Geoffrey Studdert Kennedy

Geoffrey Studdert Kennedy, the seventh of nine children, was born in Leeds on 27th June, 1883. His parents were Jeanette Anketell and William Studdert Kennedy, the vicar of St Mary's Quarry Hill, Leeds. Educated at Leeds Grammar School and Trinity College, Dublin, Studdert Kennedy graduated in classics and divinity in 1904. After a year's training at Ripon Clergy College, he became a curate in Rugby and in 1914 the vicar of St. Paul's, Worcester.

On the outbreak of the First World War Studdert Kennedy volunteered to become an a chaplain to the armed forces on the Western Front. Given the nickname Woodbine Willie, for his habit of distributing cigarettes to soldiers, he was loved and respected by the men for his bravery under fire.

Arthur Savage met Kennedy while on the front-line: "Kennedy, an army chaplin he was and he'd come down into the trenches and say prayers with the men, have a cuppa out of a dirty tin mug and tell a joke as good as any of us. He was a chain smoker and always carried a packet of Woodbine cigarettes that he would give out in handfuls to us lads. That's how he got his nickname. He came down the trench one day to cheer us up. Had his Bible with him as usual. Well, I'd been there for weeks, unable to write home, of course, we were going over the top later that day. I asked him if he would write to my sweetheart at home, tell her I was still alive and, so far, in one piece. He said he would, so I gave him the address. Well, years later, after the war, she showed me the letter he'd sent, very nice it was. A lovely letter. My wife kept it until she died."

In 1917 Studdert Kennedy won the Military Cross at Messines Ridge after running into No-Mans-Land to provide comfort to those injured during an attack on the German frontline. He wrote several poems about his experiences and these appeared in the books, Rough Rymes of A Padre (1918) and More Rough Rhymes (1919).

In 1922 Studdert Kennedy was appointed to run St Edmund King and Martyr in Lombard Street, London. His experiences during the war had converted him to Christian Socialism and pacifism, and he wrote about his beliefs in several books including Lies (1919), Democracy and the Dog-Collar (1921), Food for the Fed Up (1921), The Wicket Gate (1923) and The Word and the Work (1925).

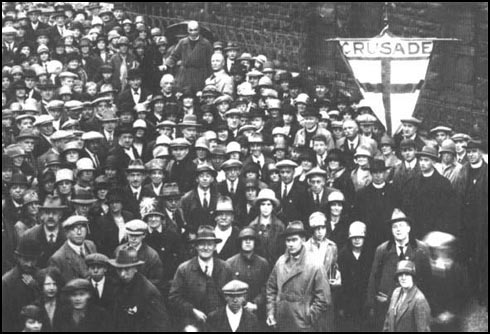

during an Industrial Christian Fellowship Crusade in 1928.

Studdert Kennedy also worked for the Industrial Christian Fellowship (ICF) and this involved him in public speaking tours of Britain. In 1928 a newspaper reported that his sermons were so emotional that at his packed meetings "women wept and men broke down".

Geoffrey Studdert Kennedy was taken ill during an ICF crusade in Liverpool and died on 8th March, 1929. Arthur Savage later recalled: "He worked in the slums of London after the war among the homeless and the unemployed. The name Woodbine Willie was known to everyone in the land in those days. Died very young, he did, and at his funeral people placed packets of Woodbine cigarettes on his coffin and his grave as a mark of respect and love."

Primary Sources

(1) While on the Western Front, Private Arthur Savage met Rev. Studdert Kennedy.

A man I recall with great affection was Woodbine Willie. His proper name was Reverend Studdert Kennedy, an army chaplin he was and he'd come down into the trenches and say prayers with the men, have a cuppa out of a dirty tin mug and tell a joke as good as any of us. He was a chain smoker and always carried a packet of Woodbine cigarettes that he would give out in handfuls to us lads. That's how he got his nickname. At Mesines Ridge he ran out into no man's land under murderous machine-gun fire to tend the wounded and dying. Every man was carrying a gun except him. He carried a wooden cross. He gave comfort to dying Germans as well. He was awarded the Military Cross and he deserved it.

He came down the trench one day to cheer us up. Had his Bible with him as usual. Well, I'd been there for weeks, unable to write home, of course, we were going over the top later that day. I asked him if he would write to my sweetheart at home, tell her I was still alive and, so far, in one piece. He said he would, so I gave him the address. Well, years later, after the war, she showed me the letter he'd sent, very nice it was. A lovely letter. My wife kept it until she died.

He worked in the slums of London after the war among the homeless and the unemployed. The name Woodbine Willie was known to everyone in the land in those days. Died very young, he did, and at his funeral people placed packets of Woodbine cigarettes on his coffin and his grave as a mark of respect and love.