Charles Allston Collins

Charles Allston Collins, the youngest of the two children of the painter William John Thomas Collins (1788–1847), and his wife, Harriet Geddes Collins (1790–1868), was born on 25th January 1828 at Pond Street, Hampstead. His brother, Wilkie Collins, was born in 1824.

At the age of nineteen Collins entered the Royal Academy Schools where he formed lasting friendships with William Holman Hunt and John Everett Millais, and became associated with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. The critic, John Ruskin, praised Collins's work for "its meticulous attention to botanical detail."

As a young man he had an accident in which he nearly drowned. As a result Collins was petrified by water. Millais later wrote, "One could not induce him to commit his body (for fear of drowning) within a coffin bath of hot water". He remained an extremely nervous man throughout his life. He told Holman Hunt that whenever he tried to paint, he had acute stomach pains and admitted "the extreme suffering and anxiety which painting causes me". Wilkie Collins later explained: "It was in the modest and sensitive nature of the man to underrate his own success. His ideal was a high one; and he never succeeded in satisfying his own aspirations".

Important paintings by Collins included Berengaria's Alarm (1850), Convent Thoughts (1851), May in the Regent's Park (1852), and Good Harvest of 1854 (1855). He also painted the portrait of Georgina Hogarth as Lady Grace (1855). It has been claimed by John Everett Millais that he often left his paintings half-finished. William Holman Hunt noted that "Collins... could have held the field for us had he done himself justice in design and possessed courage to keep his purpose… he continually lost heart when any painting had progressed half-way toward completion, abandoning it for a new subject, and this vacillation he indulged until he had a dozen or more unfinished canvases never to be completed."

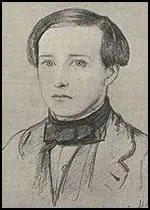

William Holman Hunt described Collins as "slight, with slender limbs, but erect in the head and shoulders, beautifully cut features, large chin, a crop of orange-coloured hair (latterly a beard), blue eyes that looked at a challenger without a sign of quailing."

Wilkie Collins introduced Charles Allston Collins to Charles Dickens, who gave him work providing articles in Household Words . Collins first book, The New Sentimental Journey, sketches of his Parisian visits, was serialized between 11th June and 9th July 1859, in Dickens's journal, All the Year Round . Collins also published The Eye-Witness: And His Evidence about Many Wonderful Things (1860).

Collins wanted to marry Dickens's daughter, Kate Macready Dickens. At first Dickens refused permission because he disapproved of Wilkie living with Caroline Graves, a shop girl who had an illegitimate child. Kate was also unsure but as she later recalled, that he had left her mother, Catherine Dickens, after beginning a relationship with Nellie Ternan: "My father was like a madman... This affair brought out all that was worst - all that was weakest in him. He did not care a damn what happened to any of us. Nothing could surpass the misery and unhappiness of our home."

Eventually Charles Dickens agreed to Kate's marriage to Collins. He wrote to his friend, W.W. F. de Cerjat, about his thoughts on the matter: "My second daughter (Kate) is going to be married in the course of the summer, to the brother of Wilkie Collins the novelist. He was bred an artist (the father was one of the most famous painters of English green lanes and coast pieces), and was attaining considerable distinction, when he turned indifferent to it and fell back upon that worst of cushions, a small independence. He is a writer too, and does the Eye Witness in All The Year Round. He is a gentleman, and accomplished.... I do not doubt that the young lady might have done much better, but there is no question that she is very fond of him, and that they have come together by strong attraction. Therefore the undersigned venerable parent says no more, and takes the goods the Gods provide him."

Collins married Kate on 17th July 1860, at Gad's Hill Place. Dickens's biographer, Claire Tomalin , has pointed out: "Kate married Wilkie's brother, Charles Collins, thirty-two to her twenty, a good-natured man but a semi-invalid, who was giving up art to try to write. Dickens blamed himself for Kate's decision, knowing she was marrying without love and to get away from home, but he put on a showy wedding at Gad's with a semi-invalid, who was giving up art to try to write." That evening Mamie Dickens found her father weeping into her sister's wedding dress, and he told her how much he blamed himself for the marriage.

The couple moved to Paris. In December 1860, Kate told her mother-in-law about the early months of their marriage: "To begin at the beginning then, we are economizing. We keep no servant and we do almost everything for ourselves, not everything though, we pay the cook of the house something to wash up the dishes for us, and the servant of the house makes the beds and does the rooms for us, that is to say pretends to do the rooms, really we do them. Without this help of course we should be obliged to keep a servant of our own, as we shall do if we stay here, when we have a little recovered from the expense of our journey. We have cleaned everything with our own hands and have scrubbed away like two hard working servants. We cook our own food, no one in the world could cook a chop better than Charlie does, and I am very great indeed at boiled rice. In the morning Charlie lights the fire and I lay the cloth, while he fries the bacon I make the tea. After breakfast I clear away, put his writing materials out on the table and he sets down to work while I wash up the breakfast cups in the kitchen, put away everything, sweep up the crumbs and the hearth and get the room neat. Then Charlie goes on working all the morning till about two, and I darn, or mend, or write letters. At two we have our lunch, then a little more work & then we go out for a walk, get what things we want for dinner, come in, cook our dinner and eat it."

The marriage was not a success. Gordon H. Fleming, the author of John Everett Millais (1998) claims that "Charles Collins was incurably impotent". This story is backed-up by Peter Ackroyd, in his book, Dickens (1990): "Dickens was very much opposed to the match, not least because he was unsure of Collins himself... It has been suggested that he was homosexual. Kate herself seems to have told her father that her husband was impotent. Certainly they had no children, and in addition he suffered from a mysterious, wasting illness throughout most of their married life."

Collins wrote three novels: The Bar Sinister: A Tale (1864), Strathcairn (1864) and At the Bar: A Tale (1866). Collins remained a valued friend of William Holman Hunt: "He was in many respects a good rein to me, being timid and therefore sure to put on the curb, and who was one of the men I valued in life as thoroughly fearing and loving God through all of his rather eccentric changes in faith. He might now be a better advisor but must not be so. In this world it is evident that the Father would rather we stumbled than walked with leading strings forever."

Charles Allston Collins became extremely ill. Wilkie Collins has pointed out: "The last years of Charles's life were years of broken health and acute suffering, borne with a patience and courage known only to those nearest and dearest to him." It is now believed that Collins was suffering from stomach cancer.

On 20th August, 1869, Charles Dickens wrote to Frederic Chapman inviting him to make a proposal for publishing the new novel, The Mystery of Edwin Drood. He suggested that it should be published in twelve monthly parts rather than the traditional twenty. The following month he informed Chapman that he had chosen his son-in-law, Collins, to illustrate the book. Michael Slater, the author of Charles Dickens (2009), has pointed out: "Dickens... anxious, no doubt, to put his constantly ailing son-in-law in the way of earning some money... but wanted to see what he could do in the way of cover-design before he was formally commissioned."

Collins designed a cover that Dickens was pleased with. However, soon afterwards he wrote to Frederic Chapman: "Charles Collins finds that the sitting down to draw, brings back all the worst symptoms of the old illness that occasioned him to leave his old pursuit of painting; and here we are suddenly without an illustrator! We will use his cover of course, but he gives in altogether as to further subjects." John Everett Millais suggested to Dickens that he should ask the young artist Luke Fildes to complete the job.

On 7th July, 1867, Dickens told his friend, James T. Fields: "Charley Collins is - I say emphatically - dying. Only last night I thought it was all over. He is reduced to that state of weakness, and is so racked and worn by a horrible strange vomiting, that if he were to faint - as he must at last - I do not think he could be revived."

Charles Allston Collins died on 9th April 1873 at 10 Thurloe Place, South Kensington, aged forty-five, from a cancerous tumour in the stomach.

Primary Sources

(1) Charles Dickens, letter to W.W. F. de Cerjat (May, 1860)

My second daughter (Kate) is going to be married in the course of the summer, to the brother of Wilkie Collins the novelist. He was bred an artist (the father was one of the most famous painters of English green lanes and coast pieces), and was attaining considerable distinction, when he turned indifferent to it and fell back upon that worst of cushions, a small independence. He is a writer too, and does the Eye Witness in All The Year Round. He is a gentleman, and accomplished.... I do not doubt that the young lady might have done much better, but there is no question that she is very fond of him, and that they have come together by strong attraction. Therefore the undersigned venerable parent says no more, and takes the goods the Gods provide him.

(2) Charles Dickens, letter to James T. Fields (7th July, 1867)

Charley Collins is - I say emphatically - dying. Only last night I thought it was all over. He is reduced to that state of weakness, and is so racked and worn by a horrible strange vomiting, that if he were to faint - as he must at last - I do not think he could be revived. My man came into my room yesterday morning to say 'Mr. Collins, Sir, he is that bad, and he looks that awful, and Mrs. Collins called me to him just now, that brought down by his dreadful sickness. As it has turned me over Sir.' And last night we all felt (except Katie before whom we say nothing) that he might be dead in half an hour.