Britain: 1918-1924

Two weeks after the end of the war, the prime minister, David Lloyd George gave a speech in Wolverhampton: "‘The work is not over yet – the work of the nation, the work of the people, the work of those who have sacrificed. Let us work together first. What is our task? To make Britain a fit country for heroes to live in. I am not using the word ‘heroes’ in any spirit of boastfulness, but in the spirit of humble recognition of fact. I cannot think what these men have gone through. I have been there at the door of the furnace and witnessed it, but that is not being in it, and I saw them march into the furnace. There are millions of men who will come back. Let us make this a land fit for such men to live in. There is no time to lose. I want us to take advantage of this new spirit. Don’t let us waste this victory merely in ringing joybells." (1)

The 1919-1922 government of David Lloyd George was mainly made up of members of the Conservative Party. However, he did appoint a former Liberal Party member, Christopher Addison, as president of the Local Government Board, with the responsibility of fulfilling the government's pledges of post-war reform. Before entering politics he was a doctor at Charing Cross Hospital, where he developed a lifelong concern with health and social deprivation in London's East End. (2)

The other reformer in his government was Herbert Fisher, who had been appointed as President of the Board of Education in 1916. Fisher, a historian, had strong views on education and was determined to improve the quality of teaching in British schools: "The young should not be trusted to the care of sad, melancholy, careworn teachers. The classroom should be a cheerful place." In an attempt to attract good teachers he doubled their pay and tripled the pension of every elementary school teacher. (3)

Fisher also guided the 1918 Education Act through Parliament in the last months of the First World War. To ensure that "children and young persons shall not be debarred from receiving the benefits of any form of education by which they are capable of profiting through inability to pay." This made attendance at school compulsory for children up to the age of 14 and gave permission to local education authorities to extend it to fifteen. Other features of the legalization included the provision of ancillary services (medical inspection, nursery schools, centres for pupils with special needs, etc.) "Fisher represented the progressive spirit which characterised Lloyd George before December, 1916." (4)

Fisher always saw the best in Lloyd George who gave him great freedom as President of the Board of Education. "His animated courage and buoyancy of temper... his easy power of confident decision in the most perilous of emergencies injected a spirit of cheerfulness and courage which was of extraordinary value during those anxious years... During the war he was at the summit of his brilliant powers." (5)

David Lloyd George: 1918-1920

David Lloyd George argued during the campaign that he was the "man who won the war" and he was "going to make Britain a fit country for heroes to live in." One measure that helped him to do this was increasing the number of people protected against unemployment to 8 million workers who had not been covered by the 1911 National Insurance Act. This now included people earning less than £250 a year. The rate of male benefit was increased from fifteen to twenty shillings a week to ensure that unemployed ex-servicemen were not disadvantaged when they moved from the demobilisation 'dole' to the national scheme. (6)

The main problem facing the government was the housing crisis. After the war more than 400,000 houses - the homes of 1.5 million men, women and children - had been condemned as unfit for human habitation. Christopher Addison introduced the Housing and Town Planning Act which launched a massive new programme of house building by the local authorities. This included a government subsidy to cover the difference between the capital costs and the income earned through rents from working-class tenants.

The government promised to make sure that 100,000 new houses were built and that another 200,000 would follow as soon as land could be obtained. Kenneth O. Morgan has argued: "Controversy dogged the housing programme from the start. Progress in house building was slow, the private enterprise building industry was fragmented, the building unions were reluctant to admit unskilled workers, the local authorities could hardly cope with their massive new responsibilities, and Treasury policy overall was unhelpful. In addition, the costs of the Treasury subsidy began to soar, with uncontrolled prices of raw materials leading to apparently open-ended subventions from the state." (7)

The targets were never realised, although between 1919 and 1922, 213,000 low-cost houses were completed. Over 170,000 of them were built by local authorities and partly financed by government subsidies. Austen Chamberlain, the Chancellor of the Exchequer told the Cabinet Finance Committee that every house built under government sponsorship cost the Treasury between £50 and £75 a year and would continue to do so for the next sixty years. In March 1921, Addison was replaced by the more conservative, Sir Arthur Mond. (8)

David Lloyd George lost his radical instincts in the post-war government. George Riddell wrote in his diary: "I notice that Lloyd George is steadily veering over to the Tory point of view... He says one Leverhulme (soap manufacturer) or Ellerman (shipping magnate) is worth more to the world than 10,000 sea captains or 20,000 engine drivers and should be remunerated accordingly... He wants to improve the world and the condition of the people but he wants to do it in his own way." (9)

After the war the ending of price controls, prices rose twice as fast during 1919 as they had done during the worst years of the war. That year 35 million working days were lost to strikes, and on average every day there were 100,000 workers on strike - this was six times the 1918 rate. There were stoppages in the coal mines, in the printing industry, among transport workers, and the cotton industry. There were also mutinies in the military and two separate police strikes in London and Liverpool. (10)

The miners were encouraged to go back to work by the government agreeing to establish a royal commission under John Sankey, a high court judge. Others on the commission included trade unionists, Robert Smillie, Herbert Smith and Frank Hodges. Other progressive figures such as R. H. Tawney, Sidney Webb and Leo Chiozza Money, were also included, but Arthur Balfour, and several conservative businessmen meant that they could not publish a united report.

In June 1919 the Sankey Commission came up with four reports, which ranged from complete nationalization on the part of the workers' representatives to restoration of undiluted private ownership on that of the owners. On 18th August, Lloyd George used the excuse of this disagreement to reject nationalization but offered the prospect of reorganization. When this was rejected by the Miners' Federation of Great Britain, the government kept control of the industry. It also agreed to pass legislation that would guarantee the miners a seven-hour day. (11)

The government lost a series of by-elections. Herbert Fisher proposed several radical measures that would be popular with the public. This included votes for women over the age of twenty-one, proportional representation and social welfare legislation. Lloyd George rejected the proposal and was more concerned with measures to deal with the growing socialist movement. He claimed that "unless there is is a concerted effort made to arrest this tendency, very grave consequences may ensure for the whole country." (12)

In 1920 David Lloyd George became convinced that Britain was on the verge of revolution that he was determined to suppress it. After inquiring about the number of troops available to him he asked Sir Hugh Trenchard, Chief of the Air Staff: "How many airman are available for the revolution? Trenchard replied that there were 20,000 mechanics and 2,000 pilots, but only a hundred machines which could be kept going in the air... The pilots had no weapons for ground fighting. The PM presumed they could use machine guns and drop bombs." (13)

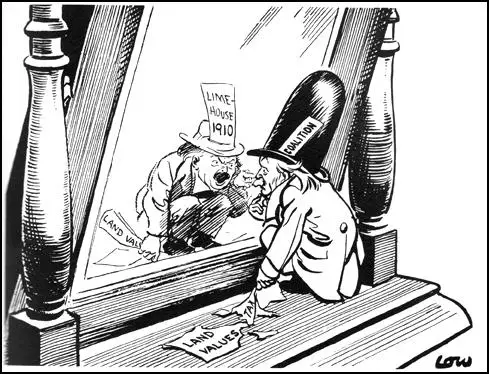

Lloyd George's reactionary policies came under attack from former supporters. This included David Low who attacked him for betraying his radical past. In one cartoon, Reflections, he refered to a speech he had made on 30th July 1909 at Limehouse in the East End of London, where "he had bitterly attacked dukes, landlords, capitalists - the whole of the upper classes". Lloyd George welcomed the criticism as it helped to inform the public that it was the Conservative Party that was blocking his reform measures. (13a)

Low disagreed and suggested he helped bring him down: "David Lloyd George was the best-hated statesman of his time, as well as the best loved. The former I have good reason to know; every time I made a pointed cartoon against him, it brought batches of approving letters from all the haters. Looking at Lloyd George's pink and hilarious, head thrown back, generous mouth open to its fullest extent, shouting with laughter at one of his own jokes, I thought I could see how it was that his haters hated him... I always had the greatest difficulty in making Lloyd George sinister in a cartoon. Every time I drew him, however critical the comment, I had to be careful or he would spring off the drawing-board a lovable cherubic little chap. I found the only effective way of putting him definitely in the wrong in a cartoon was by misplacing this quality in sardonic incongruity - by surrounding the comedian with tragedy." (13b)

In January 1921, Arthur J. Cook, the left-wing militant from South Wales became a member of the executive of the Miners' Federation of Great Britain (MFGB). "A month later the decontrol of the mining industry was announced, with a consequent end to a national wages agreement and wage reductions. A three-month lock-out from April 1921 ended in defeat for the miners; at its end Cook was again gaoled for two months' hard labour for incitement and unlawful assembly". (14)

Will Paynter, later recorded: "Cook had been a union leader at the colliery next down the valley to where I worked and we heard much of his exploits there as a fighter for wages and particularly for pit safety... He was... a master of his craft on the platform. I attended many of his meetings when he came to the Rhondda and he was undoubtedly a great orator, and had terrific support throughout the coalfields." (15) During this period he developed a reputation as a great orator. John Sankey, a High Court Judge, once stood at the back of a crowded miners' meeting to hear Cook speak. "Within fifteen minutes half the audience was in tears and Sankey admitted to having the greatest difficulty in restraining himself from weeping." (16)

In August, 1921, Lloyd George appointed Eric Geddes, was made chairman of a committee, largely made up of businessmen - which was to devise ways of cutting public expenditure. The committee recommended public expenditure cuts of £86 million, later reduced to £64 million. He also suggested that the standard rate of income tax was reduced from 6/- to 5/- in the pound. The cuts in the education budget that amounted to an increase in minimum class sizes. "He was sure that the brighter children would learn as readily and as quickly in a class of seventy as they would in a much smaller class." (17)

Irish Home Rule

Lloyd George also had to deal with the problem of Ireland. In the 1918 General Election, the republican party, Sinn Féin, won a landslide victory in Ireland. On 21st January 1919 they formed a breakaway government (Dáil Éireann) and declared independence from Britain. Later that day, two members of the British-organised armed police force, the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC), were shot dead in County Tipperary while escorting a lorry load of dynamite to a quarry. "From then on, violence escalated week by week. Often the police - many of whom preferred retaliation and reprisals to prosecutions - were as guilty as the recently formed Irish Republican Army." (18)

The Daily Chronicle, a newspaper under the control of Lloyd George, commented: "It is obvious that if those murderers pursue their course much longer, we may see counter clubs spring up and the life of prominent Sinn Feiners becoming as unsafe as the prominent officers." The predicted counter-attack began on 20th March 1920, with the murder of Tomás MacCurtain, the moderate Sinn Fein mayor of Cork, was shot dead on his 36th birthday, in front of his wife and children. The jury of the coroner's court, which included Unionists - came to the unanimous conclusion that the "wilful murder was organized and carried out by the Royal Irish Constabulary officially directed by the British Government." (19)

An estimated 10% of the Royal Irish Constabulary resigned between August 1918 and August 1920. Winston Churchill, the Secretary of State for War, suggested that that the government should recruit British ex-servicemen to serve as policemen in Ireland. Over the next few weeks 4,400 men, who received the good wage of 10 shillings a day, joined the Royal Irish Constabulary Special Reserve. They obtained the nickname, Black and Tans, from the colours of the improvised uniforms they initially wore, composed of mixed khaki British Army and rifle green RIC uniform parts. (20)

Complaints were soon received about the behaviour of the Black and Tans and the government was attacked in the House of Commons by the Labour Party for using terror tactics. David Lloyd George rejected these claims in a speech where he denounced the insurgency as "organized assassination of the most cowardly kind" but assured his audience, that "we have murder by the throat". (21)

The Cairo Gang was a group of British intelligence agents who were sent to Dublin with the intention of assassinating leading members of the IRA. Unfortunately, the IRA had a spy in the ranks of the RIC and twelve members of this group, were killed on the morning of 21st November 1920 in a planned series of simultaneous early-morning strikes engineered by Michael Collins. The men killed included Colonel Wilfrid Woodcock, Lieutenant-Colonel Hugh Montgomery, Major Charles Dowling, Captain George Bennett, Captain Leonard Price, Captain Brian Keenlyside, Captain William Newberry, Lieutenant Donald MacLean, Lieutenant Peter Ames, Lieutenant Henry Angliss and Lieutenant Leonard Wilde. (22)

That afternoon the Royal Irish Constabulary drove in trucks into Croke Park during a football match, shooting into the crowd. Fourteen civilians were killed, including one of the players, Michael Hogan, and a further 65 people were wounded. Later that day two republicans, Richard McKee, Peadar Clancy and an unassociated friend, Conor Clune were arrested and after being tortured were shot dead "while trying to escape". (23)

It was claimed that during his training a member of the Black and Tans was told to shout "Hands up" at civilians, and to shoot anyone who did not immediately obey. He added: "Innocent persons may be shot, but that cannot be helped, and you are bound to get the right parties some time. The more you shoot, the better I will like you, and I assure you no policeman will get into trouble for shooting any man." General Frank Crozier, who was the commander of the Black and Tans, resigned in 1921 because they had been "used to murder, rob, loot, and burn up the innocent because they could not catch the few guilty on the run". (24)

Winston Churchill argued that the government should endorse a policy change that involved "the substitution of regular, authorized and legalized reprisals for unauthorized reprisals by police and soldiers". Lloyd George rejected this idea but refused to condemn the brutality of the Black and Tans because he thought it was the only way to reduce attacks upon the police and the army. C. P. Scott, the editor of the Manchester Guardian, was disappointed by this response and he ended his twenty-one year friendship with Lloyd George. (25)

On 20th July, 1921, the Cabinet agreed to accept Lloyd George's plan to solve the conflict in Ireland. Twenty-six counties were to be offered dominion status, whereas the six counties in the north would remain part of the Union. At first Sinn Fein rejected the proposals but on 6th December, at talks with the government, the republican delegation signed the treaty. Michael Collins, the leader of the IRA, wrote in his diary, "I tell you this, early this morning I signed my death warrant." (Collins was in fact assassinated by anti-treaty members of the IRA on 22nd August 1922). (26)

Roy Hattersley claims the peace treaty was an example of Lloyd George's negotiating technique, "a combination of charm, ruthless determination, ingenuity and, when necessary, dishonesty". He had succeeded in obtaining a settlement where William Pitt, Robert Peel and William Gladstone had failed. "They had struggled to achieve what they thought right. He had achieved what he judged to be possible." (27)

Lloyd George gradually lost the support of his Cabinet colleagues. After Edwin Montagu resigned in March 1922, he criticised the style of Lloyd George's leadership: "We have been governed by a great genius - a dictator who has called together from time to time conferences of Ministers, men who had access to him day and night, leaving all those who, like myself, found it impossible to get him for days together. He has come to epoch-making decisions, over and over again. It is notorious that members of the Cabinet had no knowledge of those decisions." (28)

Selling Honours Scandal

Lloyd George was aware that he would have to fight the next election without the support of the Conservative Party. It was claimed that Lloyd George was guilty of selling honours. Since the beginning of the eighteenth century honours had been distributed out of gratitude for political donations. However, critics pointed out that on Lloyd George's recommendation, the King had created 294 new nights in 18 months and 99 new hereditary peers in six years - twice the annual rate of any other period in history. (29)

Alan Percy, 8th Duke of Northumberland, had been an opponent of Lloyd George since he had attacked his father, Henry Percy, 7th Duke of Northumberland, for exploiting land values. Northumberland held extreme right-wing views who financed and directed The Patriot, a weekly newspaper which published Nesta Webster and promoted a mix of anti-communism and anti-semitism. Webster argued that communism was a Jewish conspiracy. (30)

On 17th July, 1922, Northumberland made a speech attacking the way Lloyd George had been selling honours: "The Prime Minister's party, insignificant in numbers and absolutely penniless four years ago, has, in the course of those four years, amassed an enormous party chest, variously estimated at anything from one to two million pounds. The strange thing about it is that this money has been acquired during a period when there has been a more wholesale distribution of honours than ever before, when less care has been taken with regard to the service of the recipients than ever before and when whole groups of newspapers have been deprived of real independence by the sale of honours and constitute a mere echo of Downing Street from where they are controlled."

Northumberland read out from a letter that suggested that you could obtain a knighthood for £12,000 and a baronetcy for £35,000. "There are only five knighthoods left for the June list. If you decide on a baronetcy, you may have to wait for the Retiring List ... It is not likely that the next government will give so many honours and this is an exceptional opportunity." The letter ended with the comment: "It is unfortunate that Governments must have money, but the party now in power will have to fight Labour and Socialism, which will be an expensive matter." (31)

Northumberland argued that Lloyd George had used the honours system to encourage the newspapers not to criticise him. Lloyd George had in fact ennobled six proprietors during the last few years. Over a period of time the Conservative Party had given honours to all the important press lords. This included Alfred Harmsworth, Lord Northcliffe (The Daily Mail and The Times), Harold Harmsworth, Lord Rothermere (The Daily Mirror), Harry Levy-Lawson, Lord Burnham (The Daily Telegraph) and William Maxwell Aitken, Lord Beaverbrook (The Daily Express). As a result, their newspapers continued to criticise Lloyd George. (32)

David Lloyd George responded to the charges made by the Duke of Northumberland by admitting that: "As to the question of bargain and sale, I agree with everything that has been said about that. If it ever existed, it was a discreditable system. It ought never to have existed. If it does exist, it ought to be terminated, and if there were any doubt on that point, every step should be taken to deal with it." But he insisted that making donations to a political party should not exclude the receipt of an honour which was justified if they had been involved in "good works". He announced the setting up of a Royal Commission with a remit to recommend how the honours system could be "insulated from even the suggestion of corruption". (33)

The following month Lloyd George had to defend himself from the charge of profiteering from the First World War when The Evening Standard revealed that a United States publisher had offered £90,000 for the American rights to his memoirs. (34) It was claimed that he was going to make a fortune out of a conflict in which so many men had died. The public outcry far exceeded the expressions of distaste which were provoked by the honours scandal. After two weeks of hostile newspaper articles, Lloyd George made a statement that the money would be "devoted to charities connected with the relief of suffering caused by the war." (35)

At a meeting on 14th October, 1922, two younger members of the government, Stanley Baldwin and Leo Amery, urged the Conservative Party to remove Lloyd George from power. Andrew Bonar Law disagreed as he believed that he should remain loyal to the Prime Minister. In the next few days Bonar Law was visited by a series of influential Tories - all of whom pleaded with him to break with Lloyd George. This message was reinforced by the result of the Newport by-election where the independent Conservative won with a majority of 2,000, the coalition Conservative came in a bad third.

Another meeting took place on 18th October. Austen Chamberlain and Arthur Balfour both defended the coalition. However, it was a passionate speech by Baldwin: "The Prime Minister was described this morning in The Times, in the words of a distinguished aristocrat, as a live wire. He was described to me and others in more stately language by the Lord Chancellor as a dynamic force. I accept those words. He is a dynamic force and it is from that very fact that our troubles, in our opinion, arise. A dynamic force is a terrible thing. It may crush you but it is not necessarily right." The motion to withdraw from the coalition was carried by 187 votes to 87. (36)

David Lloyd George was forced to resign and his party only won 127 seats in the 1922 General Election. The Conservative Party won 344 seats and formed the next government. The Labour Party promised to nationalise the mines and railways, a massive house building programme and to revise the peace treaties, went from 57 to 142 seats, whereas the Liberal Party increased their vote and went from 36 to 62 seats. (37)

Lloyd George was never to hold office again. A. J. P. Taylor wrote: "He (David Lloyd George was the most inspired and creative British statesman of the twentieth century. But he had fatal flaws. He was devious and unscrupulous in his methods. He aroused every feeling except trust. In all his greatest acts, there was an element of self-seeking. Above all, he lacked stability. He tied himself to no man, to no party, to no single cause. Baldwin was right to fear that Lloyd George would destroy the Conservative Party, as he had destroyed the Liberal Party." (38)

Andrew Bonar Law

Andrew Bonar Law, the leader of the Conservative Party, replaced David Lloyd George as prime minister. His first task was to persuade the French government to be more understanding of Germany's ability to pay war reparations. Under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles (1919), agreed to 226 billion gold marks. In 1921, the amount was reduced to 132 billion. However, they were still unable to pay the full amount and by the end of 1922, Germany was deeply in debt. Bonar Law suggested lowering the payments but the French refused and on 11th January, 1923, the French Army occupied the Ruhr. (39)

Bonar Law also had the problem of Britain's war debt to the United States. In January 1923 Bonar Law's chancellor, Stanley Baldwin, sailed to America to discuss a settlement. Initially the loans to Britain had been made at an interest rate of 5 per cent. Bonar Law urged Baldwin to get it reduced to 2.5 per cent, but the best American offer was for 3 per cent, rising to 3.5 per cent after ten years. This amounted to annual repayments of £25 million and £36 million, rising to £40 million. Baldwin, acting on his own initiative, accepted the American offer and announced to the British press that they were the best terms available. Bonar Law was furious and on 30th January announced at cabinet that he would resign rather than accept the settlement. However, the rest of the cabinet thought it was a good deal and he was forced to withdraw his threat. (40)

The American settlement meant a 4 per cent increase in public expenditure at a time when Bonar Law was committed to a policy of reducing taxes and public expenditure. This brought him into conflict with the trade union movement that was deeply concerned by growing unemployment. Robert Blake, the author of The Conservative Party from Peel to Churchill (1970) argued that Bonar Law was not sure how the working class would react to this situation. Could they gain their support "by making moderate concessions" or to make "a direct appeal to the working-class over the heads of the bourgeoisie, a new form of Tory radicalism?" (41)

In April 1923, Bonar Law began to have problems talking. On the advice of his doctor, Sir Thomas Horder, he took a month's break from work, leaving Lord George Curzon to preside over the cabinet and Stanley Baldwin to lead in the House of Commons. Horder examined Bonar Law in Paris on 17th May, and diagnosed him to be suffering from cancer of the throat, and gave him six months to live. Five days later Bonar Law resigned but decided against nominating a successor. (42)

John C. Davidson, the Conservative Party MP, sent a memorandum to King George V advising him on the appointment: "The resignation of the Prime Minister makes it necessary for the Crown to exercise its prerogative in the choice of Mr Bonar Law's successor. There appear to be only two possible alternatives. Mr Stanley Baldwin and Lord Curzon. The case for each is very strong. Lord Curzon has, during a long life, held high office almost continuously and is therefore possessed of wide experience of government. His industry and mental equipment are of the highest order. His grasp of the international situation is great."

Davidson pointed out that Baldwin also had certain advantages: "Stanley Baldwin has had a very rapid promotion and has by his gathering strength exceeded the expectations of his most fervent friends. He is much liked by all shades of political opinion in the House of Commons, and has the complete confidence of the City and the commercial world generally. He in fact typifies the spirit of the Government which the people of this country elected last autumn and also the same characteristics which won the people's confidence in Mr Bonar Law, i.e. honesty, simplicity and balance."

Given their relative merits, Davidson believed that the king should select Baldwin: "Lord Curzon temperamentally does not inspire complete confidence in his colleagues, either as to his judgement or as to his ultimate strength of purpose in a crisis. His methods too are inappropriate to harmony. The prospect of him receiving deputations as Prime Minister for the Miners' Federation or the Triple Alliance, for example, is capable of causing alarm for the future relations between the Government and labour, between moderate and less moderate opinion... The time, in the opinion of many members of the House of Commons, has passed when the direction of domestic policy can be placed outside the House of Commons, and it is admitted that although foreign and imperial affairs are of vital importance, stability at home must be the basic consideration. There is also the fact that Lord Curzon is regarded in the public eye as representing that section of privileged conservatism which has its value, but which in this democratic age cannot be too assiduously exploited." (43)

Arthur Balfour, the prime minister between July, 1902 and December, 1905, was also consulted and he suggested the king could chose Baldwin. (44) "Balfour... pointed out that a Cabinet already over-weighted with peers would be open to even greater criticism if one of them actually became Prime Minister; that, since the Parliament Act of 1911, the political centre of gravity had moved more definitely than ever to the Lower House; and finally that the official Opposition, the Labour party, was not represented at all in the House of Lords." (45)

Andrew Bonar Law was the shortest-serving prime minister of the 20th century. He is also the only British prime minister to be born outside the British Isles. Bonar Law died aged 65, on 30th October, 1923. His estate was probated at £35,736 (approximately £1,900,000 as of 2017). (46)

Stanley Baldwin was faced with growing economic problems. This included a high-level of unemployment. Baldwin believed that protectionist tariffs would revive industry and employment. However, Bonar Law had pledged in 1922 that there would be no changes in tariffs in the present parliament. Baldwin came to the conclusion that he needed a General Election to unite his party behind this new policy. On 12th November, Baldwin asked the king to dissolve parliament. (47)

During the election campaign, Baldwin made it clear that he intended to impose tariffs on some imported goods: "What we propose to do for the assistance of employment in industry, if the nation approves, is to impose duties on imported manufactured goods, with the following objects: (i) to raise revenue by methods less unfair to our own home production which at present bears the whole burden of local and national taxation, including the cost of relieving unemployment; (ii) to give special assistance to industries which are suffering under unfair foreign competition; (iii) to utilise these duties in order to negotiate for a reduction of foreign tariffs in those directions which would most benefit our export trade; (iv) to give substantial preference to the Empire on the whole range of our duties with a view to promoting the continued extension of the principle of mutual preference which has already done so much for the expansion of our trade, and the development, in co-operation with the other Governments of the Empire, of the boundless resources of our common heritage." (48)

The Labour Party election manifesto completely rejected this argument: "The Labour Party challenges the Tariff policy and the whole conception of economic relations underlying it. Tariffs are not a remedy for Unemployment. They are an impediment to the free interchange of goods and services upon which civilised society rests. They foster a spirit of profiteering, materialism and selfishness, poison the life of nations, lead to corruption in politics, promote trusts and monopolies, and impoverish the people. They perpetuate inequalities in the distribution of the world's wealth won by the labour of hands and brain. These inequalities the Labour Party means to remove." (49)

In the 1923 General Election, the Labour Party won 191 seats. Although the Conservative Party had 258 seats, Herbert Asquith announced that the Liberal Party would not keep the Tories in office. If a Labour Government were ever to be tried in Britain, he declared, "it could hardly be tried under safer conditions". On 22nd January, 1924 Stanley Baldwin resigned. At midday, the 57 year-old, Ramsay MacDonald went to Buckingham Palace to be appointed prime minister. He later recalled how George V complained about the singing of the Red Flag and the La Marseilles, at the Labour Party meeting in the Albert Hall a few days before. MacDonald apologized but claimed that there would have been a riot if he had tried to stop it. (50)

Ramsay MacDonald: Childhood

James Ramsay MacDonald, the illegitimate son of Anne Ramsay, a maidservant, was born in Lossiemouth, Morayshire, on 12th October, 1866. His father, James MacDonald, was a ploughman on a farm some miles away. Anne's mother, Isabella, held firm Calvinist beliefs and objected to James and Anne marrying: "The young couple, however, were exonerated by their local free kirk as they were not living in sin, in a rural area which had a high incidence of births out of wedlock." (51)

MacDonald went to the parish school at Drainie. At fifteen, after a few months working on a nearby farm, MacDonald was appointed as a pupil teacher. His appointment saved him from a lifetime working on the land. During his time as pupil teacher he read widely including Progress and Poverty, by Henry George. The author believed that higher taxes on the rich could help to deal with the increasing number of people living in poverty. MacDonald was also influenced by the political radicalism of the fishermen and farm workers and by 1884 considered himself to be a Christian Socialist. (52)

In 1885, MacDonald left Scotland to take up a position as an assistant to a Bristol clergyman who planned to establish a Boys' and Young Men's Guild at St Stephen's Church. He hoped to become a social worker or a teacher. He was to admit several years later: "Something is constantly saying to me that I will do nothing myself but that I will enable someone else to do something." (53)

Later that year MacDonald joined the Social Democratic Federation (SDF), the first Marxist political group in Britain. MacDonald became the librarian, organizing the sale of the SDF's newspaper, Justice. MacDonald later recalled that the small group met in a workmen's cafe. "We had all the enthusiasm of the early Christians in those days. We were few and the gospel was new. The second coming was at hand." (54)

MacDonald left a couple of months later after he heard that during the 1885 General Election, two of the SDF leaders, Henry M. Hyndman and Henry H. Champion, without consulting their colleagues, accepted £340 from the Conservative Party to run parliamentary candidates in Hampstead and Kensington. The objective being to split the Liberal vote and therefore enable the Conservative candidate to win. MacDonald claimed that the actions of Hyndman and Champion "lacked a spirit of fairness". (55)

In his resignation letter he wrote: "If practical Socialism means an autocracy or the Government of a Cabal I for one will have nothing to do with it... To read that paper (Justice) one would think the SDF's hand was against all other Socialist societies in England and that its duty was to heap slander of all sorts upon them... We have over and over again had to read arguments in favour of Socialism that never went deeper than calling an opponent an 'outrageous old hypocrite', 'a bloodsucker', 'ignorant, and many other epithets as delicious as the fumes of a Billingsgate market... It has been plainly shown in the history of the Federation that the great virtues it recognises are unscrupulousness, unfairness and slander. Be it so! I hope there may be many who can now see to what they have been trusting, and how they have been used, many who love the grand principles of Socialism more than the distorted doctrines of the Federation and who have the courage and manliness to act accordingly." (56)

In 1886 MacDonald moved to London and obtained a job as an invoice clerk in a city warehouse. Living in cheap lodgings in Kentish Town and attended evening classes where he studied for a science scholarship in the Birkbeck Institute and the City of London College. He hoped to win a scholarship to train as a teacher at a school South Kensington. "When his health broke down from poverty and overwork he lost the chance of bettering himself through formal education." (57)

After he recovered his health, MacDonald was employed as private secretary to Thomas Lough, the Liberal Party candidate for West Islington. Lough, an Irish nonconformist and tea merchant was a loyal follower of William Ewart Gladstone. According to his biographer, "the 21-year-old Scot entered the world of metropolitan middle-class Liberalism but also moved among the radical and Labour figures who dominated the local party." (58)

Soon after arriving in London he joined the Fabian Society. Another member, George Bernard Shaw, said he had the bearing of an army officer. Beatrice Webb, a founder member of the group, agreed to employ MacDonald as a "lecturer in the provinces". MacDonald wanted to give talks in London but Webb rejected that idea: "He is not good enough for that work; he has never had the time to do any sound original work, or even learn the old stuff well. Moreover he objects altogether to diverting 'socialist funds' to education... The truth is that we and MacDonald are opposed on a radical issue of policy." (59)

In the 1880s working-class political representatives stood in parliamentary elections as Liberal-Labour candidates. MacDonald had hopes of becoming the Lib-Lab candidate for Dover. A local newspaper made it clear that MacDonald was on the extreme left of the Liberal Party: "Mr. MacDonald... with true Scotch sturdiness he stuck to his guns, and in a speech of over an hour's duration, during which he was subjected to continual interruptions, he explained the relationship of the Labour party to the Liberal party and the programme on which he should fight the next Parliamentary election... In conclusion, Mr. MacDonald said that he had kept them rather long but he had done so mainly for the purpose of teaching certain interests in Dover a lesson, and if the same policy were adopted at every meeting he should do exactly as he had done that night." (60)

After the 1885 General Election there were eleven of these Liberal-Labour MPs. Some socialists like Keir Hardie, began to argue that the working class needed their own independent political party. This feeling was strong in Manchester and in 1892 Robert Blatchford, the editor of the socialist newspaper, the Clarion joined with Richard Pankhurst to form the Manchester Independent Labour Party. (61)

Independent Labour Party

The activities of the Manchester group inspired Liberal-Labour MPs to consider establishing a new national working class party. Under the leadership of Keir Hardie, the Independent Labour Party was formed in 1893. It was decided that the main objective of the party would be "to secure the collective ownership of the means of production, distribution and exchange". Leading figures in this new organisation included Robert Smillie, George Bernard Shaw, Tom Mann, George Barnes, Pete Curran, John Glasier, Katherine Glasier, Henry H. Champion, Ben Tillett, Philip Snowden and Edward Carpenter. (62)

Ramsay MacDonald joined in 1894 and the following year was selected as the ILP candidate for Southampton. At a meeting in May 1895, Margaret Gladstone attended one of his meetings. She noted that his red tie and curly hair made him look "horribly affected". However, she sent him a £1 contribution to his election fund. A few days later she became one of his campaign workers. At the 1895 General Election, MacDonald, along with the other twenty-seven Independent Labour Party candidates, was defeated and overall, the party won only 44,325 votes. (63)

If you find this article useful, please feel free to share on websites like Reddit. Please visit our support page. You can follow John Simkin on Twitter, Google+ & Facebook or subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

The following year Ramsay and Margaret began meeting at the Socialist Club in St. Bride Street and at the British Museum, where they both had readers' tickets. In a letter she admitted that before she met him she had been terribly lonely: "But when I think how lonely you have been I want with all my heart to make up to you one tiny little bit for that. I have been lonely too - I have envied the veriest drunken tramps I have seen dragging about the streets if they were man and woman because they had each other... This is truly a love letter: I don't know when I shall show it you: it may be that I never shall. But I shall never forget that I have had the blessing of writing it." (64)

They decided to get married and in a letter she wrote to MacDonald on 15th June, 1896 about her situation: "My financial prospects I am very hazy about, but I know I shall have a comfortable income. At present I get £80 allowance (besides board & lodging, travelling and postage); my married sister has, I think about £500 all together. When my father dies we shall each have our full share, and I suppose mine will be some hundreds a year... My ideal would be to live a simple life among the working people, spending on myself whatever seemed to keep me in best efficiency, and giving the rest to public purposes, especially Socialist propaganda of various kinds." (65)

After they married in 1897, Margaret MacDonald was able to finance her husband's political career from her private income of £500 a year. "The marriage was a political partnership, albeit an uneven one. Margaret continued with her own public work, but she also coped with her husband's social awkwardness. About once every three weeks, they were 'at home' to progressive trade unionists and Labour activists, Socialist leaders and radical intellectuals and later to foreign Socialists, dominion Labour leaders and colonial nationalists. These gatherings were important for MacDonald's political career." (66)

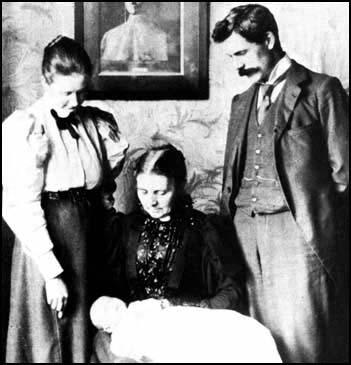

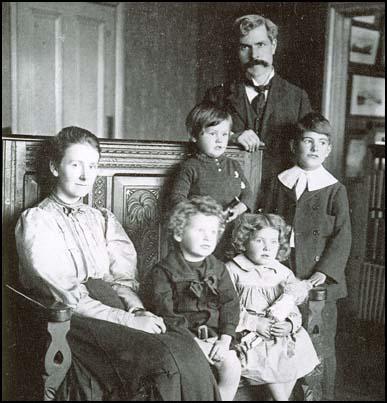

The marriage was a very happy one, and over the next few years they had six children: Alister (1898), Malcolm (1901), Ishbel (1903), David (1904), Joan (1908) and Shelia (1910). Bruce Glasier wrote: "Margaret MacDonald might easily have been taken for the nursemaid in a small middle-class family. Her naivete, simplicity, unselfishness and amazing capacity for organisation and helpful work made her one of the best liked women I have known. There was little in her to attract men, as men, but everything to attract women and men who had enthusiasm for public work." (67)

Keir Hardie, the leader of the Independent Labour Party and George Bernard Shaw of the Fabian Society, believed that for socialists to win seats in parliamentary elections, it would be necessary to form a new party made up of various left-wing groups. On 27th February 1900, representatives of all the socialist groups in Britain met with trade union leaders at the Congregational Memorial Hall in Farringdon Street. After a debate the 129 delegates decided to pass Hardie's motion to establish "a distinct Labour group in Parliament, who shall have their own whips, and agree upon their policy, which must embrace a readiness to cooperate with any party which for the time being may be engaged in promoting legislation in the direct interests of labour." To make this possible the Conference established a Labour Representation Committee (LRC). This committee included two members from the Independent Labour Party (Keir Hardie and James Parker), two from the Social Democratic Federation (Harry Quelch and James Macdonald), one member of the Fabian Society (Edward R. Pease), and seven trade unionists (Richard Bell, John Hodge, Pete Curran, Frederick Rogers, Thomas Greenall, Allen Gee and Alexander Wilkie). (68)

Whereas the ILP, SDF and the Fabian Society were socialist organizations, the trade union leaders tended to favour the Liberal Party. As Edmund Dell pointed out in his book, A Strange Eventful History: Democratic Socialism in Britain (1999): "The ILP was from the beginning socialist... but the trade unions which participated in the foundation were not yet socialist. Many trade union leaders were, in politics, inclined to Liberalism and their purpose was to strengthen labour representation in the House of Commons under Liberal party auspices. Hardie and the ILP nevertheless wished to secure the collaboration of trade unions. They were therefore prepared to accept that the LRC would not at the outset have socialism as its objective." (69) Henry Pelling argued: "The early components of the Labour Party formed a curious mixture of political idealists and hard-headed trade unionists: of convinced Socialists and loyal but disheartened Gladstonians". (70)

Ramsay MacDonald and the Labour Party

Ramsay MacDonald was chosen as the secretary of the LRC. One reason for this was as he was financed by his wealthy wife, he did not have to be paid a salary. The LRC put up fifteen candidates in the 1900 General Election and between them they won 62,698 votes. Two of the candidates, Keir Hardie and Richard Bell won seats in the House of Commons. Hardie was the leader of the ILP but Bell, the General Secretary of the Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants, once in Parliament, associated himself with the Liberal Party. (71)

Ramsay MacDonald was totally against the Boer War as he saw it as a consequence of imperialism. He wrote that "further extensions of Empire are only the grabbings of millionaires on the hunt". He joined forces with John Hobson to move a resolution condeming the war at a meeting of the Fabian Society. It was defeated and George Bernard Shaw wrote to MacDonald claiming: "I don't believe that the causes of the war menace our democracy. Quite the contrary. I don't believe that the capitalists have created or could have created the situation they are now exploiting for all its worth." After failing to win the vote, MacDonald, along with thirteen others, including Walter Crane and Emmeline Pankhurst, resigned from the Fabian Society. (72)

Ramsay MacDonald became the Labour Representation Committee candidate for Leicester. The constituency elected two members and the other candidate expected to win was Henry Broadhurst, who represented the Liberal Party. The local newspaper was impressed with MacDonald: "Mr MacDonald is a tall, strong, vigorous young man, and has evidently got a lot of fight in him. He appears to have a great deal of nervous electric energy as well as abundant muscular force. He stands upright with every inch of his measurement - with conscious power." (73)

In February, 1903, Ramsay MacDonald and Keir Hardie had meetings with Herbert Gladstone and other leading members of the Liberal Party about the possibility of an electoral pact. As a result of these discussions it was agreed that such a deal would prove very harmful to the Conservative Party: "An arrangement would mean that the future for both the Liberals and the LRC would be very bright and encouraging. It would mean votes for the Liberals from erstwhile Liberal working men and even from Tory working men. The main benefit, however, would be the effect on the public mind of seeing the opponents of the Government united." (74)

At its conference that year it increased subscriptions which gave it an annual income approaching £5,000. The LRC also established a compulsory parliamentary fund for the payment of members of the House of Commons. At that time MPs were not paid a wage. This move provided an effective way of making members of Parliament and parliamentary candidates toe the party line. (75)

1906 General Election

The LRC did much better in the 1906 General Election with twenty nine successful candidates winning their seats. MacDonald won his seat and other successes included James Keir Hardie (Merthyr Tydfil), Philip Snowden (Blackburn), Arthur Henderson (Barnard Castle), George Barnes (Glasgow Blackfriars), Will Thorne (West Ham) and Fred Jowett (Bradford). At a meeting on 12th February, 1906, the group of MPs decided to change from the LRC to the Labour Party. Hardie was elected chairman and MacDonald was selected to be the party's secretary. (76)

This success was due to the secret alliance with the Liberal Party. This upset left-wing activists as they wanted to use elections to advocate socialism. (77) However, of their 29 MPs only 18 were socialists. Hardie was elected chairman of the party by one vote, against Shackleton, the trade union candidate. His victory was based on recognition of his role in forming the Labour Party rather than his socialism. (78)

Arthur Henderson, George Barnes, Ramsay Macdonald, Philip Snowden,

Will Crooks, Keir Hardie, John Hodge, James O'Grady and David Shackleton.

Some people in the party were worried about the new dominance of the trade union movement. The Clarion newspaper wrote: "There is probably not more than one place in Britain (if there is one) where we can get a Socialist into Parliament without some arrangement with Liberalism, and for such an arrangement Liberalism will demand a terribly heavy price - more than we can possibly afford." (79)

Labour MPs campaigned to reverse the Taff Vale judgment. In 1901 the Taff Vale Railway Company sued the Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants for losses during a strike. As a result of the case the union was fined £23,000. Up until this time it was assumed that unions could not be sued for acts carried out by their members. This court ruling exposed trade unions to being sued every time it was involved in an industrial dispute. As a result of Shackleton's efforts the House of Commons passed the 1906 Trades Disputes Act which removed trade union liability for damage by strike action. (80)

This was seen as a great victory for the Labour Party. The historian, Ralph Miliband, has argued: "The only issue on which the Labour Party was unambiguously pledged was the legislative reversal of the Taff Vale decision of 1901, which had seriously jeopardized the unions' right to strike, but which had also been of crucial importance to the LRC, since it was this above all else which had persuaded more unions that they did indeed require independent representation in the House of Commons, and who therefore agreed to affiliate to the LRC. The Trades Dispute Act... ultimately met the Trade Unions' demands could legitimately be claimed as a success for the Parliamentary Labour Party." (81)

At first Keir Hardie was chairman of the party in the House of Commons, but was not very good with dealing with internal rivalries within the party, and in 1908 resigned from the post and Arthur Henderson became leader. However, it was Ramsay MacDonald who held the most power. As David Marquand has pointed out: "The LRC conference unanimously elected him as secretary of the new body. He was the only person in the entire LRC whose responsibility was to the whole rather than to any of the constituent parts. He had no salary, little formal power, and few resources. But on the strategic questions that determined its fate, his was the decisive voice." (82)

In 1909 David Lloyd George announced what became known as the People's Budget. This included increases in taxation. Whereas people on lower incomes were to pay 9d. in the pound, those on annual incomes of over £3,000 had to pay 1s. 2d. in the pound. Lloyd George also introduced a new supertax of 6d. in the pound for those earning £5000 a year. Other measures included an increase in death duties on the estates of the rich and heavy taxes on profits gained from the ownership and sale of property. Other innovations in Lloyd George's budget included labour exchanges and a children's allowance on income tax. (83)

Ramsay MacDonald argued that the Labour Party should fully support the budget. "Mr. Lloyd George's Budget, classified property into individual and social, incomes into earned and unearned, and followers more closely the theoretical contentions of Socialism and sound economics than any previous Budget has done." MacDonald went on to argue that the House of Lords should not attempt to block this measure. "The aristocracy... do not command the moral respect which tones down class hatreds, nor the intellectual respect which preserves a sense of equality under a regime of considerable social differences." (84)

During this period the Labour MPs gave its support to the Liberal government. The chief whip reported in 1910: Throughout this period I was always able to count on the support of the Labour Party." One Labour supporter asked: "How can the man in the street, whom we are continually importuning to forsake his old political associations, ever be led to believe that the Labour Party is in any way different to the Liberal Party, when this sort of thing is recurring." (85)

Arthur Henderson did not have the full-support of the party and in 1910 he decided to retire as chairman. Henderson thought that MacDonald should become the new leader. As David Marquand, the author of Ramsay MacDonald (1977) pointed out: "It is unlikely that he did so out of a sudden access of personal affection, or even out of admiration for MacDonald's character and abilities. He wanted MacDonald as chairman, partly because he wanted to be party secretary himself and believed correctly that he would be a good one, partly because he believed - again correctly - that MacDonald was the only potential candidate capable of reconciling the ILP to the moderate line favoured by the unions." (86)

Ramsay MacDonald was expected to become the new leader but in February he suffered two shattering emotional blows. On 3rd February his youngest son, David, died of diphtheria. On 4th July, 1910, MacDonald wrote: "My little David's birthday... Sometimes I feel like a lone dog in the desert howling from pain of heart. Constantly since he died my little boy has been my companion. He comes and sits with me especially on my railway journey and I feel his little warm hand in mine. That awful morning when I was awakened by the telephone bell, and everything within me shrunk in fear for I knew I was summoned to see him die, comes back often too." (87) Eight days later his mother also died. It was therefore decided that George Barnes should become chairman instead of MacDonald. A few months later Barnes wrote to MacDonald saying he did not want the chairmanship and was "only holding the fort". He continued, "I should say it is yours anytime". (88)

Leader of the Labour Party

The 1910 General Election saw 40 Labour MPs elected to the House of Commons. Two months later, on 6th February, 1911, George Barnes sent a letter to the Labour Party announcing that he intended to resign as chairman. At the next meeting of MPs, Ramsay MacDonald was elected unopposed to replace Barnes. Arthur Henderson now became secretary. According to Philip Snowden, a bargain had been struck at the party conference the previous month, whereby MacDonald was to resign the secretaryship in Henderson's favour, in return for becoming chairman."

On 20th July 1911, Ramsay MacDonald arranged for Margaret MacDonald to meet William Du Bois in the House of Commons. He later explained: "A little after noon she joined me at the House of Commons with one whom she had desired to meet ever since she had read his book on the negro, Professor Du Bois; that afternoon we went to country for a weekend rest. She complained of being stiff, and jokingly showed me the finger carrying her marriage and engagement rings. It was badly swollen and discoloured, and I expressed concern. She laughed away my fears... On Saturday she was so stiff that she could not do her hair, and she was greatly amused by my attempts to help her. On Sunday she had to admit that she was ill and we returned to town. Then she took to bed."

According to Bruce Glasier she was treated by Dr. Thomas Barlow, who told MacDonald that he could not save her. "When she heard that she was doomed, she was silent, and said with a slight tremble in her voice, I am very sorry to leave you - you and the children - alone. She never wept - never to the end. She asked if the children could be brought to see her. When the boys were brought to her, she spoke to each one separately. To the boys she said, I wish you only to remember one wish of your mother's - never marry except for love." (89)

Margaret MacDonald died on 8th September 1911, at her home, Lincoln's Inn Fields, from blood poisoning due to an internal ulcer. Her body was cremated at Golders Green on 12th September and the ashes were buried in Spynie Churchyard, a few miles from Lossiemouth. His son, Malcolm MacDonald, later recalled: "At the time of my mother's death... my father's grief was absolutely horrifying to see. Her illness and her death had a terrible effect on him of grief; he was distracted; he was in tears a lot of time when he spoke to us... it was almost frightening to a youngster like myself." (90)

Ramsay MacDonald wrote a short memoir of his wife, which was privately printed and circulated to friends. He told Katharine Glasier: "I felt myself hearing her approval of it, so much so that I seemed to see her hand on your shoulder as you wrote - and grew foolishly weakly blind with tears for the pain that was there." Katharine encouraged him to remarry. He rejected the idea and when his son, Malcolm MacDonald, made the same suggestion he replied: "My heart is in the grave." The income from Margaret's trust fund - now around £800 a year - was paid to him. This enabled him to employ a woman to look after the children and the household at Lincoln's Inn Fields.

The Liberal government's next major reform was the 1911 National Insurance Act. This gave the British working classes the first contributory system of insurance against illness and unemployment. All wage-earners between sixteen and seventy had to join the health scheme. Each worker paid 4d a week and the employer added 3d. and the state 2d. In return for these payments, free medical attention, including medicine was given. Those workers who contributed were also guaranteed 7s. a week for fifteen weeks in any one year, when they were unemployed. (91)

MacDonald declared in the House of Commons that the premiums were too high and the balance between state, employer and employee was unfair. However, he believed that the Labour Party should try to get the measure modified. Some leading figures in the movement, including Keir Hardie, Philip Snowden, Will Thorne and George Lansbury, disagreed and called for the bill to be rejected. MacDonald was furious about this rebellious behaviour. He continued to negotiate with David Lloyd George and managed to get important concessions including low-paid workers exempted from contributions. (92)

Lloyd George's reforms were strongly criticised and some Conservatives accused him of being a socialist. There was no doubt that he had been heavily influenced by Fabian Society pamphlets on social reform that had been written by Beatrice Webb, Sidney Webb and George Bernard Shaw. However, some Fabians "feared that the Trade Unions might now be turned into Insurance Societies, and that their leaders would be further distracted from their industrial work." (93)

John Bruce Glasier argued that Ramsay MacDonald gave him the impression that he had lost faith in socialism and wanted to move the Labour Party to the right: "I noticed that Ramsay MacDonald in speaking of the appeal we should send out for capital used the word 'Democratic' rather than 'Labour' or 'Socialist' as describing the character of the newspaper. I rebulked him flatly and said we would have no 'democratic' paper but a Socialist and Labour one - boldly proclaimed. Why does MacDonald always seem to try and shirk the word Socialism except when he is writing critical books about the subject." (94)

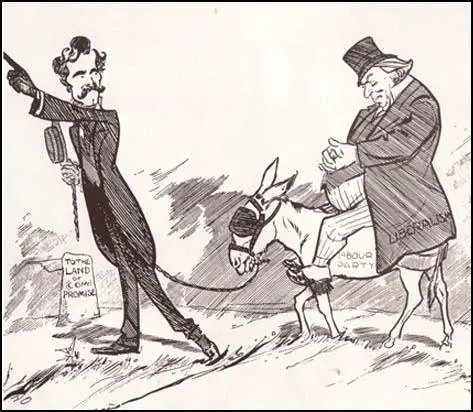

ON THE WAY TO NOWHERE

Ramsay MacDonald (leading the Labour Party into the Land of Compromise):

"Forward, my four-footed brother, forward, and in spite of all they say, let us

continue to take advantage, in the devilish diplomatic way we are at

present doing, of the fact that the Old Party is going in the same direction!"

Ramsay MacDonald clashed with some members of the party over votes for women. He had argued for many years that women's suffrage that was a necessary part of a socialist programme. He was therefore able to negotiate an agreement with the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies for joint action in by-elections. In October, 1912, it was claimed that £800 of suffragist money had been spent on Labour candidatures. (95)

However, some leaders of the Labour Party, including Keir Hardie and George Lansbury, supported the campaign of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), MacDonald rejected their use of violence: "I have no objection to revolution, if it is necessary but I have the very strongest objection to childishness masquerading as revolution, and all that one can say of these window-breaking expeditions is that they are simply silly and provocative. I wish the working women of the country who really care for the vote ... would come to London and tell these pettifogging middle-class damsels who are going out with little hammers in their muffs that if they do not go home they will get their heads broken." (96)

MacDonald also pointed out, the WSPU wanted votes for women on the same terms as men, and specifically not votes for all women. He considered this unfair as at this time only a third of men had the vote in parliamentary elections. MacDonald's friend, John Bruce Glasier, recorded in his diary after a meeting with Emmeline Pankhurst and Christabel Pankhurst, that they were guilty of "miserable individualist sexism" and that he was strongly against supporting the organisation. (97)

In 1912 MacDonald formed a friendship with Margaret Sackville. It has been claimed that she was his mistress for fifteen years. Under the influence of MacDonald, Sackville became a socialist and a pacifist. The surviving letters, which date from 1913, show that MacDonald proposed at least three times to Sackville, but each time he was rejected. In one letter MacDonald wrote: "Dearest beloved, it is such a beautiful morning that you ought to be here and we should be walking in the garden. And if we were walking in the garden, what more should we do where the bushes hid us?" (98)

Patrick Barkham has pointed out: "It was a passion they could not make public, a love doomed to be declared in scribbled letters or stolen moments when they walked together. Ramsay MacDonald was the ambitious, illegitimate son of a farm labourer... Lady Margaret Sackville was the youngest child of the seventh Earl de la Warr, a poet and a society beauty who became his lover. They were separated not only by class but by religion. Born in Lossiemouth, Morayshire, MacDonald was raised in the Presbyterian church and, as an adult, joined the Free Church of Scotland. Born in Mayfair, London, and nearly 15 years his junior, Lady Margaret was Roman Catholic." (99)

First World War

The Labour Party was completely divided by their approach to the First World War. Those who opposed the war, included Ramsay MacDonald, Keir Hardie, Philip Snowden, John Bruce Glasier, George Lansbury, Alfred Salter, William Mellor and Fred Jowett. Others in the party such as Arthur Henderson, George Barnes, J. R. Clynes, William Adamson, Will Thorne and Ben Tillett believed that the movement should give total support to the war effort. (100)

Keir Hardie made a speech on 2nd August, 1914, where he called on "the governing class... to respect the decision of the overwhelming majority of the people who will have neither part nor lot in such infamy... Down with class rule! Down with the rule of brute force! Down with war! Up with the peaceful rule of the people!" (101)

Ramsay MacDonald agreed and stated that he would not encourage his members to take part in the war. "Out of the darkness and the depth we hail our working-class comrades of every land. Across the roar of guns, we send sympathy and greeting to the German Socialists. They have laboured increasingly to promote good relations with Britain, as we with Germany. They are no enemies of ours but faithful friends." (102)

On 5th August, 1914, the parliamentary party voted to support the government's request for war credits of £100,000,000. Ramsay MacDonald immediately resigned the chairmanship and the pro-war Arthur Henderson was elected in his place. (103) MacDonald wrote in his diary: "I saw it was no use remaining as the Party was divided and nothing but futility could result. The Chairmanship was impossible. The men were not working, were not pulling together, there was enough jealously to spoil good feeling. The Party was no party in reality. It was sad, but glad to get out of harness." (104)

Five days later MacDonald had a meeting with Philip Morrel, Norman Angell, E. D. Morel, Charles Trevelyan and Arthur Ponsonby. They decided, in MacDonald's words, "to form a committee to voice our views". A meeting was held and after considering names such as the Peoples' Emancipation Committee and the Peoples' Freedom League, they selected the Union of Democratic Control. Other members included included J. A. Hobson, Charles Buxton, Frederick Pethick-Lawrence, Arnold Rowntree, Morgan Philips Price, George Cadbury, Helena Swanwick, Fred Jowett, Tom Johnston, Philip Snowden, Ethel Snowden, David Kirkwood, William Anderson, Isabella Ford, H. H. Brailsford, Israel Zangwill, Bertrand Russell, Konni Zilliacus, Margaret Sackville and Olive Schreiner.

It was agreed that the main reasons for the conflict was the secret diplomacy of people like Britain's foreign secretary, Sir Edward Grey. They decided that the UDC should have three main objectives: (i) that in future to prevent secret diplomacy there should be parliamentary control over foreign policy; (ii) there should be negotiations after the war with other democratic European countries in an attempt to form an organisation to help prevent future conflicts; (iii) that at the end of the war the peace terms should neither humiliate the defeated nation nor artificially rearrange frontiers as this might provide a cause for future wars. (105)

Ramsay MacDonald came under attack from newspapers because of his opposition to the First World War. On 1st October 1914, The Times published a leading article entitled Helping the Enemy, in which it wrote that "no paid agent of Germany had served her better" that MacDonald had done. The newspaper also included an article by Ignatius Valentine Chirol, who argued: "We may be rightly proud of the tolerance we display towards even the most extreme licence of speech in ordinary times... Mr. MacDonald' s case is a very different one. In time of actual war... Mr. MacDonald has sought to besmirch the reputation of his country by openly charging with disgraceful duplicity the Ministers who are its chosen representatives, and he has helped the enemy State ... Such action oversteps the bounds of even the most excessive toleration, and cannot be properly or safely disregarded by the British Government or the British people." (106)

In May 1915, Arthur Henderson, became the first member of the Labour Party to hold a Cabinet post when Herbert Asquith invited him to join his coalition government. John Bruce Glasier commented in his diary: "This is the first instance of a member of the Labour Party joining the government. Henderson is a clever, adroit, rather limited-minded man - domineering and a bit quarrelsome - vain and ambitious. He will prove a fairly capable official front-bench man, but will hardly command the support of organised Labour." (107)

Horatio Bottomley, argued in the John Bull Magazine that Ramsay MacDonald and James Keir Hardie, were the leaders of a "pro-German Campaign". On 19th June 1915 the magazine claimed that MacDonald was a traitor and that: "We demand his trial by Court Martial, his condemnation as an aider and abetter of the King's enemies, and that he be taken to the Tower and shot at dawn." (108)

On 4th September, 1915, the magazine published an article which made an attack on MacDonald's background. "We have remained silent with regard to certain facts which have been in our possession for a long time. First of all, we knew that this man was living under an adopted name - and that he was registered as James MacDonald Ramsay - and that, therefore, he had obtained admission to the House of Commons in false colours, and was probably liable to heavy penalties to have his election declared void. But to have disclosed this state of things would have imposed upon us a very painful and unsavoury duty. We should have been compelled to produce the man's birth certificate. And that would have revealed what today we are justified in revealing - for the reason we will state in a moment... it would have revealed him as the illegitimate son of a Scotch servant girl!" (109)

In his diary, MacDonald recorded his reaction to the article. "On the day when the paper with the attack was published, I was travelling from Lossiemouth to London in the company as far as Edinburgh with the Dowager Countess De La Warr, Lady Margaret Sackville and their maid... I saw the maid had John Bull in her hand. Sitting in the train, I took it from her and read the disgusting article. From Aberdeen to Edinburgh, I spent hours of the most terrible mental pain.... Never before did I know that I had been registered under the name of Ramsay, and cannot understand it now. From my earliest years my name has been entered upon lists, like the school register, etc. as MacDonald. My mother must have made a simple blunder or the registrar must have made a clerical error." (110)

Ramsay MacDonald received many letters of support, including this one from a long-term opponent to his anti-war activities: "For your villainy and treason you ought to be shot and I would gladly do my country service by shooting you. I hate you and your vile opinions - as much as Bottomley does. But the assault he made on you last week was the meanest, rottenest lowdown dog's dirty action that ever disgraced journalism." (111)

In August 1915, a group of members of the Moray Golf Club, of which he was a member, submitted a motion demanding that MacDonald should be removed from the roll of members because of his opposition to the First World War. The motion was carried by 73 votes to 24. MacDonald wrote to the club secretary: "I am in receipt of your letter informing me that the Moray Golf Club has decided to become a political association with the Golf Course attached, and that it has torn up its rules in order that some of its members may give rein to their political prejudice and spite. Unfortunately, for some years, the visit of any prominent Liberal or Radical to the Moray Golf Club has been resented by a certain section which has not concealed its offensiveness either in the Club House or on the Course. Though I am, therefore, not sorry that the character of a number of members of the Moray Golf Club has been advertised to the world, I cannot help regretting that the Club, of which I was one of the earliest members, should be held up to public ridicule and contempt." (112)

After the overthrow of Tsar Nicholas II in Russia, socialists in Britain, France, Germany, Austria-Hungary, United States and Italy called for a conference in a neutral country to see if the First World War could be brought to an end. MacDonald wrote in his diary: "The great service which the Russian Revolution could render to Europe would be to bring about an understanding between the German Democracy and that of the Allied countries." He felt that "a sort of spring-tide of joy had broken out all over Europe." (113)

Arthur Henderson was sent by David Lloyd-George to speak to Alexander Kerensky, the leader of the Provisional Government in Russia. At a conference of the Labour Party held in London on 10th August, 1917, Henderson made a statement recommending that the Russian invitation to the Stockholm Conference should be accepted. Delegates voted 1,846,000 to 550,000 in favour of the proposal and it was decided to send Henderson and MacDonald to the peace conference. However, under pressure from President Woodrow Wilson, the British government had changed his mind about the wisdom of the conference and refused to allow delegates to travel to Stockholm. As a result of this decision, Henderson resigned from the government. (114)

Ramsay MacDonald warned repeatedly that if the British government and its allies, continued to insist on a military victory, the moderate socialists would lose control in Russia. He was therefore not suprised when Alexander Kerensky was deposed and replaced by Lenin and the Bolsheviks. He added that it was Britain's fault that "Russia now negotiates alone with Russia".

Herbert Tracey has argued that Henderson's resignation marked an important change in the development of the Labour Party: "The divergence of policy between him and the War Cabinet thus became clear, and he resigned from the Government, feeling that his future course of action must be guided by the decision of the party to which he belonged... One thing is certain: Mr Henderson's resignation from the War Cabinet had a vitally important and permanent effect upon the development of the political Labour Movement, by restoring its independence and enabling it to begin reorganising in preparation for the coming of the peace." (115)

William Adamson replaced Arthur Henderson as chairman of the party in October 1917. David W. Howell has argued: "His experience as effectively party leader in the Commons was unhappy. Many felt that he lacked the necessary qualities." Beatrice Webb commented in her diary: "He is a middle-aged Scottish miner, typical British proletarian in body and mind, with an instinctive suspicion of all intellectuals or enthusiasts... He has neither wit, fervour nor intellect; he is most decidedly not a leader, not even like Henderson, a manager of men." (116)

Ramsay MacDonald was the Labour candidate for Leicester East in the 1918 General Election. He did not consider he had much chance of winning has he had suffered four years of hostile press coverage. "Four years indignity, lying, blackguardism, have eaten like acid into me. Were I assassinated before it is all over would give no one who has followed the attacks cause for wonder." (117)

The coalitionist candidate, Gordon Hewart, concentrated on MacDonald's opposition to the war. He argued that MacDonald had "put an odious stain and stima upon the fair name of Leicester". He went on to say that this was not "an indelible stain" and "the citizens of Leicester now had the opportunity of wiping it away and of meting out to its author his well-merited reward." MacDonald lost the election by 15,000 votes. (118)

Other opponents of the war such as Philip Snowden, George Lansbury and Fred Jowett, also lost their seats. At the Party Conference that year the Labour Party decided to make a statement of objectives. This included: "To secure for the producers by hand or by brain the full fruits of their industry, and the most equitable distribution thereof that may be possible, upon the basis of the common ownership of the means of production and the best obtainable system of popular administration and control of each industry and service." (119)

The new Constitution had been drafted by Sidney Webb. It presented the case for a minimum standard of life for all, for full employment, public ownership and greater equality. (120) G.D.H. Cole described the Constitution as "an historic document of the greatest significance" because "it unequivocally committed the Labour Party to Socialist objectives". (121) Clement Attlee agreed and called it "an uncompromisingly Socialist document". (122)

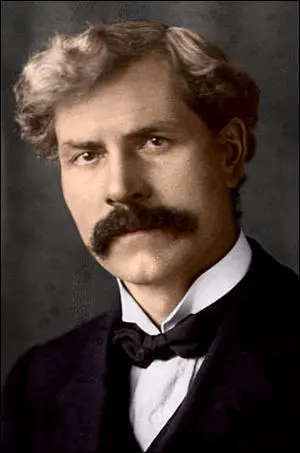

Ramsay MavDonald, deprived of his £400 parliamentary salary, found work as a writer and lecturer. He gradually rebuilt his political reputation. David Low, was a cartoonist from New Zealand, who had just arrived in Britain. He later wrote about he was "greatly impressed by Ramsay MacDonald, who looked to me a real leader. He seemed taller in those days and more craggy, as he stalked up and down. A handsome figure, fine voice, shabby blue serge suit, handlebar moustache solid black against solid white of hair forelock." (123)

At a meeting on 18th October, 1922, two younger members of the government, Stanley Baldwin and Leo Amery, urged the Conservative Party to remove David Lloyd George from power. Andrew Bonar Law disagreed as he believed that he should remain loyal to the Prime Minister. Two other senior ministers, Austen Chamberlain and Arthur Balfour also defended the coalition. However, it was a passionate speech by Baldwin: "The Prime Minister was described this morning in The Times, in the words of a distinguished aristocrat, as a live wire. He was described to me and others in more stately language by the Lord Chancellor as a dynamic force. I accept those words. He is a dynamic force and it is from that very fact that our troubles, in our opinion, arise. A dynamic force is a terrible thing. It may crush you but it is not necessarily right." The motion to withdraw from the coalition was carried by 187 votes to 87. (124)

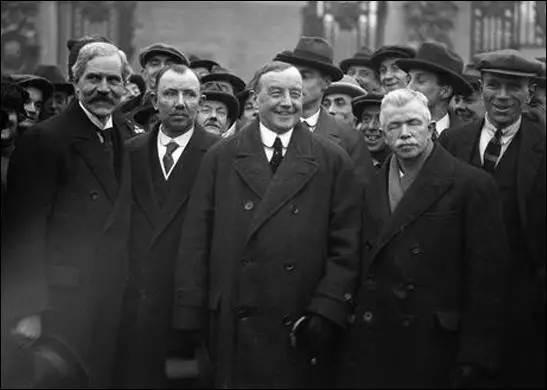

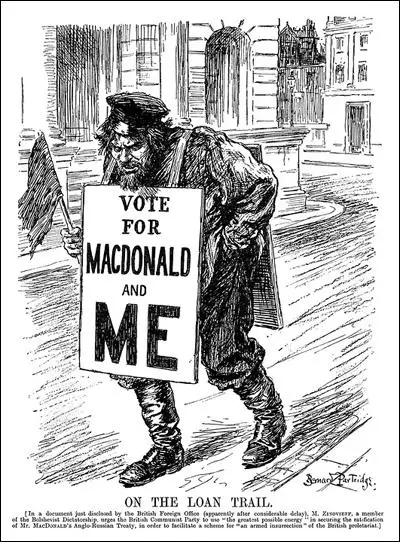

David Lloyd George was forced to resign and call a General Election. MacDonald had been forgiven for his opposition to the First World War by the time and was elected to represent Aberavon. Lloyd George's party only won 127 seats in the 1922 General Election. The Conservative Party now dominated the House of Commons with 344 seats and formed the next government. The Labour Party promised to nationalise the mines and railways, a massive house building programme and to revise the peace treaties, went from 57 to 142 seats, whereas the Liberal Party increased their vote and went from 36 to 62 seats. (125)