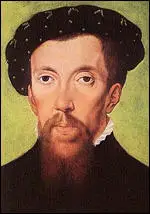

Anthony Denny

Anthony Denny, the second son of Sir Edmund Denny and Mary Troutbeck Denny, was born in Cheshunt on 16th January 1501. (1)

Denny was educated at St Paul's School, London, where his contemporaries included John Leland, William Paget and Thomas Wriothesley. (2)

Anthony Denny began his public career in the service of Sir Francis Bryan, a favourite of the king, on diplomatic missions to France, and in the late 1520s was employed in the royal household. A close associate of Thomas Cromwell he became a yeoman of the wardrobe in 1536. Later that year he arranged for his sister-in-law, Katherine Ashley, to join the household of Princess Elizabeth. (3)

On 9th February 1538, Anthony Denny married Joan Champernon. Over the next few years she gave birth to five sons and four daughters. In 1539 Anthony Denny was appointed as gentleman of the privy chamber. In this role he became very close to Henry VIII. This included having conversations with Denny about the mistake he had made in marrying Anne of Cleves. Henry told Denny that his wife was not only "not as she was reported, but had breasts so slack and other parts of body in such sort that he somewhat suspected her virginity". (4) In 1544 he accompanied the king to Boulogne, and was knighted there on 30th September. In 1545 Denny presented the king with a clock designed by Hans Holbein.

Anthony Denny - Religious Reformer

Denny's biographer, Narasingha Prosad Sil, has argued that he was a supporter of religious reform. "Most of his associates were humanists, committed to Erasmian pietism and the cause of learning, and Denny himself was moderate in the expression of his religious views, which never conflicted with his loyalty to and friendship with the king. His sympathy with the reformed faith did not prevent his taking notice of heretical books as a loyal government servant.... But of Denny's own protestant allegiance there can be no doubt." (5) A friend of Archbishop Thomas Cranmer in 1546 Denny supported the archbishop's recommendations against the "vain ceremonies" of traditional religion, and after his death was hailed as "an enemy to the Pope and his superstition". (6)

Peter Ackroyd, the author of the Tudors (2012) has argued that by 1546 Sir Anthony Denny and William Paget became important political figures and were both supporters of religious reform: "In the last months of his life access to the king had been granted by Sir Anthony Denny and William Paget, private secretary. Denny and Paget were a powerful influence upon the ailing king, and in this crucial period it is likely that they aligned themselves with the reformers in the king's council." (7)

Henry VIII died on 28th January, 1547. An executor of Henry's will, he also received a substantial bequest, quite possibly arranged by Denny himself after the king's death. (8) Edward was only nine years old and was too young to rule. In his will, Henry had nominated a Council of Regency, made up of 16 nobles and churchman to assist him in governing his new realm. This included Anthony Denny, Edward Seymour, Thomas Seymour, Thomas Cranmer, William Paget, Thomas Wriothesley and Cuthbert Tunstall. (9)

Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset, emerged as the leading figure in the government and was given the title Lord Protector. He was now arguably the most influential person in the land. (10) Edward's brother, Thomas, although he was in his late thirties, proposed to the Council that he should marry the 13-year-old, Elizabeth, but he was told this was unacceptable. He now set his sights on Catherine Parr. At the time he was described as "being gifted with charm and intelligence... and a handsome appearance". Seymour married Parr in secret in about May 1547.

Thomas Seymour and Princess Elizabeth

Catherine Parr, who was now thirty-five, became pregnant. Although she had been married three times before, it was her first pregnancy. It came as a great shock as Catherine was assumed to be "barren". (11) Thomas Seymour now began paying more attention to Elizabeth. Katherine Ashley, Elizabeth's governess, later recorded: "Seymour... would come many mornings into the Lady Elizabeth's chamber, before she were ready, and sometimes before she did rise. And if she were up, he would bid her good morrow, and ask how she did, and strike her upon the back or on the buttocks familiarly, and so go forth through his lodgings; and sometime go through to the maidens and play with them, and so go forth... If Lady Elizabeth was in bed, he would... make as though he would come at her. And he would go further into the bed, so that he could not come at her." On one occasion Ashley saw Seymour try to kiss her while she was in bed and the governess told him to "go away for shame". Seymour became more bold and would come up every morning in his nightgown, "barelegged in his slippers". (12)

According to Elizabeth Jenkins, the author of Elizabeth the Great (1958) claims that the evidence suggested that the "Queen Dowager took to coming with her husband on his morning visits and one morning they both tickled the Princess as she lay in her bed. In the garden one day there was some startling horse-play, in which Seymour indulged in a practice often heard of in police courts; the Queen Dowager held Elizabeth so that she could not run away, while Seymour cut her black cloth gown into a hundred pieces. The cowering under bedclothes, the struggling and running away culminated in a scene of classical nightmare, that of helplessness in the power of a smiling ogre... The Queen Dowager, who was undergoing an uncomfortable pregnancy, could not bring herself to make her husband angry by protesting about his conduct, but she began to realize that he and Elizabeth were very often together." (13)

| Spartacus E-Books (Price £0.99 / $1.50) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Jane Dunn has controversially argued that Elizabeth was a willing victim in these events: "Although not legally her step-father, Thomas Seymour assumed his role as head of the household and with his manly demeanour and exuberant animal spirits he became for the young Princess a charismatic figure of attraction and respect. Some twenty-five years her senior, Seymour in fact was old enough to be her father and the glamour of his varied heroic exploits in war and diplomatic dealings brought a welcome worldly masculinity into Elizabeth's cloistered female-dominated life.... Elizabeth was also attractive in her own right, tall with fair reddish-gold hair, fine pale skin and the incongruously dark eyes of her mother, alive with unmistakable intelligence and spirit. She was young, emotionally inexperienced and understandably hungry for recognition and love. She easily became a willing if uneasy partner in the verbal and then physical high jinks in the newly sexualised Parr-Seymour household." (14)

Sir Thomas Parry, the head of Elizabeth's household, later testified that Thomas Seymour loved Elizabeth and had done so for a long time and that Catherine Parr was jealous of the fact. In May 1548 Catherine "came suddenly upon them, where they were all alone, he having her (Elizabeth) in his arms, wherefore the Queen fell out, both with the Lord Admiral and with her Grace also... and as I remember, this was the cause why she was sent from the Queen." (15)

Member of the Privy Council

Sir Anthony Denny, who was now a member of the Privy Council, was now called in to deal with the situation. Princess Elizabeth went to live with him and his wife at their home at Cheshunt. It has been suggested that this was done not as punishment but as a means of protecting the young girl. Philippa Jones, the author of Elizabeth: Virgin Queen (2010) has suggested that Elizabeth was pregnant with Seymour's child. (16)

In January 1549, Denny was on the parliamentary committee which examined Thomas Seymour, accused of treason, and signed the council's order for his execution. On 20th March, 1549, Seymour was beheaded on Tower Hill. Even on the scaffold, Seymour refused to make the usual confession. Bishop Hugh Latimer commented: "Whether he be saved or no, I leave it to God, but surely he was a wicked man, and the realm is well rid of him." (17) When she heard the news, it is claimed Elizabeth commented: "This day died a man of much wit and very little judgment." (18)

Sir Anthony Denny took part in the attempt to suppress the rebellion led by Robert Kett. However, he was taken ill and died on 10th September 1549.

Primary Sources

(1) Narasingha Prosad Sil, Anthony Denny : Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-2014)

As the 1540s progressed Denny became ever closer to King Henry. He was one of the first courtiers whom Henry took into his confidence in lamenting his nuptial contract with Anne of Cleves. In 1544 he accompanied the king to Boulogne, and was knighted there on 30 September, after the city's capitulation. Denny had hitherto been junior to Sir Thomas Heneage in the privy chamber, but henceforward his influence exceeded Heneage's, especially after 20 September 1545 when Denny, along with John Gates (the husband of his sister Mary) and their assistant William Clerk, was licensed by the king to affix the royal stamp - the sign manual - on all documents emanating from the monarch. Occasioned by Henry's growing infirmity, this was a transfer of authority which gave great influence to the men who wielded it. Then in October 1546 Heneage retired from service and Denny replaced him as first chief gentleman and groom of the stool. Denny often exchanged gifts with the king. On new year's day 1537 Queen Jane Seymour gave him a gold brooch (presumably intended for his wife), and at the beginning of 1545 Denny presented the king with a clock designed by Hans Holbein.

Student Activities

Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Henry VII: A Wise or Wicked Ruler? (Answer Commentary)

Henry VIII: Catherine of Aragon or Anne Boleyn?

Was Henry VIII's son, Henry FitzRoy, murdered?

Hans Holbein and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

The Marriage of Prince Arthur and Catherine of Aragon (Answer Commentary)

Henry VIII and Anne of Cleves (Answer Commentary)

Was Queen Catherine Howard guilty of treason? (Answer Commentary)

Anne Boleyn - Religious Reformer (Answer Commentary)

Did Anne Boleyn have six fingers on her right hand? A Study in Catholic Propaganda (Answer Commentary)

Why were women hostile to Henry VIII's marriage to Anne Boleyn? (Answer Commentary)

Catherine Parr and Women's Rights (Answer Commentary)

Women, Politics and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Cardinal Thomas Wolsey (Answer Commentary)

Historians and Novelists on Thomas Cromwell (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and Thomas Müntzer (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and Hitler's Anti-Semitism (Answer Commentary)

Martin Luther and the Reformation (Answer Commentary)

Mary Tudor and Heretics (Answer Commentary)

Joan Bocher - Anabaptist (Answer Commentary)

Anne Askew – Burnt at the Stake (Answer Commentary)

Elizabeth Barton and Henry VIII (Answer Commentary)

Execution of Margaret Cheyney (Answer Commentary)

Robert Aske (Answer Commentary)

Dissolution of the Monasteries (Answer Commentary)

Pilgrimage of Grace (Answer Commentary)

Poverty in Tudor England (Answer Commentary)

Why did Queen Elizabeth not get married? (Answer Commentary)

Francis Walsingham - Codes & Codebreaking (Answer Commentary)

Codes and Codebreaking (Answer Commentary)

Sir Thomas More: Saint or Sinner? (Answer Commentary)

Hans Holbein's Art and Religious Propaganda (Answer Commentary)

1517 May Day Riots: How do historians know what happened? (Answer Commentary)