Marxism and the 19th Century

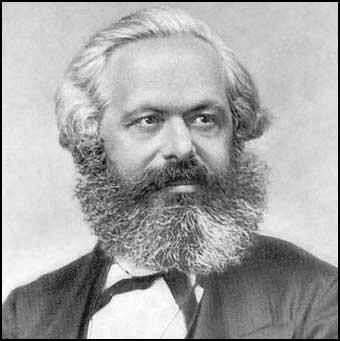

Karl Marx, the third of nine children and only surviving son of Hirschel and Henrietta Marx, was born in Trier, Germany, on 5th May 1818. His father was a lawyer and to escape anti-Semitism decided to abandon his Jewish faith when Karl was a child. Although the majority of people living in Trier were Catholics, Marx decided to become a Protestant. He also changed his name from Hirschel to Heinrich. (1)

Marx attended Friedrich-Wilhelm Gymnasium in Trier. At the age of seventeen he wrote about his ambitions for the future and the morality of the type of work he intended to do: ‘If he is working only for himself, he can become a famous scholar, a sage, a distinguished writer, but never a complete, a truly great, man." (2)

Marx entered Bonn University to study law in 1835. His father warned him to look after his body as well as his mind: "In providing really vigorous and healthy nourishment for your mind, do not forget that in this miserable world it is always accompanied by the body, which determines the well-being of the whole machine. A sickly scholar is the most unfortunate being on earth. Therefore, do not study more than your health can bear." (3)

At university he spent much of his time socialising and running up large debts. His father was horrified when he discovered that Karl had been wounded in a duel. His father asked him: "Is duelling then so closely interwoven with philosophy? Do not let this inclination, and if not inclination, this craze, take root. You could in the end deprive yourself and your parents of the finest hopes that life offers." (4)

Heinrich Marx agreed to pay off his son's debts but insisted that he moved to the more sedate Berlin University. At this time he also began a relationship with Jenny von Westphalen. She was the daughter of Baron Ludwig von Westphalen, and as Francis Wheen pointed out: "It may seem surprising that a twenty-two-year-old princess of the Prussian ruling class... should have fallen for a bourgeois Jewish scallywag four years her junior, rather than some dashing grandee with a braided uniform and a private income; but Jenny was an intelligent, free-thinking girl who found Marx's intellectual swagger irresistible. After ditching her official fiance, a respectable young second lieutenant, she became engaged to Karl in the summer of 1836." (5)

Karl Marx & Hegel

The move to Berlin resulted in a change in Marx and for the next few years he worked hard at his studies, especially when he switched from law to philosophy. Marx came under the influence of one of his lecturers, Bruno Bauer, whose atheism and radical political opinions got him into trouble with the authorities. Bauer introduced Marx to the writings of G. W. F. Hegel, who had been the professor of philosophy at the university until his death in 1831.

Marx wrote a long letter to his father describing his conversion to Hegel's theories: "There are moments in one's life, which are like frontier posts marking the completion of a period but at the same time clearly indicating a new direction. At such a moment of transition we feel compelled to view the past and the present with the eagle eye of thought in order to become conscious of our real position. Indeed, world history itself likes to look back in this way and take stock." (6)

His father was upset by his decision to abandon his law degree. Marx rarely replied to his parents' letters. He did not return home during university holidays and showed no interest in his family. His father appeared to accept defeat when he wrote: "I can only propose, advise. You have outgrown me; in this matter you are in general superior to me, so I must leave it to you to decide as you will." (7)

Karl Marx was especially impressed by Hegel's theory that a thing or thought could not be separated from its opposite. For example, the slave could not exist without the master, and vice versa. Hegel argued that unity would eventually be achieved by the equalising of all opposites, by means of the dialectic (logical progression) of thesis, antithesis and synthesis. This was Hegel's theory of the evolving process of history.

Heinrich Marx, aged fifty-seven, died of tuberculosis on 10th May 1838. Marx now had to earn his own living and he decided to become a university lecturer. After completing his doctoral thesis at the University of Jena, Marx hoped that his mentor, Bruno Bauer, would help find him a teaching post. However, Bauer was dismissed as a result of his outspoken atheism and was unable to help. (8)

Marx gradually began to question the purpose of philosophy: "Since every true philosophy is the intellectual quintessence of his time, the time must come when philosophy not only internally by its content, but also externally through its form, comes into contact and interaction with the real world of its day." (9) Three years later he commented: "The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways. The point, however, is to change it." (10)

Journalism

While in Berlin he met Moses Hess, a radical who called himself a socialist. Marx began attending socialist meetings organised by Hess who wrote to his friend, Berthold Auerbach, about the new member of the group: "He is a phenomenon who made a tremendous impression on me in spite of the strong similarity of our fields. In short you can prepare yourself to meet the greatest - perhaps the only genuine - philosopher of the current generation. When he makes a public appearance, whether in writing or in the lecture hall, he will attract the attention of all Germany... Dr Marx (that is my idol's name) is still a very young man - about twenty-four at the most. He will give medieval religion and philosophy their coup de grâce (an action or event that serves as the culmination of a bad or deteriorating situation); he combines the deepest philosophical seriousness with the most biting wit. Imagine Rousseau, Voltaire, Holbach, Lessing, Heine and Hegel fused into one person - I say fused not juxtaposed - and you have Dr. Marx." (11)

As well as his intellect his new friends commented on his unusual appearance. Gustav von Mevissen later recalled: "Karl Marx... was a powerful man of twenty-four whose thick black hair sprang from his cheeks, arms, nose and ears. He was domineering, impetuous, passionate, full of boundless self-confidence." Pavel Annenkov added: "He was most remarkable in his appearance. He had a shock of deep black hair and hairy hands... He looked like a man with the right and power to command respect." Friedrich Lessner believed that his looks gave him leadership qualities: "His brow was high and finely shaped, his hair thick and pitch-black... Marx was a born leader of the people." (12)

At these socialist meetings Marx discovered that he was not a great orator. He had a slight lisp and his gruff Rhenish accent was difficult to understand. He therefore decided to try journalism. However, his radical political views meant that most editors were unwilling to publish his articles. He moved to Cologne where the city's liberal opposition movement was fairly strong and had its own newspaper, The Rhenish Gazette. It has been pointed out by Eric Hobsbawm that the newspaper was funded by "a group of wealthy Cologne men in business and the professions and representing the moderate but loyal liberalism of the (non-clerical) Rhineland bourgeoisie". (13)

After six months and a number of articles, he became the newspaper's editorial director. He developed an aggressive style of writing and clearly "delighted in his talent for inflicting verbal violence". Karl Heinzen claimed he would use "logic, dialectics, learning... to annihilate anyone who would not see eye to eye with him. Marx, he said, wanted "to break windowpanes with cannon". According to the socialist politician, Wilhelm Liebknecht, Marx had the "style is the dagger used for a well-aimed thrust at the heart". (14)

A rival newspaper, accused Marx of editing a communist newspaper. Marx responded by arguing that "communist ideas in their present form possess even theoretical reality, and therefore can still less desire their practical realisation, or even consider it possible, will subject these ideas to thoroughgoing criticism." He was however interested in the ideas of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, who had recently published What is Property? (1840) and pointed out that the "sharp-witted work by Proudhon, cannot be criticised on the basis of superficial flashes of thought, but only after long and profound study." (15)

In a letter to his friend, Arnold Ruge, Marx admitted that the censor would not allow his socialist views to be published. Every edition of the newspaper had to be shown to Laurenz Dolleschall of the Cologne Police Department and any article he did not like could not appear in the newspaper. "Our newspaper has to be presented to the police to be sniffed at and if the police nose smells anything unChristian or UnPrussian, the newspaper is not allowed to appear." (16)

Even so, the provincial governor complained in November 1842 that the tone of the newspaper was "becoming more and more impudent". It was an article by Marx on accusing the authorities of ignoring "the wretched economic plight of Moselle wine-farmers who were unable to compete with the cheap, tariff-free wines being imported into Prussia from other German states." On 21st January 1843, the government banned the newspaper. (17)

Communism

Marx's friend, Arnold Ruge, offered him a position on a new journal based in Paris. Marx accepted but pointed out that "I am engaged to be married and I cannot, mist not and will not leave Germany without my intended wife.... She has fought the most violent battles, which almost undermined her health, partly against her pietistic aristocratic relatives... and partly against my own family, in which some priests and other enemies of mine have ensconced themselves... For years, therefore, my fiancée and I have been engaged in more unnecessary and exhausting conflicts than many who are three times our age." (18)

Marx married Jenny von Westphalen on 19th June, 1843. It was claimed that when she was dealing with "aristocratic mediocrities in gilded ballrooms she was witty, lively and supremely self-assured". However, in the early days of her relationship she admitted that: "I cannot say a word for nervousness, the blood stops flowing in my veins and my soul trembles". Over the next forty years she remained by his side helping him with his work and "since his handwriting was indecipherable to the untrained eye, he depended on her to transcribe" his writings. (19)

After a brief honeymoon Karl and Jenny Marx arrived in Paris, and became the joint-editor of the Deutsche-Französische Jahrbücher. He approached German philosopher Ludwig Feuerbach to write an article for the new journal. Marx had been very impressed with his work which provided a critique of Christianity and advocated liberalism, atheism, and materialism. However, Feuerbach, who disagreed with Marx's political activism, refused.

The first issue of the journal appeared in February 1844, and included contributions from his old mentor, Bruno Bauer, the Russian anarchist, Michael Bakunin and the radical son of a wealthy German industrialist, Friedrich Engels. The following month the Prussian government issued an arrest warrant against its editors on the grounds of high treason. (20)

Marx continued to write and developed his ideas on the concept of alienation. In Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts he developed his ideas on the concept of alienation. Marx identified three kinds of alienation in capitalist society. First, the worker is alienated from what he produces. Second, the worker is alienated from himself; only when he is not working does he feel truly himself. Finally, in capitalist society people are alienated from each other; that is, in a competitive society people are set against other people. Marx believed the solution to this problem was communism as this would enable the fulfilment of "his potentialities as a human." (21)

During this period Marx took a detailed look at religious belief. "Religious suffering is, at one and the same time, the expression of real suffering and a protest against real suffering. Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people. The abolition of religion as the illusory happiness of the people is the demand for their real happiness. To call on them to give up their illusions about their condition is to call on them to give up a condition that requires illusions. The criticism of religion is, therefore, in embryo, the criticism of that vale of tears of which religion is the halo." (22)

Marx than tackled the ideas of Feuerbach. James Richmond has pointed out that in Feuerbach's book, The Essence of Christianity (1841) he announced "his programme of doing what his philosophical mentors had shrunk from doing - to transform completely theology into anthropology, the love of God into the love of man, the service of God into the service of man. Man must be persuaded to turn his attention away from the other-worldly to the worldly, from some life which is allegedly to come to the present life, from heaven towards earth." (23)

He wrote to him saying that he had earned his lasting gratitude. "I am glad to have an opportunity of assuring you of the great respect and - if I may use the word - love which I feel for you... You have provided - I don't whether intentionally - a philosophical basis for socialism... The unity of man with man, which is based on the real differences between men, the concept of the human species brought down from the heaven of abstraction to the real earth, what is this but the concept of society." (24)

Feuerbach was not convinced by the arguments put forward by Marx. He replied that, in his opinion, "it would be rash to move from theory to practice until the theory itself had been honed to perfection". Marx, by contrast, believed the two were - or ought to be - inseparable and philosophers should concentrate on the "merciless criticism of all that exists".

In his article, Theses on Feuerbach (1845) Marx argued "The materialist doctrine concerning the changing of circumstances and upbringing forgets that circumstances are changed by men and that it is essential to educate the educator himself. This doctrine must, therefore, divide society into two parts, one of which is superior to society. The coincidence of the changing of circumstances and of human activity or self-changing can be conceived and rationally understood only as revolutionary practice... Philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways. The point, however, is to change it." (25)

Marx insisted that "the criticism of religion is the prerequisite of all criticism". He pointed out the contradictions of the role that Martin Luther played in the Protestant Reformation: "He destroyed faith in authority, but only by restoring the authority of faith. He transformed the priests into laymen, but only by transforming the laymen into priests. He freed mankind from external religiously, but only by making religiously the inner man. He freed the body from the chains, but only by putting the heart in chains." (26)

Marx agreed with Tom Paine that Christianity is a mask for the purpose of carrying on struggles for power over others. Paine, like Marx, was also a man of action. It was Paine who had "prepared the intellectual ground... for a more secular system of government and society in which, at a minimum, the freedom to believe and worship according to individual and group conscience required a pluralistic civil society". (27)

Economics and Society

Karl Marx decided to study economics. He began by reading the works of Adam Smith, David Ricardo and James Mill. He scribbled a running commentary as he went on. The first manuscript begins with the simple declaration: "Wages are determined by the fierce struggle between capitalist and worker. The capitalist inevitably wins. The capitalist can live longer without the worker than the worker can without him."

The only defence the workers have against capitalism is competition, which enables wages to rise and prices to fall. Marx believed that there was a tendency for monopolies to be created and therefore undermining the power of the workers: "The big capitalists ruin the small ones and a section of the former capitalists sinks into the class of the workers which, because of this increase in numbers, suffers a further depression of wages and becomes ever more dependent on the handful of big capitalists. Because the number of capitalists has fallen, competition for workers hardly exists any longer, and because the number of workers has increased, the competition among them has become all the more considerable, unnatural and violent." (28)

Marx pointed out that Adam Smith had warned of the dangers of a system that allowed individuals to pursue individual self-interest at the detriment of the rest of society. He was very much against the establishment of monopolies. "A monopoly granted either to an individual or to a trading company has the same effect as a secret in trade or manufactures. The monopolists, by keeping the market constantly under-stocked, by never fully supplying the effectual demand, sell their commodities much above the natural price, and raise their emoluments, whether they consist in wages or profit, greatly above their natural rate." (29)

Marx argued that even in times of economic growth, conditions do not get better for the worker. The only consequence is "overwork and early death, reduction to a machine, enslavement to capital". He is in competition with the machines. "Since the worker has been reduced to a machine, the machine can confront him as a competitor. The accumulation of capital enables industry to turn out an ever greater quantity of products. This leads to overproduction and unemployment.

The system is organised in such a way to benefit the employer. An industrialist can store his products of his factory until they fetch a decent price, whereas the worker's only product, his labour, loses its value completely if it is not sold at every instant. Unlike other commodities, labour can be neither accumulated nor saved. The employer is more fortunate, since capital is "stored-up labour".

Karl Marx pointed out that classical economists treated private property as a primordial human condition. However, the Industrial Revolution had shown that nothing is fixed or immutable. In the 18th century we had begun to see power being transferred from feudal landlords to industrialists. Feudal landowners had been efficient who had not attempted to extract the maximum profit from their property.

Under capitalism the worker devotes his life to producing objects which he does not own or control. His labour thus becomes a separate, external being which "exists outside him, independently of him and alien to him, and begins to confront him as an autonomous power; the life which he has bestowed on the object confronts him as hostile and alien". (30)

As Francis Wheen points out: "For Marx, alienated labour was not an eternal and inescapable problem of human consciousness but the result of a particular form of economic and social organization. A mother, for instance, isn't automatically estranged from her baby the moment it emerges from the womb... But she would feel very alienated indeed if, every time she gave birth, the squealing infant was immediately seized from her by some latter-down Herold. This, more or less, was the daily lot of the workers, forever producing what they could not keep. No wonder they felt less than human." (31)

Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels

While living in Paris he become a close friend of Friedrich Engels. As a young man his father sent him to England to help manage his cotton-factory in Manchester. Engels was shocked by the poverty in the city and began writing an account that was published as Condition of the Working Class in England (1844). Engels shared Marx's views on capitalism and after their first meeting Engels wrote that there was virtually "complete agreement in all theoretical fields became evident and our joint work dates from that time." (32)

Marx and Engels decided to work together. It was a good partnership, whereas Marx was at his best when dealing with difficult abstract concepts, Engels had the ability to write for a mass audience. For Engels, Marx was "the greatest living thinker", the "Darwin of the law of human historical evolution, the pathbreaker for humanity's future, a genius to whom he, a mere man of talent and intelligence, was justified in devoting his mind and money - even at the cost of continuing in the hated family cotton business to provide him with an income." (33)

While working on their first article together, The Holy Family, the Prussian authorities put pressure on the French government to expel Karl Marx from the country. On 25th January 1845, Marx received an order deporting him from France. Marx and Engels decided to move to Belgium, a country that permitted greater freedom of expression than any other European state. Marx went to live in Brussels, where there was a sizable community of political exiles, including the man who converted him to socialism, Moses Hess.

Friedrich Engels helped to financially support Marx and his family. Engels gave Marx the royalties of his recently published book, Condition of the Working Class in England and arranged for other sympathizers to make donations. This enabled Marx the time to study and develop his economic and political theories. Marx spent his time trying to understand the workings of capitalist society, the factors governing the process of history and how the proletariat could help bring about a socialist revolution. (34)

In July 1845 Marx and Engels visited England. They spent most of the time consulting books in Manchester Library. Marx also visited London where he met the Chartist leaders, George Julian Harney and other political exiles from Europe. He praised Feargus O'Connor and wrote articles for the Northern Star and claimed it was "the only English paper worth reading for the continental democrats". (35)

Marx returned to Brussels and along with Engels finished their book, The German Ideology. It begins with one of Marx's attention-grabbing generalisations: "Hitherto men have always formed wrong ideas about themselves, about what they are and what they ought to be." He then went on to attack other German philosophers that he had previously praised. This included Ludwig Feuerbach, Bruno Bauer and Max Stirner. (36)

Marx and Engels spent 300 pages attacking Stirner's book, The Ego and Its Own (1845). As Richard Parry has pointed out: "Stirner saw all morality as an ideological justification for the repression of individuals; he opposed those revolutionaries who wished to set up a new morality in place of the old, as this would still result in the triumph of the collectivity over the individual and lay the basis for another despotic State. He denied that there was any real existence in concepts such as 'Natural Law', 'Common Humanity', 'Reason', 'Justice' or 'The People'; more than being simply absurd platitudes (which he derisively labelled sacred concepts, they were some of the whole gamut of abstract ideas which unfortunately dominated the thinking of most individuals... Stirner perceived the repressive nature of ideologies, even so-called revolutionary ones; he believed that all these sacred concepts manufactured by the intellect actually resulted in practical despotism." (37)

Marx and Engels completely rejected Stirner's idea that "heroic egoism and self-indulgence would liberate individuals from their imaginary oppression". It has been argued that the book reveals what Marx had learned from his philosophical and political adventures. Having rejected God, Hegel and Feuerbach in quick succession, he and Engels were now ready to unveil their own scheme of practical theory of theoretical practice - otherwise known as historical materialism". (38)

"The premises from which we begin are not arbitrary ones, not dogmas, but real premises from which abstraction can only be made in the imagination. They are the real individuals, their activity and the material conditions of their life... These premises can thus be verified in a purely empirical way... The division of labour inside a nation leads at first to the separation of industrial and commercial from agricultural labour, and hence to the separation of town and country and to the conflict of their interests. Its further development leads to the separation of commercial from industrial labour... The social structure and the state are continually evolving out of the life-process of definite individuals... It is not consciousness that determines life, but life that determines consciousness." (39)

Max Stirner had suggested that the division of labour applied only to those tasks which any reasonably trained person could perform. He used the example of the Italian artist, Raphael, as someone whose talent was such that no one else could have produced. This was an unfortunate example as Raphael had teams of assistants and pupils to complete his frescoes. Marx also pointed out that he did not believe that everyone should or not produce the work of a Raphael, but only a communist society would enable an artist to reach their full potential. (40)

"Stirner imagines that Raphael produced his pictures independently of the division of labour that existed in Rome at the time. If he were to compare Raphael with Leonardo da Vinci and Titian, he would see how greatly Raphael's works of art depended on the flourishing of Rome at that time, which occurred under Florentine influence, while the works of Leonardo depended on the state of things in Florence, and the works of Titian, at a later period, depended on the totally different development of Venice. Raphael as much as any other artist was determined by the technical advances in art made before him, by the organisation of society and the division of labour... In a communist society there are no painters but only people who engage in painting among other activities." (41)

The Communist Party Manifesto

In June 1847 Friedrich Engels produced a document called the Principles of Communism. It included the statement on what it meant to be a communist: "To organise society in such a way that every member of it can develop and use all his capabilities and powers in complete freedom and without thereby infringing the basic conditions of this society". He then goes on to explain how communism was to be achieved: "By the elimination of private property and its replacement by community of property." (42)

Karl Marx used this document as a first draft of the pamphlet entitled The Communist Manifesto. Marx finished the 12,000 word pamphlet in six weeks. Unlike most of Marx's work, it was an accessible account of communist ideology. Written for a mass audience, the book summarised the forthcoming revolution and the nature of the communist society that would be established by the proletariat. It has been claimed that it is the most widely read political pamphlet in human history. (43)

The pamphlet begins with the assertion: "The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles." Marx argued that if you are to understand human history you must not see it as the story of great individuals or the conflict between states. Instead, you must see it as the story of social classes and their struggles with each other. Marx explained that social classes had changed over time but in the 19th century the most important classes were the bourgeoisie and the proletariat. By the term bourgeoisie Marx meant the owners of the factories and the raw materials which are processed in them. The proletariat, on the other hand, own very little and are forced to sell their labour to the capitalists. (44)

Marx believed that these two classes are not merely different from each other, but also have different interests. He went on to argue that the conflict between these two classes would eventually lead to revolution and the triumph of the proletariat. With the disappearance of the bourgeoisie as a class, there would no longer be a class society. "Just as feudal society was burst asunder, bourgeois society will suffer the same fate." (45)

In November 1847 Marx made a visit to London. In a speech to a group of Chartists he argued: "The unification and brotherhood of nations is a phrase which is nowadays on the lips of all parties, particularly of the bourgeois free traders. A kind of brotherhood does indeed exist between the bourgeois classes of all nations. It is the brotherhood of the oppressors against the oppressed, of the exploiters against the exploited. Just as the bourgeois class of one country is united in brotherhood against the proletarians of that country, despite the competition and struggle of its members among themselves, so the bourgeoisie of all countries is united in brotherhood against the proletarians of all countries, despite their struggling and competing with each other on the world market."

Marx went on to say: "Of all countries it is England where the opposition between the proletariat and the bourgeoisie is most highly developed. Thus the victory of the English proletariat over the English bourgeoisie is of decisive importance for the victory of all oppressed peoples over their oppressors. Poland, therefore, must be freed, not in Poland, but in England. You Chartists should not express pious wishes for the liberation of nations. Defeat your own enemies at home and then you may be proudly conscious of having defeated the old social order in its entirety." (46)

Marx's main friend amongst the Chartists was Ernest Jones who had been born in Berlin but the family had returned to London where he became a lawyer. Jones was a follower of Feargus O'Connor, the leader of the Physical Force movement. Unlike most Chartists he was a revolutionary socialist. Marx accepted Jones as "the best and most advanced that England had to offer". Jones supplied Marx "with a great deal of information about English conditions". (47)

As the result of his research Marx became convinced that the revolution would first take place in Britain. Society was divided into "two radically dissimilar nations, as unlike as difference of race could make them." Gathered together in towns and cities but separated from the bourgeoisie. "The workers begin to feel as a class, as a whole: they begin to perceive that, though feeble as individuals, they form a power united." Through the growth of working-class political movements, led by people such as Robert Owen and John Doherty, "all the workers employed in manufacture are won for one form or the other of resistance to capital and bourgeoisie; and all are united upon this point, that they, as working-men... from a separate class, with separate interests and principles." (48)

The Communist Manifesto was published in Germany in February, 1848. Later that month a police spy in Belgium reported that: "This noxious pamphlet must indisputably exert the most corrupting influence upon the uneducated public at whom it is directed. The alluring theory of the dividing-up of wealth is held out to factory workers and day labourers as an innate right, and a profound hatred of the rulers and the rest of the community is inculcated into them. There would be a gloomy outlook for the fatherland and for civilisation if such activities succeeded in undermining religion and respect for the laws and in any great measure infected the lower class of the people." (49)

They were especially concerned by the fact that Marx had just received 6,000 gold francs as his share of his father's legacy and they suspected he was going to use this money to "finance the revolutionary movement". Jenny Marx later admitted: "The German workers in Brussels decided to arm themselves. Daggers, revolvers, etc., were procured. Karl willingly provided money, for he had just come into an inheritance." The couple were arrested and expelled from Belgium. (50)

Karl and Jenny Marx and their three children went to France who had just experienced a successful revolution. Within weeks, and on a temporary French passport, he was back in Cologne with Engels, who raised most of the money to found the daily Neue Rheinische Zeitung: Organ der Democratie. According to Eric Hobsbawm it was "the most coherent voice of the democratic left". (56) Engels claimed that he was not the most effective editor: "He is no journalist and will never become one. He pores for a whole day over a leading article that would take someone else a couple of hours as though it concerned the handling of a deep philosophical problem." (51)

On 21st March, 1848, Marx published a handbill headed "Demands of the Communist Party in Germany". The seventeen-point programme included only four of the ten points from the CMM - progressive income-tax, free schooling, state ownership of all means of transport and the creation of a national bank. One measure that was dropped was "abolition of all right of inheritance". Whereas the Manifesto had demanded the nationalisation of all land this was amended to "princely and other feudal estates". Other demands included universal adult suffrage and payment of salaries to parliamentary representatives. (52)

Marx fell out with Andreas Gottschalk, the leader of the Cologne Workers' Association and a representative of the Communist League in the German Constituent National Assembly. Gottschalk was a doctor who treated the poor and had a large following in the city. Whereas Marx's newspaper had a circulation of 5,000, the Cologne Workers' Association, had a membership of over 8,000 people. Marx condemned Gottschalk as a left-wing sectarian who had jeopardised the "united front" of bourgeoisie and proletariat by founding an exclusively working-class pressure group. When Gottschalk was arrested and charged with incitement to violence Marx refused to defend him: "We are reserving our judgement since we are all still lacking definite information about their arrest and the manner in which it was carried out... The workers will be sensible enough not to let themselves be provoked into creating a disturbance." (53)

Carl Schurz, a student, witnessed a meeting addressed by Karl Marx in August 1848. "He could not have been much more than thirty years old at that time, but he was already the recognised head of the advanced socialistic school... I have never seen a man whose bearing was so provoking and intolerable. To no opinion which differed from his own did he accord the honour of even condescending consideration. Everyone who contradicted him he treated with abject contempt; every argument that he did not like he answered either with biting scorn at the unfathomable ignorance that had prompted it, or with opprobrious aspersions upon the motives of him who had advanced it. I remember most distinctly the cutting disdain with which he pronounced the word 'bourgeoi''; and as a 'bourgeois' - that is, as a detestable example of the deepest mental and moral degeneracy - he denounced everyone who dared to oppose his opinion... It was very evident that not only had he not won any adherents, but had repelled many who otherwise might have become his followers." (54)

Marx warned that without a revolution in England the rebellion in Europe would end in failure: "The liberation of Europe is dependent on a successful uprising by the French working class. But every French social upheaval necessarily founders on the English bourgeoisie, on the industrial and commercial world-domination of Great Britain. England will only be overthrown by a world war, which is the only thing that could provide the Chartists, the organised party of the English workers, with the conditions for a successful rising against their gigantic oppressors." (55)

On 25th September, 1849, a state of martial law was declared in Cologne and the military commander immediately suspended publication of the Neue Rheinische Zeitung: Organ der Democratie. Marx now moved to Paris. He believed a socialist revolution was likely to take place in France at any time. However, within a month of arriving, the French police ordered him out of the capital. Only one country remained who would take him, England. He wrote to Friedrich Engels: "I count on this absolutely. You cannot stay in Switzerland. In London we shall get down to business." (56)

The Communist Manifesto was translated into English by Helen Macfarlane, a feminist Chartist who knew both Marx and Engels. George Julian Harney, a socialist leader of the Chartist movement, arranged for it to be published in his newspaper, Red Republican, in June 1850, with an editorial comment that it was the most revolutionary document ever published. (57)

Karl Marx in London

The Prussian authorities applied pressure on the British government to expel Marx but the Prime Minister, John Russell, held liberal views on freedom of expression and refused. At that time the country had the reputation for allowing political outcasts to live in London. Census figures show that 300,000 newcomers settled in the capital between 1841 and 1851, including several hundred political refugees.

With only the money that Engels could raise, the Marx family lived in extreme poverty. In March 1850 they were ejected from their two-roomed flat in Chelsea for failing to pay the rent. Jenny Marx explained in a letter to a friend, Joseph Weydemeyer: "Suddenly in came our landlady... and demanded the £5 we still owed her and, since this was not ready to hand... two bailiffs entered the house and placed under distrait what little I possessed - beds, linen, clothes, everything, even my poor infant's cradle, and the best of the toys belonging to the girls, who burst into tears." (58)

They found cheaper accommodation at 28 Dean Street, Soho, where they stayed for six years. Their fifth child, Franziska, was born at their new flat but she only lived for a year. Eleanor Marx was born in 1855 but later that year, Edgar became Jenny Marx's third child to die. Marx spent most of the time in the Reading Room of the British Museum, where he read the back numbers of The Economist and other books and journals that would help him analyze capitalist society. (59)

In order to help supply Marx with an income, Friedrich Engels decided to work at the Manchester office for his father's textile firm, Ermen & Engels. Jenny Marx wrote to him soon after he left: "My husband and all the rest of us have missed you sorely and have often longed to see you... However, I am very glad that you have left and are well on the way to becoming a great cotton lord." (60)

The two kept in constant contact and over the next twenty years they wrote to each other on average once every two days. Engels sent postal orders or £1 or £5 notes, cut in half and sent in separate envelopes. In this way the Marx family was able to survive. It has been estimated that on average Marx received £150 a year from Engels and other supporters. A sum on which a lower-middle-class family could live in some comfort. "The problem of the Marxian finances had been particularly intractable for two reasons: the Marxes felt it essential to maintain the public expenditure of a successful professional household, especially after their move into a middle-class district, and they were spectacularly bad at budgeting." (61)

The poverty of the Marx's family was confirmed by a Prussian police agent who visited the Dean Street flat in 1852. In his report he pointed out that the family had sold most of their possessions and that they did not own one "solid piece of furniture" and "though he is idle for days on end, he will work day and night with tireless endurance when he has a great deal of work to do." (62)

Jenny Marx helped her husband with his work and later wrote that "the memory of the days I spent in his little study copying his scrawled articles is among the happiest of my life." The only relief from the misery of poverty was on a Sunday when they went for family picnics on Hampstead Heath. On 14th April, 1852, shortly after her first birthday, Franziska died: "Only a couple of lines to let you know that our little child died this morning at a quarter past one." (63)

In 1852, Charles Dana, the socialist managing editor of the New York Daily Tribune, offered Marx the opportunity to write for his newspaper. Over the next ten years the newspaper published 487 articles by Marx (125 of them had actually been written by Engels). With a circulation of more than 200,000, the newspaper provide Marx with a large readership. "Its outlook was broadly progressive: in internal affairs it pursued an anti-slavery, free trade policy, while in foreign affairs it attacked the principle of autocracy, and so found itself in opposition to virtually every government in Europe." (64)

Another radical in the USA, George Ripley, commissioned Marx to write for the New American Cyclopaedia. Marx admitted that Engels was doing most of his writing: "Engels really has too much work, but being a veritable walking encyclopedia, he's capable, drunk or sober, of working at any hour of the day or night, is a fast writer and devilish quick on the uptake." (65)

With the money from Marx's journalism and the £120 inherited from Jenny's mother, the family were able to move to 9 Grafton Terrace, Kentish Town. In 1856 Jenny Marx, who was now aged 42, gave birth to a still-born child. Her health took a further blow when she contacted smallpox. Although she survived this serious illness, it left her deaf and badly scarred. Marx's health was also bad and he wrote to Engels claiming that "such a lousy life is not worth living". After a bad bout of boils in 1863, Marx told Engels that the only consolation was that "it was a truly proletarian disease" and "I hope the bourgeoisie will remember my carbuncles until their dying day." (66)

Marx published A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy in 1859. In the book Marx argued that the superstructure of law, politics, religion, art and philosophy was determined by economic forces. "It is not", he wrote, "the consciousness of men that determines their existence, but their social existence that determines their consciousness." This is what Friedrich Engels later called "false consciousness". (67)

Horace Greeley, the editor of the New York Daily Tribune, a supporter of democratic nationalism, found himself in growing disagreement with Marx's articles. The circulation of the newspaper went into decline and Greeley decided to dismiss most of his European correspondents. Charles Dana pleaded to be allowed to retain Marx, but in vain and in 1862 he was dismissed. (68)

This increased Marx's money problems. Engels sent him £5 a month but this failed to stop him getting deeply into debt. Ferdinand Lassalle, a wealthy socialist from Berlin also began sending money to Marx and offered him work as an editor of a planned new radical newspaper in Germany. Marx, unwilling to return to his homeland and rejected the job. Lassalle continued to send Marx money until he was killed in a duel on 28th August 1864. (69)

Das Kapital

Despite all his problems Marx continued to work on Das Kapital. On 2nd April 1867, Marx wrote to Engels pointing out that "I had resolved not to write to you until I could announce completion of the book, which is now the case". He added that "without you I would never have been able to bring the work to a conclusion, and I can assure you it always weighed like a nightmare on my conscience that you were allowing your fine energies to be squandered and to rust in commerce." (70)

The first volume of the book was published in September 1867. A detailed analysis of capitalism, the book dealt with important concepts such as surplus value (the notion that a worker receives only the exchange-value, not the use-value, of his labour); division of labour (where workers become a "mere appendage of the machine") and the industrial reserve army (the theory that capitalism creates unemployment as a means of keeping the workers in check). "The result was an original amalgam of economic theory, history, sociology and propaganda". (71)

Marx also deals with the issue of revolution. Marx argued that the laws of capitalism will bring about its destruction. Capitalist competition will lead to a diminishing number of monopoly capitalists, while at the same time, the misery and oppression of the proletariat would increase. Marx claimed that as a class, the proletariat will gradually become "disciplined, united and organised by the very mechanism of the process of capitalist production" and eventually will overthrow the system that is the cause of their suffering.

Paul Samuelson, one of the leading economists of the 20th century, has declared that Marx's theories can safely be ignored because the impoverishment of the workers "simply never took place". However, Francis Wheen argues that this view is based on a misreading of Marx's "General Law of Capitalist Accumulation" where he makes clear that he is "referring not to the pauperisation of the entire proletariat but to the 'lowest sediment' of society - the unemployed, the ragged, the sick, the old, the widows and orphans". The main point that Marx was making was that labour always "lags further and further behind capital, however many microwave ovens the workers can afford." (72)

Leszek Kolakowski, the Polish philosopher, supports Wheen when he tackles this issue in Main Currents of Marxism: Its Rise, Growth and Dissolution (1978): "It must be borne in mind that material pauperisation was not a necessary premiss either of Marx's analysis of the caused by wage labour, or of his prediction of the inescapable ruin of capitalism." (73)

Marx now began work on the second volume of Das Kapital. By 1871 his sixteen year old daughter, Eleanor Marx, was helping him with his work. Taught at home by her father, Eleanor already had a detailed understanding of the capitalist system and was to play an important role in the future of the British labour movement. On one occasion Marx told his children that "Jenny (his eldest daughter) is most like me, but Tussy (Eleanor) is me." (74)

Eleanor returned to the family home in 1881 to nurse her parents who were both very ill. Marx, who had a swollen liver, survived, but Jenny Marx died on 2nd December, 1881. Karl Marx was also devastated by the death of his eldest daughter in January 1883 from cancer of the bladder. Karl Marx died two months later on the 14th March, 1883.