Civilian Conservation Corps

After he was elected President Franklin D. Roosevelt initially opposed massive public works spending. However, by the spring of 1933, the needs of more than fifteen million unemployed had overwhelmed the resources of local governments. In some areas, as many as 90 per cent of the people were on relief and it was clear something needed to be done. His close advisors and colleagues, Harry Hopkins, Rexford Tugwell, Robert LaFollette Jr. Robert Wagner, Fiorello LaGuardia, George Norris and Edward Costigan eventually won him over. (1)

Frances Perkins explained in her book, The Roosevelt I Knew (1946): In one of my conversations with the President in March 1933, he brought up the idea that became the Civilian Conservation Corps. Roosevelt loved trees and hated to see them cut and not replaced. It was natural for him to wish to put large numbers of the unemployed to repairing such devastation. His enthusiasm for this project, which was really all his own, led him to some exaggeration of what could be accomplished. He saw it big. He thought any man or boy would rejoice to leave the city and work in the woods. It was characteristic of him that he conceived the project, boldly rushed it through, and happily left it to others to worry about the details." (2)

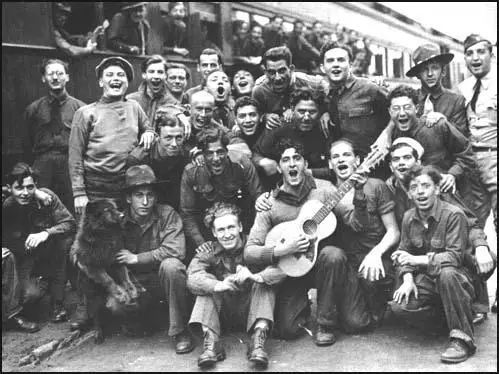

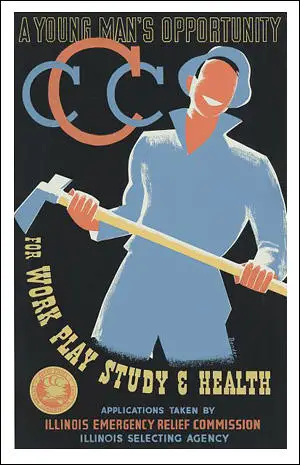

On 21st March, 1933, sent an unemployment relief message to Congress. It took only eight days to create the Civilian Conservation Corps. It authorized half a billion dollars in direct federal grants to the states for relief. The CCC was a program designed to tackle the problem of unemployed young men aged between 18 and 25 years old. By September, 1935, over five hundred thousand young men lived in CCC camps. (3)

The CCC camps were set up all over the United States. Blackie Gold told Studs Terkel: "I was at CCC's for six months, I came home for fifteen days, looked around for work, and I couldn't make $30 a month, so I enlisted back in the CCC's and went to Michigan. I spent another six months there planting trees and building forests. And came out. But still no money to be made. So back in the CCC's again. From there I went to Boise, Idaho, and was attached to the forest rangers. Spent four and a half hours fighting forest fires." (4)

The organisation was based on the armed forces with officers in charge of the men. Over 25,000 men were First World War veterans. The pay was $30 dollars a month with $22 dollars of it being sent home to dependents. The men planted three billion trees, built public parks, drained swamps to fight malaria, built a million miles of roads and forest trails, restocked rivers with nearly a billion fish, worked on flood control projects and a range of other work that helped to conserve the environment. Between 1933 and 1941 over 3,000,000 men served in the CCC. (5)

Primary Sources

(1) Frances Perkins was secretary for labour in Franklin D. Roosevelt's first cabinet. She wrote about this period in her book, The Roosevelt I Knew (1946)

In one of my conversations with the President in March 1933, he brought up the idea that became the Civilian Conservation Corps. Roosevelt loved trees and hated to see them cut and not replaced. It was natural for him to wish to put large numbers of the unemployed to repairing such devastation. His enthusiasm for this project, which was really all his own, led him to some exaggeration of what could be accomplished. He saw it big. He thought any man or boy would rejoice to leave the city and work in the woods.

It was characteristic of him that he conceived the project, boldly rushed it through, and happily left it to others to worry about the details. And there were some difficult details. The attitude of the trade unions had to be considered. They were disturbed about this program, which they feared would put all workers under a "dollar a day" regimentation merely because they were unemployed.

(2) Rexford Tugwell was an assistant secretary in the Agricultural Department in 1933. He wrote about his experiences in The Democratic Roosevelt (1957)

During the late spring the Civilian Conservation Corps got underway with some awkwardness. What had begun as a simple notion that the experienced foresters would take under their care and direction a certain number of idle young men turned out in practice to be not so simple. There were problems of recruiting; who was to be chosen? There were problems of housing; who was to build the camps? It was finally decided that all those sent to camps should come from families on relief. It was also decided, when pacifying the unions had become something of an issue, that the boys would not build their own camps but that union labour would do it.

(3) The journalist, James D. Horan, wrote about the Civilian Conservation Corps in his book, The Desperate Years (1962)

The Civilian Conservation Corps became the most popular of all the New Deal agencies. Jobless youths working in the outdoors, teenagers building roads in the unpenetrated sections of the Far West - the prospect caught the public imagination. It also impressed business men. They later showed a preference for hiring a man who had been in the CCC, and the reasoning was simple: employers felt that anyone who had been in the CCC would know what a full day's work meant and how to carry out orders in a disciplined way.

I vividly recall covering the first day of enrollment at army headquarters in downtown New York when the first applicants arrived. Most of them, in thin summer clothes with no overcoats, had lined up before dawn. The first boy accepted was from the lower East Side. He was dancing a jig to celebrate when reporters told him he would probably be sent to the West. He stopped jigging and a newsman asked if anything was wrong. The boy scratched his head and said very seriously, "What the hell are we going to do about those Indians?"

(4) Blackie Gold, who joined the CCC in 1937, was interviewed by Studs Terkel in Hard Times (1970)

I was at CCC's for six months, I came home for fifteen days, looked around for work, and I couldn't make $30 a month, so I enlisted back in the CCC's and went to Michigan. I spent another six months there planting trees and building forests. And came out. But still no money to be made. So back in the CCC's again. From there I went to Boise, Idaho, and was attached to the forest rangers. Spent four and a half hours fighting forest fires...

I really enjoyed it. I had three wonderful square meals a day. No matter what they put on the table, we ate and were glad to get it. Nobody ever turned down food. They sure made a man out of ya, because you learned that everybody here was equal. There was nobody better than another in the CCC's.

Student Activities

Economic Prosperity in the United States: 1919-1929 (Answer Commentary)

Women in the United States in the 1920s (Answer Commentary)

Volstead Act and Prohibition (Answer Commentary)

The Ku Klux Klan (Answer Commentary)

Classroom Activities by Subject