Hablot Knight Browne

Hablot Knight Browne, the ninth son of William Loder Browne (1771–1855), a merchant, and his wife, Katherine Hunter Browne (1774–1856), was born in Lower Kennington Lane, London, in June 1815 and baptized on 21st December 1815 at St Mary's Church in Lambeth.

In 1822, when Browne was seven years old, his father fleed to the United States, taking embezzled trust funds with him. To raise her children she relied to a great extent on the kindness of relatives and friends. His uncle arranged for him to attend a boarding-school in Botesdale, Suffolk, where the headmaster, William Haddock, was the first to encourage his artistic talent.

Browne was apprenticed to the engravers William and Edward Finden. At the age of seventeen Browne won the silver medal from the Society of Arts for the best illustration of a historical subject. After leaving his apprenticeship early, Browne established a studio at Furnival's Inn with fellow artist, Robert Young.

In early 1836 Browne was asked by William Hall to illustrate his new monthly magazine, Library of Fiction ,. One of these articles was written by Charles Dickens. At the time, Dickens's was writing The Pickwick Papers. When his illustrator, Robert Seymour, committed suicide on 20th April, 1836, he suggested that Browne should continue with the work. As Browne's biographer, Robert L. Patten, has pointed out: "Dickens recommended Browne for the position. Though the author was an exacting taskmaster, Browne supplied everything Dickens needed in an illustrator. He was a skilled and rapid designer, co-operative, witty, and self-effacing."

John R. Harvey, the author of Victorian Novelists and their Illustrators (1970) has argued: "Hablot Knight Browne, was younger than Dickens, little-known, and pliable; and the collaboration was harmonious and happy." Andrew Sanders has pointed out that Browne was far less of an individualist than George Cruikshank who had worked with Dickens on Sketches by Boz (1836) and Oliver Twist (1837): "He was also much more in awe of Dickens. It is easy enough to denigrate Browne's talent as an artist, but he proved to be an ideal collaborator with the novelist for a good deal of his career."

Peter Ackroyd, the author of Dickens (1990) has pointed out: "Browne's first work in The Pickwick Papers is not very distinguished, and at times somewhat clumsy, but he rapidly and steadily improved so that by the sixth number he had evolved a much cleaner and more detailed style... Dickens understood very well the importance of visual aids both in the understanding, and in the reception of his monthly parts."

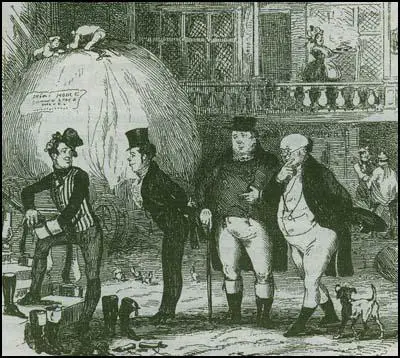

After Dickens's introduced the character of Sam Weller, in the fourth episode of The Pickwick Papers, sales increased dramatically. Weller, the main character's valet, has been described as "a compound of wit, simplicity, quaint humour, and fidelity, who may be regarded as an embodiment of London low life in its most agreeable and entertaining form."

The illustrations by Browne helped to sell Charles Dickens work. It was the etchings which were displayed in the windows of booksellers. Henry Vizetelly, later recorded in his autobiography, Glances Back Through Seventy Years (1893): "Pickwick was then (in 1836) appearing in its green monthly numbers, and no sooner was a new number published than needy admirers flattened their noses against the bookseller's windows, eager to secure a good look at the etchings, and peruse every line of the letterpress that might be exposed to view, frequently reading it aloud to applauding bystanders." By the end of the series it was selling over 40,000 copies a month.

Over the next twenty-three years Browne was Dickens's main illustrator. Using the pseudonym Phiz he produced nearly 740 original and duplicate plates, comprising around 570 steel etchings and approximately 170 wrappers and illustrations engraved into boxwood, plus preliminary designs for 866 wood-engravings. This included, The Pickwick Papers (1836–7), Nicholas Nickleby (1838–9), The Old Curiosity Shop (1840–41), Barnaby Rudge (1841), Martin Chuzzlewit (1843–4) and Dombey and Son (1846–8).

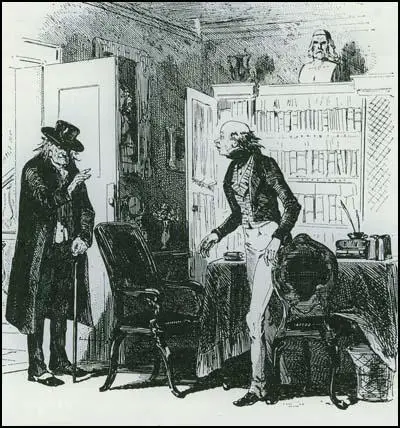

Charles Dickens was about to begin writing David Copperfield in 1849. The novel was originally brought out under the title, The Personal History, Adventures, Experiences, and Observations of David Copperfield the Younger, of Blunderstone Rookery . Browne once again did the illustrations. Valerie Browne Lester has pointed out: "If Copperfield were indeed autobiographical, Phiz was uncannily able to enter into the spirit of Dickens's real memories. He managed to capture Micawber's grandiose and improvident nature - based on Dickens's own father... Phiz seems to be literally under Dickens's skin." Dickens was very pleased with the result and not since The Pickwick Papers had he been so openly appreciative of Browne's efforts.

In November 1851 Dickens began writing a novel which dealt with the condition of England. He found it a difficult story to write and told his friend, Angela Burdett Coutts: "I have been so busy, leading up to the great turning idea of the Bleak House story, that I have lived this last week or ten days in a perpetual scald and boil." Dickens gave Browne, a clear outline of the drawings he wanted for the story. Valerie Browne Lester , the author of Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens (2004): "Dickens was filled with righteous anger against the labyrinthine wranglings of the law courts, and in Bleak House he railed against a society that so thoroughly exploited its people. With Phiz (Browne) by his side, he took on the forces of chaos and darkness."

Bleak House was published in twenty parts by Bradbury and Evans. Dickens's biographer, Claire Tomalin, argues that it has the most powerful beginning of all his novels: "Dickens... rolls out the dark, dirty English earth and sky to set the theme of the book. It will take on the worse aspects of the legal system - its inhumanity, sloth, corruption and obstruction - as a basis for a larger matter, the bad governance of society as a whole; and it will show the physical sickness of London - its toxic water, rotten housing, bursting graveyards and festering sewerage - as part of the effects of that bad governance. There will be almost none of the high-spirited comedy of the early novels."

Several critics made reference to the "dark" illustrations by Browne. One observer pointed out that the drawings "perfectly convey an atmosphere in which evil institutions dominate the lives of the powerless." John R. Harvey, the author of Victorian Novelists and their Illustrators (1970) has argued: "Browne's small fugitive figures reflect.... the novel's general intimation of the pitiable helplessness and isolation of hounded human beings." Jane Rabb Cohen supports this view in her book, Dickens and His Principal Illustrators (1980): "The insignificance of the characters in the artist's plates sensitively reflects their insignificance in the author's narrative, which depicts a society whose institutions dwarf, isolate, and too often destroy members."

In 1855 Charles Dickens began planning his next novel. He decided to write about his experiences of visiting his father, John Dickens, in Marshalsea Prison in Southwark. Dickens, who had given Hablot Knight Browne a "somewhat freer rein in the two preceding novels, he reverted to controlling minute details of the illustrations". On 6th December, 1856 Dickens wrote to Browne: "Don't have Lord Decimus's hand put out, because that looks condescending; and I want him to be upright, stiff, unmixable with mere mortality. Mrs Plornish is too old, and Cavaletto a little bit too furious and wanting in stealthiness."

On 10th February, 1857, Dickens wrote again to his illustrator: "In the dinner scene, it is highly important that Mr. Dorrit should not be too comic. He is too comic now. He is described in the text as shedding tears and what he imperatively wants, is an expression doing less violence in the reader's mind to what is going to happen to him, and much more in accordance with that serious end which is so close before him. Pray do not neglect this change."

Jane Rabb Cohen has argued that Browne's illustrations for the novel were disappointing: "Browne's greatest problem was that by now Dickens usurped his very function. The author had always written unusually pictorial prose. In Little Dorrit his writing became so graphically suggestive yet selective that it needed little visual help."

G. K. Chesterton has suggested that: "No other illustrator ever created the true Dickens characters with the precise and correct quantum of exaggeration. No other illustrator ever breathed the true Dickens atmosphere, in which clerks are clerks and yet at the same time elves." Robert L. Patten has argued: "Browne possessed a talent of real originality, sensitivity, and liveliness, which unfolds with remarkable rapidity and brilliance in the early novels of Dickens.... While the early Dickens plates exhibit youthful buoyancy, inexperience, and a delight in portraying rumbustious crowds, Browne's art, nurtured in the Hogarthian tradition of verbal and visual satire, developed and deepened in time."

The author of Victorian Novelists and their Illustrators (1970) has argued: "He (Browne) possessed a talent of real originality, sensitivity, and liveliness, which unfolds with remarkable rapidity and brilliance in the illustrations for the early novels of Dickens. But there was a frailty in the talent. He produced his best work very early in his career, and having done so, he did not go on, as many artists do, to produce an impressive second-best for his remaining years: he went into a steady decline."

The first episode of A Tale of Two Cities appeared in All the Year Round on 30th April 1859. It did not have illustrations in this format, but Browne was commissioned to provide the drawings for the twelve monthly parts published by Chapman and Hall. The author of Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens (2004) has pointed out: "Phiz's design for the cover of the monthly parts of A Tale of Two Cities was fairly well received.... The rest of the illustrations for the monthly parts were denounced, the detractors criticising Phiz for not moving with the times. They also claimed that the etchings were hastily executed, that Phiz was ill at ease with period costume, and that the images did not add fire to the fury of revolution."

It was the last time Browne worked with Charles Dickens. Apparently he disapproved of the way Dickens treated his wife and never saw him again after the work was finished. He admitted in a letter to his son that while working on A Tale of Two Cities Dickens was "out of temper, and he squabbled with me amongst others." Valerie Browne Lester has argued: "Dickens's personal revolution mirrored the people's revolution in A Tale of Two Cities. Like a snake sloughing off old skin, he was shedding his past and fighting for a new life. He shed decorum and fell in love; he shed his wife and angrily dismissed those friends who showed her any sympathy; ruthlessly and acrimoniously, he shed his publishers, Bradley and Evans; he shed restraint and plunged headlong into an exhausting but enormously profitable series of readings."

In 1863 Charles Dickens began to develop ideas for his next novel, Our Mutual Friend . He decided against running it in All the Year Around and on 8th September, Dickens agreed that he would produce Our Mutual Friend in twenty-monthly installments for Chapman and Hall. Dickens commissioned Marcus Stone to provide the illustrations. His previous novel, Great Expectations , did not have any illustrations so when Browne heard the news he wrote to Robert Young about the decision: "Marcus is no doubt to do Dickens. I have been a good boy, I believe. The plates in hand are all in good time, so that I do not know what's up, any more than you. Dickens probably thinks a new hand would give his old puppets a fresh look, or perhaps he does not like my illustrating Trollope neck-and-neck with him - though, by Jingo, he need fear no rivalry there! Confound all authors and publishers, say I. There is no pleasing one or the other. I wish I had never had anything to do with the lot."

Charles Dickens had used Browne as his illustrator for almost 30 years. It is believed that Dickens had felt that Browne had not given him the required support when he left his wife, Catherine Dickens. He was also probably upset by Browne's decision to provide illustrations for Once a Week , a periodical published by Bradbury and Evans. Dickens had fallen out with this company after its periodical, Punch Magazine , refused to publish his statement attacking Catherine in June 1858.

Peter Ackroyd has argued that Dickens had not been happy with Browne's illustrations for A Tale of Two Cities: "His work for Dickens had been falling off, and his illustrations for A Tale of Two Cities were woefully sketchy and undramatic. He had also been appearing in many different places, which cannot have helped him concentrate upon his Dickensian contributions. The really important fact remains, however, that the particular symbiotic relationship between writer and artist had now disappeared; Dickens no longer needed Browne to give visual strength to his imaginative conceptions, and Browne had ceased to develop and enlarge his range in response to Dickens's own progress as an artist. A separation was, in that sense at least, understandable.... Marcus Stone was younger and fresher than Hablot Browne, but by no means so good an artist... Dickens wanted a new look for his first serial novel in seven years... His work was much more contemporary and much more fashionable - more modern."

Browne also worked for the Irish novelist Charles Lever. It has been claimed that he designed nearly 500 etchings and many wood vignettes for seventeen of Lever's titles. Another important client was William Harrison Ainsworth. His popular novels were originally illustrated by George Cruikshank but Browne replaced him in 1844. Other authors he worked with included Frances Trollope, James Grant, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Edward Bulwer-Lytton, Theodore Hook, Sheridan Le Fanu, Frank Smedley, Robert Smith Surtees and Anthony Trollope. He also provided over 60 illustrations for Punch Magazine.

Hablot Knight Browne died at his home at 8 Clarendon Villas, Hove, on 8th July 1882 after suffering a stroke and was buried in the Lewes Road Extra-mural Cemetery in Brighton.

Primary Sources

(1) John R. Harvey, Victorian Novelists and their Illustrators (1970)

H . K. Browne, was younger than Dickens, little-known, and pliable; and the collaboration was harmonious and happy. ... He possessed a talent of real originality, sensitivity, and liveliness, which unfolds with remarkable rapidity and brilliance in the illustrations for the early novels of Dickens. But there was a frailty in the talent. He produced his best work very early in his career, and having done so, he did not go on, as many artists do, to produce an impressive second-best for his remaining years: he went into a steady decline.

(2) Valerie Browne Lester, Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens (2004)

Phiz's design for the cover of the monthly parts of A Tale of Two Cities was fairly well received.... The rest of the illustrations for the monthly parts were denounced, the detractors criticising Phiz for not moving with the times. They also claimed that the etchings were hastily executed, that Phiz was ill at ease with period costume, and that the images did not add fire to the fury of revolution.

(3) Hablot Knight Browne , letter to Robert Young (1863)

Marcus is no doubt to do Dickens. I have been a good boy, I believe. The plates in hand are all in good time, so that I do not know what's up, any more than you. Dickens probably thinks a new hand would give his old puppets a fresh look, or perhaps he does not like my illustrating Trollope neck-and-neck with him - though, by Jingo, he need fear no rivalry there! Confound all authors and publishers, say I. There is no pleasing one or the other. I wish I had never had anything to do with the lot.

(4) Peter Ackroyd, Dickens (1990)

His (Hablot Knight Browne) work for Dickens had been falling off, and his illustrations for A Tale of Two Cities were woefully sketchy and undramatic. He had also been appearing in many different places, which cannot have helped him concentrate upon his Dickensian contributions. The really important fact remains, however, that the particular symbiotic relationship between writer and artist had now disappeared; Dickens no longer needed Browne to give visual strength to his imaginative conceptions, and Browne had ceased to develop and enlarge his range in response to Dickens's own progress as an artist. A separation was, in that sense at least, understandable.... Marcus Stone was younger and fresher than Hablot Browne, but by no means so good an artist... Dickens wanted a new look for his first serial novel in seven years... His work was much more contemporary and much more fashionable - more modern.