Bloody Sunday

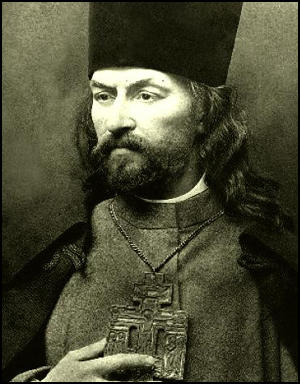

In 1902 Georgi Gapon became a priest in St. Petersburg where he showed considerable concern for the welfare of the poor. He soon developed a large following, "a handsome, bearded man, with a rich baritone voice, had oratorical gifts to a spell-binding degree". (1) The workers in St Petersburg had plenty to complain about. It was a time of great suffering for those on low incomes. About 40 per cent of houses had no running water or sewage. The Russian industrial employee worked on average an 11 hour day (10 hours on Saturday). Conditions in the factories were extremely harsh and little concern was shown for the workers' health and safety. Attempts by workers to form trade unions were resisted by the factory owners. In 1902 the army was called out 365 times to deal with unrest among workers. (2)

Vyacheslav Plehve, the Minister of the Interior, rejected all calls for reform. Lionel Kochan pointed out that "Plehve was the very embodiment of the government's policy of repression, contempt for public opinion, anti-semitism and bureaucratic tyranny" and it was no great surprise when Evno Azef, head of the Terrorist Brigade of the Socialist Revolutionary Party, ordered his assassination. (3)

On 28th July, 1904, Plehve was killed by a bomb thrown by Egor Sazonov on 28th July, 1904. Emile J. Dillon, who was working for the Daily Telegraph, witnessed the assassination: "Two men on bicycles glided past, followed by a closed carriage, which I recognized as that of the all-powerful minister (Vyacheslav Plehve). Suddenly the ground before me quivered, a tremendous sound as of thunder deafened me, the windows of the houses on both sides of the broad streets rattled, and the glass of the panes was hurled on to the stone pavements. A dead horse, a pool of blood, fragments of a carriage, and a hole in the ground were parts of my rapid impressions. My driver was on his knees devoutly praying and saying that the end of the world had come.... Plehve's end was received with semi-public rejoicings. I met nobody who regretted his assassination or condemned the authors." (4)

Plehve was replaced by Pyotr Sviatopolk-Mirsky, as Minister of the Interior. He held liberal views and hoped to use his power to create a more democratic system of government. Sviatopolk-Mirsky believed that Russia should grant the same rights enjoyed in more advanced countries in Europe. He recommended that the government strive to create a "stable and conservative element" among the workers by improving factory conditions and encouraging workers to buy their own homes. "It is common knowledge that nothing reinforces social order, providing it with stability, strength, and ability to withstand alien influences, better than small private owners, whose interests would suffer adversely from all disruptions of normal working conditions." (5)

Assembly of Russian Workers

In February, 1904, Sviatopolk-Mirsky's agents approached Father Georgi Gapon and encouraged him to use his popular following to "direct their grievances into the path of economic reform and away from political discontent". (6) Gapon agreed and on 11th April 1904 he formed the Assembly of Russian Workers of St Petersburg. Its aims were to affirm "national consciousness" amongst the workers, develop "sensible views" regarding their rights and foster amongst the members of the union "activity facilitating the legal improvements of the workers' conditions of work and living". (7)

By the end of 1904 the Assembly had cells in most of the larger factories, including a particularly strong contingent at the Putilov works. The overall membership has been variously estimated between 2,000 and 8,000. Whatever the true figure, the strength of the Assembly and of its sympathizers exceeded by far that of the political parties. For example, in St Petersburg at this time, the local Menshevik and Bolshevik groups could muster no more than 300 members each. (8)

If you find this article useful, please feel free to share on websites like Reddit. Please visit our support page. You can follow John Simkin on Twitter, Google+ & Facebook or subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

Adam B. Ulam, the author of The Bolsheviks (1998) was highly critical of the leader of the Assembly of Russian Revolution: "Gapon had certain peasant cunning, but was politically illiterate, and his personal tastes were rather inappropriate for either a revolutionary or a priest: he was unusually fond of gambling and drinking. Yet he became an object of a spirited competition among various branches of the radical movement." (9) Another revolutionary figure, Victor Serge, saw him in a much more positive light. "Gapon is a remarkable character. He seems to have believed sincerely in the possibility of reconciling the true interests of the workers with the authorities' good intentions". (10)

According to Cathy Porter: "Despite its opposition to equal pay for women, the Union attracted some three hundred women members, who had to fight a great deal of prejudice from the men to join." Vera Karelina was an early member and led its women's section: "I remember what I had to put up with when there was the question of women joining... There wasn't a single mention of the woman worker, as if she was non-existent, like some sort of appendage, despite the fact that the workers in several factories were exclusively women." Karelina was also a Bolshevik but complained "how little our party concerned itself with the fate of working women, and how inadequate was its interest in their liberation.'' (11)

Adam B. Ulam claimed that the Assembly of Russian Workers of St Petersburg was firmly under the control of the Minister of the Interior: "Father Gapon... had, with the encouragement and subsidies of the police, organized a workers' union, thus continuing the work of Zubatov. The union had scrupulously excluded Socialists and Jews. For a while the police could congratulate themselves on their enterprise." (12) David Shub, a Menshevik, agreed, claiming that the organisation had been set up to "wean the workers away from radicalism". (13)

Alexandra Kollontai, an important Bolshevik leader, did join the union with little difficulty. She was also a feminist and felt the Bolsheviks had not done enough to support the demands of women members. Kollontai believed that any organisation that allowed factory women was preferable to the Bolsheviks' almost total silence about them, and "how little our party concerned itself with the fate of working women, and how inadequate was its interest in their liberation." (14)

1904 was a bad year for Russian workers. Prices of essential goods rose so quickly that real wages declined by 20 per cent. When four members of the Assembly of Russian Workers were dismissed at the Putilov Iron Works in December, Gapon tried to intercede for the men who lost their jobs. This included talks with the factory owners and the governor-general of St Petersburg. When this failed, Gapon called for his members in the Putilov Iron Works to come out on strike. (15)

Father Georgi Gapon demanded: (i) An 8-hour day and freedom to organize trade unions. (ii) Improved working conditions, free medical aid, higher wages for women workers. (iii) Elections to be held for a constituent assembly by universal, equal and secret suffrage. (iv) Freedom of speech, press, association and religion. (v) An end to the war with Japan. By the 3rd January 1905, all 13,000 workers at Putilov were on strike, the department of police reported to the Minister of the Interior. "Soon the only occupants of the factory were two agents of the secret police". (16)

The strike spread to other factories. By the 8th January over 110,000 workers in St. Petersburg were on strike. Father Gapon wrote that: "St Petersburg seethed with excitement. All the factories, mills and workshops gradually stopped working, till at last not one chimney remained smoking in the great industrial district... Thousands of men and women gathered incessantly before the premises of the branches of the Workmen's Association." (17)

Tsar Nicholas II became concerned about these events and wrote in his diary: "Since yesterday all the factories and workshops in St. Petersburg have been on strike. Troops have been brought in from the surroundings to strengthen the garrison. The workers have conducted themselves calmly hitherto. Their number is estimated at 120,000. At the head of the workers' union some priest - socialist Gapon. Mirsky (the Minister of the Interior) came in the evening with a report of the measures taken." (18)

Gapon drew up a petition that he intended to present a message to Nicholas II: "We workers, our children, our wives and our old, helpless parents have come, Lord, to seek truth and protection from you. We are impoverished and oppressed, unbearable work is imposed on us, we are despised and not recognized as human beings. We are treated as slaves, who must bear their fate and be silent. We have suffered terrible things, but we are pressed ever deeper into the abyss of poverty, ignorance and lack of rights." (19)

The petition contained a series of political and economic demands that "would overcome the ignorance and legal oppression of the Russian people". This included demands for universal and compulsory education, freedom of the press, association and conscience, the liberation of political prisoners, separation of church and state, replacement of indirect taxation by a progressive income tax, equality before the law, the abolition of redemption payments, cheap credit and the transfer of the land to the people. (20)

Bloody Sunday

Over 150,000 people signed the document and on 22nd January, 1905, Father Georgi Gapon led a large procession of workers to the Winter Palace in order to present the petition. The loyal character of the demonstration was stressed by the many church icons and portraits of the Tsar carried by the demonstrators. Alexandra Kollontai was on the march and her biographer, Cathy Porter, has described what took place: "She described the hot sun on the snow that Sunday morning, as she joined hundreds of thousands of workers, dressed in their Sunday best and accompanied by elderly relatives and children. They moved off in respectful silence towards the Winter Palace, and stood in the snow for two hours, holding their banners, icons and portraits of the Tsar, waiting for him to appear." (21)

Harold Williams, a journalist working for the Manchester Guardian, also watched the Gapon led procession taking place: "I shall never forget that Sunday in January 1905 when, from the outskirts of the city, from the factory regions beyond the Moscow Gate, from the Narva side, from up the river, the workmen came in thousands crowding into the centre to seek from the tsar redress for obscurely felt grievances; how they surged over the snow, a black thronging mass." (22)

The soldiers machine-gunned them down and the Cossacks charged them. (23) Alexandra Kollontai observed the "trusting expectant faces, the fateful signal of the troops stationed around the Palace, the pools of blood on the snow, the bellowing of the gendarmes, the dead, the wounded, the children shot." She added that what the Tsar did not realise was that "on that day he had killed something even greater, he had killed superstition, and the workers' faith that they could ever achieve justice from him. From then on everything was different and new." (24) It is not known the actual numbers killed but a public commission of lawyers after the event estimated that approximately 150 people lost their lives and around 200 were wounded. (25)

Gapon later described what happened in his book The Story of My Life (1905): "The procession moved in a compact mass. In front of me were my two bodyguards and a yellow fellow with dark eyes from whose face his hard labouring life had not wiped away the light of youthful gaiety. On the flanks of the crowd ran the children. Some of the women insisted on walking in the first rows, in order, as they said, to protect me with their bodies, and force had to be used to remove them. Suddenly the company of Cossacks galloped rapidly towards us with drawn swords. So, then, it was to be a massacre after all! There was no time for consideration, for making plans, or giving orders. A cry of alarm arose as the Cossacks came down upon us. Our front ranks broke before them, opening to right and left, and down the lane the soldiers drove their horses, striking on both sides. I saw the swords lifted and falling, the men, women and children dropping to the earth like logs of wood, while moans, curses and shouts filled the air." (26)

Alexandra Kollontai observed the "trusting expectant faces, the fateful signal of the troops stationed around the Palace, the pools of blood on the snow, the bellowing of the gendarmes, the dead, the wounded, the children shot." She added that what the Tsar did not realise was that "on that day he had killed something even greater, he had killed superstition, and the workers' faith that they could ever achieve justice from him. From then on everything was different and new." (27) It is not known the actual numbers killed but a public commission of lawyers after the event estimated that approximately 150 people lost their lives and around 200 were wounded. (28)

Father Gapon escaped uninjured from the scene and sought refuge at the home of Maxim Gorky: "Gapon by some miracle remained alive, he is in my house asleep. He now says there is no Tsar anymore, no church, no God. This is a man who has great influence upon the workers of the Putilov works. He has the following of close to 10,000 men who believe in him as a saint. He will lead the workers on the true path." (29)

Aftermath

The killing of the demonstrators became known as Bloody Sunday and it has been argued that this event signalled the start of the 1905 Revolution. That night the Tsar wrote in his diary: "A painful day. There have been serious disorders in St. Petersburg because workmen wanted to come up to the Winter Palace. Troops had to open fire in several places in the city; there were many killed and wounded. God, how painful and sad." (30)

The massacre of an unarmed crowd undermined the standing of the autocracy in Russia. The United States consul in Odessa reported: "All classes condemn the authorities and more particularly the Tsar. The present ruler has lost absolutely the affection of the Russian people, and whatever the future may have in store for the dynasty, the present tsar will never again be safe in the midst of his people." (31)

The day after the massacre all the workers at the capital's electricity stations came out on strike. This was followed by general strikes taking place in Moscow, Vilno, Kovno, Riga, Revel and Kiev. Other strikes broke out all over the country. Pyotr Sviatopolk-Mirsky resigned his post as Minister of the Interior, and on 19th January, 1905, Tsar Nicholas II summoned a group of workers to the Winter Palace and instructed them to elect delegates to his new Shidlovsky Commission, which promised to deal with some of their grievances. (32)

Lenin, who had been highly suspicious of Father Gapon, admitted that the formation of Assembly of Russian Workers of St Petersburg and the occurrence of Bloody Sunday, had made an important contribution to the development of a radical political consciousness: "The revolutionary education of the proletariat made more progress in one day than it could have made in months and years of drab, humdrum, wretched existence." (33)

Henry Nevinson, of The Daily Chronicle commented that Gapon was "the man who struck the first blow at the heart of tyranny and made the old monster sprawl." When he heard the news of Bloody Sunday Leon Trotsky decided to return to Russia. He realised that Father Gapon had shown the way forward: "Now no one can deny that the general strike is the most important means of fighting. The twenty-second of January was the first political strike, even if he was disguised under a priest's cloak. One need only add that revolution in Russia may place a democratic workers' government in power." (34)

Trotsky believed that Bloody Sunday made the revolution much more likely. One revolutionary noted that the killing of peaceful protestors had changed the political views of many peasants: "Now tens of thousands of revolutionary pamphlets were swallowed up without remainder; nine-tenths were not only read but read until they fell apart. The newspaper which was recently considered by the broad popular masses, and particularly by the peasantry, as a landlord's affair, and when it came accidentally into their hands was used in the best of cases to roll cigarettes in, was now carefully, even lovingly, straightened and smoothed out, and given to the literate." (35)

After the massacre Georgi Gapon left Russia and went to live in Geneva. Bloody Sunday made Father Gapon a national figure overnight and he enjoyed greater popularity "than any Russian revolutionary had previously commanded". (38) Gapon announced that he had abandoned his ideas of liberal reforms and had joined the Socialist Revolutionary Party (SRP). He also had meetings with Lenin, Peter Kropotkin, George Plekhanov and Rudolf Rocker. Lenin was disappointed that Gapon had joined the SRP and told him that he hoped he would "work to obtain that clarity of revolutionary outlook necessary for a political leader." (36)

Victor Adler sent Trotsky a telegram after receiving a message from Pavel Axelrod. "I have just received a telegram from Axelrod saying that Gapon has arrived abroad and announced himself as a revolutionary. It's a pity. If he had disappeared altogether there would have remained a beautiful legend, whereas as an emigre he will be a comical figure. You know, such men are better as historical martyrs than as comrades in a party." (37)

It was important for the authorities to discredit Gapon and stories were leaked about his contacts with the Minister of the Interior. A member of the SRP, Pinchas Rutenberg, informed Victor Chernov, Evno Azef and Boris Savinkov that Gapon was spying on Russian revolutionaries in exile. It was suggested that Gapon should be murdered. Chernov rejected this idea and pointed out that he was still revered by ordinary workers, and that if he was murdered the SRP would be accused of killing him over political differences. (38)

Azef disagreed with this view and gave orders to Rutenberg to kill Gapon. On 26th March 1906, Gapon arrived to meet Rutenberg in a rented cottage in Ozerki, a little town north of St. Petersburg, and after a month he was found there with his hands tied, hanging from a coat hook on the wall. (39)

Primary Sources

(1) George Gapon, letter to Nicholas II (21st January, 1905)

The people believe in thee. They have made up their minds to gather at the Winter Palace tomorrow at 2 p.m. to lay their needs before thee. Do not fear anything. Stand tomorrow before the party and accept our humblest petition. I, the representative of the workingmen, and my comrades, guarantee the inviolability of thy person.

(2) Extract from the petition that George Gapon hoped to present to Nicholas II on 22nd January, 1905.

We workers, our children, our wives and our old, helpless parents have come, Lord, to seek truth and protection from you. We are impoverished and oppressed, unbearable work is imposed on us, we are despised and not recognized as human beings. We are treated as slaves, who must bear their fate and be silent. We have suffered terrible things, but we are pressed ever deeper into the abyss of poverty, ignorance and lack of rights.

(3) The demands made by George Gapon and the Assembly of Factory Workers.

(1) An 8-hour day and freedom to organize trade unions.

(2) Improved working conditions, free medical aid, higher wages for women workers.

(3) Elections to be held for a constituent assembly by universal, equal and secret suffrage.

(4) Freedom of speech, press, association and religion.

(5) An end to the war with Japan.

(4) Nicholas II, diary entry (21st January, 1917)

There was much activity and many reports. Fredericks came to lunch. Went for a long walk. Since yesterday all the factories and workshops in St. Petersburg have been on strike. Troops have been brought in from the surroundings to strengthen the garrison. The workers have conducted themselves calmly hitherto. Their number is estimated at 120,000. At the head of the workers' union some priest - socialist Gapon. Mirsky came in the evening with a report of the measures taken.

(5) George Gapon, The Story of My Life (1905)

The procession moved in a compact mass. In front of me were my two bodyguards and a yellow fellow with dark eyes from whose face his hard labouring life had not wiped away the light of youthful gaiety. On the flanks of the crowd ran the children. Some of the women insisted on walking in the first rows, in order, as they said, to protect me with their bodies, and force had to be used to remove them.

Suddenly the company of Cossacks galloped rapidly towards us with drawn swords. So, then, it was to be a massacre after all! There was no time for consideration, for making plans, or giving orders. A cry of alarm arose as the Cossacks came down upon us. Our front ranks broke before them, opening to right and left, and down the lane the soldiers drove their horses, striking on both sides. I saw the swords lifted and falling, the men, women and children dropping to the earth like logs of wood, while moans, curses and shouts filled the air.

Again we started forward, with solemn resolution and rising rage in our hearts. The Cossacks turned their horses and began to cut their way through the crowd from the rear. They passed through the whole column and galloped back towards the Narva Gate, where - the infantry having opened their ranks and let them through - they again formed lines.

We were not more than thirty yards from the soldiers, being separated from them only by the bridge over the Tarakanovskii Canal, which here masks the border of the city, when suddenly, without any warning and without a moment's delay, was heard the dry crack of many rifle-shots. Vasiliev, with whom I was walking hand in hand, suddenly left hold of my arm and sank upon the snow. One of the workmen who carried the banners fell also. Immediately one of the two police officers shouted out "What are you doing? How dare you fire upon the portrait of the Tsar?"

An old man named Lavrentiev, who was carrying the Tsar's portrait, had been one of the first victims. Another old man caught the portrait as it fell from his hands and carried it till he too was killed by the next volley. With his last gasp the old man said "I may die, but I will see the Tsar".

Both the blacksmiths who had guarded me were killed, as well as all these who were carrying the ikons and banners; and all these emblems now lay scattered on the snow. The soldiers were actually shooting into the courtyards at the adjoining houses, where the crowd tried to find refuge and, as I learned afterwards, bullets even struck persons inside, through the windows.

At last the firing ceased. I stood up with a few others who remained uninjured and looked down at the bodies that lay prostrate around me. Horror crept into my heart. The thought flashed through my mind, And this is the work of our Little Father, the Tsar". Perhaps the anger saved me, for now I knew in very truth that a new chapter was opened in the book of history of our people.

(6) Nicholas II, diary entry (22nd January, 1917)

A painful day. There have been serious disorders in St. Petersburg because workmen wanted to come up to the Winter Palace. Troops had to open fire in several places in the city; there were many killed and wounded. God, how painful and sad.

(7) Alexandra Kollontai was one of those who witnessed Bloody Sunday.

Bloody Sunday, 1905, found me in the street. I was going with the demonstrators to the Winter Palace, and the picture of the massacre of unarmed, working folk is for ever imprinted on my memory. The unusual bright January sunshine, trusting, expectant faces, the fateful signal from the troops drawn up round the palace, pools of blood on the white snow, the whips, the whooping of the gendarmes, the dead, the injured, children shot.

(8) Maxim Gorky was one of those who took part in the march to the Winter Palace. That night Gapon took refuge in Gorky's house.

Gapon by some miracle remained alive, he is in my house asleep. He now says there is no Tsar anymore, no church, no God. This is a man who has great influence upon the workers of the Putilov works. He has the following of close to 10,000 men who believe in him as a saint. He will lead the workers on the true path.

(9) Bernard Pares, The Fall of the Russian Monarchy (2001)

Gapon's organization was based on a representation of one person for every thousand workers. He planned a peaceful demonstration in the form of a march to the Winter Palace, carrying church banners and singing religious and national songs. Owing to the idiocy of the military authorities, the crowd was met with rifle fire both at the outskirts of the city and the palace square. The actual victims, as certified by a public commission of lawyers of the Opposition, was approximately 150 killed and 200 wounded; and as all who had taken a leading part in the procession were then expelled from the capital, the news was circulated all over the Empire.

Student Activities

The Outbreak of the General Strike (Answer Commentary)

The 1926 General Strike and the Defeat of the Miners (Answer Commentary)

The Coal Industry: 1600-1925 (Answer Commentary)

Women in the Coalmines (Answer Commentary)

Child Labour in the Collieries (Answer Commentary)

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

1832 Reform Act and the House of Lords (Answer Commentary)

The Chartists (Answer Commentary)

Women and the Chartist Movement (Answer Commentary)

Benjamin Disraeli and the 1867 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

William Gladstone and the 1884 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Canal Mania (Answer Commentary)

Early Development of the Railways (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)

The Luddites: 1775-1825 (Answer Commentary)

The Plight of the Handloom Weavers (Answer Commentary)

Health Problems in Industrial Towns (Answer Commentary)

Public Health Reform in the 19th century (Answer Commentary)

Walter Tull: Britain's First Black Officer (Answer Commentary)

Football and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

Football on the Western Front (Answer Commentary)

Käthe Kollwitz: German Artist in the First World War (Answer Commentary)

American Artists and the First World War (Answer Commentary)