Mines and Collieries Act

A serious accident in 1838 at Huskar Colliery in Silkstone, revealed the extent of child labour in the mines. A stream overflowed into the ventilation drift after violent thunderstorms causing the death of 26 children (11 girls aged from 8 to 16 and 15 boys between 9 and 12 years of age). The story of the accident appeared in London newspapers and Queen Victoria put pressure on her prime minister, Lord Melbourne, to hold an enquiry into the working conditions in Britain’s factories and mines. (1)

The investigation was chaired by Anthony Ashley-Cooper (Lord Ashley) and over the next couple of years interviewed a large number of people working in Britain's factories and mines. This included eight-year-old Sarah Gooder: "I'm a trapper in the Gawber pit. It does not tire me, but I have to trap without a light and I'm scared. I go at four and sometimes half past three in the morning, and come out at five and half past (in the afternoon).. I never go to sleep. Sometimes I sing when I've light, but not in the dark; I dare not sing then. I don't like being in the pit.... I would like to be at school far better than in the pit." (2)

Lord Ashley also discovered the problem of women working in the mines. Where possible, wagons carrying coal, were drawn by horses, and driven by children. However, in low and narrow underground passages, women were used to pull carts full of coal: Betty Harris, worked in a pit in Little Bolton in Lancashire: "I have a belt round my waist, and a chain passing between my legs, and I go on my hands and feet... I have drawn till I have had the skin off me; the belt and chain is worse when we are in the family way." Ann Eggley was employed at Thorpe's Colliery: "The work is far hard for me. Sometimes when we get home at night we have not power to wash ourselves... Father said last night it was both a shame and disgrace for girls to work as we do, but there is nothing else for us to do." (3)

Financial circumstances meant that women continued to do this work while they were pregnant. Betty Wardle explained how she had worked in a pit since she was six years old. One of her children was born while she was underground. "I had a child born in the pits, and I brought it up the pit-shaft in my skirt." When the interviewer questioned the truth of this statement, she replied: "Ay, that I am; it was born the day after I was married, that makes me to know." (4)

Isabel Wilson was 38 years old when she gave evidence to the Children's Employment Commission: "When women have children... they are compelled to take them down early. I have been married 19 years and have had 10 bairns (children); seven are in life. I was a carrier of coals, which caused me to miscarry five times from the strains, and was ill after each. My last child was born on Saturday morning, and I was at work on the Friday night." (5)

Thomas Wilson, the owner of three collieries in the Barnsley area blamed the miners for the problem. "The employment of females of any age in and about the mines is most objectionable, and I should rejoice to see it put an end to; but in the present feeling of the colliers, no individual would succeed in stopping it in a neighbourhood where it prevailed, because the men would immediately go to those pits where their daughters would be employed... The only way effectually to put an end to this and other evils in the present colliery system is to elevate the minds of the men; and the only means to attain this is to combine sound moral and religious training and industrial habits with a system of intellectual culture much more perfect than can at present be obtained by them."

Wilson warned against the idea that the government should pass legislation to protect these women: "I object on general principles to government interference in the conduct of any trade, and I am satisfied that in mines it would be productive of the greatest injury and injustice. The art of mining is not so perfectly understood as to admit of the way in which a colliery shall be conducted being dictated by any person, however experienced, with such certainty as would warrant an interference with the management of private business. I should also most decidedly object to placing collieries under the present provisions of the Factory Act with respect to the education of children employed therein." (6)

Wilson warned against the idea that the government should pass legislation to protect these women: "I object on general principles to government interference in the conduct of any trade, and I am satisfied that in mines it would be productive of the greatest injury and injustice. The art of mining is not so perfectly understood as to admit of the way in which a colliery shall be conducted being dictated by any person, however experienced, with such certainty as would warrant an interference with the management of private business. I should also most decidedly object to placing collieries under the present provisions of the Factory Act with respect to the education of children employed therein." (6)

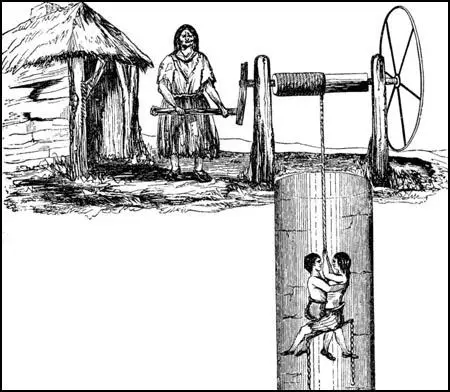

The Children's Employment Commission published its first report on mines and collieries in 1842. The report caused a sensation when details appeared in newspapers. Ivy Pinchbeck pointed out: "A wider interest was secured for the Report by the woodcuts, since they captured the imagination of many who might not have been tempted to read an ordinary Blue Book. Almost more than by their heavy labour, Victorian England was shocked and horrified by accounts of the naked state of some of the workers." (7)

The majority of people in Britain were unaware that women and children were employed as miners. However, nearly three-quarters of the petitions to Parliament were against the proposed regulation of child labour. As many as 86 per cent of petitions came from the technologically backward districts where higher levels of child labour existed and employer's feared that the change of law would lead to lower profits. (8)

Within a week of the report being published Lord Ashley gave notice of the Mines and Collieries Bill that he intended to take through Parliament. He wrote in his diary: "The government cannot, if they would refuse the bill of which I have given notice, to exclude females and children from the coal-pits - the feeling in my favour has become quite enthusiastic; the press on all sides is working most vigorously." (9)

Ashley introduced his Bill in a long eloquent speech. "Their labour... is wasteful and ruinous to themselves and their families... They know nothing that they ought to know, they are rendered unfit for the duties of women by overwork, and become utterly demoralized. In the male the moral effects of the system are very sad, but in the female they are infinitely worse, not alone upon themselves, but upon their families, upon society, and, I may add, upon the country itself. It is bad enough if you corrupt the woman, you poison the waters of life at the very fountain." (10)

Two days later he wrote in his diary: "On the 7th, I brought forward my motion - the success has been wonderful, yes, really wonderful - for two hours the House listened so attentively you might have heard a pin drop, broken only by loud and repeated marks of approbation - at the close a dozen members at least followed in succession to give me praise, and express their sense of the holy cause... Many men, I hear shed tears." (11)

Charles Vane, 3rd Marquess of Londonderry, an owner of several collieries, led the opposition in the House of Lords. He presented a petition put forward by the Yorkshire Coal-Owners Association: "With respect to the age at which males should be admitted into mines, the members of this association have unanimously agreed to fix it at eight years... In the thin coal mines it is more especially requisite that boys, varying in age from eight to fourteen, should be employed; as the underground roads could not be made of sufficient height for taller persons without incurring an outlay so great as to render the working of such mines unprofitable". Londonderry declared that some seams of coal required the employment of children; and certain pits, which could not afford to pay men's wages must either employ children or close down. (12)

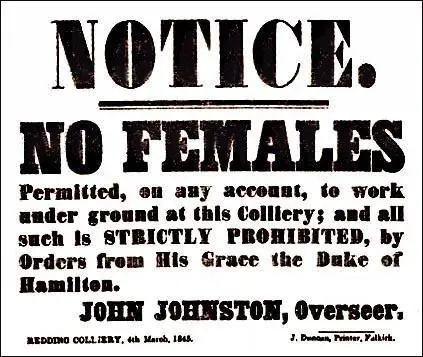

The measure was passed by the House of Lords on 5th July, 1842. However, it was amended to increased the lowest age of the boys who could work underground from 10 to 13. As a result of this legislation all females were banned from working in the collieries. However, only one inspector was appointed for the entire country and so colliery owners continued to employ women and children in mines. The inspector later admitted that he would only enforce the regulations where a child had been killed in the underground accident. Even then, the fines imposed would often fall "not upon the colliery owner, but upon the father or the guardian of the boy". (13)

In 1850 the Commissioner of Mines, Hugh Seymour Tremenheere, estimated that "200 women and girls were still working in collieries in South Wales, many of whom were only eleven or twelve years of age". (14) The government therefore increased the number of inspectors. However, Lord Ashley admitted that underground inspection was "altogether impossible, and, indeed, if it were possible it would not be safe... I for one, should be very loath to go down the shaft for the purpose of doing some act that was likely to be distasteful to the colliers below". (15) In his report of 1854, Tremenheere, reported "two instances where persons attempted inspection of their own accord, were maltreated, and very nearly lost their lives." (16)

Another difficulty was that parish records of baptisms did not contain a record of birth dates, "This posed huge problems for the inspectors who were frequently presented with unofficial and often falsified forms of evidence by parents... Some suggested the examination of children's teeth as a guide to the ages of applicants, whereas others urged the use of statistical evidence of average heights. Nothing could prevent the frequent practice of parents fraudulently presenting older siblings in order to obtain certificates for their younger offspring." (17)

Peter Kirby, the author of Child Labour in Britain, 1750-1870 (2003), has pointed out that many mine owners stopped employing young children, not because it was illegal, but because they were considered to be inefficient. "In the complicated ventilation systems of larger pits, young and inexperienced 'trappers' were often held responsible for causing explosions by leaving open their ventilation doors, and the exclusion of the very young children from complex ventilation systems, where it was applied, had a tangible effect in reducing accidents from explosions."

He then goes onto argue that "in less advanced colliery districts, where pits were small or where haulage in narrow seams was necessary and demand for child workers relatively higher, colliery owners were afforded virtual immunity from inspection and prosecution under the Act." In other words, "the Mines Act tended to be applied only where it was in the interests of colliery owners". (18)

It was not until 1872 that the age of boys who could work in the coalmines was raised to 12 and eventually to 13 in 1903. Even so, there is a great deal of evidence to show that colliery owners continued to employ children illegally for many years afterwards. (19)

Primary Sources

(1) The testimony of Betty Harris, aged 37, appeared in The Physical and Moral Condition of the Children and Young Persons employed in Mines and Manufactures (1843)

I was married at 23 and went into a colliery when I was married. I used to weave when about 12 years old, and can neither read nor write. I work to Andrew Knowles, of Little Bolton, and make sometimes about 7s. a week, sometimes not so much. I am a drawer, and work from six o'clock in the morning to six at night. stop about an hour at noon to eat my dinner: I have bread and butter for dinner; I get no drink. I have two children, but they are too young to work. I worked at drawing when I was in the family way. I know a woman who has gone home and washed herself, taken to her bed, been delivered of a child, and gone to work again under a week. I have a belt round my waist, and a chain passing between my legs, and I go on my hands and feet. The road is very steep, and we have to hold the rope; and, where there is no rope, by anything we can catch hold of. There are six women and about six boys and girls in the pit I work in; it is very hard work for a woman. The pit is very wet where I work, and the water comes over the clog-tops always, and I have seen it up to my thighs: it rains in at the roof terribly; my clothes were wet through almost all day long. I never was ill in my life but when I was lying-in. My cousin looks after the children in the day-time, I am very tired when I get home at night; I fall asleep sometimes before I get washed. I am not so strong as I was, and cannot stand my work so well as I used to do. I have drawn till I have had the skin off me: the belt and chain is worse when we are in the family way. My feller [husband] has beaten me many a time for not being ready. I were not used to it at first, and he had little patience: I have known many a man beat his drawer. I have known men take liberties with the drawers, and some of the women have bastards. I think it would be better if we were paid once a week instead of once a month, for then I would buy victuals with ready money. It is bad to live on 7s., and rent 1s. 6d.

I have been hurt once: I got on a waggon of coals in the pit to get out of the way of the next waggon, and the waggon I was on went off before I could get off, and crushed my bones about the hips between the roof and the coals: I was ill 23 weeks. Mr. Fitzgerald and Mr. Fletcher will not have Mr. women in the pits. I have heard of knocks or joults: I had my arm broken by a waggon; I had gotten all out of the road by my arm. and it broke my arm.

The women are frequently wicked, and swear dreadfully at the bottom of the pit at each other, about their turn to hook-on. They are like to stand up for themselves; keeping one from hooking-on is like taking the meat out of one's mouth. There are some women that go to church regularly, and some that does not. Women with a family can seldom go to church. Some have a mother to look after. Collier's houses are generally ill off for furniture. I have a table and a bed, and I have a tin kettle to boil potatoes in. I wear a pair of trousers and a jacket, and am very hot when working, but cold when standing still. They beat the children badly; if they are very little they get beat. There is a great deal on managing a house; some can manage better than others; those that can write and have been properly taught can manage best. My husband can read and write.

(2) Betty Wardle, Children's Employment Commission Report (1842)

Q: Have you ever worked in a coal pit?

A: Ay, I have worked in a pit since I was six years old.

Q: Have you any children?

A: Yes, I have four children; two of them were born while I worked in the pits.

Q: Did you work in the pits whilst you were in the family way?

A: Ay, to be sure. I had a child born in the pits, and I brought it up the pit-shaft in my skirt.

Q: Are you quite sure you are telling the truth?

A: Ay, that I am; it was born the day after I was married, that makes me to know.

Q: Did you draw with the belt and chain?

A: Yes, I did.

(3) Children's Employment Commission Report (1842)

The chief miners, the undergoers, were lying on their sides, and with their picks were clearing away the coal to a height of a little more than two feet. Boys were employed in clearing out what the men had disengaged... Children were chained, belted, harnessed like dogs in a go-cart, black, saturated with wet, and more than half-naked - crawling upon their hands and feet, and dragging their heavy loads behind them - they present an appearance indescribably disgusting and unnatural.

(4) Isabel Wilson, 38 years old, Children's Employment Commission Report (1842)

When women have children... they are compelled to take them down early. I have been married 19 years and have had 10 bairns (children); seven are in life. I was a carrier of coals, which caused me to miscarry five times from the strains, and was ill after each. My last child was born on Saturday morning, and I was at work on the Friday night.

Once met with an accident; a coal brake my cheek-bone, which kept me idle some weeks.

None of the children read, as the work is no regular. I did read once, but no able to attend to it now; when I go below lassie 10 years of age keeps house and makes the broth or stir-about.

(5) Isabel Hogg, aged 53, Children's Employment Commission Report (1842)

I have been married 37 years; it was the practice to marry early, when the coals were all carried on women's backs, men needed us; from the great sore labour false births are frequent and very dangerous.

I have four daughters married, and all work below till they bear their bairns (children) - one is very badly now from working while pregnant, which brought on a miscarriage from which she is not expected to recover.

Collier-people suffer much more than others - my good man died nine years since with bad breath; he lingered some years and was entirely off work 11 years before he died.

You must just tell the Queen Victoria that we are good loyal subjects; women-people here don't mind work, but they object to horse-work; and that she would have the blessings of all the Scotch coal-women if she would get them out of the pits, and send them to other labour.

Student Activities

The Coal Industry: 1600-1925 (Answer Commentary)

Women in the Coalmines (Answer Commentary)

Child Labour in the Collieries (Answer Commentary)

Child Labour Simulation (Teacher Notes)

The Chartists (Answer Commentary)

Women and the Chartist Movement (Answer Commentary)

Road Transport and the Industrial Revolution (Answer Commentary)

Canal Mania (Answer Commentary)

Early Development of the Railways (Answer Commentary)

Health Problems in Industrial Towns (Answer Commentary)

Public Health Reform in the 19th century (Answer Commentary)

Richard Arkwright and the Factory System (Answer Commentary)

Robert Owen and New Lanark (Answer Commentary)

James Watt and Steam Power (Answer Commentary)

The Domestic System (Answer Commentary)

The Luddites: 1775-1825 (Answer Commentary)

The Plight of the Handloom Weavers (Answer Commentary)

1832 Reform Act and the House of Lords (Answer Commentary)

Benjamin Disraeli and the 1867 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)

William Gladstone and the 1884 Reform Act (Answer Commentary)