Robert Seymour

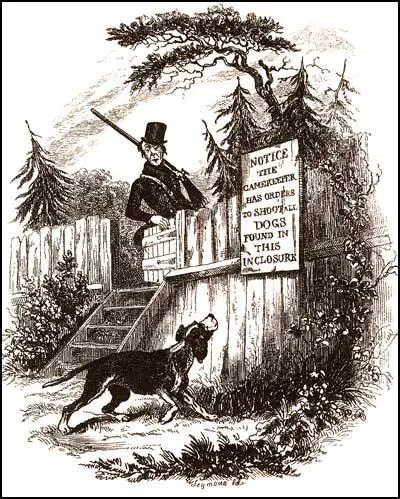

Robert Seymour was born in 1800. He became an illustrator who specialised in sporting scenes. One contemporary noted that he was "the most varied and the most prolific" caricaturist of his day.

In 1835 Chapman and Hall published a successful collection of his illustrations, Squib Annual of Poetry, Politics, and Personalities . The following year, Seymour suggested to William Hall, that he should publish in shilling monthly parts a record of the exploits of a group of Cockney sportsman.

Valerie Browne Lester, the author of Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens (2004), has pointed out: "Robert Seymour needed an author to write up each picture, that is, to provide text to support the narrative contained within the image. This was a common practice, and one in which author was subordinate to artist." William Hall approached Charles Whitehead to provide the words. He had just been appointed as editor of the Library of Fiction and was to busy to take up the offer. Whitehead suggested he should approach Charles Dickens, the author of the highly successful, Sketches by Boz , to become the writer on the project.

Hall offered Dickens £14 for each monthly episode and added that the fee might rise if the series did well. John R. Harvey, the author of Victorian Novelists and their Illustrators (1970), has argued: "Dickens, however, had no intention of writing up anyone else's pictures. When the Seymour plan was put to him, he insisted that he should write his own story and Seymour should illustrate that." Dickens already had an idea for a comic character, Samuel Pickwick, a rich, retired businessman with a taste for good food and a tendency to drink too much. He was based on Moses Pickwick, a coach proprietor from Bath, a man whose coaches he used while working as a journalist. The first number of The Pickwick Papers appeared in March 1836. It came in green wrappers, with 32 pages of print material and 4 engravings, and priced at one shilling.

On the 18th April 1836 Charles Dickens had a meeting with Robert Seymour. According to Peter Ackroyd: "Dickens asserted his proprietor rights over their venture by suggesting that Seymour alter one of his illustrations - a task which Seymour, no doubt against his wishes, carried out... Two days later, Seymour went into the summer-house of his garden in Islington, set up his gun with a string on its trigger, and shot himself through the head. He was, like many illustrators, a melancholy and some ways thwarted man. It has been suggested that Dickens's request to change the illustration was one of the causes of his suicide, but this is most unlikely. Seymour was used to the imperatives of professional life, and it seems that it was essentially anxiety and overwork which eventually killed him."

Primary Sources

(1) Peter Ackroyd , Dickens (1990)

Dickens asserted his proprietor rights over their venture by suggesting that Seymour alter one of his illustrations - a task which Seymour, no doubt against his wishes, carried out... Two days later, Seymour went into the summer-house of his garden in Islington, set up his gun with a string on its trigger, and shot himself through the head. He was, like many illustrators, a melancholy and some ways thwarted man. It has been suggested that Dickens's request to change the illustration was one of the causes of his suicide, but this is most unlikely. Seymour was used to the imperatives of professional life, and it seems that it was essentially anxiety and overwork which eventually killed him.

(2) Robert L. Patten, Charles Dickens and his Publishers (1978)

In 1835 Chapman and Hall issued The Squib Annual, a glossy book for the Christmas trade illustrated by the popular Robert Seymour, political caricaturist and humorous illustrator. In the course of discussion about that book, Seymour broached the idea of drawing plates for a series of cockney sporting scenes, to be issued with accompanying letterpress written to order. Accepting the suggestion, Edward Chapman urged that the plates come out monthly. Seymour agreed, and Chapman and Hall then attempted, without success, to find someone to compose the text. The commission was hardly a flattering one. While comic plates with letterpress were eminently commercial in the 1830s, credit and cash most often went to the illustrator, not the author, who usually took his direction from plates already designed.