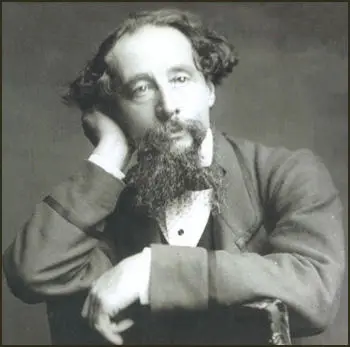

Charles Dickens

Charles Allston Collins, the artist brother of Wilkie Collins, wanted to marry Kate Dickens. At first Charles Dickens refused permission because he disapproved of Wilkie living with Caroline Graves, a shop girl who had an illegitimate child. Kate was also unsure but as she later recalled, that he had left her mother, Catherine Dickens, after beginning a relationship with Nellie Ternan: "My father was like a madman... This affair brought out all that was worst - all that was weakest in him. He did not care a damn what happened to any of us. Nothing could surpass the misery and unhappiness of our home."

Eventually he agreed to Kate's marriage. He wrote to his friend, W.W. F. de Cerjat, about his thoughts on the matter: "My second daughter (Kate) is going to be married in the course of the summer, to the brother of Wilkie Collins the novelist. He was bred an artist (the father was one of the most famous painters of English green lanes and coast pieces), and was attaining considerable distinction, when he turned indifferent to it and fell back upon that worst of cushions, a small independence. He is a writer too, and does the Eye Witness in All The Year Round. He is a gentleman, and accomplished.... I do not doubt that the young lady might have done much better, but there is no question that she is very fond of him, and that they have come together by strong attraction. Therefore the undersigned venerable parent says no more, and takes the goods the Gods provide him."

Charles Allston Collins married Kate Dickens on 17th July 1860, at Gad's Hill Place. Dickens's biographer, Claire Tomalin , has pointed out: "Kate married Wilkie's brother, Charles Collins, thirty-two to her twenty, a good-natured man but a semi-invalid, who was giving up art to try to write. Dickens blamed himself for Kate's decision, knowing she was marrying without love and to get away from home, but he put on a showy wedding at Gad's." That evening Mamie Dickens found her father weeping into her sister's wedding dress, and he told her how much he blamed himself for the marriage.

In September 1860 Dickens burnt thousands of letters accumulated over the last 20 years on a bonfire at Gad's Hill Place . Three of his children brought out basketful after basketful of them. Mamie asked him to keep some of them, but he refused. Eleven-year-old Henry remembers roasting onions in the hot ashes of the fire. Dickens also wrote to all his friends asking them to destroy all the letters they had sent to him over the years. It was almost some kind of hatred of the past. When Angela Burdett-Coutts suggested that Dickens should meet again with Catherine Dickens, after the death of their son, Walter, he replied that “a page in my life which once had writing on it, has become absolutely blank, and that it is not in my power to pretend that it has a solitary word upon it.”

Dickens wrote to William Henry Wills on 4th September: "Yesterday I burnt, in the field at Gad's Hill, the accumulated letters and papers of twenty years. They sent up a smoke like the Genie when he got out of the casket on the seashore, and as it was an exquisite day when I began, and rained very heavily when I finished. I suspect my correspondence of having overcast the face of the Heavens." It is believed that Dickens also destroyed details of all his interviews he carried out with the young women at Urania Cottage during this bonfire. Paul Lewis, the author of Burning the Evidence , that appeared in The Dickensian (Winter, 2004), has described it as "probably the most valuable bonfire on record."

Less that three months after the bonfire at Gad's Hill Place Dickens wrote to his friend William Charles Macready: "Daily seeing improper uses made of confidential letters in the addressing of them to a public audience that have no business with them, I made not long ago a great fire in my field at Gad's Hill, and burnt every letter I possessed. And now I always destroy every letter I receive not on absolute business, and my mind is so far at ease."

Peter Ackroyd has argued that it was significant that three weeks later he began work on Great Expectations , a novel in "which he is engaged in exorcising, the influence of the past by rewriting it". The story was placed in the period of his own childhood and youth and set in home territory of Rochester and Romney Marsh. Dickens admitted that while he was writing the novel he suffered from "neuralgic pains in the face" that vanished the moment he had written the last word of the story.

Dickens wrote to John Forster that he had the idea for the novel while writing an essay for his proposed, Uncommercial Traveller. "Such a very fine, new, and grotesque idea has opened upon me, that I begin to doubt whether I had not better cancel the little paper, and reserve the notion for a new book." Later he told Forster that the idea "was the germ of Pip and Magwitch which at first he intended to make the ground work of a tale in the old twenty-number format... The name is Great Expectations." It has been pointed out that "in all his previous novels in which an innocent provincial boy or youth comes to London to seek his fortune the book is named after the boy or youth" but in Great Expectations "reaches for more... suggesting the fantasies not just of an individual but of a whole society, or at least of a generation".

The narrator of the story is Philip Pirrip (Pip), an orphan who is apprenticed to Joe Gargery, a blacksmith. The novel begins with Pip being frightened in a churchyard on Romney Marsh by a man with a great iron on his leg, who is clearly an escaped convict. The man, Abel Magwitch, persuades Pip to bring him a file and some food. This enables Magwitch to remove his fetters and escape from the area.

As a boy Pip meets Miss Havisham. In her youth she had been a beautiful heiress and had been engaged to a man called Compeyson. However, on the day of her wedding, she receives a letter from him breaking off the relationship. Havisham is devastated by the news and after stopping all the clocks at twenty minutes to nine - the time of her receiving the letter - she decides never to leave the house. Havisham adopts a beautiful orphan girl (Estella) and educates her to steel her heart against all tenderness and to lead young men to love her so that she may break their hearts. Pip falls in love with Estella but she treats him very badly.

Dickens explained to Forster: "The work will be written in the first person throughout, and... you will find the hero to be a boy-child, like David Copperfield. Then he will be an apprentice. You will not have to complain of the want of humour as in The Tale of Two Cities. I have made the opening, I hope, in general effect exceedingly droll. I have put a child and a good-natured foolish man in relations that seem to me very funny. Of course I have got in the pivot on which the story will turn too - and which indeed, as you will remember, was the grotesque tragic-comic conception that first encouraged me. To be quite sure I had fallen into no unconscious repetitions, I read David Copperfield again the other day, and was affected by it to a degree you would hardly believe."

The magazine, Harper's Weekly, agreed to pay £1,250 for the right to serialise the novel in the United States. This was £250 more than he received for A Tale of Two Cities. It was also decided that the first installment of Great Expectations appeared in All the Year Round on 1st December, 1860. The readers appeared to like the new novel. Dickens wrote to William Macready and explained that it was an "immediate success". He added it "seems universally liked - I suppose because it opens funnily and with an interest too".

Dickens later introduces Mr Jaggers into the story. He is a criminal lawyer who is employed by a man who wants to provide Pip with financial security. Jaggers tells Pip that he will act as his guardian until he comes into full possession of his fortune. On reaching the age of 21 years of age, Jaggers presents him with £500 from his unknown benefactor. Elated by his good fortune, he looks down upon the friends of his early days. Pip now expects to marry Estella, but she still treats him coldly.

Pip eventually discovers that his benefactor is Abel Magwitch. He has made his fortune in sheep-farming in New South Wales. Magwitch travels back to England to meet Pip. While he is in London he is recaptured and later dies in prison. Pip's situation is made worse by Estella marrying Bentley Drummle, who has nothing to recommend him but money.

Some critics have argued that Estella is based on Ellen Ternan. However, others, such as Michael Slater, believe that the model for the character is much more likely to have been Maria Beadnell. "There has been a general assumption since the revelations about his relationship with Nelly Ternan that Pip's anguished love for the heartless Estella reflects Dickens's passion for a cold and unresponsive Nelly. But, as will have become abundantly clear, we have very little evidence as to what Dickens and Nelly's relations actually were at the time... To me, it has always seemed more likely, in fact, that in this novel of sadly chasened retrospection, Dickens's depiction of the young adult Pip's sufferings at the hands of Estella owes more to memories of those now distant years of tormenting enslavement to Marie Beadnell that he had earlier turned to such favour and such prettiness when writing David Copperfield."

Dickens respected the opinion of fellow novelist Edward Bulwer-Lytton and submitted the last few chapters of Great Expectations for him to read in the summer of 1861. Bulwer-Lytton claimed that the public would not like the sad ending in the book and urged Dickens to change it in order for Pip to end up with Estella. Dickens accepted Bulwer-Lytton's advice and rewrote the ending so Bentley Drummle dies and therefore enables Estella to marry Pip.

Dickens wrote to John Forster on 1st July 1860: "You will be surprised to hear that I have changed the end of Great Expectations from and after Pip's return to Joe's, and finding his little likeness there. Bulwer, who has been, as I think you know, extraordinary taken by the book, so strongly urged it upon me, after reading the proofs, and supported his views with such good reasons, that I resolved to make the change... I have put in as pretty a little piece of writing as I could, and I have no doubt the story will be more acceptable through the alteration."

Forster, felt the original ending was "more consistent with the draft, as well as the natural working out of the tale." As one critic has pointed out that the original ending "resonated perfectly with this novel of ruined lives and lost illusions, and substituted it for an ending in which, apparently, boy finally gets girl and they live happily ever after." George Bernard Shaw agreed, arguing that the novel "is too serious a book to be a trivially happy one. Its beginning is unhappy; its middle is unhappy; and the conventional happy ending is an outrage on it."

The last instalment appeared in All the Year Round on 3rd August 1861. The majority of critics did not like the book. Blackwood’s Magazine found Great Expectations "feeble, fatigued, colourless", whereas Dublin University Magazine argued that it was evidence of "the growing weakness of a once mighty genius." However, The Saturday Review praised the book as "new, original, powerful, and very entertaining." Eneas Sweetland Dallas in The Times argued that "Dickens has in the present work given us more of his earlier fancies than we have had for years."

Charles Culliford Dickens worked in Hong Kong as a tea buyer. He also visited Walter Landor Dickens in Calcutta before returning to London in February 1861, in order to marry Bessie Evans (1839–1907). This caused another conflict with his father as Bessie was the daughter of Frederick Mullet Evans, Dickens's former publisher who had supported Catherine during the marriage separation. Dickens vowed never to speak to Evans again, and attempted to sever all contact between the two families. He told Catherine: "I absolutely prohibit... any of the children... ever being taken to Mr. Evans's house".

In March 1861, Dickens commented: "Charley.... will probably marry the daughter of Mr. Evans, the very last person on earth whom I could desire so to honor me." He blamed Catherine for his son's "odious" choice. "I wish I could hope that Charley's marriage may not be a disastrous one. There is no help for it, and the dear fellow does what is unavoidable - his foolish mother would have effectually committed him if nothing else had; chiefly I suppose because her hatred of the bride and all belonging to her, used to know no bounds, and was quite inappeasable. But I have a strong belief, founded on careful observation of him, that he cares nothing for the girl".

Claire Tomalin, the author of Dickens: A Life (2011) has pointed out: "He (Charles Dickens) tried to stop friends from attending the wedding, or entering the Evans house; and he blamed Catherine, who was of course at the wedding, and was indeed fond of the bride." The couple were married at St. Mark's Church in Regent's Park, on 19th November 1861. Dickens wrote to Robert Bulwer-Lytton complaining: ""The name the young lady has changed for mine, is odious to me and when I have said that. I have said all that need be said". Bessie gave birth to Mary Angela Dickens in autumn 1862.

According to Henry Fielding Dickens, his brother Francis Jeffrey Dickens was the most intelligent of the children: "Frank, whom I always considered the cleverest and best read of all of us, in spite of a very quick temper and strange oddities of manner." Arthur A. Adrian has argued: "Interested in becoming a doctor, he had been sent to Hamburg to learn German. But discouraged by his stammer, he had soon abandoned all ambitions for a professional career and aspired instead to be a gentleman farmer in Africa, Canada, or Australia." His father rejected this proposal and insisted he joined the Foreign Office. However, he failed the examination. Dickens found his failure "unaccountable" and applied to Henry Brougham to get him into a place in the Registrar's Office in London. When this was unsuccessful, Dickens arranged for him to join the Bengal Mounted Police in India. He left the country in December 1863.

While in India Dickens's son, Walter Landor Dickens, got in debt. Dickens was very angry with him when he heard the news and refused to send him money to solve the problem. Walter wrote to Mamie Dickens that he was very ill. Arrangements were made to send him home. The family were later informed that on 31st December, 1863: "He was talking with other patients in the hospital and became rather excited about the arrangements he proposed for his homeward passage, when a violent fit of coughing came on and the Aneurism burst into the left bronchial tube and life became extinct in a few seconds by the rush of blood which poured from his mouth." He was buried in the Bhowanipore Cemetery, Calcutta . Dickens wrote to Angela Burdett Coutts : "I could have wished it had pleased God to let him see his home again, but I think he would have died at the door."

Arthur A. Adrian, the author of Georgina Hogarth and the Dickens Circle (1957) has pointed out: "A few months later arrived the all too familiar evidence of reckless spending - Walter's unpaid accounts... Among his possessions Walter had left nothing of value: only a small trunk, changes of linen, some prayer books, and a coloured photograph of a woman believed to be a member of the family. (It may have been his Aunt Georgy's recently taken portrait. There would have been time for it to reach him before his death.) According to his captain, everything else had been turned into cash in preparation for the return to England. What could Walter have done with his money! The officers' mess, the regimental store, the billiard table, the native servants, a merchant or two - all remained to be paid. The claims against him, not including the servants' wages for £39, were in excess of £100."

William Hardman, editor of The Morning Post, wrote to a friend: "Poor Mrs. Charles Dickens is in great grief at the loss of her second son, Walter Landor Dickens, who has died with his regiment in India... Her grief is much enhanced by the fact that her husband has not taken any notice of the event to her, either by letter or otherwise. If anything were wanting to sink Charles Dickens to the lowest depths in my esteem, this fills up the measure of his iniquity. As a writer, I admire him: as a man, I despise him."

In November 1863, Dickens and William Makepeace Thackeray spoke together for the first time since the break with Catherine. According to Dickens he saw Thackeray hanging up his hat in the Athenaeum Club and said to him: "Thackeray, have you been ill." Another witness, Sir Theodore Martin gives a different account of the meeting. He was with Thackeray when Dickens passed close by "without making any sign of recognition". Martin claims that Thackeray broke off his conversation with him to call out to Dickens. "Dickens turned to him, and I saw Thackeray speak and presently hold out his hand to Dickens. They shook hands, a few words were exchanged, and immediately Thackeray returned to me saying I'm glad I have done this."

Between 1862 and 1865 there is no evidence that Ellen Ternan lived in England. She did not even attend her sister's wedding. We do know that Charles Dickens spent a lot of time during this period travelling between London and Paris. Dickens wrote to a friend, William de Cerjat: "Being on the Dover line, and my being very fond of France, occasion me to cross the channel perpetually.... away I go by the mail-train, and turn up in Paris or anywhere else that suits my humour, next morning. So I come back as fresh as a daisy."

The author of The Invisible Woman: The Story of Nelly Ternan and Charles Dickens (1991) has suggested that the reason for this was that Paris was the temporary home of Ternan. Another researcher, Robert R. Garnett, the author of Charles Dickens in Love (2012), believes Ternan gave birth to Dickens's child in late January to early February 1863. Garnett suggests the baby died a few weeks later. This story is supported by the testimony of two of his children, Kate Dickens Perugini and Henry Fielding Dickens. This information appeared in Dickens and Daughter (1939), a book written by Gladys Storey. Supporters of Dickens attacked the book as being unreliable, especially the passages about Ternan and the birth of a child. However, George Bernard Shaw, wrote to The Times Literary Supplement to say that Kate had told him everything in the book forty years before." Henry claimed that Ellen was taken to France when she became pregnant and had "a boy but it died". This is supported by Kate Dickens who said that Ellen had a son "who died in infancy". It is impossible to check this story as the birth records for the 1860s were destroyed during the Paris Commune in 1871.

Claire Tomalin has pointed out: "He (Dickens) was fifty, a grandfather, but pursuing a youthful love; a rich, eminent and powerful man in a position to bribe, fascinate and seduce an innocent girl. Whatever he offered her in the way of money and protection, she must lose her reputation in the process... If there was indeed a child... Nelly's disappearance from England would help to keep it secret... To give birth, to cherish for a few months perhaps, and then to lose a baby, is a terrible thing. It becomes more terrible if the child is not to be acknowledged and can be remembered only as a dreamlike guilty secret: first shame, then love, then grief."

In 1863 Dickens began to develop ideas for his next novel, Our Mutual Friend . He decided against running it in All the Year Around and on 8th September, Dickens agreed that he would produce Our Mutual Friend in twenty-monthly installments for Chapman and Hall. They agreed to pay £6,000 for 50% of the copyright. Dickens was to be paid in three installments: £2,500 on publication of the first number, and again at the sixth, then £1,000 when he delivered the final manuscript.

Dickens commissioned Marcus Stone to provide the illustrations. His previous novel, Great Expectations , did not have any illustrations so when Hablot Knight Browne heard the news he wrote to Robert Young about the decision: "Marcus is no doubt to do Dickens. I have been a good boy, I believe. The plates in hand are all in good time, so that I do not know what's up, any more than you. Dickens probably thinks a new hand would give his old puppets a fresh look, or perhaps he does not like my illustrating Trollope neck-and-neck with him - though, by Jingo, he need fear no rivalry there! Confound all authors and publishers, say I. There is no pleasing one or the other. I wish I had never had anything to do with the lot."

Dickens had used Browne as his illustrator for almost 30 years. It is believed that Dickens had felt that Browne had not given him the required support when he left his wife, Catherine Dickens. He was also probably upset by Browne's decision to provide illustrations for Once a Week , a periodical published by Bradbury and Evans. Dickens had fallen out with this company after its periodical, Punch Magazine , refused to publish his statement attacking Catherine in June 1858.

Peter Ackroyd has argued that Dickens had not been happy with Browne's illustrations for A Tale of Two Cities: "His work for Dickens had been falling off, and his illustrations for A Tale of Two Cities were woefully sketchy and undramatic. He had also been appearing in many different places, which cannot have helped him concentrate upon his Dickensian contributions. The really important fact remains, however, that the particular symbiotic relationship between writer and artist had now disappeared; Dickens no longer needed Browne to give visual strength to his imaginative conceptions, and Browne had ceased to develop and enlarge his range in response to Dickens's own progress as an artist. A separation was, in that sense at least, understandable.... Marcus Stone was younger and fresher than Hablot Browne, but by no means so good an artist... Dickens wanted a new look for his first serial novel in seven years... His work was much more contemporary and much more fashionable - more modern."

Dickens wrote the book in his Swiss chalet at Gad's Hill Place . He wrote to Charles Fechter: "I have never worked better anywhere." In March, 1864, Dickens had managed to complete the first three numbers and Chapman and Hall launched a massive advertising campaign. The first number of Our Mutual Friend was published on the last day of April. On 3rd May Dickens told John Forster : "Nothing can be better than Our Friend, now in his thirtieth thousand, and orders flowing in fast". It eventually sold 40,000 copies.

In the opening chapter, John Harmon, returns to London from South Africa to claim his inheritance from his recently deceased father. However, he can only inherit the money on the condition that he marries a woman he has not met, Miss Bella Wilfer. While in a waterside inn he is drugged, robbed, and thrown into the Thames, by George Radfoot. The cold water into which Harmon is plunged restores him to consciousness and, swimming to the shore, he escapes. Meanwhile, Radfoot is murdered by a fellow thief and is also thrown into the river. His body is discovered by Jesse Hexam and his daughter, Lizzie. As Radfoot was carrying the papers of his victim he is wrongly identified as Harman.

As the authorities believe that Harmon is dead the estate of £100,000 is inherited by Nicodemus Boffin, the servant of the elder Harmon. When he discovers the terms of the will, Harmon assumes the name of John Rokesmith, and obtains work as secretary to Boffin. He also arranges to meet Bella Wilfer. He falls in love with her but she does not return his affections. Bella is very close to her father. Claire Tomalin has argued: "They keep up their flirtation throughout the book, enacting the ageing man's dream of a young girl who devotes herself to making him happy. Bella is always hugging her father, arranging and rearranging his hair and smothering him with her hair. She ties his napkin on for him and pins him to the door, holding his ears while she kisses him all over his face... Contemporary critics, mostly middle-aged men, found Bella irresistibly charming. As you read the scenes between her and her father, it is tempting to see Dickens with Nelly, or with his daughter Katey, or with an amalgam of the two."

Boffin eventually discovers the true identity of Rokesmith and endeavours to win her love for him. This is successful and Rockesmith marries Bella. Boffin now discovers a second will hidden in a bottle. This revokes the earlier will and leaves everything to Boffin. However, he has grown found of Rockesmith and he transfers the entire property to the rightful heir, reserving for himself only the house occupied by his late master.

Peter Ackroyd, the author of Dickens (1990), has pointed out that Our Mutual Friend , like all his novels is full of contradictions. "In Our Mutual Friend, for example, the self-help of Betty Higden is lavishly praised while that of Bradley Headstone is scornfully condemned.... Sometimes Dickens will develop a character only to discard it; sometimes he will create an effective dramatic scene which only at the end of the book can be seen to have led nowhere at all. In the same way his language is filled with seems and perhaps and as if and a kind of and a sort of, as meanings and even values are improvised as he goes along with his story. Of course this is in part the result of serial publication, which meant that he never had the luxury of second or third drafts in order to resolve contradictions or clear up inconsistencies; but more importantly, it is also part of the man himself. Realism and fantasy. Comedy and pathos. Irony and sympathy."

Our Mutual Friend was not popular with the public and only 19,000 of the last number were sold. It was also disliked by the critics. Henry James gave the novel a terrible review in The Nation (21st December, 1865): "Our Mutual Friend is, to our perception, the poorest of Mr Dickens's works. And it is poor with the poverty not of momentary embarrassment, but of permanent exhaustion. It is wanting in inspiration. For the last ten years it has seemed to us that Mr Dickens has been. unmistakably forcing himself. Bleak House was forced; Little Dorrit was labored; the present work is dug out as with a spade and pickaxe." James then goes on to criticise Dickens's lack of insight into human nature: "Insight is, perhaps, too strong a word; for we are convinced that it is one of the chief conditions of his genius not to see beneath the surface of things. If we might hazard a definition of his literary character, we should, accordingly, call him the greatest of superficial novelists. We are aware that this definition confines him to an inferior rank in the department of letters which he adorns; but we accept this consequence of our proposition. It were, in our opinion, an offence against humanity to place Mr Dickens among the greatest novelists.... He has added nothing to our understanding of human character."

George Stott, condemned Dickens for being overly sentimental in The Contemporary Review: "Mr Dickens’s pathos we can only regard as a complete and absolute failure. It is unnatural and unlovely. He attempts to make a stilted phraseology, and weak and sickly sentimentality do duty for genuine emotion." However, he did go on to say that "we still hold him to be emphatically a man of genius."

Eneas Sweetland Dallas in The Times (29th November, 1865) was one critic who did like Our Mutual Friend : "We have read nothing of Mr Dickens's which has given us a higher idea of his power than this last tale... here he is in greater force than ever, astonishing us with a fertility in which we can trace no signs of repetition... It is infinitely better than Pickwick in all the higher qualities of a novel... He, who of all our living novelists has the most extraordinary genius, is also of all our living novelists the most careful and painstaking in his work. In all these 600 pages there is not a careless line." Dickens was so pleased with the review he sent Dallas the original manuscript. He wrote to George Childs that he would not write another novel for sometime. He received about £12,000 for the book but Chapman and Hall lost money on the venture. Dickens now found it much more profitable to give readings that writing novels.

Ellen Ternan next appears in the official record on 9th June 1865, when she was with her mother and on a train that crashed at Staplehurst. The accident was caused by men doing maintenance on the line who forget to inform the nearest station master. Ellen was in the front coach, which was the only one that did not leave the tracks. The rest of the coaches rolled down the bank and ten people were killed and 40 injured. Lucinda Hawksley takes up the story: "The accident was caused by a train worker loosening the plates that held the tracks together and then not tightening them again in time for the express train's arrival - he had misread the timetable and not realized the train was due to come through that afternoon. (Because the train connected with the boat from France, its timetable varied according to the tides.) The loosened rails were, catastrophically, on a bridge over the River Beult and several of the first-class carriages hurtled over the edge of the bridge - and dangled there. Charles Dickens and his two companions, Ellen Ternan and her mother, were in the first of the carriages not hanging down into the river. The back half of their carriage remained, precariously, on the bridge, but the front half stuck out into the abyss."

Dickens told an old friend Thomas Mitton what happened: "Two ladies were my fellow-passengers, an old one (Fanny Jarman Ternan) and a young one (Ellen Ternan). This is exactly what passed. You may judge it from the precise length of the suspense. Suddenly we were off the rail, and beating the ground as the car of a half-emptied balloon might. The old lady cried out and the young one screamed. I caught hold of them both." Dickens added that he told them: "Our danger must be over. Will you remain here without stirring, while I get out of the window?"

The following day Dickens wrote to the station master at Charing Cross: "A lady who was in the carriage with me in the terrible accident on Friday, lost, in the struggle of being got out of the carriage, a gold watch-chain with a smaller gold watch-chain attached, a bundle of charms, a gold watch-key, and a gold seal engraved Ellen. I promised the lady to make her loss known at headquarters, in case these trinkets should be found."

In 1865 Charles Fechter gave Dickens a chalet. His son, Henry Fielding Dickens has commented that: "It was so delightful to him that he used to love to work there in the summer time. It was indeed an ideal spot, where there was nothing to disturb him or arrest the play of his fancy or interfere with the working of his imagination." Dickens commented: "My room is up among the branches of the trees, and the birds and the butterflies fly in and out, and the green branches shoot in at the open windows; and the lights and shadows of the clouds come and go with the rest of the company. The scent of the flowers and, indeed, of everything that is growing for miles and miles is most delicious."

Dickens eventually forgave Charles Culliford Dickens for his support of his mother and marrying Bessie. In 1865 Charley, Bessie and their children spent Christmas at Gad's Hill Place. The following year Charley's paper business failed, leaving him bankrupt with personal debts of £1,000. Dickens now sacked Henry Morley, who had worked for him since 1851 and hired Charley as a sub-editor of All the Year Round.

Alfred D'Orsay Tennyson Dickens wanted to join the army but he failed his examinations in 1862. Unsuccessful attempts were made to enter the medical profession. In 1865 he decided to go to Australia to become a manager of a sheep station in New South Wales. The author, Arthur A. Adrian, has pointed out: "He sailed for Melbourne at the age of twenty, with introductions designed to facilitate contacts with some mercantile firm. Behind him he left a welter of unpaid bills. Wearily going through the itemized statements from the haberdasher and the tailor, his father found evidence of appalling extravagance - the curse that had already run through two generations of the family and now plagued the third. Eleven pairs of kid gloves (most of them the finest quality), eight silk scarves, three pairs of trousers, a treble milled coat and vest, as well as cambric handkerchiefs, cameo and onyx scarf pins, a railway rug, two umbrellas (one of brown silk), a silver mounted cane, a bottle of scent-all charged in a period of eleven months! And how were the eight pairs of ladies' gloves to be accounted for? Had any father ever been burdened with so many irresponsible sons?"

In 1866 Charles Dickens agreed to take part in a reading tour organised by Chappell Publishers. They employed George Dolby to manage the tour. Dolby later recalled: "Though I had known Mr. Dickens for some time previously, this was the first occasion on which I came into contact with him in a business matter; and there was naturally a feeling of constraint which might have made our first interview tedious but for that geniality, that antidote to reserve, which formed one of his chief characteristics." Dickens insisted that they should be accompanied by William Henry Wills, his assistant at All the Year Round. According to Dolby this was "not only for companionship, but to enable him the more easily to conduct the magazine during his absence from the metropolis." Dickens shook his hand and said: "I hope we shall like each other on the termination of the tour as much as we seem to do now."

The first tour lasted for three months and included London, Liverpool, Edinburgh, Manchester, Glasgow, Birmingham, Aberdeen and Portsmouth. Dolby later explained: "That Chappell had no reason to rue their bargain was shown by the fact that on the completion of the tour the gross receipts amounted to nearly £5,000. Such a success had never been known in any similar enterprise; and it was all the more gratifying as Mr. Dickens had, with that consideration for the masses which ever characterized his actions, stipulated, at the commencement of the engagement, that shilling seat-holders should have as good accommodation as those who were willing to pay higher sums for their evening's enjoyment." Dickens had insisted: "I have been the champion and friend of the working man all through my career, and it would be inconsistent, if not unjust, to put any difficulty in the way of his attending my readings."

In his book, Charles Dickens as I Knew Him, Dolby recorded that Dickens usually performed readings from Christmas Carol, Pickwick Papers and David Copperfield: "The scenes in which appeared Tiny Tim (a special favourite with him) affected him and his audience alike, and it not infrequently happened that he was interrupted by loud sobs from the female portion of his audience (and occasionally, too, from men) who, perhaps, had experienced the inexpressible grief of losing a child. So artistically was this reading arranged, and so rapid was the transition from grave to gay, that his hearers had scarcely time to dry their eyes after weeping before they were enjoying the fun of Scrooge's discovery of Christmas Day, and his conversation from his window with the boy in the court below. All these points told with wonderful effect, the irresistible manner of the reader enhancing a thousand times the subtle magic with which the carol is written."

By the end of the tour Dickens had became very close to Dolby. It has been argued that the two men "quickly developed an excellent rapport". Dickens told Dolby about his relationship with Ellen Ternan. It was Dolby's job to arrange meetings between Dickens and his mistress when he was touring. In one letter to his manager, Dickens commented: "In answer to your enquiry to Nelly - I do not think I shall be here until Wednesday in the ordinary course. But I can be in town on Tuesday at from 5 to 6, and will dine at the Posts with you, if you like."

In March 1867, James T. Fields agreed a deal with Charles Dickens to publish a fourteen volume edition of his works. Michael Slater, the author of Charles Dickens (2009) has commented: "On 16th April he (Dickens) wrote to Ticknor & Fields authorising them to state publicly that he had never profited from the reprinting of his works in America by any other publishers than themselves, except for Harper's payments to him for advance proof-sheets of the serial parts of his last three novels." Dickens letter also included the passage: "In America the occupation of my life for thirty years is, unless it bears your imprint, utterly worthless and profitless to me." As Slater has pointed out: "The publicising of this letter by Ticknor & Fields caused angry protests from other American publishers from whom Dickens had certainly received various payments. Ticknor and Fields defended themselves and Dickens as best they could and proceeded with their Diamond Edition in the anticipation that Dickens would soon commit himself to the readings tour in America that James Fields was eagerly trying to persuade him to undertake."

According to his friends, Dickens aged rapidly during his fifties. Blanchard Jerrold commented : "I met Dickens... at Charing Cross, and had remarked that he had aged very much in appearance. The thought-lines of his face had deepened, and the hair had whitened. Indeed, as he approached me, I thought for a moment I was mistaken, and that it could not be Dickens; for that was not the vigorous, rapid walk, with the stick lightly held in the alert hand, which had always belonged to him. It was he, however; but with a certain solemnity of expression in the face, and a deeper earnestness in the dark eyes." Edmund Yates recalled that he "looked jaded and worn, and had to a certain extent lost that marvellous elasticity of spirits which was his great characteristic."

Dickens wrote to his daughter, Maime Dickens on 7th April, 1867: "I cannot eat (to anything like the ordinary extent), and have established this system: At seven in the morning, in bed, a tumbler of new cream and two tablespoonful of rum. At twelve, a sherry cobbler and a biscuit. At three (dinner time), a pint of champagne. At five minutes to eight, an egg beaten up with a glass of sherry. Between the parts the strongest beef tea that can be made, drunk hot. At a quarter-past ten, soup, and anything to drink that I can fancy. I don't eat much more than half a pound of solid food in the whole four-and-twenty hours, if so much."

Dickens was also having problems with his left foot. He went to see the eminent surgeon, Henry Thompson, who said the problem was "friction of the shoe on a bunion-like enlargement" that had been complicated by erysipelas, a skin condition. In August 1867 Dickens wrote to Georgina Hogarth: "My foot is bad again, and I can't walk... I cannot get a boot on - wear a slipper on my left foot... I couldn't walk a quarter of a mile tonight for five hundred pounds". Percy Fitzgerald saw him in London and was shocked by his decline: "He was worn and drawn, and delved with wrinkles, and scored with anxiety, bronzed and burnished, and also wearing a very sad expression." During this period he also wore elastic stockings against the pain in his swollen foot and took laudanum to get a good night's sleep.

James T. Fields tried to encourage Dickens to carry out a reading tour of the United States. On 22nd May, 1866, he wrote to reject the suggestion: "Your letter is an excessively difficult one to answer, because I really do not know that any sum of money that could be laid down would induce me to cross the Atlantic to read. Nor do I think it likely that any one on your side of the great water can be prepared to understand the state of the case. For example, I am now just finishing a series of thirty readings. The crowds attending them have been so astounding, and the relish for them has so far outgone all previous experience, that if I were to set myself the task, 'I will make such or such a sum of money by devoting myself to readings for a certain time,' I should have to go no further than Bond Street or Regent Street, to have it secured to me in a day. Therefore, if a specific offer, and a very large one indeed, were made to me from America, I should naturally ask myself, 'Why go through this wear and tear, merely to pluck fruit that grows on every bough at home?' It is a delightful sensation to move a new people; but I have but to go to Paris, and I find the brightest people in the world quite ready for me. I say thus much in a sort of desperate endeavor to explain myself to you. I can put no price upon fifty readings in America, because I do not know that any possible price could pay me for them. And I really cannot say to any one disposed towards the enterprise, 'Tempt me,' because I have too strong a misgiving that he cannot in the nature of things do it."

Mary Dickens was one of those advising Dickens not to go on a reading tour of America. As she explained in Charles Dickens by His Eldest Daughter (1874): "For many years my father's public readings were an important part of his life, and into their performance and preparation he threw the best energy of his heart and soul, practising and rehearsing at all times and places. The meadow near our home was a favorite place, and people passing through the lane, not knowing who he was, or what doing, must have thought him a madman from his reciting and gesticulation. The great success of these readings led to many tempting offers from the United States, which, as time went on, and we realized how much the fatigue of the readings together with his other work were sapping his strength, we earnestly opposed his even considering."

In January 1867 Dickens began a four month tour that included Ireland and Wales. In Dublin it was feared that Dickens would encounter political protests. George Dolby explained: "As a precautionary measure, the public-houses were ordered to be closed from Saturday evening, March 16th (St. Patrick's Eve), till the following Tuesday morning. The public buildings had strong forces within their walls, and the troops were all confined to barracks. Notwithstanding all this, the city life went on as if no danger were anticipated, and hospitality played - as it always does in Dublin - a leading part in the affairs of life. At dinner, Mr. Dickens expressed a wish to make an inspection of the city, and as some of the guests at our friend's house had to do the same thing officially, his desire was very easily gratified. Returning to our hotel for a change of costume, we sallied forth in the dead of the night on outside cars, and under police care, to make a tour of the city; and so effectual were the precautions taken by the Government, that in a drive from midnight until about two o'clock in the morning, we did not see more than about half a dozen persons in the streets, with the exception of the ordinary policemen on their beats. Several arrests of suspected persons had been made in the night, and some of these became our fellow-travellers in the Irish mail on our return to England."

Dickens wrote to John Forster on 21st February, 1867: "The enthusiasm has been unbounded. On Friday night I quite astonished myself; but I was taken so faint afterwards that they laid me on a sofa, at the hall for half an hour. I attribute it to my distressing inability to sleep at night, and to nothing worse. Everything is made as easy to me as it possibly can be. Dolby would do anything to lighten the work, and does everything."

Charles Dickens eventually changed his mind about the American tour and on 13th June, 1867, he wrote to James T. Fields: "I have this morning resolved to send out to Boston in the first week in August, Mr. Dolby, the secretary and manager of my readings; He is profoundly versed in the business of these delightful intellectual feasts, and will come; straight to Ticknor and Fields, and will hold solemn council with them, and will then, go to New York, Philadelphia,. Hartford, Washington, etc, and see the rooms for himself and make his estimates.... We mean to keep all this strictly secret, as I beg of you to do, until I finally decide for or against. I am beleaguered by every kind of speculator, in such things on your side of the water; and it is very likely they would take the rooms over our heads - to charge us heavily for them - or would set on foot unheard - of devices for buying up the tickets, etc., if the probabilities oozed out."

After George Dolby returned to London an agreement was signed by Dickens with his American publishers, Ticknor and Fields. Dickens explained: "In making this calculation the expenses have been throughout taken on the New York scale, which is the dearest; as much as twenty per cent, has been deducted for management, including Mr. Dolby's commission; and no credit has been taken for any extra payment on reserved seats, though a good deal of money is confidently expected from this source. But, on the other hand, it is to be observed that four Readings (and a fraction over) are supposed to take place every week, and that the estimate of receipts is based on the assumption that the audiences are, on all occasions, as large as the rooms will reasonably hold. So considering eighty Readings, we bring out the net profit of that number remaining to me, after payment of all charges whatever, as £15,500."

On 9th November, 1867, Dickens left Liverpool on board the Cuba and following a rough passage, arrived in Boston ten days later. James T. Fields later recalled: "A few of his friends, under the guidance of the Collector of the port, steamed down in the custom-house boat to welcome him. It was pitch dark before we sighted the Cuba and ran alongside. The great steamer stopped for a few minutes to take us on board, and Dickens's cheery voice greeted me before I had time to distinguish him on the deck of the vessel. The news of the excitement the sale of the tickets to his readings had occasioned had been earned to him by the pilot, twenty miles out. He was in capital spirits over the cheerful account that all was going on so well, and I thought he never looked in better health. The voyage had been a good one, and the ten days' rest on shipboard had strengthened him amazingly he said. As we were told that a crowd had assembled in East Boston, we took him in our little tug and landed him safely at Long Wharf in Boston, where carriages were in waiting. Rooms had been taken for him at the Parker House, and in half an hour after he had reached the hotel he was sitting down to dinner with half a dozen friends, quite prepared, he said, to give the first reading in America that very night, if desirable. Assurances that the kindest feelings towards him existed everywhere put him in great spirits, and he seemed happy to be among us."

According to Fields, Charles Dickens insisted on going on a daily walk while in America. In an article published in The Atlantic Monthly he explained how important this daily exercise was to Dickens. "His favorite mode of exercise was walking; and... scarcely a day passed, no matter what the weather, that he did not accomplish his eight or ten miles. It was on these expeditions that he liked to recount to the companion of his rambles stories and incidents of his early life; and when he was in the mood, his fun and humor knew no bounds. He would then frequently discuss the numerous characters in his delightful books, and would act out, on the road, dramatic situations, where Nickleby or Copperfield or Swivelier would play distinguished parts. It is remembered that he said, on one of these occasions, that during the composition of his first stories he could never entirely dismiss the characters about whom he happened to be writing; that while the Old Curiosity Shop was in process of composition Little Nell followed him about everywhere; that while he was writing Oliver Twist Fagin the Jew would never let him rest, even in his most retired moments; that at midnight and in the morning, on the sea and on the land, Tiny Tim and Little Bob Cratchit were ever tugging at his coat-sleeve, as if impatient for him to get back to his desk and continue the story of their lives. But he said after he had published several books, and saw what serious demands his characters were accustomed to make for the constant attention of his already overtasked brain, he resolved that the phantom individuals should no longer intrude on his hours of recreation and rest, but that when he closed the door of his study he would shut them all in, and only meet them again when he came back to resume his task. That force of will with which he was so pre-eminently endowed enabled him to ignore these manifold existences till he chose to renew their acquaintance. He said, also, that when the children of his brain had once been launched, free and clear of him, into the world, they would sometimes turn up in the most unexpected manner to look their father in the face."

George Dolby reported that there was a great demand for tickets: "The scene in Boston was as nothing compared with the scene in New York, for the line of purchasers exceeded half a mile in length. The line commenced to form at ten o'clock on the night prior to the sale, and here were to be seen the usual mattresses and blankets in the cold streets, and the owners of them vainly endeavouring to get some sleep - an impossibility under the circumstances; for, leaving the bitter cold out of the question, the singing of songs, the dancing of breakdowns, with an occasional fight, made night hideous, not only to the peaceful watcher, but to the occupants of the houses in front of which the disorderly band had established itself. These ladies and gentlemen had my sincere sympathies; for my hotel was within fifty yards of the scene of action, and the shouting, shrieking, and singing of the crowd suggested the night before an execution at the Old Bailey, when executions were still public."

The first performance was at the Tremont Temple in Boston. According to Dolby: "The Tremont Temple had to be tested acoustically, a process that was always gone through in every new room in which he read. The process was very simple, and was conducted in the following manner. Mr. Dickens used to stand at his table, whilst I walked about from place to place in the hall or theatre, and a conversation in a low tone of voice was carried on between us during my perambulations. The hall having been pronounced perfect, a long walk was undertaken; and after a four o'clock dinner (as in England) and a sleep of an hour or so, we went to the Tremont Temple for the great event of the day."

Dolby pointed out in his book, Charles Dickens as I Knew Him (1885), that after he finished his reading from Christmas Carol "a dead silence seemed to prevail - a sort of public sigh as it were - only to be broken by cheers and calls, the most enthusiastic and uproarious, causing Mr. Dickens to break through his rule, and again presenting himself before his audience, to bow his acknowledgments." Dolby continued, "The reading being concluded, and the most enthusiastic signs of approval having been accorded to the reader in the form of recall after recall, Mr. Dickens indulged in his usual rub down, changing his dress-clothes for those he habitually wore when not en grande tenue, and a few of his most intimate friends were admitted into his dressing-room to offer their congratulations on the result of the evening's experiences."

On 21st November, 1867, James T. Fields and Annie Fields gave Dickens a dinner at their home, 37 Charles Street. His biographer, Peter Ackroyd, has commented: "James Fields, and his wife Annie Adams Fields... became his closest friends during the visit, Annie herself being then thirty-three while her husband was fifty." Dickens described Annie to Mamie Dickens as "a very nice woman, with a rare relish for humour and a most contagious laugh". Annie wrote in her diary that Dickens "bubbled over with fun" at the dinner and that he often "convulsed the company with laughter with... his queer turns of expression". She added that she was very lucky "to have known this great man so well." Dickens told Mamie that: "They are the most devoted friends, and never in the way, and never out of it." Michael Slater has argued: "Not only did the Fieldes provide him with a congenial domestic base (he actually stayed a few days in their house in early January, breaking his otherwise cast-iron rule about never accepting private hospitality during his reading tours), they also offered him an intimate and admiring friendship, firmly based upon their love for him as a great and good man and upon their unbounded admiration for his artistic genius."

Dickens was very open about his problems as a father and mother. Annie recorded, that he was "often troubled by the lack of energy his children show and has even allowed James to see how deep his unhappiness is in having so many children by a wife who is totally uncongenial." Although they did not meet Ellen Ternan he did tell James about her existence. This information was passed on to Annie. She wrote in her diary: "I feel the bond there is between us. She must feel it too. I wonder if we shall ever meet."

While in Boston he resumed his friendship with Ralph Waldo Emerson. Fields commented on Dickens's cheerfulness and high spirits. Emerson replied: "You see him quite wrong, evidently, and would persuade me that he is a genial creature, full of sweetness and amenities and superior to his talents, but I fear he is harnessed to them. He is too consummate an artist to have a thread of nature left. He daunts me! I have not the key."

Several people who saw Dickens commented on the way he was dressed. One journalist reported that at the reading he wore "light trousers with a broad stripe down the side, a brown coat bound with wide braid of a darker shade and faced with velvet, a flowering fancy vest... necktie secured with a jewelled ring and a loose kimono-like topcoat with wide sleeves and the lapels heavily embroidered, a silk hat, and very light yellow gloves."

Dickens spent the first six weeks of the tour reading in Boston and New York City. His manager, George Dolby, argues that Dickens "always regarded Boston as his American home, inasmuch as all his literary friends lived there". Weeks seven to eight was devoted to Philadelphia and Brooklyn. During weeks nine and eleven Dickens read in Baltimore and Washington. By this time Dickens was in poor health and his intended visits to Chicago and St Louis were cancelled. The reading tour was proving to be lucrative and on 15th January, 1868, Dolby paid in £10,000 to Dickens's bank.

Dickens took a brief rest before resuming his tour and in March visited Syracuse, Rochester, Buffalo, Albany, Portland and Maine. By this time he was suffering from the old problem of a swollen left foot. He told Mamie Dickens that he was mainly on a liquid diet. He listed his daily intake as being a tablespoonful of rum in a tumbler of fresh cream, a pint of champagne, an egg beaten up in sherry (twice) and soup, last thing at night.

On 22nd April, Dickens left for Liverpool on board the Russia . The New York Tribune reported: "It was a lovely day - a clear blue sky overhead - as he (Charles Dickens) stood resting on the rail, chatting with his friends, and writing an autograph for that one, the genial face all aglow with delight, it was seemingly hard to say the word 'Farewell,' yet the tug-boat screamed the note of warning, and those who must return to the city went down the side. All left save Mr. Fields. 'Boz' held the hand of the publisher within his own. There was an unmistakable look in both faces. The lame foot came down from the rail, and the friends were locked in each other's arms. Mr. Fields then hastened down the side, not daring to look behind. The lines were cast off. A cheer was given for Mr. Dolby, when Mr. Dickens patted him approvingly upon the shoulder, saying, 'Good boy'. Another cheer for Mr. Dickens, and the tug steamed away."

George Dolby reported after the tour: "The original scheme embraced eighty readings in all, of which seventy-six were actually given. Taking one city with another, the receipts averaged $3,000 each reading, but as small places such as Rochester, New Bedford, and many others of the same class did not exceed $2,000 a night, the receipts in New York and Boston (where the largest sum was taken), far exceeded the $3,000 mentioned above. The total receipts were $228,000, and the expenses were $39,000, including hotels, travelling expenses, rent of halls, etc., and, in addition, a commission of 5% to Messrs. Ticknor and Fields on the gross receipts in Boston. The advertising expenses were very trifling - a preliminary advertisement announcing the sale of tickets being all that was necessary. The hotels for Mr. Dickens, myself, and occasionally Mr. Osgood, and our staff of three men averaged $60 a day."

On his return Dickens decided to send the sixteen-year-old son, Edward, to Australia. He wrote to Alfred asking him to help his younger brother. He added that he could ride, do a little carpentering and make a horse shoe but raised doubts about whether he would take to life in the bush. Dickens gave Edward a letter the last time he saw him: "I need not tell you that I love you dearly, and am very, very sorry in my heart to part with you. But this life is half made up of partings, and these pains must be borne." He then urged him to leave behind the lack of "steady, constant purpose" and henceforth "persevere in a thorough determination to do whatever you have to do as well as you can do it". The letter concluded, "I hope you will always be able to say in after life, that you had a kind father".

Henry Fielding Dickens took Edward to Portsmouth. Henry later recalled: "He (Edward) went away, poor dear fellow, as well as could possibly be expected. He was pale, and had been crying, and had broken down in the railway carriage after leaving Higham station; but only for a short time." Dickens told a friend: "Poor Plorn has gone to Australia. It was a hard parting at the last. He seemed to become once more my youngest and favorite little child as the day drew near, and I did not think I could have been so shaken. These are hard, hard things, but they might have to be done without means or influence, and then they would be far harder. God bless him!"

Dickens was also having trouble with his son Sydney , who was an officer in the Royal Navy. Arthur A. Adrian has commented that " there were ominous signs that Sydney could not resist the family tendency toward extravagance". Sydney wrote to his father: "I must apply to you I am sorry to say and if you won't assist me I'm ruined". Dickens did pay off his debts but it was not long before he was asking for money again. "You can't understand how ashamed I am to appeal to you again... If any promises for future amends can be relied on you have mine most cordially, but for God's sake assist me now, it is a lesson I'm not likely to forget if you do and if you do not I can never forget. The result of your refusal is terrible to think of." Dickens wrote to his son, Henry, on 20th May, 1870: "I fear Sydney is much too far gone for recovery, and I begin to wish he were honestly dead." Dickens told his son that he was no longer welcome at Gad's Hill Place .

Claire Tomalin, the author of Dickens: A Life (2011) has pointed out that he was much more understanding of his eldest son, Charley's problems, than he was of those of his younger sons: "Sydney was cast off as Walter had been when he got into debt, and brother Fred when he became too troublesome, and Catherine when she opposed his will. Once Dickens had drawn a line he was pitiless. The conflicting elements in his character produced many puzzles and surprises. Why was Charley forgiven for failure and restored to favour, Walter and Sydney not? Because Charley was the child of his youth and first success, perhaps. But all his sons baffled him, and their incapacity frightened him: he saw them as a long line of versions of himself that had come out badly. He resented the fact that they had grown up in comfort and with no conception of the poverty he had worked his way out of, and so he cast them off; yet he was a man whose tenderness of heart showed itself time and time again in his dealings with the poor, the dispossessed, the needy, other people's children."

Dickens was influenced by the success of Wilkie Collins novels, The Woman in White (1859) No Name (1862), Armadale (1866) and The Moonstone (1868) , and he decided to write what became known as a sensation novel. According to one critic this was a story that "accentuated mystery and murder, crime and detection, madness and mayhem." The Mystery of Edwin Drood, would be his own attempt at this literary genre.

On 20th August, 1869, Dickens wrote to Frederic Chapman inviting him to make a proposal for publishing the new novel. He suggested that it should be published in twelve monthly parts rather than the traditional twenty. The following month he informed Chapman that he had chosen his son-in-law, Charles Allston Collins, to illustrate the book. Michael Slater, the author of Charles Dickens (2009), has pointed out: "Dickens... anxious, no doubt, to put his constantly ailing son-in-law in the way of earning some money... but wanted to see what he could do in the way of cover-design before he was formally commissioned."

Dickens's health continued to deteriorate. Dickens wrote to John Forster : "I am laid up with another attack in my foot, and was on the sofa all last night in tortures. I cannot bear to have the fomentations taken off for a moment. I was so ill with it on Sunday, and it looked so fierce, that I came up to Henry Thompson. He has gone into the case heartily, and says that there is no doubt the complaint originates in the section of the shoe, in walking, on an enlargement in the nature of a bunion." George Dolby commented that there was a "slow but steady change working in him".

On Christmas Day his foot was so swollen that he had to remain in his room. "He could not walk because of the pain and discomfort but, in the evening, he managed to hobble down to the drawing room in order to join his family in the usual festivities after dinner." Dickens lay on the sofa and watched the others playing games. He only joined in when the family played "The Memory Game". His son, Henry Fielding Dickens, later recalled in The Recollections of Sir Henry Dickens (1934): "My father, after many turns, had successfully gone through the long string of words and finished up with his own contribution, 'Warren's Blacking, 30 Strand'. He gave this with an odd twinkle in his eye and a strange inflection in his voice which at once forcibly arrested my attention and left a vivid impression on my mind for some time afterwards." This was of course a reference to the blacking warehouse, the site of his childhood labour and humiliation. However, it meant nothing to his family as none of them knew about this important part of his past.

Dickens signed the contract with Chapman and Hall to write The Mystery of Edwin Drood on 2nd February, 1870. The deal guaranteed him at least £650 per episode. Dickens also accepted a publisher's offer of £2,000 for early proof-sheets of the novel so that it could be published in the United States soon after it appeared in England. Dickens carried out research for the novel by visiting an opium den in Shadwell with his friend James Fields. Fields later recalled what happened: "During my stay in England in that summer of 1869, I made many excursions with Dickens both around the city and into the country.... Two of these expeditions were made on two consecutive nights, under the protection of police detailed for the service. On one of these nights we also visited the lock-up houses, watch-houses, and opium-eating establishments. It was in one of the horrid opium-dens that he gathered the incidents which he has related in the opening pages of Edwin Drood. In a miserable court we found the haggard old woman blowing at a kind of pipe made of an old penny ink-bottle. The identical words which Dickens puts into the mouth of this wretched creature in Edwin Drood we heard her croon as we leaned over the tattered bed on which she was lying."

In writing the story Dickens was also influenced by a serial by Robert Lytton, the son of Edward Bulwer-Lytton, that he had recently accepted for All the Year Round. The Disappearance of John Ackland had been written in such a way that the reader was kept wondering whether Ackland was murdered or had just gone missing. The mystery was only solved in the last installment of the story.

Charles Allston Collins designed a cover that Dickens was pleased with. However, soon afterwards he wrote to Frederic Chapman: "Charles Collins finds that the sitting down to draw, brings back all the worst symptoms of the old illness that occasioned him to leave his old pursuit of painting; and here we are suddenly without an illustrator! We will use his cover of course, but he gives in altogether as to further subjects."

Dickens asked his friend, John Everett Millais, to find a replacement for Collins. Soon afterwards he saw the drawing Houseless and Hungry in the first issue of The Graphic (4th December 1869). This was the work of the young artist, Luke Fildes. Millais burst into Dickens's room crying "I've got him". Dickens wrote to Fildes: "I see that you are an adept at drawing scamps, send me some specimens of pretty ladies." When he received these pictures he replied: "I can honestly assure you that I entertain the greatest admiration for your remarkable powers." Fildes wrote to his artist friend, Henry Woods: "Congratulate me! I am to do Dickens's story. Just got the letter settling the matter. Going to see Dickens on Saturday... My heart fails me a little for it is the turning point in my career. I shall be judged by this."

The first installment of The Mystery of Edwin Drood was published on 31st March 1870. Dickens was delighted when he heard that 50,000 were sold over the next few days. He wrote to James Fields on 18th April: "It has very, very far outstripped every one of its predecessors." It also enjoyed good reviews from the press. The Times commented: "As he delighted the fathers, so he delights the children, and this his latest effort promises to be received with interest and pleasure as widespread as that which greeted those glorious Pickwick Papers which built at once the whole edifice of his fame."

The Dublin Review suggested: "The plot of The Mystery of Edwin Drood echoes that of Our Mutual Friend quite closely: two young people are betrothed and doubtful of the arrangement; the young man disappears and the young woman, believing him dead, is closely guarded by an eccentric friend of the vanished gentleman." Wilkie Collins was not impressed with the novel and commented that it was Dickens's "last laboured effort, the melancholy work of a worn-out brain".

The Mystery of Edwin Drood opens with John Jasper, the choirmaster at Cloisterham Cathedral, in an opium den. The next evening, Jasper's nephew, Edwin Drood visits him. Drood tells him that he has misgivings about his betrothal to Rosa Bud, who is one of Jasper's students. It had been his father's dying wish that he should marry Rosa. Soon afterwards Drood meets Neville Landless and his sister Helena, who are pursuing their studies under the direction of the Reverend Septimus Crisparkle. Neville takes a dislike to Edwin over the way he treats Rosa.

One night, Neville and Edwin visit John Jasper's lodgings to have a glass of wine. The two men leave together and become involved in a fight. Jasper separates them and reports Neville's behaviour to Crisparkle. Edwin decides to break-off his engagement to Rosa. The following day Edwin disappears. Jasper is concerned about the safety of his nephew and suggests that Neville might be responsible for his disappearance. Neville is arrested but without any hard evidence against him, he is eventually released.

According to Arthur Allen Adrian, the author of Georgina Hogarth and the Dickens's Circle (1957) Georgina Hogarth asked Dickens about the progress of the novel: "The novel was giving him some difficulty; he felt that he had revealed too much of the plot in the early part. Yielding to her curiosity, she inquired boldly, 'I hope you haven't really killed poor Edwin Drood'. He replied gravely, 'I call my book the Mystery, not the History, of Edwin Drood'. From this answer she could not determine whether he meant the story to remain a mystery for ever, or only until the proper time for revealing its secret."

Dickens' health deteriorated during the writing of The Mystery of Edwin Drood. He told his daughter Kate Dickens Pergugini that he was pleased by the reception the first three episodes had received and that he hoped "I live to finish it". Seeing Kate's startled look, he explained, "I say if, because you know, my dear child, I have not been strong lately."

Dolby continued to see Dickens on a regular basis after he returned to London. He recorded in his book, Charles Dickens as I Knew Him (1885): "The last time I saw Charles Dickens, was on Thursday, June 2, 1870, when I made one of my weekly visits to the office. Getting there just in time for luncheon, I found him greatly absorbed in business matters, and although the same old greeting was awaiting me, it was painfully evident that he was suffering greatly both in mind and body. During luncheon, many plans for the future were talked of between us, amongst others an early visit to Gad's Hill, where we were to make a thorough inspection of the new conservatory, and several other improvements, in which both of us were greatly interested. But he was very busy that afternoon, and I rose to leave earlier than usual. Then came our final parting, though we neither of us thought of it as such. We shook hands across the office-table, and after a hearty grasp of the hand, and the words from him, 'next week then,' I turned to go, though with a troubled sense that I was leaving my chief in great pain. He rose from the table, and followed me to the door; I noticed the difficulty of his walk, and the pained look on his face, but was unwilling to speak, so without another word on either side, we parted."

Charles Dickens died on 8th June, 1870. The traditional version of his death was given by his official biographer, John Forster. He claimed that Dickens was having dinner with Georgina Hogarth at Gad's Hill Place when he fell to the floor: "Her effort then was to get him on the sofa, but after a slight struggle he sank heavily on his left side... It was now a little over ten minutes past six o'clock. His two daughters came that night with Mr. Frank Beard, who had also been telegraphed for, and whom they met at the station. His eldest son arrived early next morning, and was joined in the evening (too late) by his youngest son from Cambridge. All possible medical aid had been summoned. The surgeon of the neighbourhood (Stephen Steele) was there from the first, and a physician from London (Russell Reynolds) was in attendance as well as Mr. Beard. But human help was unavailing. There was effusion on the brain."

The Times reported on 11th June, 1870: "During the whole of Wednesday Mr Dickens had manifested signs of illness, saying that he felt dull, and that the work on which he was engaged was burdensome to him. He came to the dinner-table at six o'clock and his sister-in-law, Miss Hogarth, observed that his eyes were full of tears. She did not like to mention this to him, but watched him anxiously, until, alarmed by the expression of his face, she proposed sending for medical assistance.... Miss Hogarth went to him, and took his arm, intending to lead him from the room. After one or two steps he suddenly fell heavily on his left side, and remained unconscious and speechless until his death, which came at ten minutes past six on Thursday, just twenty-four hours after the attack."

George Dolby went to Gad's Hill Place as soon as he heard the news: "I went to Gad's Hill at once, where I was most kindly and gently received by Miss Dickens and Miss Hogarth, who told me the story of his last moments. The body lay in the dining-room, where Mr. Dickens had been seized with the fatal apoplectic fit. They asked me if I would go and see it, but I could not bear to do so. I wanted to think of him as I had seen him last. I went away from the house, and out on to the Rochester road. It was a bright morning in June, one of the days he had loved; on such a day we had trodden that road together many and many a time. But never again, we two, along that white and dusty way, with the flowering hedges over against us, and the sweet bare sky and the sun above us. We had taken our last walk together."

After the publication of her book, The Invisible Woman (1990), Claire Tomalin received a letter from J. C. Leeson, telling her a story that had been passed down in the family, originating with his highly respectable great-grandfather, a Nonconformist minister, J. Chetwode Postans, who became pastor of Lindon Grove Congregational Church in 1872. He was told later by the caretaker that Charles Dickens did not collapse atGad's Hill Place, but at another house "in compromising circumstances". Tomalin took a keen interest in this story as at the time, Ellen Ternan was living at nearby Windsor Lodge. After investigating all the evidence Tomalin has speculated that Dickens was taken ill while visiting the home he rented for Ternan. She then arranged for a horse-drawn vehicle to take Dickens to Gad's Hill.

John Everett Millais was invited to draw Dickens's dead face. On 16th June, Kate Dickens Perugini wrote to Millais: "Charlie - has just brought down your drawing. It is quite impossible to describe the effect it has had upon us. No one but yourself, I think, could have so perfectly understood the beauty and pathos of his dear face as it lay on that little bed in the dining-room, and no one but a man with genius bright as his own could have so reproduced that face as to make us feel now, when we look at it, that he is still with us in the house. Thank you, dear Mr. Millais, for giving it to me. There is nothing in the world I have, or can ever have, that I shall value half as much. I think you know this, although I can find so few words to tell you how grateful I am."

The Times ran an editorial calling for Dickens to be buried in Westminster Abbey. This was readily accepted and on 14th June, 1870, his oak coffin was carried in a special train from Higham to Charing Cross Station. The family travelled on the same train and they were met by a plain hearse and three coaches. Only four of his children, Charles Culliford Dickens, Mamie Dickens, Kate Dickens Collins and Henry Fielding Dickens attended the funeral. George Augustus Sala gave the number of mourners as fourteen.

Dickens's last will and testament, dated 12th May 1869 was published on 22nd July. As Michael Slater has commented: "Like Dickens's novels, his last will has an attention-grabbing opening" as it referred to his mistress, Ellen Ternan. It stated: "I give the sum of £1,000 free of legacy duty to Miss Ellen Lawless Ternan, late of Houghton Place, Ampthill Square, in the county of Middlesex." It is assumed that he made other, more secret, financial arrangements for his mistress. For example, it is known that she received £60 a year from the house he owned in Houghton Place. According to her biographer, she was now a "woman approaching middle age, in delicate health, solitary and inured to dependence on a man who could give her neither an honourable position nor even steady companionship."

The total estate amounted to over £90,000. "I give the sum of £1,000 free of legacy duty to my daughter Mary Dickens. I also give to my said daughter an annuity of £300 a year, during her life, if she shall so long continue unmarried; such annuity to be considered as accruing from day to day, but to be payable half yearly, the first of such half yearly payments to be made at the expiration of six months next after my decease. If my said daughter Mary shall marry, such annuity shall cease; and in that case, but in that case only, my said daughter shall share with my other children in the provision hereinafter made for them."

Dickens used the will to highlight the role that Georgina Hogarth had played in his life: "I give to my dear sister-in-law Georgina Hogarth the sum of £8,000 free of legacy duty. I also give to the said Georgina Hogarth all my personal jewellery not hereinafter mentioned, and all the little familiar objects from my writing-table and my room, and she will know what to do with those things. I also give to the said Georgina Hogarth all my private papers whatsoever and wheresoever, and I leave her my grateful blessing as the best and truest friend man ever had."

Primary Sources

(1) Henry James, The Nation (21st December 1865)