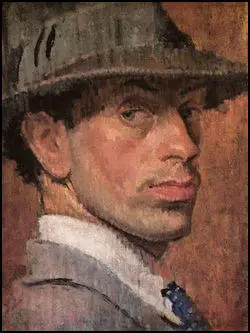

Isaac Rosenberg

Isaac Rosenberg, the second child and second son in the family of four sons and two daughters, of Jewish immigrants, was born in Bristol on 25th November 1890. His father was a pedlar and his mother took in washing. In 1897 the family moved to London.

John Carey has pointed out: "The first London home they found for themselves and their five children was a single room behind a rag-and-bone shop in Tower Hamlets. Later they moved to a ground-floor and basement in Whitechapel. Isaac had a twin brother who died soon after birth, and he was so small a baby that, as his mother enjoyed recalling, 'you could have put him in a jug'. Like many slum children, Isaac grew up stunted and with a weak chest. He started school aged eight, unable to read or write English, but reached the required grade in the three Rs within a year, and moved to one of the board schools established under the 1870 Education Act." After being educated in East End council schools, Rosenberg left at fourteen and became an apprentice engraver, a job that he hated. In the evenings he read the works of Lord Byron, Percy Bysshe Shelley, John Keats and William Blake.

Rosenberg was an accomplished watercolourist and with the help of the Jewish Education Aid Society and the private Jewish benefactors, including Lily Joseph, he spent time studying art at the Stepney Green Crafts School and Birkbeck College. In 1911 he became a student at the Slade School of Fine Art. During this period Rosenberg became friends with the David Bomberg, Mark Gertler, William Roberts, C. R. W. Nevinson, Stanley Spencer, John Rodker, Stephen Winstein, and Joseph Lefkowitz and formed what became known as the Whitechapel Group. They met at Whitechapel Reference Library and used to go for all-night walks in Epping Forest. Rosenberg wrote: "‘Art is not a plaything, it is blood and tears, it must grow up with one; and I believe I have begun too late."

As well as painting, Rosenberg also wrote poetry. Suffering from poor health, Rosenberg emigrated to the warmer climate of South Africa. In Cape Town he lectured on art, painted portraits and had some of his poems published in South African magazines. He also made friends with the writer Olive Schreiner.

Rosenberg missed London and in February 1915 returned to England. He published a collection of poems, Youth, but was deeply upset when he discovered that only ten copies of his book had been sold. In October 1915 Rosenberg joined the Bantams, a special battalion for men too short to be accepted into other regiments.

Sent to the Somme in France, Rosenberg was on the Western Front for the next two years. While in the trenches he wrote several poems including Break of Day in the Trenches, considered by Paul Fussell (The Great War and Modern Memory) as the greatest poem to come out of the First World War. The critic, Jon Stallworthy, wrote: "Rosenberg's poems from the front show him to have absorbed the great tradition of English pastoral poetry, but his tone is different: more impersonal, informal, ironic, and lacking the indignation characteristic of the work of Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon." Stallworthy claims that Rosenberg succeeded in his intention of writing "Simple poetry - that is where an interesting complexity of thought is kept in tone and right value to the dominating idea so that it is understandable and still ungraspable".

Isaac Rosenberg was killed by a German raiding party on 1st April, 1918. His body was never recovered and the headstone in the Bailleul Road East military cemetery in France stands over an empty grave. Rosenberg's friends arranged for his poems, Collected Works to be published in 1922.

The First World War (£4.95)

Primary Sources

(1) Isaac Rosenberg, In The Trenches (1916)

I snatched two poppies

From the parapet’s ledge,

Two bright red poppies

That winked on the ledge.

Behind my ear

I stuck one through,

One blood red poppy

I gave to you.

The sandbags narrowed

And screwed out our jest,

And tore the poppy

You had on your breast ...

Down - a shell - O! Christ,

I am choked ... safe ... dust blind, I

See trench floor poppies

Strewn. Smashed you lie.

(2) Isaac Rosenberg, Break of Day in the Trenches (1916)

The darkness crumbles away.

It is the same old druid Time as ever,

Only a live thing leaps my hand,

A queer sardonic rat,

As I pull the parapet's poppy

To stick behind my ear.

Droll rat, they would shoot you if they knew

Your cosmopolitan sympathies.

Now you have touched this English hand

You will do the same to a German

Soon, no doubt, if it be your pleasure

To cross the sleeping green between.

It seems you inwardly grin as you pass

Strong eyes, fine limbs, haughty athletes,

Less chanced than you for life,

Bonds to the whims of murder,

Sprawled in the bowels of the earth,

The torn fields of France.

What do you see in our eyes

At the shrieking iron and flame

Hurled through still heavens ?

What quaver - what heart aghast?

Poppies whose roots are in man's veins

Drop, and are ever dropping;

But mine in my ear is safe -

Just a little white with the dust.

(3) Isaac Rosenberg, Returning, We Hear The Larks (1917)

Sombre the night is.

And though we have our lives, we know

What sinister threat lies there.

Dragging these anguished limbs, we only know

This poison-blasted track opens on our camp -

On a little safe sleep.

But hark! joy - joy - strange joy.

Lo! heights of night ringing with unseen larks.

Music showering our upturned list’ning faces.

Death could drop from the dark

As easily as song -

But song only dropped,

Like a blind man’s dreams on the sand

By dangerous tides,

Like a girl’s dark hair for she dreams no ruin lies there,

Or her kisses where a serpent hides.

(4) Isaac Rosenberg, The Immortals (1918)

I killed them, but they would not die.

Yea! all the day and all the night

For them I could not rest or sleep,

Nor guard from them nor hide in flight.

Then in my agony I turned

And made my hands red in their gore.

In vain - for faster than I slew

They rose more cruel than before.

I killed and killed with slaughter mad;

I killed till all my strength was gone.

And still they rose to torture me,

For Devils only die in fun.

I used to think the Devil hid

In women’s smiles and wine’s carouse.

I called him Satan, Balzebub.

But now I call him, dirty louse.

(5) John Carey, Sunday Times (13th April, 2008)

Which of all the British poets came from the most deprived background? Thomas Traherne? William Blake? John Clare? Robert Burns? Almost certainly the correct answer is Isaac Rosenberg, who was born into a family of Yiddish-speaking Lithuanian Jewish immigrants in 1890. His father was a pedlar; his mother took in washing and sold fancy needlework. The first London home they found for themselves and their five children was a single room behind a rag-and-bone shop in Tower Hamlets. Later they moved to a ground-floor and basement in Whitechapel. Isaac had a twin brother who died soon after birth, and he was so small a baby that, as his mother enjoyed recalling, “you could have put him in a jug”. Like many slum children, Isaac grew up stunted and with a weak chest. He started school aged eight, unable to read or write English, but reached the required grade in the three Rs within a year, and moved to one of the board schools established under the 1870 Education Act. In effect, it was a Jewish school within the state system, and he learnt some Hebrew and Old Testament history. But the education was basic at best (no foreign languages, no music) and he had to leave to earn his living at 14, getting a job in an etching workshop, which he hated.

His literary and artistic gifts became apparent early on. His sisters remember him writing poems in bed by the light of a candle, and sketching complete strangers on street corners. His studio was the kitchen table, littered with cups and plates. By the time he was 11, he had become an accomplished watercolourist, and efforts began to be made on his behalf, driven by community spirit, family solidarity and an earnest belief in education - all of them things we seem to have abandoned. The Jewish Education Aid Society took a hand, so did his teachers and private Jewish benefactors. Means were found to send him to Stepney Green Crafts School for one day a week, then to evening classes at Birkbeck College, and, in 1911, to the Slade School of Fine Art. Most of his fellow students were upper middle class, and their recollections of him focus on his “appalling cockney accent”, bad adenoids and “shocking teeth”. He tried reading them his poems, but they bombarded him with paper pellets, and when he lent some of them his studio they smashed it up in a fit of high jinks.

He made friends with the painters David Bomberg and Mark Gertler and, together with the poet and publisher John Rodker and the dancer and actress Sonia Cohen, they formed the nucleus of what became known as the Whitechapel Group. They would meet in the Whitechapel reference library, which was warmer and better lit than their homes, and go for all-night walks in Epping forest, talking of “life, death, youth and love”. Jewish, educated at board schools, and forced to work long hours at menial jobs, they were, as Jean Moorcroft Wilson points out, the polar opposite of the privileged and largely anti-semitic Bloomsbury Group....

Unlike the more famous war poets, he did not become an officer. Posted at first to a Bantam battalion, for men under 5ft 3in in height, he moved fairly rapidly from unit to unit, accompanied by complaints that he was unsoldierly and neglectful of his duties, which was another way of saying that he had the courage to resist the military machine. “I am determined,” he wrote, “that this war, with all its powers for devastation, shall not master my poeting.”

He showed his intransigence in his poetry, as in all else. Even his friends and admirers were daunted by its obscurities and contortions, which sometimes suggest an imperfect grasp of English usage. Yet he could also write with brilliant clarity, as in Break of Day in the Trenches, which Paul Fussell in The Great War and Modern Memory selected as the greatest poem to come out of that monstrous slaughter. Poised and ironic, it expresses Rosenberg's sense of detachment as he addresses a “queer sardonic rat” that has touched his hand as he plucks a poppy from the trench parapet to tuck behind his ear, and that may go on to touch German hands: “Droll rat, they would shoot you if they knew/ Your cosmopolitan sympathies.”