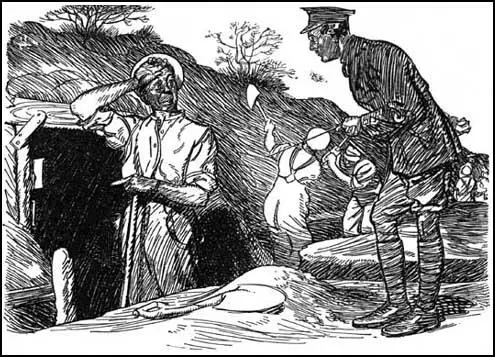

Dugouts

Dugouts were protective holes dug out of the sides of trenches. The size of dugouts varied a great deal and sometimes could house over ten men. A manual published by the British Army recommended dugouts that were between 2 ft. and 4 ft. 6 in. wide, roofed with corrugated iron or brushwood and then covered with a minimum of 9 inches of earth.

Frank Percy Crozier was shocked by the first dug-out he encountered: "It is a deep dug-out which has been allocated to me for my use. It needs to be deep to keep out heavy stuff.... I find the place full of dead and wounded men. It has been used as a refuge. None of the wounded can walk. There are no stretchers. Most are in agony. They have seen no doctor. Some have been there for days. They have simply been pushed down the steep thirty-feet-deep entrance out of further harm's way and left - perhaps forgotten. As I enter the dugout I am greeted with the most awful cries from these dreadfully wounded men."

Guy Chapman also complained about his dug-out: "Our dugout, a cellar at the trench corner, was not gas-proof nor had it much head cover. Rats, great beasts as big as kittens, which ran to and fro over the parapets and squeaked behind the boards in the dugout shafts. Dell was their deadly enemy. With an "Excuse me, sir," he would brush by me and lunge with his bayonet at a scurrying shadow. Not infrequently, he would turn back to me waving a struggling trophy, which torchlight revealed as the scrofulous and mangy progenitor of vast litters, now, gorged on French corpses and offal, too obese to move with the slippery agility of the young fry."

As the war went on dugouts grew in size. By 1917 dugouts at Messines could hold two battalions of soldiers at a time. Large dugouts were also built into the side of communication trenches so that they were not directly in line of fire from enemy guns. These often served as the battalion headquarters and provided sleeping accommodation for the officers.

Primary Sources

(1) George Coppard, With A Machine Gun to Cambrai (1969)

On my frequent visits to company HQ I saw the kind of life the officers led when not in the front line or on patrol. Their greatest comfort was sleeping-bags and blankets, and room to stretch out for sleep. Batmen were handy to fetch and carry. Meals and drinks were prepared and placed before them. In addition to rum, whisky was also available. Cartoons and pin-ups decorated the walls, and there was never a lack of the precious weed. Such things, and many other small trifles, demonstrated the great difference between the creature comforts of the officers, and the almost complete absence of them for the men. That's what the war was like.

(2) Philip Gibbs, The Pageant of the Years (1946)

The cheery optimism of our generals always thought we were going forward, and therefore it was not worth while making ourselves comfortable and safe. We never made a dugout worthy of the name. But the Germans worked like beavers, and after their retreat I went down into dugouts, forty feet deep, connected with passages and with separate exists. Many of them were panelled, and had excellent bathrooms for the officers with a little gadget where the gentleman in the bath might place his cigar during his ablutions - a very German idea.

(3) Manchester Guardian (17th October, 1914)

Our men have made themselves fairly comfortable in the trenches, in the numerous quarries cut out of the hillsides, and in the picturesque villages whose steep streets and red-tiled roofs climb the slopes and peep out amid the green and russet of the woods.

In the firing line the men sleep and obtain shelter in the dug-outs they have hollowed or "undercut" in the sides of the trenches. These refuges are slightly raised above the bottom of the trench, so as to remain dry in wet weather. The floor of the trench is also sloped for the purpose of drainage. Some trenches are provided with head cover, and others with overhead cover, the latter, of course, giving protection from the weather as well as from shrapnel balls and splinters of shell.

(4) Guy Chapman, A Passionate Prodigality: Fragments of Autobiography (1933)

Our dugout, a cellar at the trench corner, was not gas-proof nor had it much head cover. Rats, great beasts as big as kittens, which ran to and fro over the parapets and squeaked behind the boards in the dugout shafts. Dell was their deadly enemy. With an "Excuse me, sir," he would brush by me and lunge with his bayonet at a scurrying shadow. Not infrequently, he would turn back to me waving a struggling trophy, which torchlight revealed as the scrofulous and mangy progenitor of vast litters, now, gorged on French corpses and offal, too obese to move with the slippery agility of the young fry.

(5) Private Jack Sweeney, Lincolnshire Regiment, letter (1916)

I have a nice dug-out where I cook and after the officers have had their dinner I let as many of the boys who are not on duty come in and have a warm and I make them a drop of hot tea, the officers get plenty of food, they waste a lot but the boys are glad to eat all they leave. The boys are so happy when they can have a warm and makes me feel happy to be able to give them a little comfort - you should see the steam rising off their clothing it is the only way they can get their clothes dry.

(6) Private Frank Bass, letter (1916)

In one of the dug-outs the other night, two men were smoking by the light of the candle, very quiet. All at once the candle moved and flickered. Looking up they saw a rat was dragging it away. Another day I saw a rat washing itself like a cat behind the candle. Some as big as rabbits. I was in the trench the other night and one jumped over the parapet.

(7) Charles Hudson, journal entry, quoted in Soldier, Poet, Rebel (2007)

I was sitting in my company headquarters, a corrugated-iron topped shelter cut into the sandbagged parapet, when heavy shelling was concentrated on the remains of a derelict building incorporated in our company sector. One of my platoon commanders, a lad of about 19, was with me. Odd shells were bursting in our vicinity, and the platoon commander, obviously hoping I would advise against it, said, "I suppose I ought to go to my platoon."

This was the first time of many that I had to face the unpleasant responsibility of telling a subordinate to expose himself to a very obvious odds-on chance of being killed. I told him he ought to join his platoon. He had no sooner gone than I heard that haunting long drawn-out cry "stretcher-bearers", to which the men in the trenches were so addicted.

I followed him out, glad of the spur to action. It is so easy to find sound reasons for keeping undercover in unpleasant circumstances. Three company stretcher-bearers were hurrying down the trench. Stretcher-bearers were wonderful people. Ours had been the bandsmen of earlier training days. They were always called to the most dangerous places, where casualties had already taken place, yet there were always men ready to volunteer for the job, at any rate in the early days of the war. The men were not bloodthirsty. Stretcher-bearers were unarmed and though they were not required to do manual labour or sentry-go, this I am sure was not the over-riding reason for their readiness to volunteer.

I had not yet learned that a few casualties always seemed to magnify themselves to at least three times the number they really are and I was filled with horror when I reached the derelict house. A shelter had received a direct hit. I found the subaltern unhurt and frantically engaged in trying to dig out the occupants. The shells were bursting all round the area as I approached, and men cowering undercover were shouting at me to join them. Dust from the shattered brickwork and torn sandbags was flying and this, and the unpleasant evil-smelling fumes from the shells made it difficult to realise what was going on. A man close by me was hit and I began to tend him as a stretcher bearer came to help me. More shells burst almost on top of us. I noticed how white the men were, and I wondered if I was as white as they were.

Their evident fear strengthened my own nerves. We had been lectured on trench warfare, and it suddenly and forcibly struck me that this bombardment might well be a preliminary to a trench raid. At any moment the shelling might lift and almost simultaneously we might find enemy infantry on top of us. I shouted for the subaltern.

"Were any sentries on the lookout" I demanded. I stormed at the men and drove the sentries back on to the parapet. The reserve ammunition had been hit and I cursed the subaltern for not having done anything about replenishment. After this outburst. and in a calmer state of mind, I went from post to post warning the men to be on the lookout. Gradually the shellfire slackened and finally ceased.

That night I found myself physically and mentally exhausted. I determined at least not to try and overcome tears with whisky. I wondered too whether the soldiers, when they had recovered, would regard me as having been "windy". The word was much used by those who had been at the front some time and, like all soldiers' slang, it caught on very quickly with the newcomers.

Once damned with "windiness", an officer lost much of the respect of the men and with it his power of control. Had I in fact been unnecessarily windy? I knew in my heart of hearts that I had, though I found out later that my behaviour had not given that impression. It is comparatively easy for an officer to control himself because he has more to occupy his mind than the men. I resolved in future to think more and talk (or shout) less in an emergency.

(8) A.A. Milne, It's Too Late Now: The Autobiography of a Writer (1939)

We sat there completely isolated. The depth of the dugout deadened the noise of the guns, so that a shell-burst was no longer the noise of a giant plumber throwing down his tools, but only a persistent thud, which set the candles dancing and then, as if by an afterthought, blotted them out. From time to time I lit them again, wondering what I should be doing, wondering what signalling officers did on these occasions. Nervously I said to the Colonel, feeling that the isolation was all my fault, `Should I try to get a line out?' and to my intense relief he said, "Don't be a bloody fool."

(9) Frank Percy Crozier, A Brass Hat in No Man's Land (1930)

It is a deep dug-out which has been allocated to me for my use. It needs to be deep to keep out heavy stuff. The telephone lines are all cut by shell fire. Kelly, a burly six-feet-two-inches high Irish Nationalist, has been sent in a week before to look after emergency rations. He has endured the preliminary bombardment for a week already with the dead and dying, during which time he has had difficulty in going outside, even at night and then only between the shells. A wrong thing has been done. I find the place full of dead and wounded men. It has been used as a refuge. None of the wounded can walk. There are no stretchers. Most are in agony. They have seen no doctor. Some have been there for days. They have simply been pushed down the steep thirty-feet-deep entrance out of further harm's way and left - perhaps forgotten. As I enter the dugout I am greeted with the most awful cries from these dreadfully wounded men. Their removal is a Herculean task, for it was never intended that the dying and the helpless should have to use the deep stairway. After a time, the last sufferer and the last corpse are removed. Meanwhile I mount the parapet to observe. The attack on the right has come to a standstill; the last detailed man has sacrificed himself on the German wire to the God of War. Thiepval village is masked with a wall of corpses.