Oliver Lawn

Oliver Lawn was born in 1919. He was educated at Jesus College. He was a talented mathematician and in 1940 he was asked to visit one of the tutors, Gordon Welchman: "At the time, I was doing maths tripos at Cambridge. When I finished my tripos, my Part Three, in 1940, I expected to be called straight up into the army - Engineers or whatever. When I went up to Cambridge in July to take my degree, I was asked to go and see a chap called Gordon Welchman, who I knew by name, but not in person. He was a mathematics lecturer, who had not been one of my lecturers." (1)

Welchman recruited Lawn to work at the the Government Code and Cypher School moved to Bletchley Park. Bletchley was selected simply as being more or less equidistant from Oxford University and Cambridge University since the Foreign Office believed that university staff made the best cryptographers. The house itself was a large Victorian Tudor-Gothic mansion, whose ample grounds sloped down to the railway station. Lodgings had to be found for the cryptographers in the town. (2)

Government Code and Cypher School

Oliver Lawn arrived with Keith Batey, another graduate from Cambridge. Batey later recalled how they were trained by Hugh Alexander: "I arrived with two other chaps from the maths tripos. We were greeted at the Registry and were immediately given a quick lecture on the German wireless network. And I did not pay much attention because I was focusing on these highly nubile young ladies who were wandering about the Park. Anyway, after twenty minutes of this lecture, which told us absolutely nothing, we were handed over to Hugh Alexander, who was the chess champion. He sat us down in front of what later turned out to be a steckered Enigma, and he talked about it. It didn't have a battery, it didn't work. And then we were just told to get on with it. That was the cryptographic training." (3)

Oliver Lawn joined a team with Gordon Welchman in Hut 6 at Bletchley Park, which was concerned with breaking the Enigma Codes used by the German Army and Air Force. (4) Despite the poor training he soon became a talented codebreaker: "These were basically mathematical problems and I had been trained as a mathematician, to spend my life doing these problems. This was just another form of problem." The translated messages were then passed on to the "intelligence people" and they "could decide what information, if any, to pass on to whom... they were supported by a huge card index." (5)

Enigma Machine

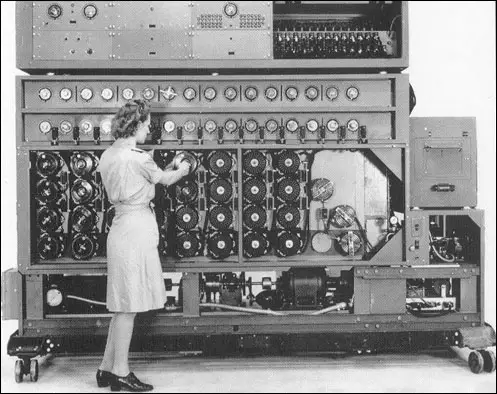

Alan Turing set about developing an engine that would increase the speed of the checking process. Turing finalized the design at the beginning of 1940, and the job of construction was given to the British Tabulating Machinery factory at Letchworth. The engine (called the "Bombe") was in a copper-coloured cabinet. (6) "The result was a huge machine six-and-a-half feet tall, seven feet long and two feet wide. It weighed over a ton, with thirty-six 'scramblers' each emulating an Enigma machine and 108 drums selecting the possible key settings." (7) Its chief engineer, Harold Keen, and a team of twelve men, built it in complete secrecy. Keen later recalled: "There was no other machine like it. It was unique, built especially for this purpose. Neither was it a complex tabulating machine, which was sometimes used in crypt-analysis. What it did was to match the electrical circuits of Enigma. Its secret was in the internal wiring of (Enigma's) rotors, which 'The Bomb' sought to imitate." (8)

To be of practical use, the machine would have to work through an average of half a million rotor positions in hours rather than days, which meant that the logical process would have to be applied to at least twenty positions every second. (9) The first machine, named Victory, was installed at Bletchley Park on 18th March 1940. It was some 300,000 times faster than Rejewski's machine. (10) "Its initial performance was uncertain, and its sound was strange; it made a noise like a battery of knitting needles as it worked to produce the German keys." (11) They were described by operators as being "like great big metal bookcases". (12)

Frederick Winterbotham was the chief of Air Intelligence at MI6. He later described the moment when Major General Sir Stewart Menzies, the chief of MI6, first gave him copies of German secret messages: "It was just as the bitter cold days of that frozen winter were giving way to the first days of April sunshine that the oracle of Bletchley spoke and Menzies handled me four little slips of paper, each with a short Luftwaffe message on them... From the Intelligence point of view they were of little value, except as a small bit of administrative inventory, but to the back-room boys at Bletchley Park and to Menzies... they were like the magic in the pot of gold at the end of the rainbow. The miracle had arrived." (13)

A more improved version, called Agnus Dei (Lamb of God), was delivered on 8th August. From this point onwards, Bletchley Park was able to read, on a daily basis, every single Luftwaffe message - something in the region of one thousand a day. (14) At the time, the Battle of Britain was raging and the German codes were being broken at Bletchley Park, allowing the British to direct their fighters against incoming German bombers. When the battle was won the codebreakers intercepted messages cancelling the planned invasion of Britain - Operation Sealion. (15)

Oliver Lawn pointed out: "After the first two, a large number of machines were made to a fairly standard form. It proved its use. Altogether about two hundred were made. The first ones were located at Bletchley itself, in what is now called the Bombe Room, which still exists. But when the numbers grew bigger, they had to use other places, and as the war went on, most of them were put at two locations in north London - Eastcote and Stanmore. They had roughly a hundred machines each, run by a large company of Wrens in both cases." (16)

Lawn later explained how it worked: "I was concerned with the codebreaking and that was it. When the code had been broken, the decoded message was passed through to the Intelligence people who used the information - or decided whether to use it. The content of messages was of no concern to me at all. I knew enough German to get an idea of what it was all about. But I had no idea of the context. And it wasn't my business. I could read the messages but they were so much in telegraphese, jargon, that they would mean nothing." (17)

Oliver Lawn & Shelia MacKenzie

There was a lot of romance at Bletchley Park. Keith Batey became involved with Mavis Lever. He felt guilty about working at the Government Code and Cypher School while so many of his contemporaries were risking their lives in open combat. "Accordingly he told his bosses that he wanted to train as a pilot, only to be informed that no one who knew that the British were breaking Enigma could be allowed to fly in the RAF, the risk being that he might be shot down and captured. Batey then suggested that he join the Fleet Air Arm, flying over the sea in defence of British ships, arguing that he would be either killed or picked up by his own side. Worn down by his persistence, his superiors reluctantly agreed." Keith married Mavis in November, 1942, shortly before he left for Canada for the Fleet Air Arm advanced flying course. (18)

Oliver Lawn had fallen in love with Shelia MacKenzie, another codebreaker at GCCS. Oliver later recalled that several other codebreakers married while working at Bletchley Park, including Robert Roseveare and Dennis Babbage: "There was quite a bit of romance. There were several in Hut 6 who married while they were at Bletchley. There were the Bateys, of course... The other couple I recollect was Bob Roseveare and Ione Jay. He was a mathematician, straight from school. He hadn't even gone to university. Very brilliant chap from Marlborough. He married Ione Jay, who was one of the girls in Hut 6. Then there was Dennis Babbage, who was a don similar to Gordon Welchman. Same sort of age. Babbage married while he was there." (19)

According to Sandra Laville, Oliver Lawn, "deciphered more than 5,000 German codes during the war, using the enigma machine. He and his colleagues helped to divert German bombers from British cities by breaking the codes that set the radio beams the Nazis used to lead their planes to the target. The successes of the decipherers is thought to have shortened the war by two years." (20)

Oliver Lawn - Post 1945

At the end of the Second World War Oliver Lawn began teaching at Reading University: "By that time, I had more or less forgotten all my mathematics, in five years of doing codebreaking. Then I took the Civil Service exams in the spring of 1946. I could have gone scientific or administrative civil service. I was successful in both but I decided, on the whole, to go for the administration, rather than the specialist science as a mathematician. I joined the civil service around July 1946." (21)

Shelia Lawn returned to Aberdeen University to finish her degree. She followed by a Social Science Diploma at Birmingham University. Shelia and Oliver married in May 1948. (22) "When Oliver and I married, we could only get dockets for basic furniture. But Oliver had a great-aunt who died and some of her beautiful furniture came to us... There was very little fuel and very little hot water. That was even worse than during the war. Everything was rationed, including potatoes and bread. And clothes were rationed until 1952." (23)

They moved to London and Shelia Lawn found work in the Personnel Department with London Transport. Oliver worked in several Government Departments, including the Department of the Environment. Shelia later had two children, David and Richard. (24)

Shelia Lawn had signed the Official Secrets Act and never told her father about her work at the the Government Code and Cypher School. "What I regretted was that my father died long before I could reveal anything. He died in 1961... I am so sorry my father couldn't have... he would have been so interested." Oliver Lawn commented: "My parents were the same. They both died in the 1960s... Most people were in the same situation. Relatives who should have known, but who couldn't be told. And then died." (25)

On retirement in 1978 they moved to Sheffield, and have been involved there with a number of voluntary and charitable activities.

Primary Sources

(1) Oliver Lawn, interviewed by Sinclair McKay, for the book, The Secret Life of Bletchley Park (2010)

After the first two, a large number of machines were made to a fairly standard form. It proved its use. Altogether about two hundred were made. The first ones were located at Bletchley itself, in what is now called the Bombe Room, which still exists. But when the numbers grew bigger, they had to use other places, and as the war went on, most of them were put at two locations in north London - Eastcote and Stanmore. They had roughly a hundred machines each, run by a large company of Wrens in both cases....

I was concerned with the codebreaking and that was it. When the code had been broken, the decoded message was passed through to the Intelligence people who used the information - or decided whether to use it. The content of messages was of no concern to me at all. I knew enough German to get an idea of what it was all about. But I had no idea of the context. And it wasn't my business. I could read the messages but they were so much in telegraphese, jargon, that they would mean nothing.

(2) Roger Marsh, Shelia and Oliver Lawn (31st August 2005)

Oliver and Sheila Lawn both worked at Bletchley Park in Buckinghamshire, the very secret wartime code breaking establishment. It was called the Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ). All the work done at Bletchley Park remained Top Secret for some 30 years after the war, and only then were Oliver and Sheila able to talk about their work there.

Oliver Lawn was recruited for Bletchley Park by Gordon Welchman in July 1940. He had just completed a Mathematics Degree at Jesus College, Cambridge, and had expected then to be called up into the Army, as many of his contemporaries were being. Gordon Welchman, a Cambridge Mathematics Don, had been recruited for Bletchley at the beginning of the War in September 1939, along with other Oxford and Cambridge Dons, who included Alan Turing. In July 1940 Welchman was recruiting other Mathematicians, and Oliver was one of these.

He joined a team with Welchman in Hut 6 at Bletchley Park, which was concerned with breaking the Enigma Codes used by the German Army and Air Force. (The Enigma Codes used by the German Navy were different, and were broken by a quite different group of people, in Hut 5.) He remained in Hut 6 for 5 years, until September 1945.

The methods mostly used for breaking these Enigma Codes were by guessing "cribs" - that is, guessing what some part of an encoded message actually said, in German. This was of course only possible for "routine" messages such as daily weather reports or forecasts, which often began, or ended with a standard phrase, or a record of the time of sending (e.g. "Wettervorhersage" or "nullsechsnullnull" "0600" hours). By aligning such phrases with the encoded text which was received over the radio in Morse code, pairs of text letters and encoded letters were thrown up, and these were grouped into "menus" looking rather like diagrams of Euclidean Geometry. The menus were then tested by large machines called "Bombes", seeking the correct setting of the Enigma machine at which the message had been encoded - the daily "key". When this "key" had been found, all the messages on that key, and on that day, could be decoded. Keys changed daily at midnight, and each day's key had to be separately discovered. There were separate daily keys for different parts of the German Services. The total number of possible Keys was 150 million million million.

(3) Sandra Laville, The Guardian (12th May 2004)

For 250 years it has exercised the minds of theologians, historians and scientists. Charles Darwin was observed pondering its meaning, and Josiah Wedgwood spent many an hour attempting to decipher its cryptic inscription. Some hope it may hold the secret of the whereabouts of the Holy Grail.

Books have been written, documentary films made and poems penned in an attempt to explain it, but the mystery contained in an 18th century monument in the grounds of Lord Lichfield's estate in Staffordshire has eluded interpretation.

In the hope of succeeding where so many others have failed and finally cracking the conundrum, a group of veteran codebreakers from Bletchley Park arrived at Shugborough House near Milford yesterday, armed with proven grey matter and years of experience in deciphering the German enigma codes.

Tucked away within the 900-acre grounds, they found their puzzle: a stone monument built around 1748, containing a carved relief of Nicholas Poussin's Les Bergers d'Arcadie II in reverse. The picture shows a female figure watching as three shepherds gather around a tomb and point at letters within an inscription carved upon it, which read: Et in Arcadia Ego! (And I am in Arcadia too.) Beneath it the letters O.U.O.S.V.A.V.V. are carved, and underneath them a D and an M.

The staff at Bletchley Park, called in to cast an expert eye upon the monument, could not resist the challenge and turned to some of the surviving members of the team who had spent the second world war deciphering codes.

Viewing it for the first time Oliver Lawn, 85, one of the former employees of Bletchley Park, had no doubt that there was a secret to unravel, contained both in the picture and the inscription beneath, and probably based upon missing letters from classical texts.

Mr Lawn, a Cambridge maths graduate who was among the first civilians to be recruited to Bletchley in 1940, deciphered more than 5,000 German codes during the war, using the enigma machine.

He and his colleagues helped to divert German bombers from British cities by breaking the codes that set the radio beams the Nazis used to lead their planes to the target. The successes of the decipherers is thought to have shortened the war by two years.

Their work was so secretive that it was not until recently that Mr Lawn's wife, Sheila, another Bletchley veteran, discovered what his role had been.

But while Mr Lawn normally succeeded in cracking the German wartime codes, he believes the enigma of Shugborough's monument will not be unravelled easily.

"It is totally different in terms of difficulty to what I used to do during the war," he said. "I think you need classical knowledge as well as ingenuity. This is a language rather than a mathematical code.

"Within its genre I would say it's the most challenging I have ever had to tackle. What we need is a bit more intelligence about the family from the documents held at the estate to try and find a key to breaking this. There is always a key, but if this was a code between two people and only they knew it, it could be almost impossible to decipher."

Over the years there have been a number of theories posited about the meaning contained in the Shepherd's Monument. Chief among these is the belief that the connections of the estate's creators, the Anson family, with the grand masters of the closed society of Knights Templar, and the supernatural myths surrounding the estate - where lay lines meet, rivers cross and UFO spotters regularly gather - are evidence that the carving holds the secret to the Holy Grail.

Other solutions are more prosaic. The current Lord Lichfield's great-grandmother believed the letters represented the lines of a poem from Roman mythology about a shepherdess: "Out of your own sweet vale Alicia vanish vanity twixt Deity and man, thou shepherdess the way."

There is always the possibility that the letters mean very little. Richard Kemp, the estate's general manager, said: "They could of course be a family secret, which everyone in the family knows about and which is of little consequence. But it's like Everest, you climb it because it's there. There's a code here, so everyone wants to unravel it."