore that the state had "taken the place of God" and therefore was comparable to a religion in which "state slavery is a form of worship". Jung observed that "stage acts of the state" are comparable to religious displays: "Brass bands, flags, banners, parades and monster demonstrations are no different in principle from ecclesiastical processions, cannonades and fire to scare off demons". (48)

Carl Jung and Nazi Germany

On 30th January, 1933, Adolf Hitler was appointed Germany's chancellor and over the next few months he banned opposition political parties, free speech, independent cultural organizations and universities and the rule of law. Anti-Semitism became government policy and German Jews, including the psychologists, Erich Fromm, Max Eitingon and Ernst Simmel, left the country. Sigmund Freud wrote to his nephew in Manchester that "life in Germany has become impossible." (49)

On 10th May, 1933, the Nazi Party arranged the burning of thousands of "degenerate literary works" were burnt in German cities. This included books by people such as Sigmund Freud, Rosa Luxemburg, August Bebel, Eduard Bernstein, Heinrich Mann, Bertolt Brecht, Helen Keller, H.G. Wells, Ernest Hemingway, Sinclair Lewis, Otto Dix, Victor Hugo, Lenin, Leon Trotsky, Hans Eisler, Ernst Toller, Albert Einstein, D.H. Lawrence, John Dos Passos, Theodore Dreiser, Karl Kautsky, Thomas Heine, Arnold Zweig, Ludwig Renn, Rainer Maria Rilke, Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, George Grosz, Maxim Gorky and Isaac Babel. (50)

In June 1933 the German Society for Psychotherapy (GSP) came under the control of the Nazi Party. It was now led by Matthias Göring, a cousin of Hermann Göring, and a leading member of Hitler's government. Matthias Göring told all members that they were expected to make a thorough study of Mein Kampf, which was to serve as the basis for their work. Ernst Kretschmer, the president of the GSP, promptly resigned and was replaced by Carl Jung. He justified his continued collaboration with the Nazis on grounds of expediency. (51)

As leader of the German Society for Psychotherapy, Jung assumed overall responsibility for its publication, the Zentralblatt für Psychotherapie. In 1933, this journal published a statement endorsing Nazi positions and Hitler's book Mein Kampf. Jung defended himself by claiming that "the main point is to get a young and insecure science into a place of safety during an earthquake". (52) However, Geoffrey Cocks, the author of Psychotherapy in the Third Reich (1985) argues that with this appointment, Jung's ideas had "official approval" and, as a result, "German psychotherapists did all they could to link Jung's name with their own activities". (53)

Jung claimed that he took this post expressly to defend the rights of Jewish psychotherapists, and he altered the constitution of the GSP so that it became a fully and formally international body. Membership was by means of national societies with a special category of individual membership. In this way he overcame the problem of Jews being banned from the organisation. However, it has been pointed out: "To put this in context, it should be noted that Freud's books had been burnt, and he was officially banned in 1933." (54)

Carl Jung upset many people in an article, The State of Psychotherapy Today (1934) in which he made an attempt to defend fascism in an attack on Jewish psychologists such as Sigmund Freud and Alfred Adler: "Freud did not understand the Germanic psyche any more than did his Germanic followers. Has the formidable phenomenon of National Socialism, on which the whole world gazes with astonishment, taught them better? Where was that unparalleled tension and energy while as yet no National Socialism existed? Deep in the Germanic psyche, in a pit that is anything but a garbage-bin of unrealizable infantile wishes and unresolved family resentments."

Jung then went on to compare Aryans and Jews: "The 'Aryan' unconscious has a higher potential than the Jewish.... The Jew who is something of a nomad has never yet created a cultural form of his own and as far as we can see never will, since all his instincts and talents require a more or less civilized nation to act as host for their development. The Jews have this peculiarity with women; being physically weaker, they have to aim at the chinks in the armour of their adversary." (55)

In the Zentralblatt für Psychotherapie Jung wrote that "the differences which actually do exist between Germanic and Jewish psychology and which have been long known to every intelligent person are no longer to be glossed over." (56) In a letter to his pupil Dr Kranefeldt in 1934, Jung wrote: "As is known, one cannot do anything against stupidity, but in this instance the Aryan people can point out that, with Freud and Adler, specifically Jewish points of view are publicly preached, and as can be proved likewise, points of view that have an essentially corrosive character. If the proclamation of this Jewish gospel is agreeable to the government, then so be it. Otherwise there is also the possibility that this would not be agreeable to the government. (57)

In 1938 Carl Jung gave an interview that was not published until four years later. Jung compared the German worship of Adolf Hitler to the Jewish desire for a Messiah, a "characteristic of people with an inferiority complex." He describes Hitler’s power as a form of "magic", but that power only exists, he says, because "Hitler listens and obeys... the true leader is always led. His Voice is nothing other than his own unconscious, into which the German people have projected their own selves; that is, the unconscious of seventy-eight million Germans. That is what makes him powerful. Without the German people he would be nothing."

Jung then went on to compare the fascists in Germany with the Jews. "It seems that the German people are now convinced they have found their Messiah. In a way the position of the Germans is remarkably like that of Jews of old. Since their defeat in the world war the Germans have awaited a Messiah, a Saviour. That is characteristic of people with an inferiority complex. The Jews got their inferiority complex from geographical and political factors." (58)

Andrew Samuels has made a detailed assessment of the ideas of Adolf Hitler and Carl Jung. "Hitler regarded all history as consisting of struggles between competing nations for living space and, eventually, for world domination. The Jews, according to Hitler, are a nation and participate in these struggles, but their goal, quite directly and in the first instance, is world domination. This is because the Jews do not start off with possession of living space, of an identifiable, geographical locality; it has to be the world or nothing.... The Jewish nation achieves its goal of world domination by denationalizing existing states from within and imposing a homogeneous "Jewish" character on them by its international capitalism and its equally international communism. So, in Hitler's thinking, there is a struggle between wholesome nationhood and its corrupting; enemy, the Jews."

Samuels then goes on to argue: "Jung, too, was interested in the idea of the nation, and he makes innumerable references to 'the psychology of the nation' and to the influence of a person's national background. He says that 'the soil of every country holds a mystery.... There is a relationship of body to earth.' For example in 1918, Jung asserted that the skull and pelvis measurements of second-generation American immigrants were becoming 'indianized'. It can be seen that even in such craziness, Jung was not thinking along racial lines, for the immigrants from Europe and the indigenous Indians come from different races. No, living in America, living on American soil, being part of the American nation, these are what exert profound physiological and psychological effects. 'The foreign land... has

assimilated the conqueror,' says Jung, and his argument is not based on race but on earth and culture as the matrix from which we evolve. Earth plus culture equals nation."

Samuels suggests that Jung gave support to Hitler's nationalism: "It is my contention that, in C.G. Jung, nationalism found its psychologist. But in his role as a psychologist of nationhood, his role as a psychologist who lends his authority to nationalism, Jung's pan-psychism (his phrase) ran riot. This refers to the tendency to see all outer events in terms of inner dynamics, and it led Jung to claim that the nation is a personified concept that corresponds in reality only to a specific nuance of the individual psyche... The nation is nothing but an inborn character... Thus in many ways it is an advantage to have been imprinted with the English national character in one's cradle."

Samuels concludes: "First, a crucial aspect of Hitler's thinking is that the Jews represent a threat to the inevitable and healthy struggle of different nations for world domination. Second, Jung's view is that each nation has a different and identifiable national psychology that is, in some mysterious manner, an innate factor. At first sight, juxtaposing these two points of view might seem innocuous, or pointless, or even distasteful in itself. It is certainly not my intention to make a straightforward comparison of Hitler and Jung. But if we go on to explore the place of the Jews in Jung's mental ecology, to find out where they are situated in his view of the world, then the juxtaposition of the two points of view takes on a far more profound significance... My perception is that the ideas of nation and of national difference form a fulcrum between the Hitlerian phenomenon and Jung's analytical psychology. For, as a psychologist of nations, Jung too would feel threatened by the Jews, this strange so-called nation without a land. Jung, too, would feel threatened by the Jews, this strange nation without cultural forms - that is, without national cultural forms - of its own, and hence, in Jung's words of 1933, requiring a 'host nation'... Jung argues that everybody is affected by their background and this leads to all kinds of prejudices and assumptions." (59)

Carl Jung later defended his work for the German Society for Psychotherapy by the claim that he concentrated on the international division of the society and that he used this position to "he was actually fighting to keep German psychotherapy open to Jewish individuals". He also argued that Matthias Göring put Jung's name to pro-Nazi statements without his knowledge. (60)

Jung told the journalist, Hubert R. Knickerbocker, in January 1939: "There is no question but that Hitler belongs in the category of the truly mystic medicine man. As somebody commented about him at the last Nuremburg party congress, since the time of Mohammed nothing like it has been seen in this world. His body does not suggest strength. The outstanding characteristic of his physiognomy is its dreamy look. I was especially struck by that when I saw pictures taken of him in the Czechoslovakian crisis; there was in his eyes the look of a seer. This markedly mystic characteristic of Hitler's is what makes him do things which seem to us illogical, inexplicable, and unreasonable. ... So you see, Hitler is a medicine man, a spiritual vessel, a demi-deity or, even better, a myth." (61)

Final Years

It was not until just before the Second World War that he resigned as president of the German Society for Psychotherapy. After the war he told Carol Baumann: "It must be clear to anyone who has read any of my books that I have never been a Nazi sympathizer and I never have been anti-Semitic, and no amount of misquotation, mistranslation, or rearrangement of what I have written can alter the record of my true point of view. Nearly every one of these passages has been tampered with, either by malice or by ignorance. Furthermore, my friendly relations with a large group of Jewish colleagues and patients over a period of many years in itself disproves the charge of anti-Semitism." (62)

Other books by Jung include Psychology and Religion (1937), The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious (1939), Paracelsus the Physician (1942), Psychology and Alchemy (1944), Aion (1951), The Undiscovered Self (1957) and an autobiography, Memories, Dreams, Reflections (1962).

Carl Jung died at Küsnacht on 6th June 1961.

Primary Sources

(1) Carl Jung, The Psychology of Individuation (1921)

We should not pretend to understand the world only by the intellect; we apprehend it just as much by feeling. Therefore, the judgment of the intellect is, at best, only the half of truth, and must, if it be honest, also come to an understanding of its inadequacy.

(2) Carl Jung, Women In Europe (1927)

It is a woman's outstanding characteristic that she can do anything for the love of a man. But those women who can achieve something important for the love of a thing are most exceptional, because this does not really agree with their nature. Love for a thing is a man's prerogative. But since masculine and feminine elements are united in our human nature, a man can live in the feminine part of himself, I and a woman in her masculine part. None the less the feminine element in man is only something in the background, as is the masculine element in woman. If one lives out the opposite sex in oneself one is living in one's own background, and one's real individuality suffers. A man should live as a man and a woman as a woman.

(3) Carl Jung, The State of Psychotherapy Today (1934)

Freud did not understand the Germanic psyche any more than did his Germanic followers. Has the formidable phenomenon of National Socialism, on which the whole world gazes with astonishment, taught them better? Where was that unparalleled tension and energy while as yet no National Socialism existed? Deep in the Germanic psyche, in a pit that is anything but a garbage-bin of unrealizable infantile wishes and unresolved family resentments.

The 'Aryan' unconscious has a higher potential than the Jewish.... The Jew who is something of a nomad has never yet created a cultural form of his own and as far as we can see never will, since all his instincts and talents require a more or less civilized nation to act as host for their development. The Jews have this peculiarity with women; being physically weaker, they have to aim at the chinks in the armour of their adversary.

(4) Carl Jung, The Integration of the Personality (1939)

If there is anything that we wish to change in the child, we should first examine it and see whether it is not something that could better be changed in ourselves.

(5) Carl Jung, interviewed by Hubert R. Knickerbocker, Cosmopolitan Magazine (January 1939)

There is no question but that Hitler belongs in the category of the truly mystic medicine man. As somebody commented about him at the last Nuremberg party congress, since the time of Mohammed nothing like it has been seen in this world. His body does not suggest strength. The outstanding characteristic of his physiognomy is its dreamy look. I was especially struck by that when I saw pictures taken of him in the Czechoslovakian crisis; there was in his eyes the look of a seer. This markedly mystic characteristic of Hitler's is what makes him do things which seem to us illogical, inexplicable, and unreasonable.... So you see, Hitler is a medicine man, a spiritual vessel, a demi-deity or, even better, a myth.

(6) Carl Jung, The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious (1939)

The over development of the maternal instinct is identical with that well-known image of the mother which has been glorified in all ages and all tongues. This is the mother love which is one of the most moving and unforgettable memories of our lives, the mysterious root of all growth and change; the love that means homecoming, shelter, and the long silence from which everything begins and in which everything ends. Intimately known and yet strange like Nature, lovingly tender and yet cruel like fate, joyous and untiring giver of life-mater dolorosa and mute implacable portal that closes upon the dead. Mother is mother love, my experience and my secret. Why risk saying too much, too much that is false and inadequate and beside the point, about that human being who was our mother, the accidental carrier of that great experience which includes herself and myself and all mankind, and indeed the whole of created nature, the experience of life whose children we are? The attempt to say these things has always been made, and probably always will be; but a sensitive person cannot in all fairness load that enormous burden of meaning, responsibility, duty, heaven and hell, on to the shoulders of one frail and fallible human being-so deserving of love, indulgence, understanding, and forgiveness-who was our mother. He knows that the mother carries for us that inborn image of the mater nature and mater spiritualis, of the totality of life of which we are a small and helpless part.

(7) Carl Jung, The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious (1939)

The woman who fights against her father still has the possibility of leading an instinctive, feminine existence, because she rejects only what is alien to her. But when she fights against the mother she may, at the risk of injury to her instincts, attain to greater consciousness, because in repudiating the mother she repudiates all that is obscure, instinctive, ambiguous, and unconscious in her own nature.

(8) Carl Jung, Paracelsus the Physician (1942)

No one can flatter himself that he is immune to the spirit of his own epoch, or even that he possesses a full understanding of it. Irrespective of our conscious convictions, each one of us, without exception, being a particle of the general mass, is somewhere attached to, colored by, or even undermined by the spirit which goes through the mass. Freedom stretches only as far as the limits of our consciousness.

Student Activities

Adolf Hitler's Early Life (Answer Commentary)

The Assassination of Reinhard Heydrich (Answer Commentary)

Heinrich Himmler and the SS (Answer Commentary)

The Last Days of Adolf Hitler (Answer Commentary)

Trade Unions in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler v John Heartfield (Answer Commentary)

Hitler's Volkswagen (The People's Car) (Answer Commentary)

Women in Nazi Germany (Answer Commentary)

German League of Girls (Answer Commentary)

Kristallnacht (Answer Commentary)

The Political Development of Sophie Scholl (Answer Commentary)

The White Rose Anti-Nazi Group (Answer Commentary)

The Hitler Youth (Answer Commentary)

Night of the Long Knives (Answer Commentary)

British Newspapers and Adolf Hitler (Answer Commentary)

An Assessment of the Nazi-Soviet Pact (Answer Commentary)

Lord Rothermere, Daily Mail and Adolf Hitler (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler and the Beer Hall Putsch (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler and the German Workers' Party (Answer Commentary)

Adolf Hitler the Orator (Answer Commentary)

Sturmabteilung (SA) (Answer Commentary)